“Slowed and Throwed”: DJ SCREW, Community, and Collage

|Jeffrey Martín

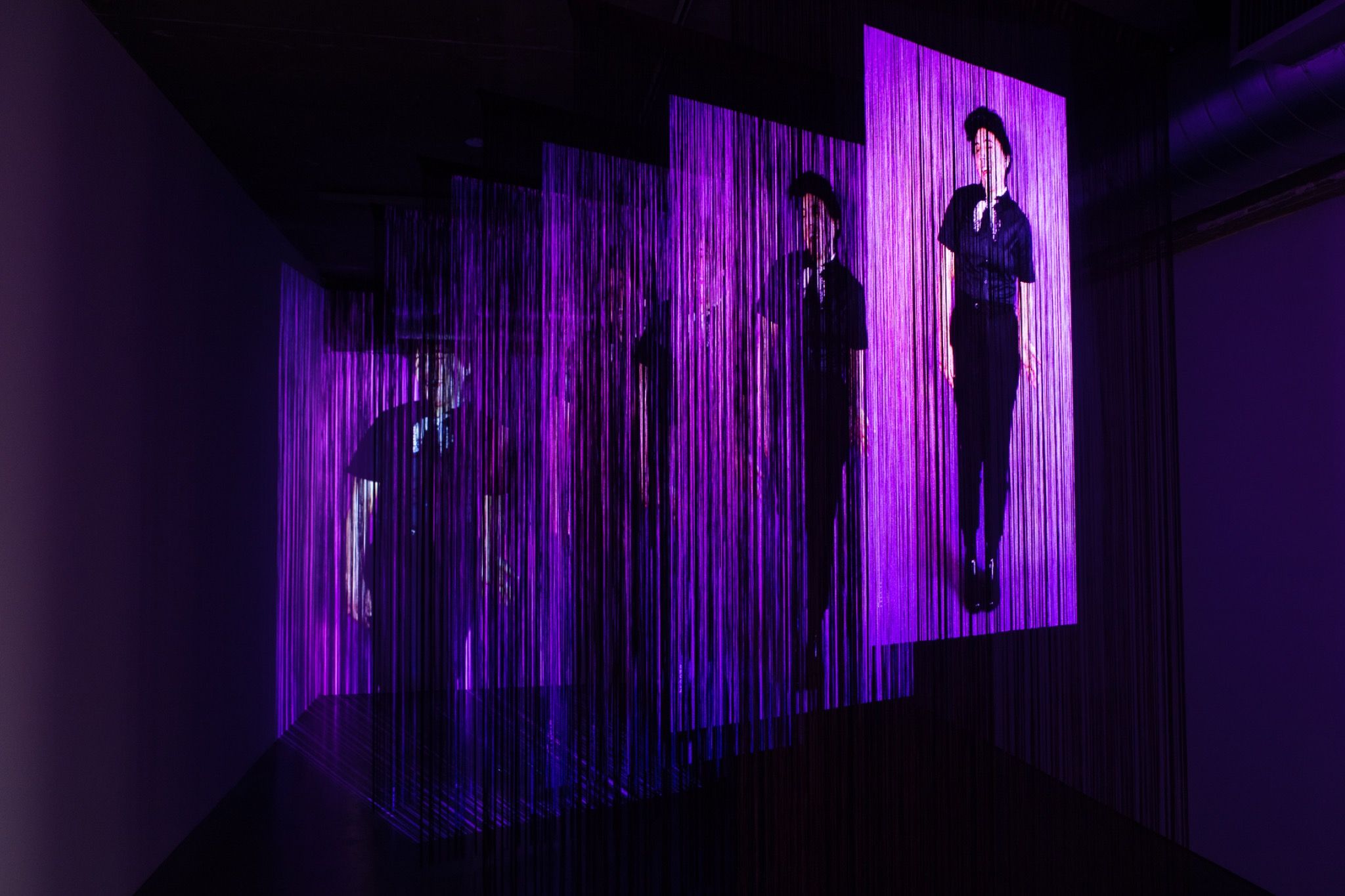

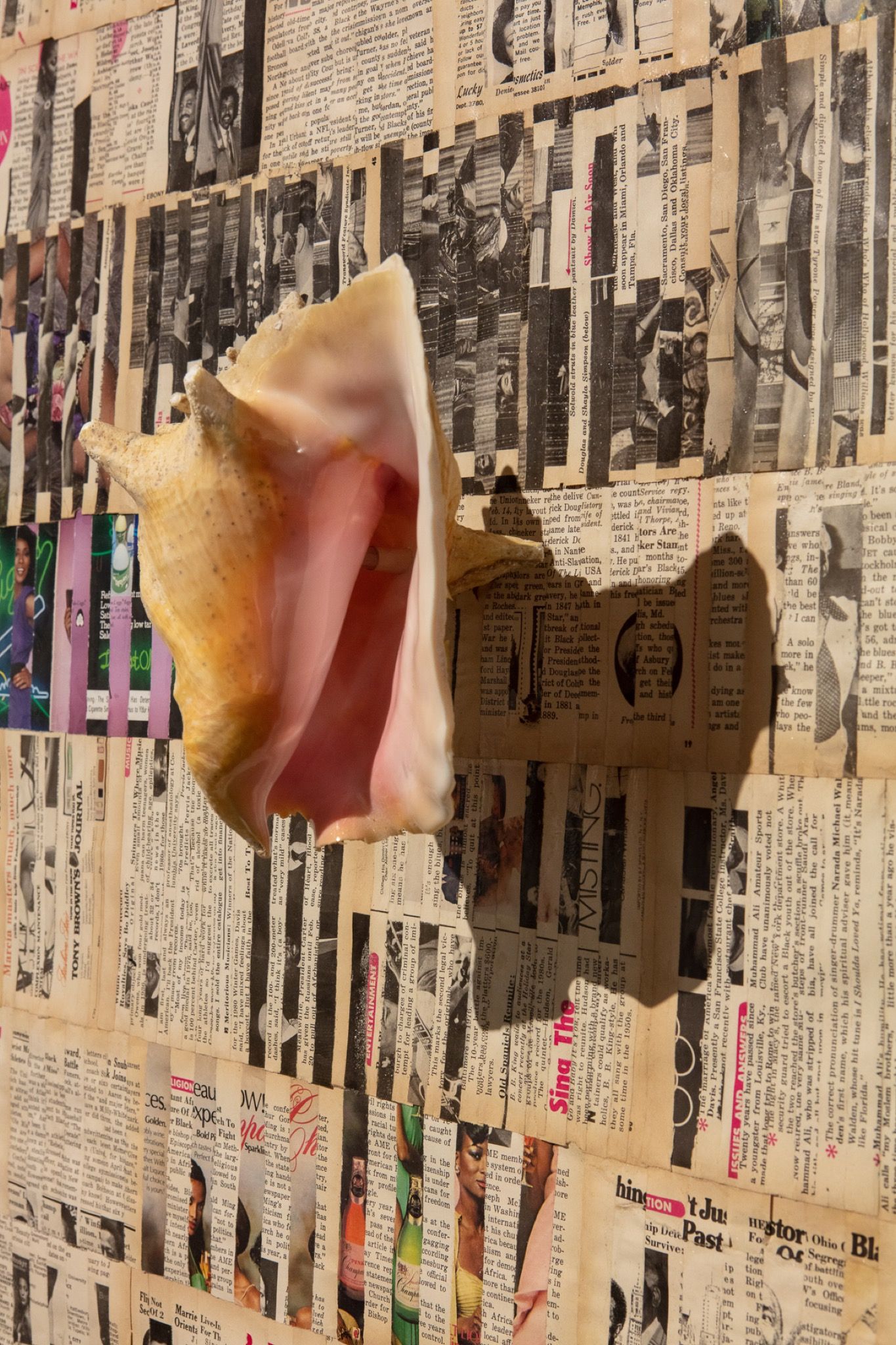

Debuted in March 2020 to staggering crowds, “Slowed and Throwed: Records of the City through Mutated Lenses” – a multi-disciplinary exhibition of archival materials and contemporary artistic responses to the life, work, and impact of the late DJ SCREW – reopens at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston this month following pandemic-related closures. In this two-part digital feature, interviews with exhibition organizers, advisors, and participating artists expand on the DJ SCREW story inspired by the show and published in 032c Issue #38 (Winter 202/2021), where quotes from these conversations accompany imagery and essays exploring the legacy of the Houston musical legend. To read additional texts available only in print, click here.

In this second installment of our “Slowed and Throwed” digital feature, Jeffrey Martín follows up interviews with CAMH curator Patricia Restrepo, Screwed Up Click member ESG, and independent hip hop educator Rocky Rockett – which you can read alongside the author’s introduction HERE – with a conversation between TAY BUTLER and ROBERT HODGE, whose work infused with Screw’s legacy is currently on view in Houston alongside the musician’s archive. The artists discuss the “chopped and screwed” legend’s influence on their respective practice – via the inherent postmodernism of Southern hip hop.

Jeffrey Martín: We can’t really talk about hip hop without chopped and screwed. Y’all as artists took the improvisational techniques from the turntable and kind of applied it to your practice. How did you memorialize DJ Screw’s chopped and screwed method in your material?

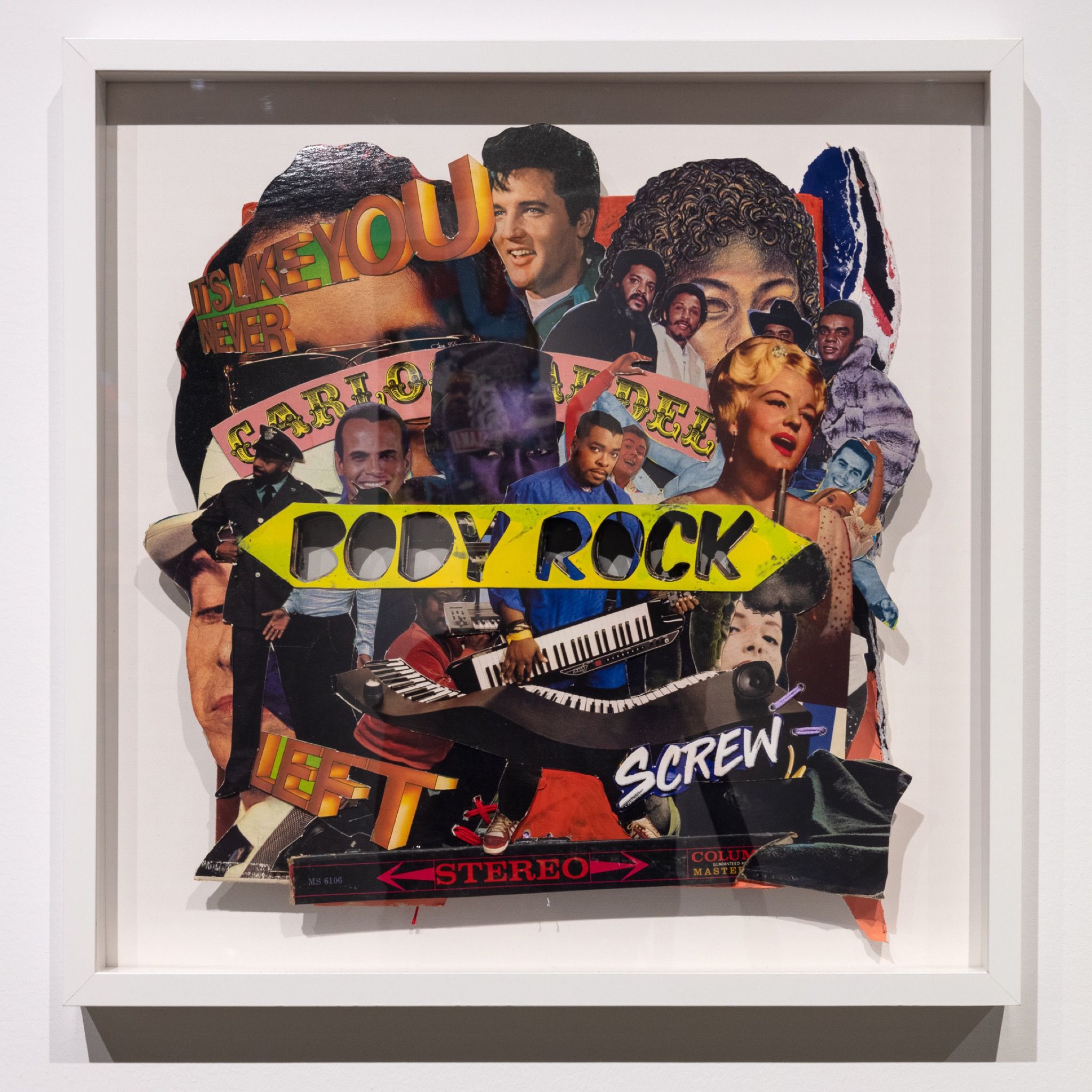

Robert Hodge: For me, it was a part of my fabric, man. This is my city. This is my neighborhood. This is the people I know. I grew up in a neighborhood with Big Moe and Chris Ward, who’s part of the Screwed Up Click. He’s one of my brothers. So the music has been part of my life forever. To me it wasn’t even a thought process. When I started making it work, I already knew DJ Screw’s practice, and knew it was similar to how I make collages. I didn’t have to sit down like, how am I going to approach this exhibition? It was just like, oh yeah, this makes sense. I just went at it very organically. It was really harder for me to explain why it was so attached to it than making the work. I would talk to people about DJ Screw in detail because I assumed they knew, and I realized how many people did not know. You do something as a part of you, and it’s really hard to communicate it because you’re just so naturally always doing it.

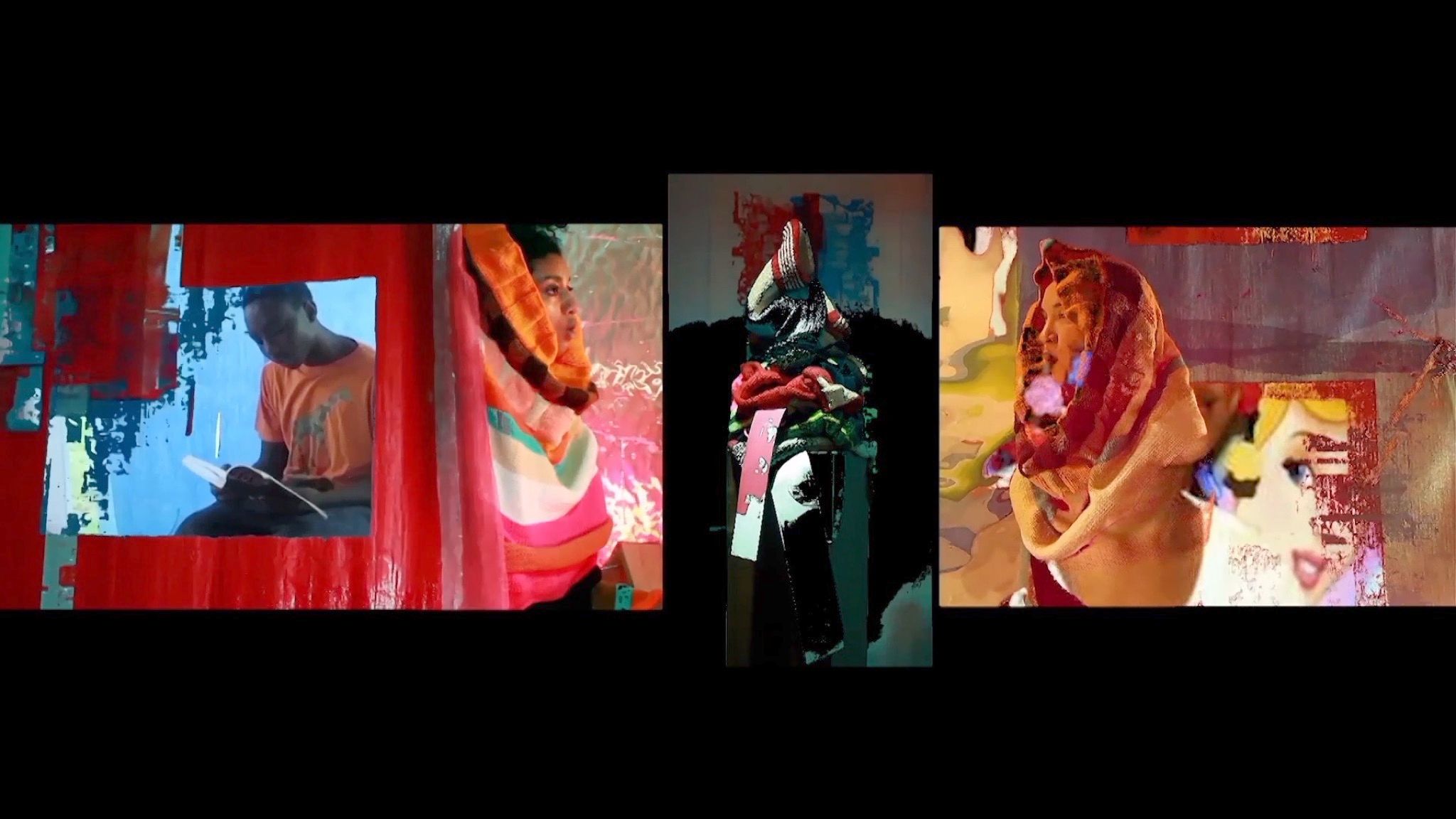

Tay Butler: I’m a migrant to the city, so I’ve only been in Houston since 2015. The culture was something I noticed. I’m outside, I’m running in the streets and cars passing me by are playing Screw. That’s not something I was used to – I was used to the Midwest, to Twista and Chicago music. But since I’ve been here, I’ve completely just submerged myself in the culture. I play so much Screw now you would think that I am from Houston. Cats from back home be asking me how have I let Houston change me so much. It’s just something that happens naturally. Like Robert, I do collage just naturally in my work and my practice, period. It was just a natural fit. I use collage as a way to confront Black history and things that have happened before, but not wanting to try to interpret or convert something into something else. I want to use the source. And that’s what I think Screw was about. Like, “hey, I’m using the source, you’re going to see directly where my influence has come from.”

“I play so much Screw now you would think that I am from Houston.”

How might this chopped and screwed practice serve as an art critical model? When you think about hip hop – hip hop is postmodern.

RH: I think some of the main things that are important about DJ Screw was the sense of community and the sense of the man really having made an authentic practice. He took something that existed and made it something that was his own, which is extremely hard to do. You’re looking at a young man that brought different people together from different neighborhoods and kind of made Houston this force, in terms of artists coming together and having a collective. You got somebody that leads the pack in the right way, who’s not concerned with fame. Screw’s not trying to put himself on. He just wants to make great art and he wants his friends to get out of the environment they’re in and be able to be successful. He allowed it to happen through being really generous with his time, his energy, and his home, letting it be open to people to come in and make music. The way he took the culture of selling tapes, it was like dope – to the extent that cops raided the house thinking they were selling drugs [in there] because it was a long line outside. Just the entrepreneurship in it was really impressive. Tay help me out, I’m trying to bring it in terms of art.

TB: I think of it like every art movement had a counter movement, right? So you have your expressionist painters who are trying to be the counter to realist painting, and then you have your abstract expressionists, then you have your pop art. I’m going out on a limb here, but Screw represents the next entry into actual American music-making after hip hop, after jazz, right? Where we’re taking something that’s never existed, we’re creating something and we’re putting it into the lexicon of music. And we made it, you know what I’m saying? We made it.

RH: You take something already existing that you know very well, you chop it up and play with it, and it becomes something new, but it’s familiar because it’s from pop culture. I mean, that’s when it becomes a collage.

TB: It also comes from improvisation, right?

RH: Absolutely, yeah. Jazz and psychedelics – people would take acid then, so then you got this thing that makes you kind of hear the music. When you drink that tea and you kind of experiment with music, I think it kind of opens the gateway to hearing that slowed up pitch and being like, “Yo, that sounds great, let me keep playing with that.”

I think that notion of it being beyond hip hop, beyond jazz, but still using those structures, is getting somewhere. When you’re hearing an Elton John song mixed up with an Ice Cube song and it’s chopped and screwed – people aren’t doing it thinking they are going to be “big artists.” They want to get stuff off their chest, to come together around that, and do it in a way that’s accessible, for hundreds of thousands of people who didn’t know you. And you can’t talk about it without talking about some of the causal things that were happening during that time, because that’s not a full story.

RH: Making something organically from the heart because you want to and you’re just having a good time – that’s where that good music comes from, man. There’s no pressure, because like I said you got a comfortable place when you come with your homeboys, and you guys are making music, you can pop in. That’s when all the magic happens, man. So I’m not surprised that’s something that is lasting as long.

“That’s when it becomes a collage: you take something already existing that you know very well, you chop it up and play with it, and it becomes something new.”

So as artists, what does it mean to you to preserve the underground culture of an underrepresented community at an institution like both of y’all have?

RH: I thought the exhibition was very important, but I was nervous as well because a lot of times people don’t get it right. The people that know Screw really well, that’ll make them very angry. And I got to give a shout out because it was a very diverse, well put-together show, and it’s kind of hard. Especially considering the space we had in the camp – it was not a room for archival stuff. They recreated the store. ESG was involved and Big Bub and all the people that really were important to Screw were involved in the show.

TB: Did you catch wind of the controversies last year at The Whitney Museum – them doing an exhibition with works they got at benefit auctions cheaper than what they were selling it for? It’s a double-edged sword, because they don’t do these shows, and then when they do do them, they usually get it wrong or it’s a total tragedy.

How can we respectfully tell the stories of those who have died young or suffered from trauma while acknowledging the disparities of our society from a place of privilege? Art is extremely expert at jumping between all the layers of class and society, so how can we use it to tell those authentic stories?

RH: The bio movies that really hit hearts tell a layered story. Ray worked for me because I got to see the whole totality of Ray Charles, the drugs, the adultery. I mean, if somebody was telling my story, I would want them to tell all this shit because that’s what humanizes you and makes it say, “This person’s not really special, it’s just: through their circumstance, they create art, even at the bottom of the bottom.” That’s the only justice you can really do to someone’s life – when you glamorize it, it makes it feel like it’s unattainable. It’s not about that. It’s about just pushing through what you’re going through and making art at the same time. Brother Chad from Black Panther died [last year], what’s so unique about him is this man was going through colon cancer treatment and making these movies, not complaining, not saying nothing. That’s what makes the story so beautiful – because it wasn’t perfect. He was in pain, still going, still making his art. And that’s all artists do, while we all going through shit. Simple as that.

TB: You know what it is hard? To know that your story is worth telling. You know what I mean? When you’re living it, you’re in it. I don’t know how we get to a place where we know that what we’re doing is going to mean a lot to different people, to a lot of people. Screw has gone on to create multiple versions of rap, from alternative to chill wave to all of these different types of genres that have a direct line from what Screw did. So how do you come out of yourself or come out of the culture to see that what you’re doing is worthy of being documented and told? Then you’ve got to have people in place in these institutions that want to tell these stories – people who have enough sense or courage or the freedom to tell the story. You have to have somebody – unlike the people at the Whitney who’re just thinking about the dollar, right? – that’s thinking about the cultural impact. They have to believe that that story is worth telling because wow, there will be people who complain and say, “Why did CAMH get that show?” Maybe [other institutions] didn’t see the value in it. Maybe they were too busy thinking about the drug culture link, right? So then respectability, politics, and all of that kind of crap comes into it. So it’s not always per se that it has to be somebody black, But it’s got to be somebody that feels that Screw is worthy of being elevated to another level.

RH: There might be an inclusion of people of color, of black people in the board rooms, on staff, as part of the administration, writing their literature. That makes it authentic too. Like the thing that the Whitney did – that happens a lot because there’s nobody in the room saying, “Hell no.” Because that perspective is not in the room. So you can’t even see the insensitivity of what you did. Nobody’s saying “That’s so disrespectful on so many levels, man.” Budget is a big thing too. You got rappers who are living, who want the history to be there, but people need to be compensated too. You got to take care of people that are living, that are part of that history, and at times people are skipped over because institutions don’t want to make those payments.

TB: You’re just giving people the roses while they’re alive to see them.

“Slowed and Throwed” is curated by Patricia Restrepo, Exhibitions Manager and Assistant Curator, Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, with guest curators Big Bubb, Owner of Screwed Up Records & Tapes, and ESG, rapper and member of the Screwed Up Click. The exhibition is also made possible through the assistance of Research Advisors Julie Grob, Coordinator for Instruction and Curator of Houston Hip Hop Research Collection at the University of Houston Libraries, and Rocky Rockett, independent hip hop educator. The artists featured are B. Anele, Rabéa Ballin, Tay Butler, Jimmy Castillo, Jamal Cyrus, Ben DeSoto, DJ Screw, Robert Hodge, Shana Hoehn, Tomashi Jackson, Ann Johnson, Devin Kenny, Liss LaFleur, El Franco Lee II, Karen Navarro, Kristin Massa, Ayanna Jolivet Mccloud, Sondra Perry, and Charisse Pearlina Weston.

Credits

- Interview: Jeffrey Martín