Soldier: "Painting is about making the things you love immortal"

|MAX ROSSI

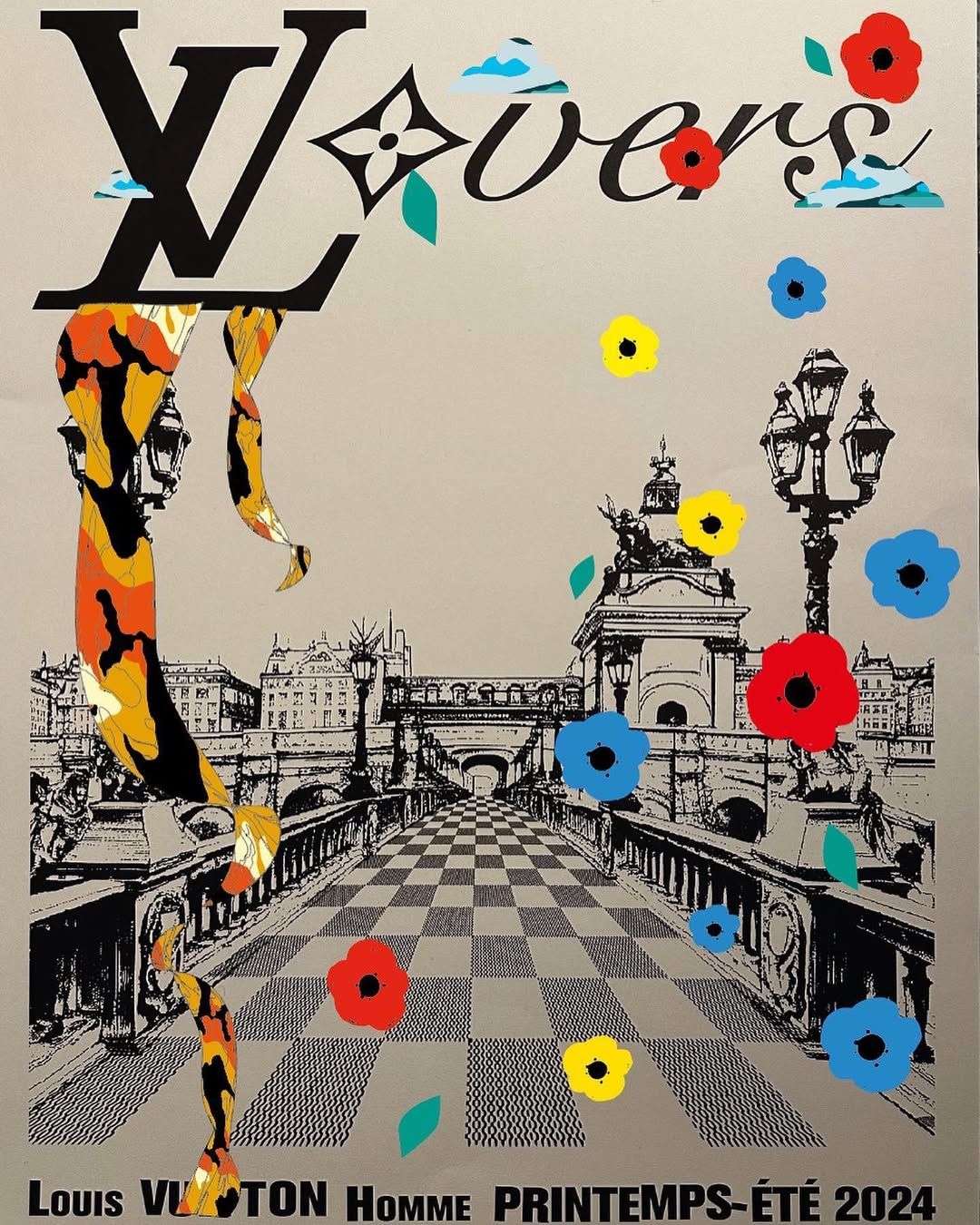

For Nigerian artist Leonard Iheagwam, watching skate tapes and staring at Bible engravings during Sunday service served as early inspiration. Now known professionally as Soldier—a moniker born out of defiance against Nigeria’s military establishment— Iheagwam has since built a complex practice spanning painting, portraiture, sculpture, pop art, and fashion collaborations with Salomon, Louis Vuitton, and Hublot.

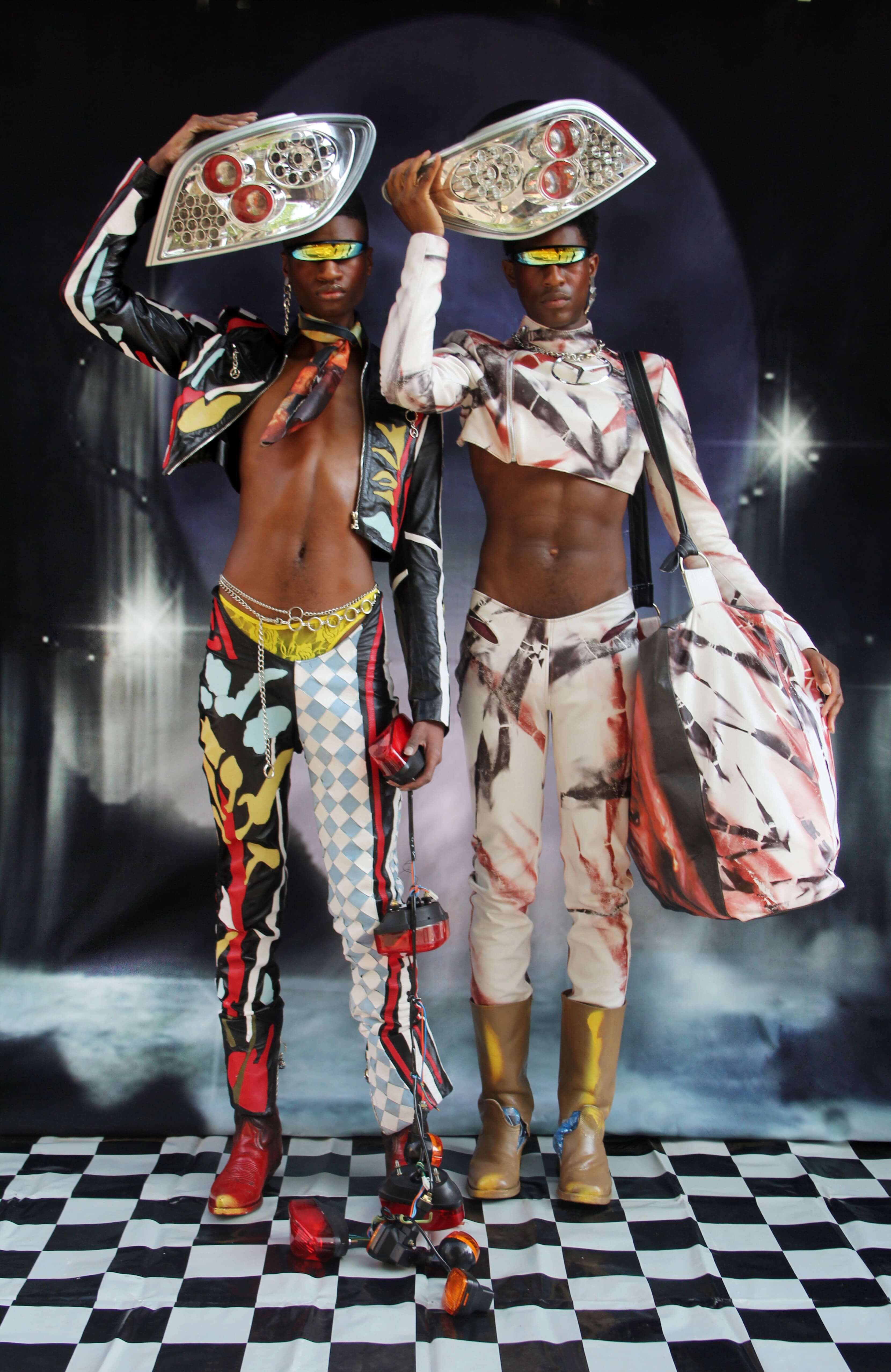

Continuously reshaping his visual language, the multi-hyphenate artist has recently opened the solo show “Black Star” at Kearsey & Gold in London. Featuring a dozen new works, the exhibition imagines a toxic future where humanity survives through tech- woven exoskeletons—yet the pieces remain deeply grounded in his African roots.

After the opening, Soldier spoke with Max Rossi about how to evolve your style without becoming your own cliché, and why his work cannot be reduced to a single meaning.

Artwork for Louis Vuitton

MAX ROSSI: You left Nigeria as a teenager to come to the UK. Why did you move?

SOLDIER: I ran away from home at 16. I was in Lagos, and my dumb ass just decided to bounce, going from house to house, [with] no plan. I don't know what I was thinking. Nigeria's not exactly the safest place either, so I’m honestly just glad I’m alive. [Laughs] But it was because of skateboarding, art, and design. I felt boxed in. My dad’s a reverend, we didn’t come from money—and in Nigeria, there's no middle class. You’re either rich, or you’re really not.

I wanted more for myself. I wanted to travel. I wanted to see Europe, and America. For some reason, I stumbled across skateboarding and it was crazy for me. Back in Nigeria, we didn’t have any skate parks or facilities—it’s a third world country. So, when I ran away from home at 16, I met all my friends and we helped build Wafflesncream, the first skate shop in Lagos, and founded our own brand called Motherlan. Then, I got a scholarship at 19 and came to London. That’s when I moved out properly.

MR: How did you come across skateboarding in the first place? Was it because of online video tapes?

S: Yeah, mostly online. The internet opened up my whole world. I was an internet baby— this was around 2016, when social media was a thing, but not too much of a thing yet. We were at the edge of it. I watched a ton of movies online, and they completely shifted how I saw everything. Then I came across skateboarding and thought, "Yeah, that’s it.” I fell in love.

MR: How did skating inform your artistic practice?

S: Back in the Wafflesncream days, Jonny—the owner—was the one who really introduced us to the idea of community. He showed us that you could just design a T-shirt, throw a graphic on it, and sell it. We even made custom boards with our own designs and sold them with a little markup to raise money for the first skatepark in Lagos. The biggest thing skateboarding taught me was resilience. I’m no pro—I still struggle with a treflip. But for me, it was never just about tricks. It was the culture: the graphics on the decks, all these personalities coming together, breaking boundaries, falling and getting back up. That mindset shaped how I approach my work today. And seeing brands like Supreme collaborate with artists and musicians really opened my eyes to how art can move in different ways.

MR: Do you still skate?

S: When I first got to London, we were hitting the parks hard those first couple years—but mostly, I was just trying to survive. Skateboarding will always be a part of me, but now that my focus is on art and design, it sits in the background.

MR: What was it like growing up as an artist in Nigeria?

S: It was hell. Not fun at all. One of the reasons I left home so early was because if I’d tried to chase what I actually wanted under my family, it would have ended badly. You grow up in a place where you’re supposed to be a doctor or a lawyer—and I’m like, "I want to paint.” When you look at Europe or the US, you hear about people such as Picasso or Dalí and you start to see that art can be an industry. But in Nigeria, it’s not like that. You barely hear those stories. Everyone’s just trying to survive, so the goal is always to do something that brings money. It was tough. Really tough.

Opening of "Black Star" at Kearsey & Gold in London.

MR: Yet, here you are. What do people say now that you've made it as an artist?

S: It’s about proving a point. At first it was, "Oh my God, you’re insane. You’re going to die.” But it worked out. I think if you have something to say, you’ve got to prove it. Obviously, it could have gone the other way; not everyone runs away from home and lands on their feet. But I stayed focused. I treated this like a job from day one. And now I’m making them proud—with art and design. That feels amazing.

MR: How does your African background shape you as an artist?

S: The name Soldier came from growing up in Nigeria, where there’s a lot of civil unrest— military coups, the army taking over. Civilians aren’t even allowed to wear camouflage. I remember having a pair of camo pants, and some soldiers stopped me like, "stop fucking around with that shit.” Then I came to England and realized you could walk into a store, buy camo, and wear it freely. I was young, and I took the name Soldier as a way to claim freedom, rebellion, all of that. It stuck. As for the work, I paint portraits and figurative pieces mostly of people from the Black community—people who look like me, where I’m from. I’ve painted my mum, my dad, my whole extended family. That part of me is always there. Nigeria is in all of it.

MR: What are the main visual elements and themes in your work?

S: I try to stay as honest as possible with myself and to keep learning, never limiting myself to one style or idea. As an artist, if you’ve got something to say, just do it. In the art world, you see a lot of people sticking to the same theme or style for years. But if you look at my work, I think you’ll see freedom of thought and experimentation. I’m always exploring new things, pushing boundaries, and going different places. I don’t want to repeat myself—that shit’s boring.

MR: Is there an expectation of how a Soldier work should look?

S: If there is, I don’t care. Let people think whatever they want. When I make work, I don’t focus on how it will be perceived. It’s about me first. People tell me, "That camera work was sick,” but that was years ago. I’m not doing that anymore. Maybe next I’ll be painting with sticks or something. I don’t worry about controlling how people feel about my work. Yeah, some things I do are recognizable, and sure, it might make good money, but I try not to stay in that lane for too long, so that I don’t get boxed in.

MR: Part of your practice is infused with a religious, quasi-sacred aesthetic, reminiscent of church icons. Why?

S: I grew up in the church, and a big part of my introduction to art were the illustrations and engravings you see in the Bible and religious literature. Even though I didn’t realize it at the time, I was inspired by it. I feel like whenever I paint people, I want to capture personal details but also give it an impersonal take that feels almost magical, like icons on the tinted glass in a Church.

In my last show, “When the Saints Go Marching,” I painted my mother, my dad, siblings, and even some actors I admired growing up. I want these people to live forever through my work. For me, painting is about making loved ones—and the things you love— immortal.

MR: Much of your work doubles as social critique, but can you separate art from politics?

S: You can, but then you’ll turn up with some shit like the Teletubbies. I feel like when you’re making work, you need to say something. The world we’re living in is too crazy to not address. I don’t consider myself overly political, but I can’t make art that doesn’t respond to something. I’m not out here scanning the newspapers every morning for inspiration—I don’t even want to go near that. What I do know is that whatever I absorb as a human being, I end up funneling into my work.

Also, I think the beautiful thing about art is that it lets people latch whatever they want onto it. If others want to inject their own meanings into it, I don’t mind. But you should have fun with it.

MR: Later, you started collaborating with brands like Louis Vuitton and MARNI. Is fashion and commercial work just a way to get your message out or are you exploring something else entirely?

S: I think both. When you make art, you do it in tiers. The highest tier, the painting, is more expensive and harder to get. But you also want regular people to experience your work, which is why I started painting on boards. When I work with fashion brands or create art for them, it’s about spreading the message, but also about giving people different avenues to experience what I do. If I could, I’d make music too. I want people from all walks of life to be able to grab a piece of me. For this exhibition I partnered with Salomon who came in and supported the show and so I feel there’s always an element of fashion influence, whether that be in what I wear or who's involved, in a lot of what I do.

MR: You use military aesthetics, like camouflage, as a critique of authoritarianism and war, but when brands commodify it and turn it into something "cool,” does the message lose weight? How do you balance the risk of your deeper motifs becoming "just fashion?”

S: Like I said, I spend most of my time exploring things. There’s always a message, but it’s not just one—more like ten of them. I like fashion, and yeah, it’s a symbol of consumerism. You can’t deny it; we all consume. You can’t escape culture and human nature. Brands are huge parts of our world, and yeah, they’ve got flaws. But who doesn’t?

MR: Your latest exhibition "Black Star” just debuted at Kearsey & Gold Gallery. What is it about and what does it mean to you?

S: The more I painted, and the more I pushed myself in new directions, the more I realized I was focusing a lot on the past and present. Yet, with everything moving so fast— technology, AI, Neuralink trying to implant chips in people's brains—I couldn't stop thinking about what the future might look like. That’s what this exhibition is about.

I’m trying to reimagine the future and figure out where people who look like me will fit into it. This isn’t Afrofuturism, it’s just my take on the future beyond race. It’s a critique, because I honestly don’t think the future is going to be great or amazing.

MR: Is it dystopian?

S: Very dystopian. The characters are on Earth, but it feels like they’re in space. The sky’s orange, not blue anymore. I read somewhere that every time you use ChatGPT, a forest dies or something like that. We love technology, but there are a lot of consequences, and that's what I try to subtly capture.

MR: Are you drawing from sci-fi or a specific aesthetic?

S: It’s purely my own take. The faces I paint are a mix of people I know. The tech is all my own invention. Sure, I love Star Wars and have read a lot about how the future might look, but this is a blend of my personal influences with a critique.

MR: Why is it called “Black Star?”

S: First, because the characters are Black. But also, when you think of a black star, it’s like an eclipse—something obstructed by another planet, where light doesn’t pass through. For me, that’s a way to insert myself and my identity into the future. I want everyone to do the same, alongside the critique of technology and its consequences—to insert themselves into the story.

Credits

- Text: MAX ROSSI

Related Content

“No Such Thing as History” at Espace Louis Vuitton in Munich

Mathematical Skateboarding with Ishod Wair

Found Futures: Introducing the Mowalola Man

NICHOLAS GHESQUIÈRE and JUERGEN TELLER Bring Us the Future-Archeology of LOUIS VUITTON Autumn-Winter 2016

Dozie Kanu: EVIL

SILBER FREARE for SALOMON Fell Raiser Mid x GR10K – a.k.a. Terrain-Vore