LACATON & VASSAL: Game Changer

Today’s architects “produce” more than they build. They teach, give talks, make books, make exhibitions, make art, and now and again, they design buildings. Academics have been moaning for a decade now about how the profession has lost its way – that without the crutch of a widely adopted “-ism,” most practices have simply gone the way of the market. The high mindedness of modernism, the idea of architect as hero worker, and the staunch (though often superficial) conviction that architecture is not merely a service industry, but a humanist, intellectual pursuit all seem quaint when faced with an actual chance to build.

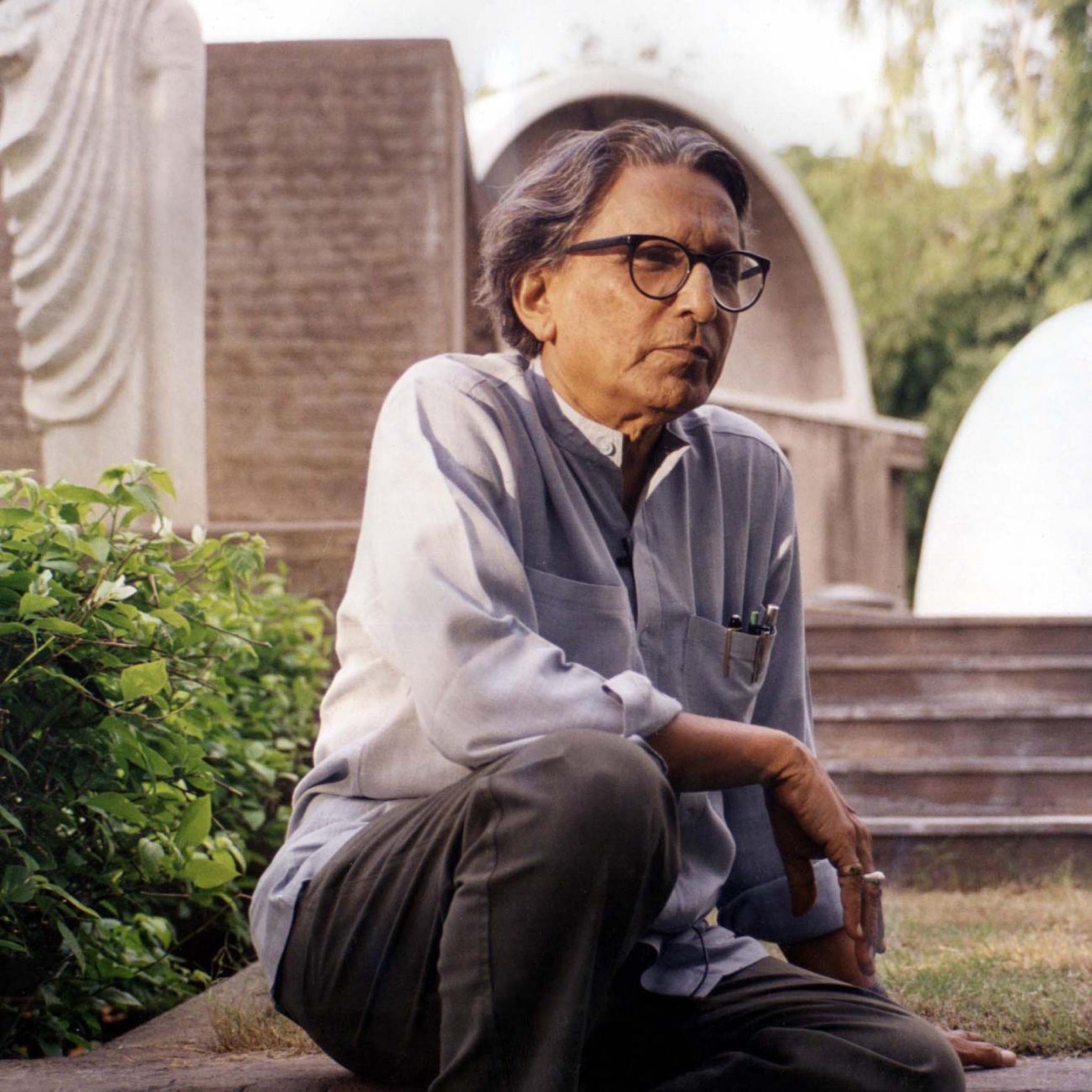

For the last 20 years, Anne LACATON (57) and Jean-Philippe VASSAL (58) have been working out of the top floor of an industrial building, set back from a busy intersection between Gare de l’Est’s tracks and the Canal Saint-Martin in Paris. The morning I was there in late spring, their office had the warm hush of a library – this despite the fact that in a few days, their major renovations for the Palais de Tokyo, would be revealed to the public. The office is large and no-fuss. Fifty people, I reckon, could work there with relative comfort, so the dozen or so architects at their computers that morning had their work generously spread about. Shelves of books, magazines, and folders filled with bits of building material line a few walls; an old Cedric Price catalog had the InterAction Center dog-eared and collaged with Post-it notes. The InterAction Center (1976, Kentish Town) was a reduced, bargain version of Price’s ambitious and visionary Fun Palace (1960-61). The InterAction Center was modest yet built; the Fun Palace was grand and enterprising, though remains imaginary.

We sat at a table close to the books. They both speak with equanimity; their cadence is unhurried, their bodies sit with distributed ease. The two met in architecture school in Bordeaux. In 1980, immediately after graduation, Jean-Philippe went to Niger to work as a town planner. Anne would visit him there, all the while admiring the efficiency of everyday solutions that she saw around her. A piece of cloth tethered to a tree provided shade. A branch, horizontally affixed, was a barrier. Lines drawn in the sand marked territory. Architecture, the practice of determining our lived environment, is about innovating the world around us; rarely does this require the invention of eccentric forms.

For most, particularly non-architects, the name Lacaton & Vassal won’t immediately conjure any mental images. Even those who have visited their buildings often wonder what it is exactly they have designed. Where, upon the exposed concrete beams and columns, the raw expansive rooms of the Palais de Tokyo (2001–11), have they inscribed themselves? (They tore down unnecessary floors and walls to open up the space, allowing it multiple usages.) Their houses in Coutras (2000), in Aquitaine, look virtually indistinguishable from commercially available polycarbonate greenhouses common in the area. In 1996, when the city of Bordeaux asked them to re design and improve the dowdy looking Place Léon Aucoc just south of the rail yards, the young architects, after some months of study and observation made a proposal. Do nothing. It’s fine. Leave it as it is.

Not long ago, when asked about the most radical position an architect could take today, urban theorist Pier Vittorio Aureli answered “do less, travel less, produce less,” and though Lacaton & Vassal would certainly welcome more projects into the office, what they do, and how efficiently they do it, has been quietly setting them apart from the glut of Viagral practices that sell high on spectacle, and low on everything else.

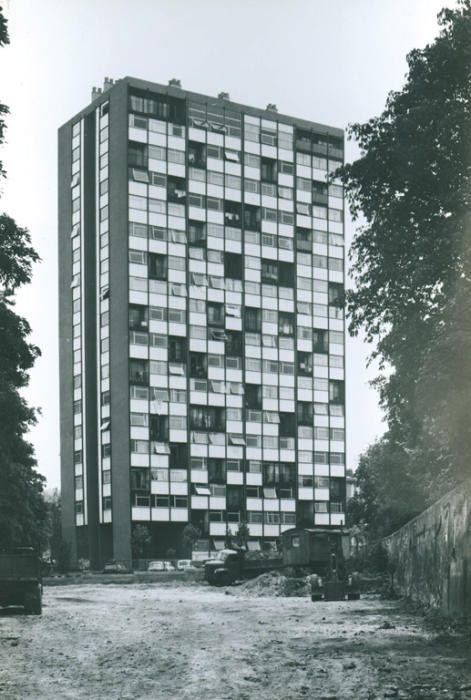

Lacaton & Vassal remind us that the architect’s work cannot be reduced to the single role of building designer. Against the trend in France to demolish outmoded post-war housing towers to make way for newer ones, Lacaton & Vassal, together with Frédéric Druot, argued for and won the chance to renew at least one such building. On the edge of the 17th arrondissement, Raymond Lopez’s 1961 16-storey stack of flats is expressionless and nondescript. The units are small, there is little communal space, and despite its height, the building’s small windows seemed to purposely deny its occupants the Paris skyline. Lacaton & Vassal’s proposal was about two-thirds the cost of razing and rebuilding, though their primary concern was not budgetary. Above all else, they aimed to optimize living conditions of the residents. As with the Palais de Tokyo, excess walls were removed to liberate useless enclosures, and a three-meter sleeve of extra space was pulled over the entire building. It took just one day to retrofit each apartment with its addition – people left in the morning for work, and returned to see their façade wall removed and replaced with floor to ceiling glass, a winter garden and balcony. No one had to move out, less money was spent than demolition, apartments were expanded, and everyone has an impediment free view of the horizon. Sunlight washed in; the breeze lingered. What Lacaton & Vassal express, if not style, is an ethic of building — an imperative for design. This is their acclaim (they’ve won virtually every prize available to architects in France), and in the world of architecture, confused and wayward as it is right now, drunk from years of oil-fueled economies and unhinged by extremist urbanism in China, Lacaton & Vassal ventilates the profession’s inflated hubris and distills its power, if not its role, to enhance our living.

Alexanderplatz in Berlin was like this 20 years ago. There is little that is architecturally scripted at Djemaa el-Fna. It changes everyday and it was exactly this kind of FREE ORGANIZATION we wanted to establish at the Palais de Tokyo.

CARSON CHAN: You just reopened the Palais de Tokyo after 10 months of renovations. Lacaton & Vassal renovated it in 2001, I read that your design then was based on the Djemaa el-Fna square in Marrakech.

JEAN-PHILIPPE VASSAL: It’s been a while since I was last there, but the version of it in my head was what guided our first renovation of the Palais de Tokyo. It’s a large open space, a public space where the activity is constantly changing and evolving. Djemaa el-Fna is empty early in the morning. A car would drive across the plaza and without any visible marks, it would inscribe boundaries that other users of the space would follow. Vendors come to sell fruit, crafts; storytellers and street performers follow. An audience gathers and cars and motorcycles change their paths as the crowd grows. We referenced this feeling of a place that is always moving, transforming, where everything is accommodated. It’s a place the people of Marrakech show up to everyday. It’s open, but not a void.

ANNE LACATON: Alexanderplatz in Berlin was like this 20 years ago. There is little that is architecturally scripted at Djemaa el-Fna. It changes everyday and it was exactly this kind of free organization we wanted to establish at the Palais de Tokyo. We wanted to bring the crossovers of program and actions that usually takes place in outdoor public spaces inside. After architecture school, around the mid-1980s I was often in Niger to visit Jean-Philippe. There weren’t so many buildings where we were, but I was amazed to see the people there do very simple things to make really effective architecture. Cloth tied together and strung up with some branches is a makeshift tent that provided shade and allowed people to work. I realized that architecture is so much more than form and aesthetics. It’s so much more intelligent than that.

I think it’s important that architects understand the life that happens without buildings. It’s the rare architect that denies their ego to say, “In fact, I will notbuild.” Unbuilt projects are common inarchitecture monographs, but I was surprised to see you included the PlaceLéon Aucoc in Bordeaux (1996) in your2010 2G monograph. It’s not an unbuiltproject. You denied the commission tobuild there. You’re proposing that architectureis as much about not buildingas it is about building.

JV: There is a general misunderstanding about what an architect does. Do they build things out of metal, steel, concrete, wood, and glass or are they building spaces, situations, and places for living? Those I would say are the architect’s real material. When we see Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House (1951), we don’t see the steel beams and floor plates. It’s a building about the relationship between climate conditions, different levels of intimacy, degrees of privacy, the condition of living in a green landscape, and so on.

AL: Architects work with movement. Architects don’t just build buildings, they build a relationship with a site. The project brief we got for the Place Léon Aucoc in Bordeaux was to make the square more beautiful. We considered this charge, went to the site, observed it carefully, and after several trips, we were totally convinced that it was already beautiful and it was not necessary to make it more beautiful. They probably hoped for us to change the streetlights, the ground cover, the benches, but we found that some very small adjustments would improve this place. In the end, we made suggestions on how to care for the trees, and added some new gravel.

That’s brilliant, but what did the client say afterwards? Architects build partly to become visible in a highly competitive economy of building. To participate in an international community of design requires architects to make certain forms, no?

JV: But I would say that the project is already known and visible. We’re talking about it right now.

Did the client go and find someone else that would carry out their wishes?

AL: At first they said, “ok, we’ll find someone else if you don’t want to do it.” our response was, “We do want to do the project, and our project is to do nothing.” After three months of discussion, they were convinced that we had done a good project. They said “okay, you’re right.”

Does the world need architects?

AL: The world needs architects because they have knowledge that others don’t. Everyone knows how to cook food, but we have people for whom it’s their work and they make it better. For many, even if they want a simple spatial solution, they won’t know where to begin. In fact, doing simple things is often the most difficult.

A plaza or public space that has been heavily published recently is J. Mayer H.’s Metropol Parasol (2011) in Seville. The project with the large mushroom cloud made of wood. There was a lot of building that happened there, it took a long time, and it was very expensive, and now there it is. Many have argued that the structure’s iconic stature has allowed it to participate quite quickly in civic life. For example, it was the site of protests last year in Seville. The building gave the protests another form of visibility.

JV: Don’t you think it is possible to create meaningful events in Seville without this building?

Of course.

AL: Expensive architecture is needed by a very small circle of people: other architects, politicians, and an elite group of decision makers. Is it needed for the general population? Is it needed for all inhabitants?

JV: It’s not obligatory to make buildings to change the city. We could very well make events. We ask ourselves if it’s possible to make interesting architecture, even extraordinary architecture, without monumentality.

Architectural icons are museums and opera houses, but what if the city’s icons were some truly interesting living conditions or new types of housing? That would be very CONTEMPORARY.

When do you think this shift started? With the worldwide attention given to Frank Gehry’s Bilbao Guggenheim (1997), a lot of people are still waiting for the next Bilbao effect, this monumentality effect.

AL: Who says that? Who asks for that?

A lot of cities, in China.

AL: Well, we should think more deeply about where and what the city’s icons should be. More often than not, architectural icons are museums and opera houses, but what if the city’s icons were some truly interesting living conditions or new types of housing? That would be very contemporary. That would be very interesting for the future. It’s very disturbing to see that in many countries there is so much money to build museums, to build these very big buildings, and so little to build housing. In France it’s the same. If you are making a museum, the budget is pretty free. If you are working on housing, you must work with great effort to make marvelous things with very small budgets. Our definition of the architectural icon needs to change, to be updated.

Your unbuilt design for the Architecture Foundation (2004) features a seated statue of a 32-meter tall woman. She occupies about a third of the space. On the second floor, visitors are confronted with her giant breasts. I would say that this is pretty iconic in a spectacular kind of way!

JV: Yes, but I would say that this project was still very much derived from the context. The site was a 300 square meter triangular plot of land not far from the Tate Modern.

The idea of building there seemed so out of context that you responded similarly with something out of context.

JV: The client asked for an icon, so we simply put an icon inside the building. on each level you can even touch her. The exterior was very simple, not unlike our other buildings.

The clients specifically asked for an architectural icon?

AL: Yeah, an icon of 21st century architecture. For us, the iconic is never the building, but what it is inside. Usually, like in the Palais de Tokyo, we see the most spectacular part of the building as the action and program that takes place inside. We were playing with the idea of what it means to put an icon inside so we chose to put a giant statue of Adriana Karembeu there. She’s a top model, she worked for some human rights organizations, and she’s married to a famous football player. As an image, as a symbol, she’s an icon.

Iconic architect gets attention. Iconic forms get attention. It’s pretty incredible that you guys haven’t been pressured into the cult of form making.

AL: It’s hard sometimes. People, clients, react to ideas in function of the forms they see. We’re totally convinced that through the process of thinking, of looking at given conditions, at how people behave, live, work, we can produce a project that actually works. The aesthetics of our projects are a result of what we believe to be the right decision during the design process. To be guided by how the building should function, rather than questions of materials or aesthetics, will result in good architecture. If the first question you ask as architects is how something looks, then the building will serve in function of its looks.

How much would you say you’ve been shaped by your upbringing, by growing up in the 60s and 70s in France, and for Jean-Philippe in newly independent Morocco, and having this discussion of social housing being such a prominent one at the time?

JV: That’s possibly part of it. Growing up in Casablanca, living in Niamey in Niger, has shown me that very simple architectural gestures could have very strong effects on the way we live. We’re very interested in the urban experiments from the 1970s from groups like Archigram or Alison and Peter Smithson. We were interested in seeing how these ideas can find a place today. Architecture projects could turn into urban projects. Our architecture school in Nantes (2009) was an attempt to move in this direction. Perhaps an iconic project we really like is SANAA’s Rolex Learning Center (2010) at the École Polytechnique Fédérale in Lausanne. It’s a striking object – with its curved, ramping surfaces – but it’s an object that operates fantastically in that it has made the whole campus react. It’s a small object on a big campus that has become the center of activity.

AL: Kazuyo Sejima found exactly what the campus was missing, and she provided it. To answer your question about how much my background has influenced the work we do, I would say that the quality of social housing, and the creativity and ideas surrounding it that existed in the past, has put in stark contrast the truly bad housing that exists today. Responding to this very current condition is an architectural responsibility. How do we make things better?

With the Tour Bois-le-Prêtre (2011) project, you gave each apartment of housing block on the edge of Paris a sizable extension within a day. So, a tenant would go out to work in the morning and arrive in the evening to see their apartments bigger and with new floor to ceiling windows. You did this while assuring the tenants that they would half their energy bill and the housing commission that your extension would be cheaper than to demolish the building as originally planned. This was done by adding a grid of winter gardens to two of the building’s façades, which, as far as Iknow, has never been done before. Howdid this come about?

AL: Well, as you mentioned, the city of Paris wanted to demolish these housing blocks from the late-1950s. Together with another colleague, Frédéric Druot, we wanted to find out what the alternatives to demolition are, and we found that to rehabilitate a building, to transform it anew, was far cheaper. The façades were not insulated, there was asbestos, the ground floor entrance hall was underused, and the elevators were dangerous places to be in. There were many problems for the Tour Bois-le- Prêtre. Of course, it would have been easy to spend the entire budget on a new façade and superficially improve the building, but we wanted the available funds to be used to improve the inhabitants’ lives. We started by analyzing what was missing with the living units. For one, the building’s windows were tiny, so even the units on the upper levels of the building had no real view of Paris. We took off the outer walls, added a winter garden, and in doing so allowed light to flood into the enlarged living spaces. Improving the quality of movement was a big concern for us.

You’ve mentioned the Smithsons and other modern architects, they too imagined better living conditions for people. But one can say that in retrospect, whenever architects imagined people living a certain way, the results were never really comparable to the desired effect. Despite well meaning green space, wider stairwells and large windows, housing often become sites of social problems. Have you guys prevented yourselves from repeating the mistakes of other architectural good intentions?

AL: We don’t have a negative eye about what was made in the 60s and 70s. The modern movement’s progressive narrative was not a bad one, right? What can we say against architects wanting to improve people’s lives? Perhaps modernism’s big mistake was to assume that there could be one solution for all situations. Instead of seeing past projects as failures, we see them as a good starting point for change, as potential sites of improvement. We chose not to see buildings as bad and needing to be replaced. We take them as opportunities to take what is interesting, what is good, and to take steps to transform them into something even better.

Did the tenants have a choice of whether or not to accept your improvements?

JV: When the city wanted to demolish the building, they didn’t ask the inhabitants first. We gathered everyone for meetings and voted on most decisions as a community. More than 95 percent of the tenants wanted the project. We took a lot of time to explain the project clearly and carefully.

Living in a different way is always a learning situation, right? When you took Michael Kimmelman from The New York Times to see it, he reported that some residents used their extra space for storing garbage.

AL: Sure, but we’ve also seen that with the new living conditions, people have started to self-regulate their public space as a community. When people see that a family is putting their garbage out, they will approach them and say “okay, what are you doing? Please, take care of your space.” People that have never spoken with one another are now doing so.

LUXURY isn’t related to money, but it’s the condition of achieving above and beyond what was imagined to be possible.

It’s great to be reminded that it is architecture as a social system, and not architecture as a question of form, making changes in the way people live. You can create a community by providing simple balconies. What is so powerful with this project is that it addresses the city as a constant site of improvement, rather than a graveyard of failed attempts. A city is a thing that can rehabilitate, be continually improved and calibrated into something that works.

JV: We tend not to see a city for what it is, but what it could be.

AL: Our job is to evaluate the potentials that the client doesn’t see immediately.

JV: If you look at the suburbs as they are, politicians say we should demolish them. If you look at how they could be, it’s totally different.

La Tour Bois-le-Prêtre has seemingly won every available prize in France, it’s being published internationally, and you’re both traveling around to speak about it at schools and conferences. You’ve made a housing tower from the late 50s become a desirable thing. I’m wondering how the residents of the building will be affected by all this attention? Is it possible that the people you were hoping to improve the lives of will soon be pushed out by young professionals? Have you kick-started gentrification? As it is, the city is contributing less and less to subsidized housing, and relying on higher taxes on housing companies and revenue from tenants.

AL: We’ve safeguarded against gentrification by keeping the residents within the building’s transformation process. Eighty percent of the families that were there before the project are still there and I think they intend to stay. They now live in some of the most beautiful apartments in the city. If by gentrification we mean the improvement of the residents’ lives, then I would hope to see more similarly approached transformation projects around.

JV: Gentrification is not a problem if it is gentrified everywhere – at which point, the term will stop making sense.

Then it’ll just be called improvements.

JV: It’s crazy to see how bad the quality of living is in Paris today. Forget the homelessness, even the bourgeois are living in horrible conditions. Poor plumbing, insulation.

AL: Parisians pay a lot and get very little.

JV: Most architects in France don’t think about how living can be improved. If more architects and urbanists thought this way, I’m sure in 50 years we would have great places to live in.

Over the years, I would say your methods have definitely taken hold with other architects and students. Getting to this point today, where you have so much critical attention, must have been a long journey, particularly because your work is not about being flashy.

JV: It’s been a long journey, but we don’t see obstacles as blockages to our work. Take the house we made at Cap Ferret (1998) for example. About 15 years ago we were asked to make a house on a heavily wooded site on the cape. Normally, the trees would be cut and the sand dunes flattened – they are seen as obstacles to building. The crazy beautiful site itself was exciting for us. We kept all the trees, there so that they intersected with the house. As with La Tour Bois-le-Prêtre, there are so many ways to play with what exists already.

AL: It’s about preserving what is high quality about each situation. With Bois-le-Prêtre, you can say that we found the building and the people inside of high quality, as something to preserve.

Appreciating the beauty of found situations is both poetic and sustainable, but as architects, do you guys ever dream of doing something completely out of your own desire, where nothing would be a compromise?

AL: Dreams for me have to do with ambition, good sense, optimism. I dream about keeping the sites and situations that I see and being able to improve on them.

JV: This is really a dream situation because increasingly, architecture briefs are being written and restricted by planners and politicians. They give out square plots of land and ask for an icon on it. There is little freedom in this system, so preserving optimism and freedom would be a dreamy, luxurious situation already.

I really like the definition of luxury you came up with in your conversations with Patrice Goulet. You said that luxury isn’t related to money, but it’s the condition of achieving above and beyond what was imaged to be possible.

JV: Definitely. The architecture school in Nantes wanted us to design for about 10,000 square meters. We gave them a building that is about three times bigger. Large parts of the school are completely open to the public, so in the end you can see that not only did they get an architecture school, they got an open system, a space of social mixing and potential dynamics that contextualizes the school in the center of Nantes.

So you’ve just completed the second renovation of the Palais de Tokyo. If the 2002 renovations were based on Djemaa el-Fna square, what is the model for this time?

JV: This time, we based it on Cedric Price’s Fun Palace. The open system planning of the building now extends to many levels. The first phase was only on one level. There’s vertical and horizontal movement of activities and multiple, simultaneous programs are accommodated.

AL: We tried to open every last square meter of the building. There’s very little that is closed to the public, to allow the public to explore the entire space. We’re hoping that people will be surprised by what they discover of a place they think they know.

Many people think that saving money, finding low cost solutions, and using common materials is the basis of your practice, but you’ve explained that the projects are not driven by these ideas, but by your definition of luxury, of exceeding what is expected to be possible. The effect of your collected works has produced an ethic of working, an ethic of how architects should behave, and an ethic of how to understand society. So, if you were offered, say, 100 million Euros to build an opera house in China, would you do it?

AL:Why would the Chinese want us to make an opera house?

It’s a hypothetical question. So, would you do it?

JV: Of course we would do it! But we’d do it our own way.

Text CARSON CHAN, Photography FRÉDÉRIC DRUOT and PHILIPPE RUAULT