ALVIN BALTROP and the Unofficial History of Cruising on Manhattan’s West Side Piers

|Thom Bettridge

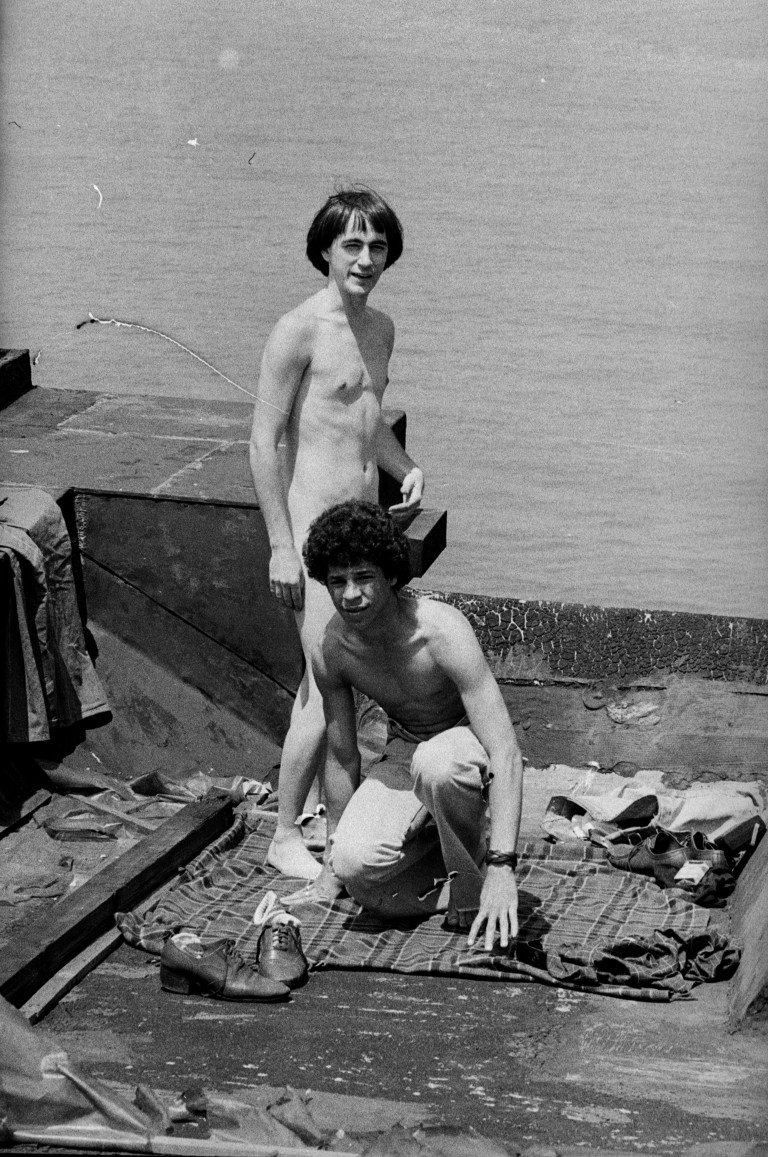

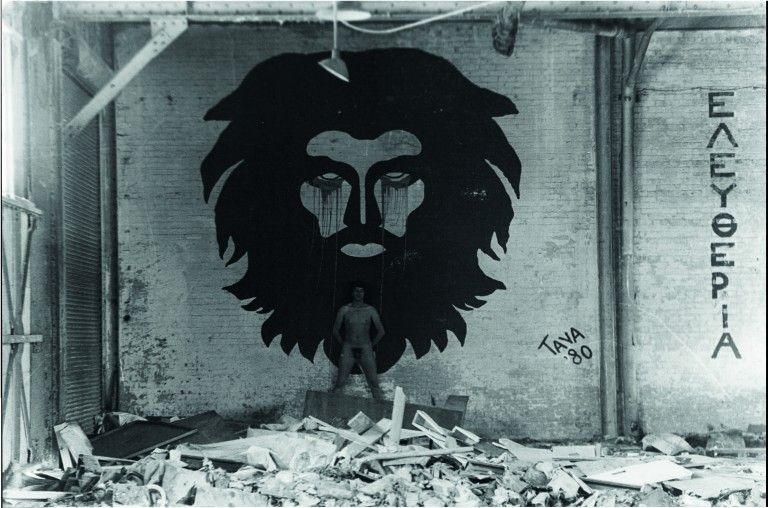

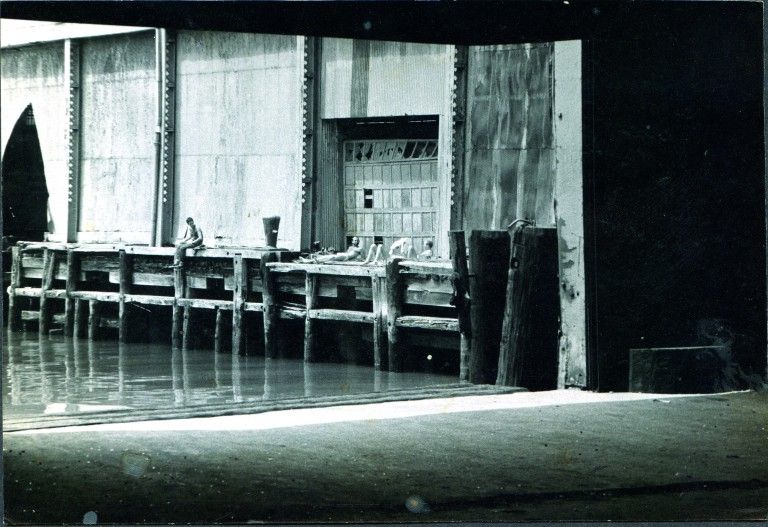

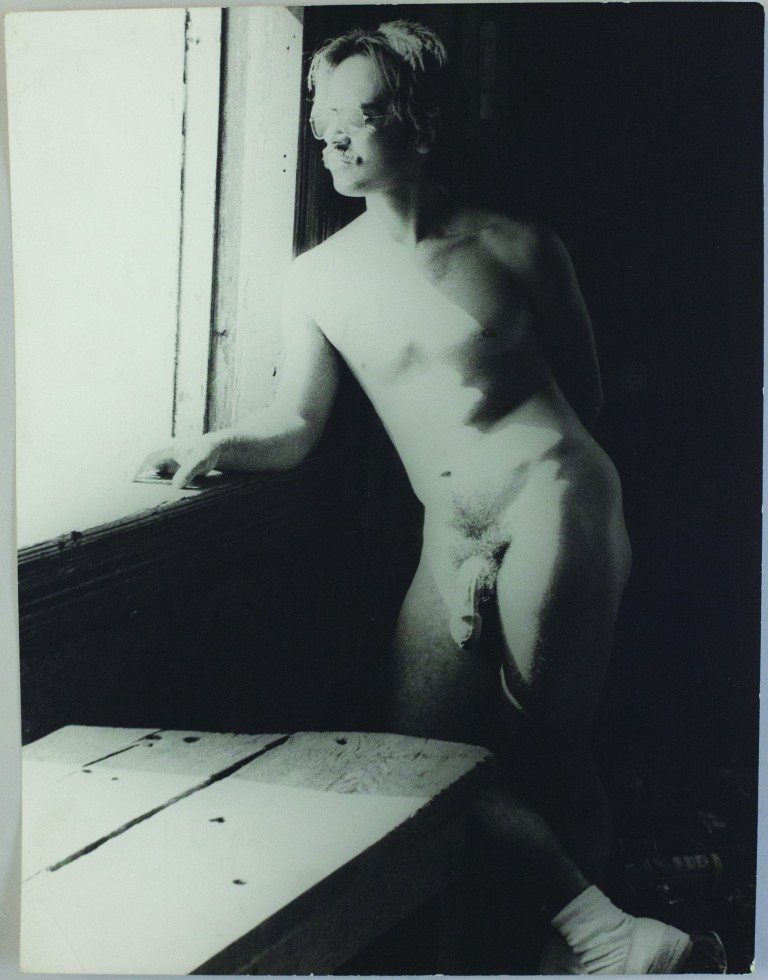

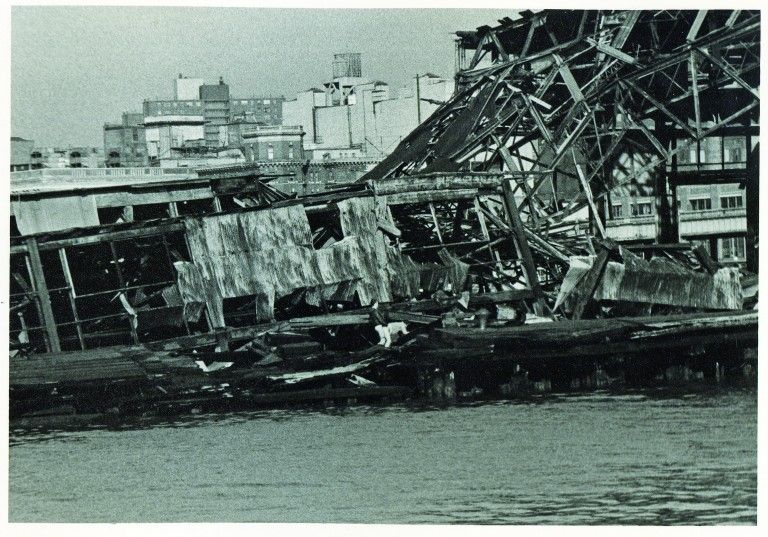

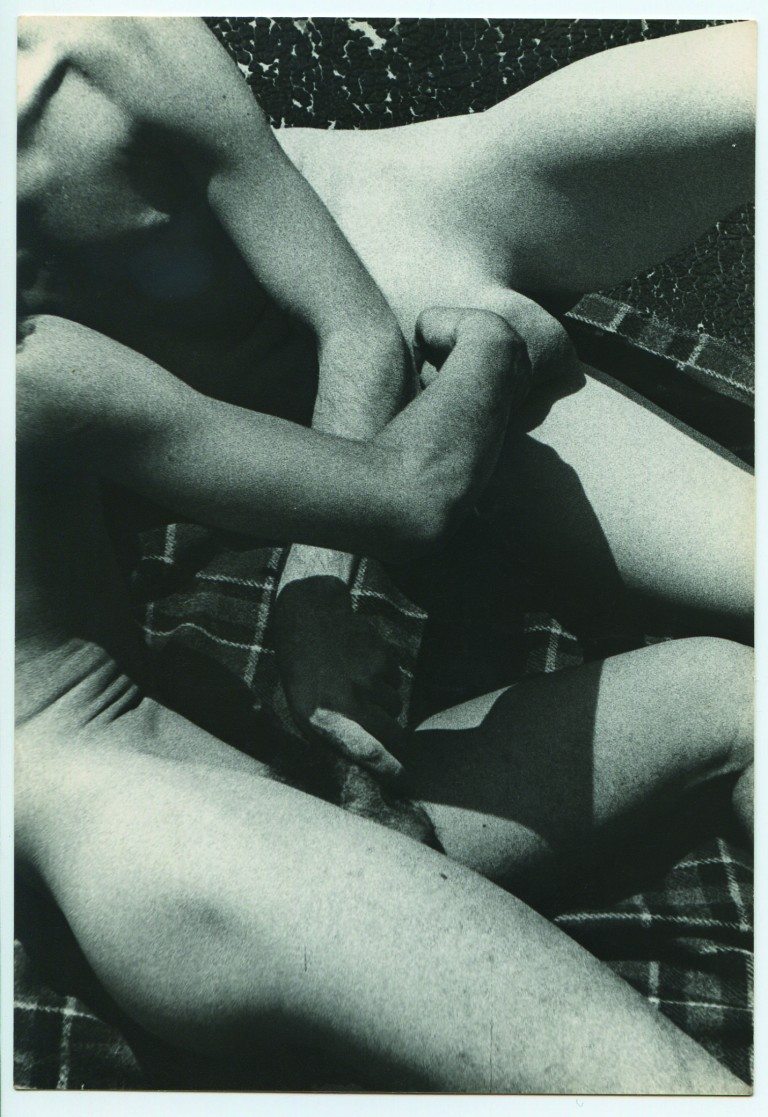

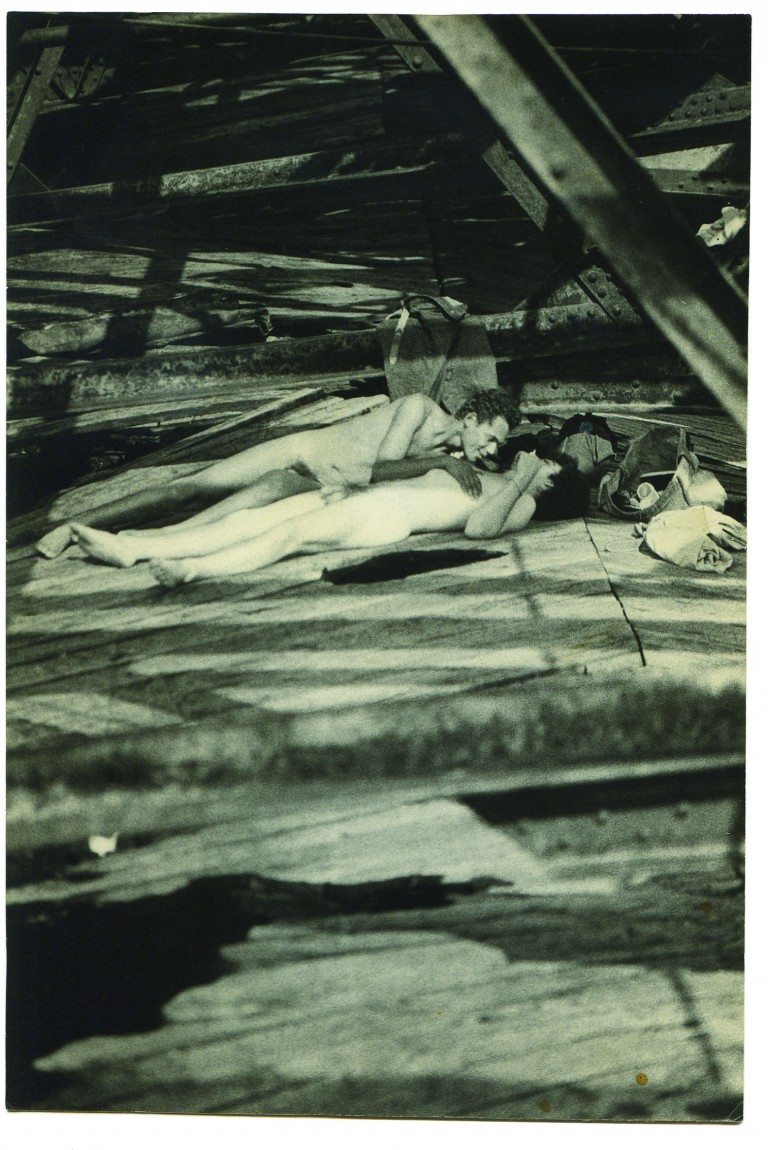

In a grey wash of film-grain, a Hudson River pier folds onto itself like a giant mantis. It is a sprawling pile of softened wood, steel beams, and warped corrugated siding—a man-made wreck so wilted by gravity that it has returned to an almost-nature. As the eye scans across this tangle, it halts at the center of the frame, where a man in a leather jacket with his jeans around his knees takes his lover from behind. It is a scene of illicit promiscuity drenched in a pastoral, 6am silence—much like many of the other pictures in Alvin Baltrop’s The Piers.

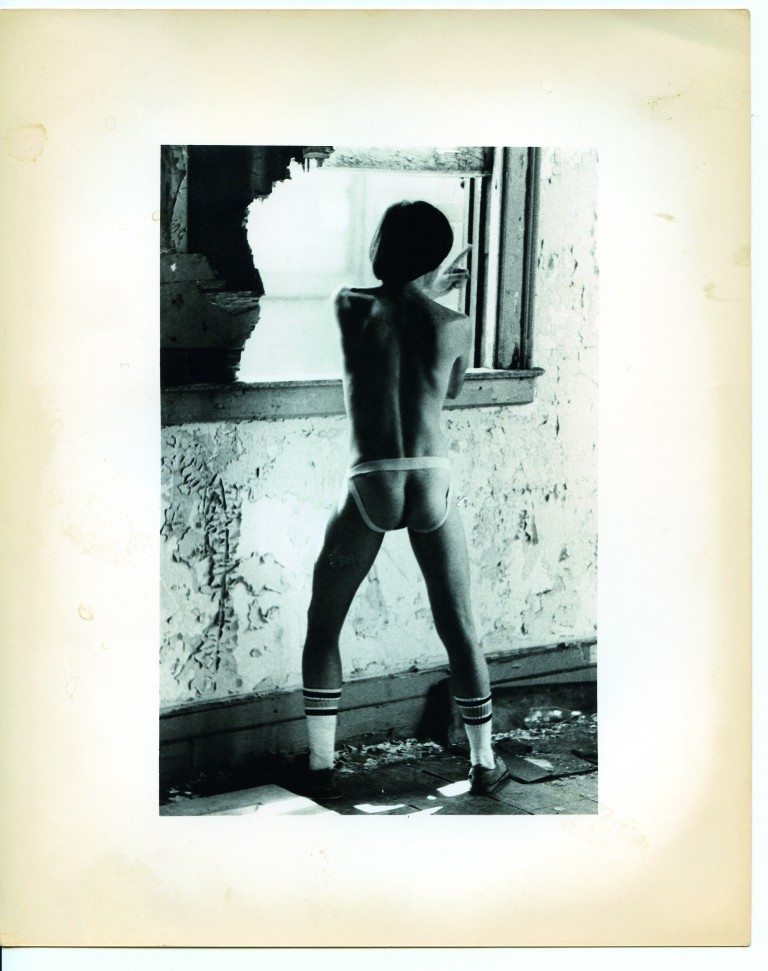

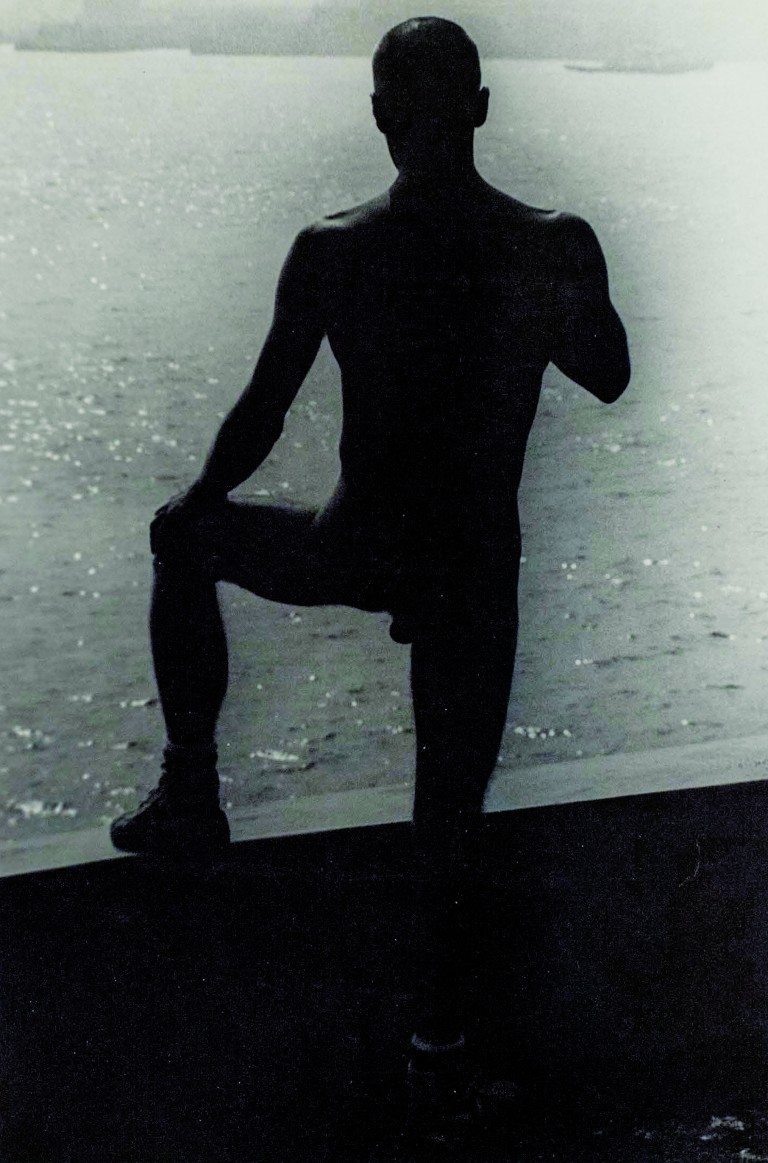

Before Manhattan’s western shoreline was “beautified” in a morose tag-team effort by Michael Bloomberg and Donald Trump, the area was an industrial wasteland. In the 1970s and 80s, the unused piers that dotted this riverside stretch became a haven for gay men who, on account of sodomy laws that banned homosexual intercourse, were forced to play in the fringes. In this semi-protected zone, the vulnerability of a precarious lifestyle was allowed to flourish into true intimacy. Cruisers and hustlers sunbathed on the piers with the grace of ancient greek bathhouse-goers. It was a space that afforded leisure, chance encounters, and anonymous sex.

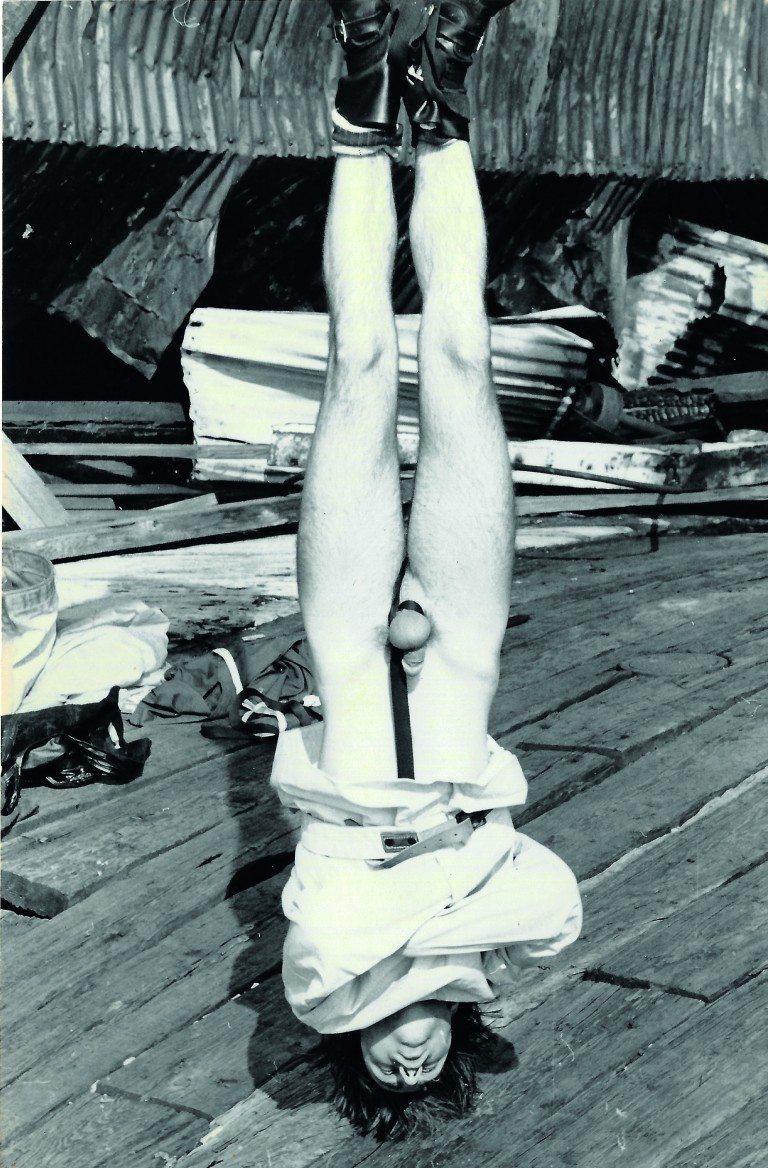

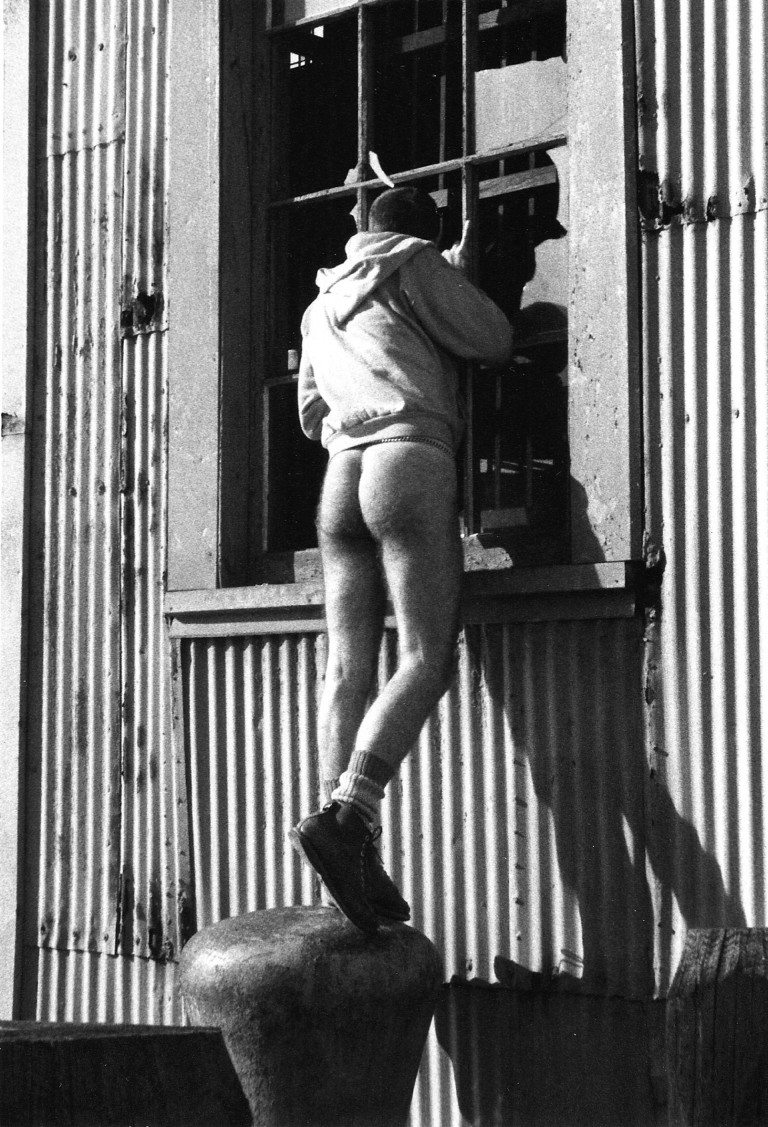

The piers were a place for petty criminals and artists without a stage. The African-American photographer Alvin Baltrop, who captured this scene in black-and-white, falls into the latter category. A Bronx-born veteran and taxi driver, Baltrop did not only photograph the men from the pier, he did so hanging from the rusty warehouse ceiling in a make-shift harness. And they let him, because he was one of them.

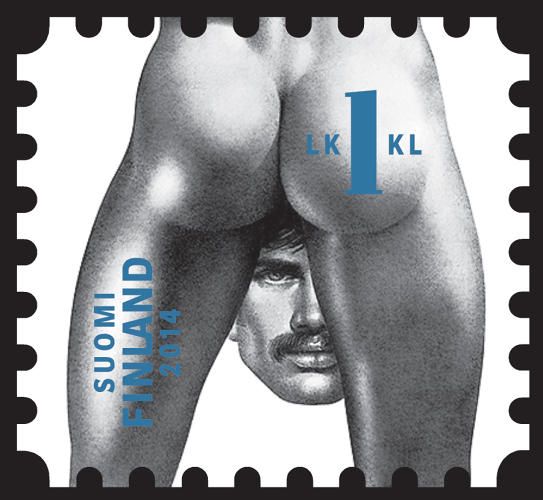

Floating in history behind the Stonewall Riots and the impending AIDS epidemic, Baltrop’s photographs offer a tender and escapist vision laced with the violence of oppression. They are a clear representation of what philosopher (and rumored cruiser) Michel Foucault once described as a “heterotopia”: a space wherein societies can form outside the bounds of normalcy. In this sense, the piers were a counter-proposal for a future that never happened. But more importantly, the world of Baltrop’s images reveal the tenacity of pride in the face of poverty and bigotry. A sunny space near the ocean is a human right. And, as Glenn O’Brien remembers in his forward to TF Editores’s monograph, the piers were like a “poor man’s Fire Island.”

032c’s Thom Bettridge spoke with James Reid, who edited The Piers

What inspired you to begin this project? Was that image of two men fucking in the ruins a eureka moment for you?

In 2010 there was an encyclopaedic group show at the Reina Sofia in Madrid called Mixed Use, Manhattan that filled an entire floor there. It featured works from a whole raft of pioneering artists, photographers, and filmmakers like Danny Lyon, the Bechers, James Welling, David Hammons, Sol LeWitt, and Steve McQueen, all of whose work in the show explored the aesthetic allure and potential of Manhattan in varying ways. There was a lot of great, stand-out work and a lot of larger scale work that grabbed your attention. In one room on one wall were these small 10×8 prints with obvious signs of wear – with fixer stains and torn edges – of derelict old buildings. The pictures were so discrete that you almost passed them right by. It was only when I did a second run through of the show that I gave them a closer look and was amazed as these figures emerged from the mangled buildings in these prints. First just fleeting shadows, torsos struck by a shaft on sunlight. And then it became apparent these figures were naked gay men cruising or – in the case of the image that became the cover of the book – having full sex in the ruins of the West Side piers in New York. They were astonishing images — so raw and powerful. I had never heard of Alvin Baltrop at this point, but these 3 or 4 prints made me want to see everything he’d done.

The subcultures of downtown New York have been mapped so many times. Especially in photography. How did Baltrop’s story feel different to you?

The haunting and visceral quality of Baltrop’s images really stand apart for me, as well as the intimacy. Many of them are just so raw that you think, “Are they really doing that?!” He was fully immersed in the piers scene, to the point where he converted a van so he could sleep in it by the West Side Highway and load and process his films there. And he obviously had the trust of his subjects, so some of the images are just staggering. He had a great eye. The compositions and use of light in the more architectural shots are so strong. I also think this particular scene was so unknown to most outsiders that it was something of a revelation when his images finally came to public attention years later.

Something striking about the book is how it oscillates from moments of totally bucolic sexual freedom and dark snippets of social brutality. Are these types of extremes something that exist today? Or has this huge bandwidth of pleasure-pain mellowed out with time?

At this point in time, I don’t know if they do exist in such an extreme way or on such a big scale. There are of course still scenes and subcultures, but I don’t know of any that represent such contrasts and risks, at least in the Western world. You have things like the dogging scenes in the night in the forests around London, but I don’t think death is ever a risk with that. Saying that, the world is a large place and maybe thirty years from now, someone else’s undiscovered photographic survey will appear and astound us.

Credits

- Interview: Thom Bettridge