Artists as Messiahs: PETER FEND

|CLAIRE KORON ELAT

In today’s media landscape, a book review is often a slap on the back. A handshake among colleagues that says, “well done.” But we have never been afraid to offer critique when critique is due. In our print section Berlin Reviews, we’ve always tried to take the propositions of a book seriously and push them to their extremes.

Archive Berlin Review from our issue #43

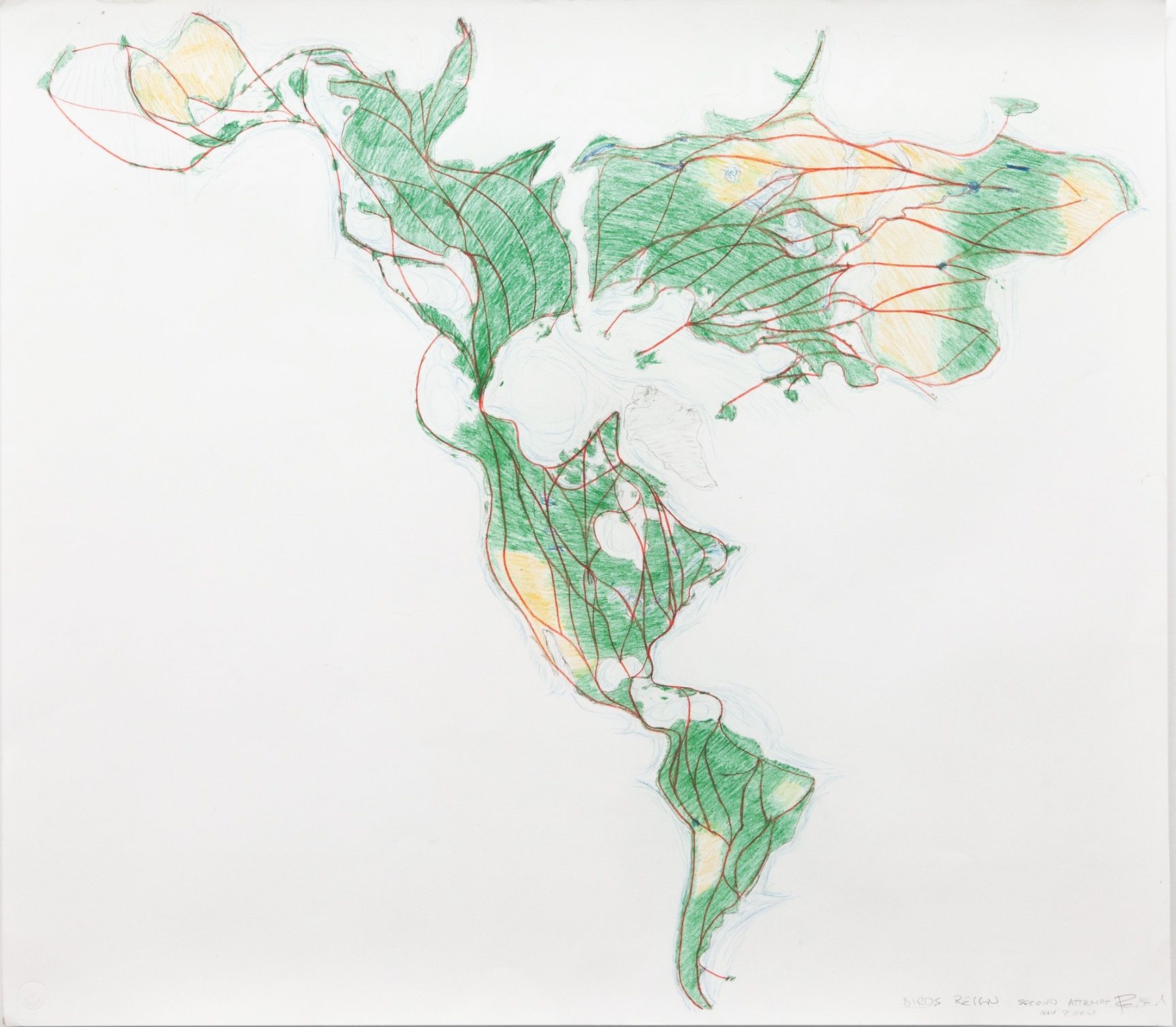

Artist Peter Fend’s monograph Africa-Arctic Flyway Physiocratic States (2022) opens with a boding question: “What if art holds solutions to the ecological crises of our time?” Fend attempts to prove this hypothetical in the documentation of his artworks and projects, which date back to the 1970s. His quixotic proposition is that politicians should be replaced by architects and artists. As a result, the world would be saved from its ghoulish and collateral future undoing. Though Fend has dedicated his entire practice to the fight against climate change, he “is also an utter failure,” as Daniel Keller concludes in a Texte zur Kunst review of a 2015 show by the artist.

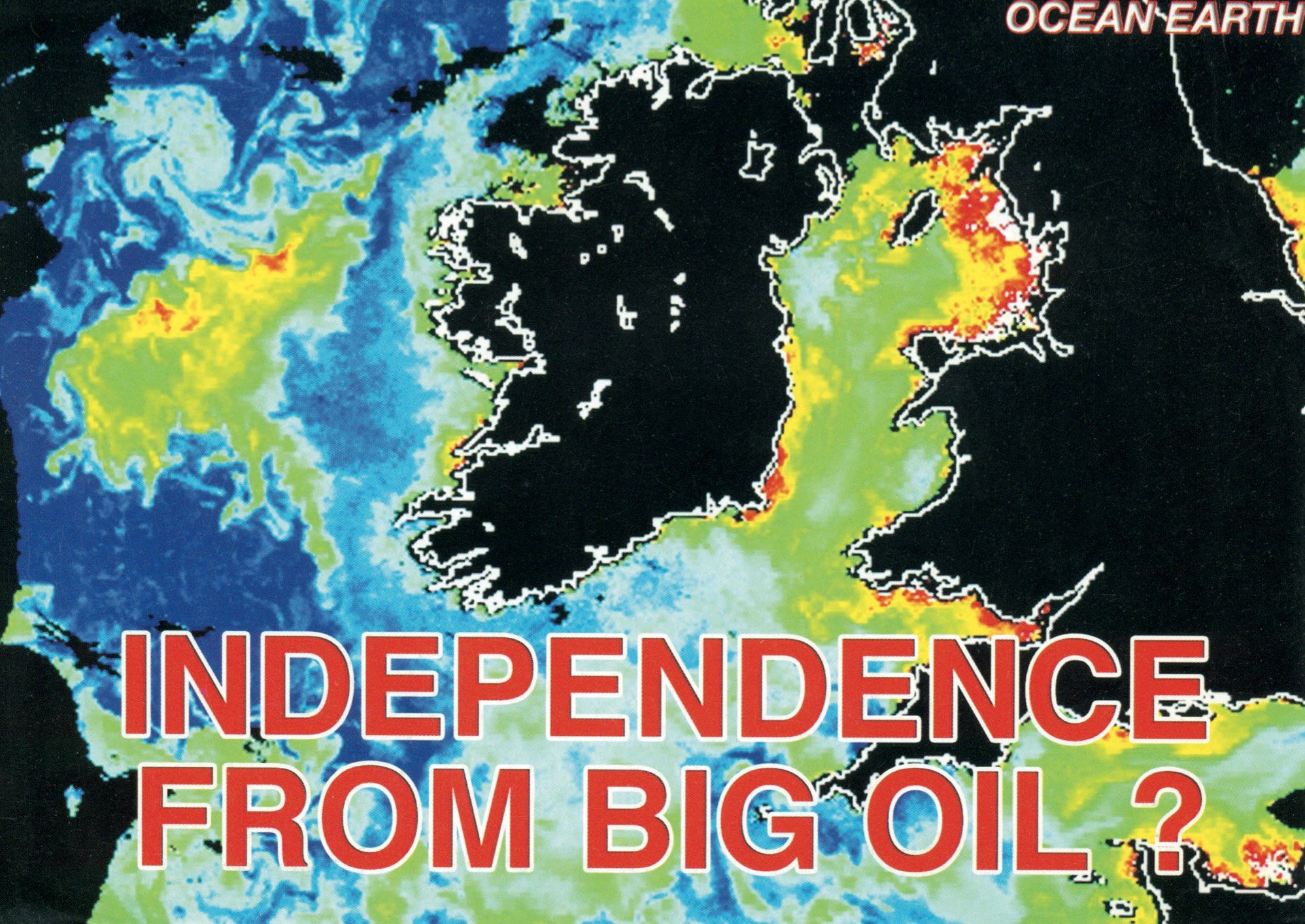

Influenced by Land Art from the 1960s, Fend took part in art movements such as Ocean Earth—which he founded with Jenny Holzer and Richard Prince, among others—a collective whose goal was to find alternative energy sources. Whereas his former colleagues have since gained the art world’s international acclaim, Fend continues to be something of an outsider.

Note that while Fend was already profoundly involved in researching the climate crisis, long before it became as urgent as it is today, he simultaneously also seemed to be prefiguring the current fashion for chain-ganged job titles. Born in 1950 in Ohio, Fend went on to study history and English. At some point in his diverse career, which did not include any training in architecture, he chose to call himself an architect. Similar to the way that individuals (remotely) involved in the creative industry call themselves “curator” today—because they “curate” their Instagrams with 20k followers—Fend decided that there is no need for the proper educational and professional experience; if you really want to, you can be anything.

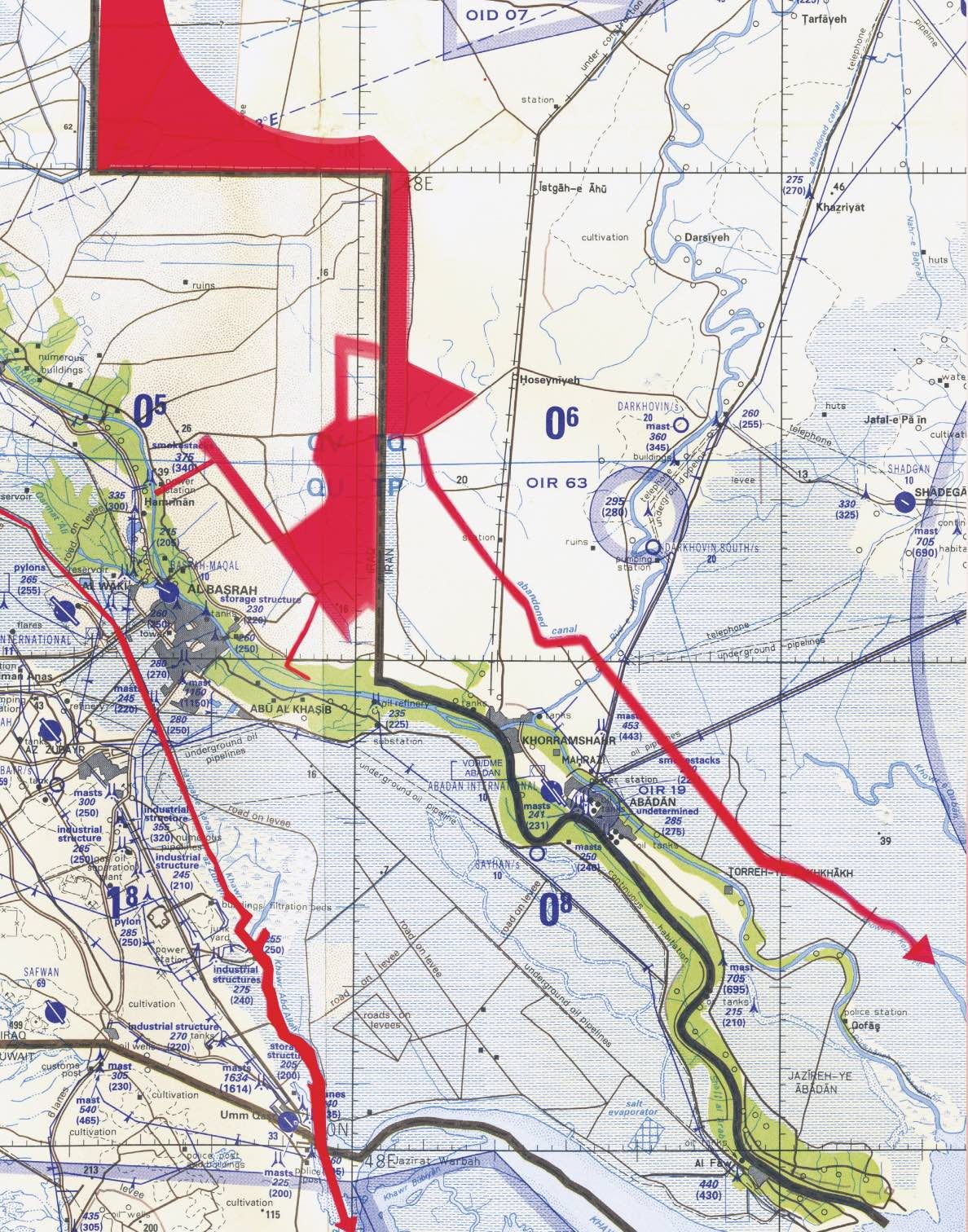

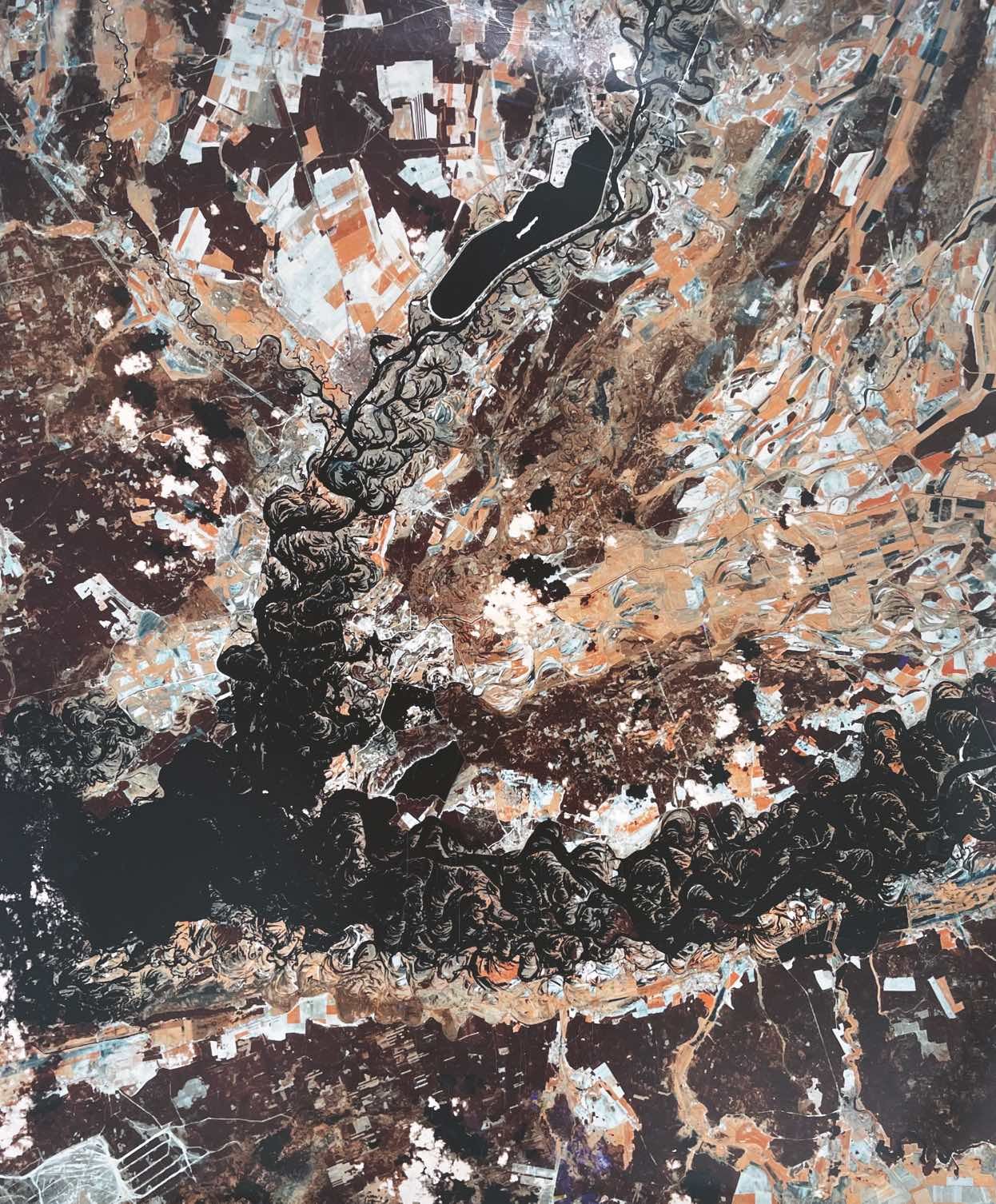

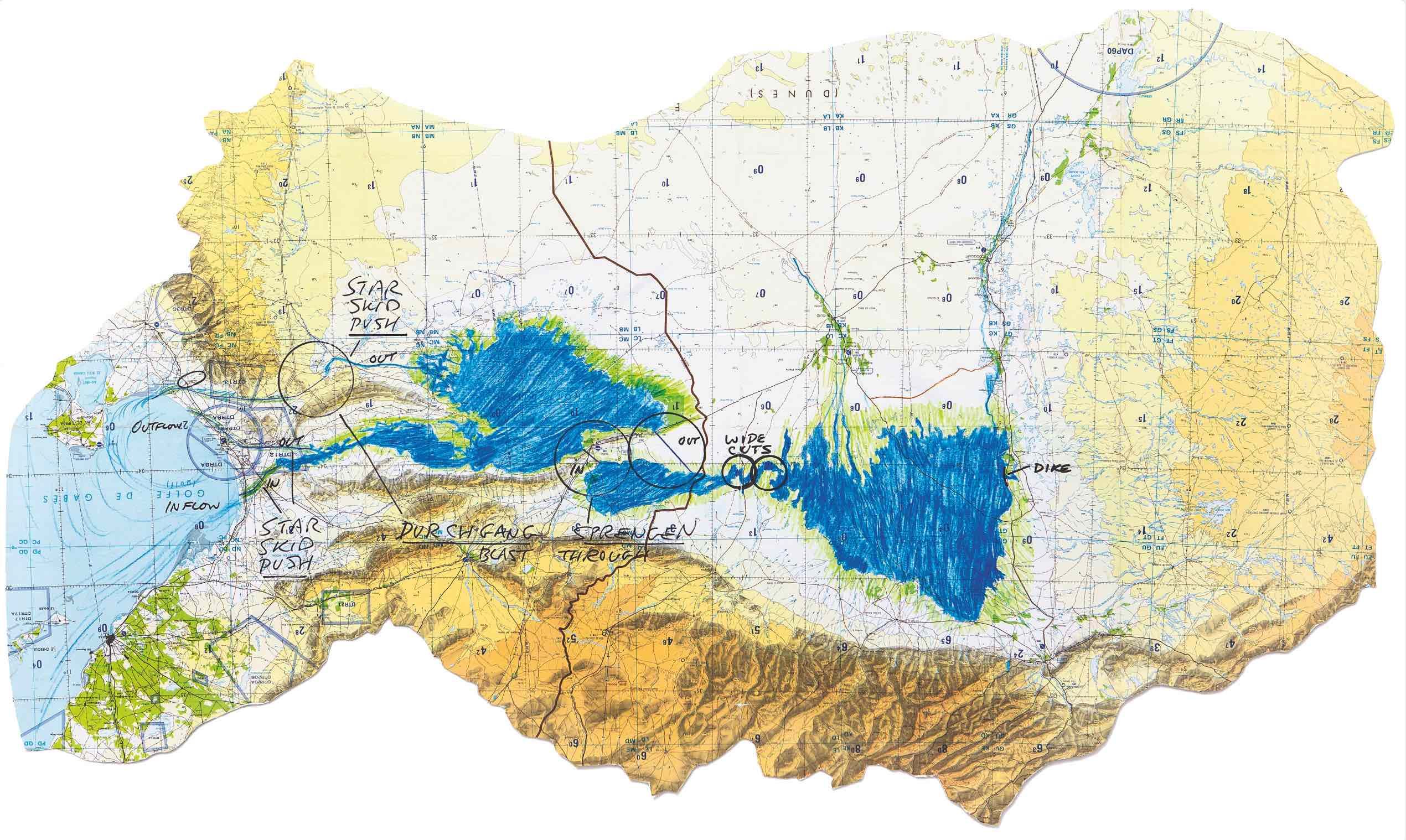

Consisting of various exhibition posters, diagrams, maps, policy proposals, and letters to congress, the book also mentions Fend’s project “Agriculture Ends, Art Takes Over” (1976), in which he insists that humanity should return to pre-domestication land use, a hunter-gatherer lifestyle, and the restoration of pre-Neolithic multitudes of wildlife. Like this suggestion, most of Fend’s ideas are impossible to realize. As Keller writes in his review: “Fend’s ‘to be built’ [the title of an exhibition by the artist in 2015 at Galerie Barbara Weiss] are definitely never going to be built. [His work] is trapped in a state of permanent potentiality. If he weren’t so persistent and earnest about the whole thing, one could almost read what Fend does as an epic troll.”

Why does art, rather than science, hold all solutions to ecological crises? Perhaps because Fend is so wholeheartedly convinced of the power of artists. But then, the artist also believes that he is being investigated by the CIA because his thoughts are so earth-shaking that big economic and business conglomerates intend to impede these notions from ever becoming reality, under any circumstances. Hence, following the artist’s line of thought, science is ruled by politicians and secret agents who are ruled by businesses that will do everything to prevent the world from becoming a better place, because that would come at the cost of their profits. This notion is certainly true in many respects, but, in Fend’s case, it leads to a utopian sphere of delusion that cannot move beyond the realm of potentiality. It is a sphere where artists (and architects) are glorified as messiahs—saviors of humankind—whereas, realistically, human kind might still be doomed, and can be saved only by solutions so radically pragmatic that those who hold power accept and implement them.

Africa-Arctic Flyway – Physiocratic States is published by Sternberg Press (2022).

Credits

- Text: CLAIRE KORON ELAT

Related Content

Artists as Messiahs: PETER FEND

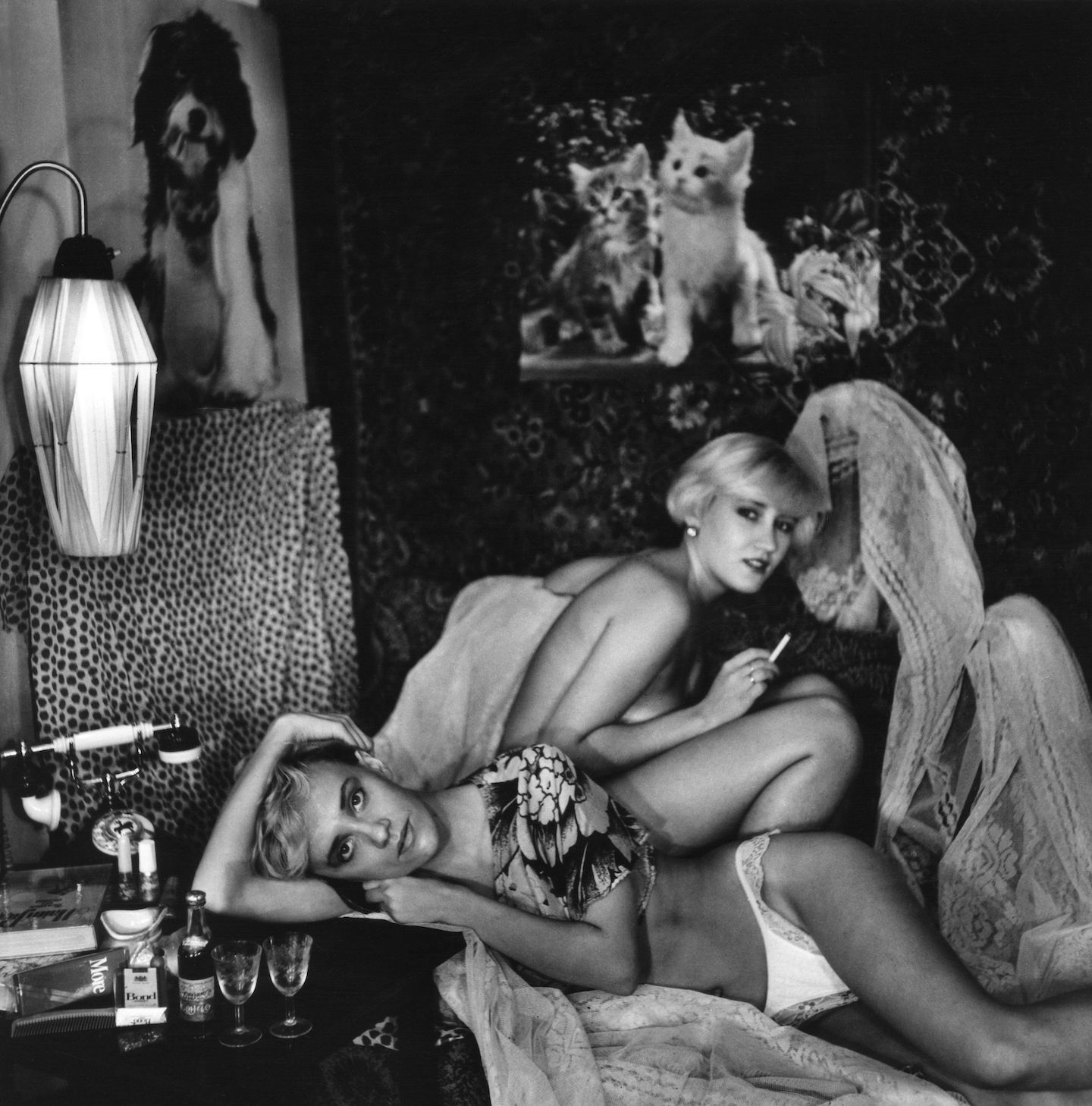

Cobrasnake: Berlin Review

VITALI GELWICH’s Boring Book

An Internet the Size of a Room: Berlin Review

MICHAEL POLLAN Changes His Mind

Ice Cold: Jewelry as Political Embodiments

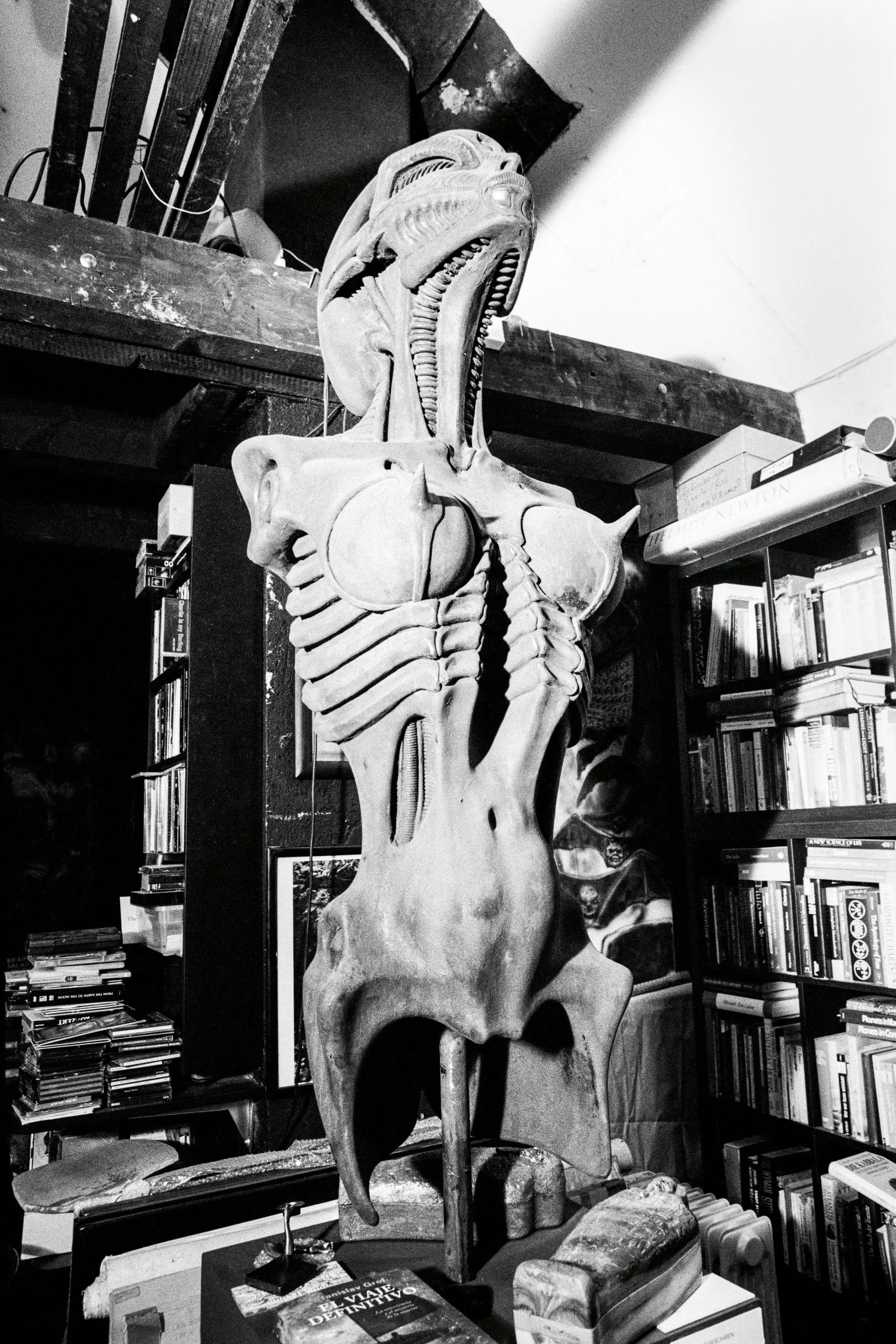

Libidinal Teratology: HR GIGER by CAMILLE VIVIER

Sex and Nothingness: SIBERIAN MODERNISM in the Great Eurasian Steppe