MICHAEL SCHMIDT: THE GRAY ISLAND

HOLIDAY AGAINST THE WALL

The first time I met Michael Schmidt was by the gate of his garden in Schnackenburg, a town by the Elbe river between Brandenburg and Niedersachsen, where he and his wife Karin had bought a small house in the 1970s. Behind the house was a dyke, then the river, then the GDR’s watchtowers. It sounds completely wacky at first that the pair would drive two hours to escape the walled city of West Berlin just to settle down right back at the border. But it made sense for Michael, who got bored without resistance and tension. Besides, the wide river and sky turned this particular place into one of the more relaxed border regions.

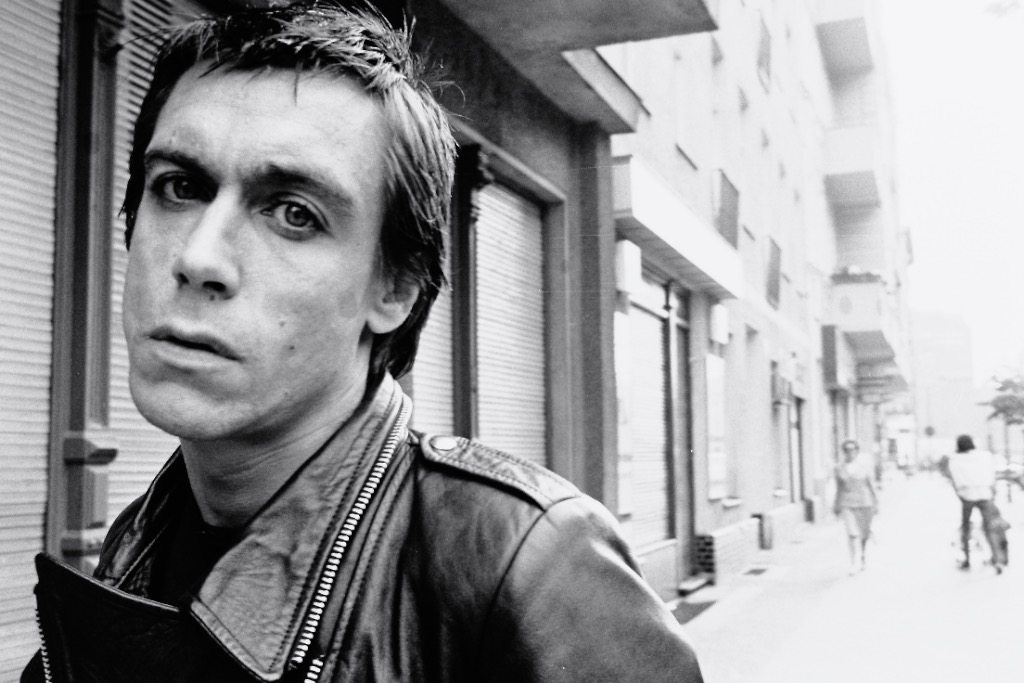

A typical German scene: house, garden, dog, Volkswagen sedan. It was shortly before the opening of Michael’s first retrospective at Munich’s Haus der Kunst. I had seen his intimidatingly sober photographs at the Berlin Biennale in 2006 and knew that he was approaching a late discovery. Strange, when you keep in mind that two of his series had already been shown at the MoMA in 1988 and 1994. I mean, Michael was 65 then, and it was obvious what he had achieved through his art. It had crashed the whole idea of insight and oversight against a firewall, pulled down the blinds to the window of the world, and created spatial situations between bodies and books or exhibitions that forced the viewer into confrontation. “A good image must carry a shock within itself,” he told me that day. In America, people knew how to appreciate this contribution to photography, although perhaps partially for the wrong reasons, in that they found an exotic representation of “The German” in his gray photographs.

Michael, one head shorter than most people, with a tougher handshake than most people, greeted me warmly with a complicit smile. He enjoyed talking and answering my questions for two hours. He explained his search for open forms with the examples of Cézanne and Picasso. He contrasted Balzac and Zola’s nineteenth-century Realism with Thomas Mann’s gestures of superiority: “I am suspicious of people who have the truth. The truth is a knockout argument.”

Was he a romantic? “If that means that I stand by my emotions and formulate them, yes. The way the word exists in usage, of course, sucks. You have to define romance differently. To defend one’s own feelings, one must formulate them in a much harsher way than back in the nineteenth century.”

Afterward, Karin invited me to stay for lunch. It was clear that it was a test, too. Michael was watching me, the young author, very closely that morning and finally decided to find me okay. I went out there a few more times after this. Michael always wanted to know exactly how work was going, how life was going, how my love life was going. It was impossible to hide anything from him. The man was ready to give his all as long as you made yourself available. Looking back, I can imagine participants of his photography courses in the 70s shaking as they presented him their new works for discussion.

Astonishingly, one thing we never talked about was Michael’s work as a teacher. I knew he followed some younger colleagues with curiosity, gave them tips, and sometimes bought their works. I knew that he was one of Andreas Gursky’s first teachers and that he had sent him to the Düsseldorf Academy to study with Bernd and Hilla Becher. But it was only after Michael’s death that I understood how big his contribution for the establishment of a new German auteur photography really was.

DARK, DARK GRAY ON DARK GRAY

Since the 1990s, Düsseldorf has been regarded as the center of German photography. Gray silos and furnaces by Bernd and Hilla Becher. Plain alleys by Thomas Struth. Magnificently lit theaters and libraries by Candida Höfer. Andreas Gursky’s manipulative, swarming photographs. All thoroughly composed, the world is discreetly brought to the lens object by object, preferably larger than life for a marveling gaze. It screams: “Photography!”

But 30 years ago, what came to mind first when thinking of German photography was Berlin photography. Lewis Baltz, Stephen Shore, Larry Fink, and many other pioneering American photographers traveled to Kreuzberg to exhibit their work at the Werkstatt für Photographie [“Photography Workshop”] and discuss it with amateurs and professionals alike. Robert Adams and William Eggleston showed their first solo exhibitions in Germany there, right by Checkpoint Charlie, and frequently traveled on to Graz’s Steirischer Herbst with the Berliners.

In 1984, Lewis Baltz and John Gossage curated “Photography from Berlin,” an exhibition at New York’s Castelli Graphics that went on to travel to Washington and Los Angeles. The Washington Times wrote: “West Berlin’s recent artistic boom can only be explained in relation to the intense claustrophobia experienced by the people living in this city. Just like patients on a heart-lung machine, their radius of movement is limited and relies on an environment that is kept alive artificially. It is therefore no surprise that the best of West Berlin’s art contains the feverish, hallucinatory vehemence of a gravely ill person.”

It was an exemplary story of artistic self-empowerment: out of nothing, a photography scene had developed in just a few years. And this was decidedly Michael’s work. It was in 1965 that Michael – who grew up in East and West Berlin, and whose brother spent nine years in Bautzen’s infamous Stasi prison – quit his job as a police officer and bought a camera. At the time, none of the universities offered photography classes. He took one of his first images at an elementary school: a girl, laying on a table, photographed from below, her eyes hidden behind thick glasses, her nose bleeding. It has the punch of his later work, which lies in its soberness. Images without embellishment, stylization – dark, dark gray on dark gray – and most importantly: without stupid sentimentality.

Back then, there was a club for amateur photography, but their understanding of art was different. “When they photographed rain, it looked like glass pearls,” Michael explained once, “When I photographed the rain, it looked like rain.”

WHAT DOES THIS PICTURE HAVE TO DO WITH YOU?

Michael was a restless doer and understood how to enthuse people. In 1969, he already taught photography courses at Kreuzberg’s Volkshochschule. He organized exhibitions for his students at Kreuzberg’s town hall. He got his borough’s mayor to finance his first book, Berlin-Kreuzberg, in 1973. In 1975, he organized his first gallery exhibition at Rudolf Springer by looking up his number in the phone book. “These are all boring,” Springer said when Michael came by to present his works the next day, “but they have method, so let’s exhibit them.” By 1976, he had convinced the Volkshochschule to finance his Werkstatt für Photographie, a self-organized institution in the spirit of 1968 that catered to professionals and amateurs alike with no conditions for admission. In four to five years of “intensive work,” the course catalogue promised to provide “the wealth of experience of a trained professional photographer.”

There is no English equivalent of the German Volkshochschule. The closest translation would be “Community Education Center.” From pottery workshops to language courses, they serve the social democratic ideal of national education. Volkshochschulen are probably the least cool places one can imagine. Besides a flash and a natural light studio, and a black-and-white and color darkroom, the Werkstatt für Photographie consisted of two rooms that hosted exhibitions as well as classes, one of them a walk-through room. Photographs from the time show the prosaic hanging of the images in a passepartout manner with cheap frames, hung from a bar with wires. An office palm tree stands in the background.

The way Michael described the intention of the Workshop, technology and medium were not the main focus: “We try to help the students recognize or find their personality,” he wrote, “The person’s personality is the essence for us. Only through that recognition can photography be created, and never the other way around. Many photographers go about it the wrong way and make the medium the highest priority in their lives. They let a thing rule them, instead of understanding it. But one can only reach understanding by learning to recognize oneself. This is why self-knowledge is the main focus of our work, without it drifting off into group therapeutic ‘psychologizing.’”

“The man with the camera is here for all friends of photography,” an article in the Tagesspiegel said, advertising the Workshop’s opening. In it, Michael gave tips such as: “Get close to the object,” or, “Get on your knees in front of children. One should always show them at eye level.” 217 students were enrolled in September. 304 applicants were put on the waitlist. Some courses were led by Michael’s former students Ulrich Görlich and Wilmar Koenig, who later both took over administration, although there was never a singular boss. By the time of the Workshop’s closing in 1986 – ten years after its opening – they had offered more than 200 courses to over 2,500 students. The question was always: “What does this picture have to do with you?”

AUTHENTICITY OUTWEIGHS FORM

In the 1979 March issue of Camera, the magazine’s publisher Allan Porter introduced Michael Schmidt and his peers. Ulrich Görlich’s unspectacular forest photos and grotesque self-portraits, in which he pulled his lip or nipples. Wilmar Koenig’s ruthless close-ups of unforgiving Berliners. And explorations of West Berlin by Michael, who increasingly entwined the social criticism of documentary photography with his own subjective, fragmented view. “They prefer acting over dreaming,” Porter wrote, “They are hard workers who understand and attempt to capture their Berlin in all its depth. Personal commitment matters more to them than commercial intentions. They refrain from extravagance, instead looking for honesty through which authenticity outweighs form.”

As is typical for Berlin, the scene was not focused on itself exclusively, but rather in constant exchange with Hannover – where Heinrich Riebesehl founded the photography gallery Spektrum in 1971 – and Essen – where professor Otto Steinert passed on his journalistic approach to a new generation of photographers at the Folkwangschule für Gestaltung. Berlin’s scene included Stern photographers, too, who presented their first exhibitions at the Workshop in Kreuzberg. After Steinert’s death in 1978, the Berliners regularly traveled to Essen for workshops. Michael taught at the Folkwangschule for years – the only thing he lacked for a professorship was his missing university degree.

Mostly though, connections were established with the US, through which the exhibition “New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape” was brought to Berlin in 1978. Three years earlier in Rochester, New York, it had popularized a whole new style. And then, one after another, its protagonists arrived. Lewis Baltz. Robert Adams. William Eggleston. Larry Clark came as early as 1981. And many of them held workshops in Kreuzberg. In 1985, even Robert Frank came, whose 1958 series “The Americans” had freed auteur photography from its journalistic mandate. American contacts were developed by Wilmar Koenig, whose English was best, earning him the nickname “American ambassador.” Koenig later went on to run the Workshop and, thanks to his striking face and horn-rimmed glasses, was a popular subject of his colleagues. Now, he tells me, he dreams of reviving the Workshop in his house in Brandenburg.

They “wanted to learn from the Americans,” Michael once told John Gos- sage, whose series “Stadt des Schwarz” [“City of Black”] closely resembled Michael Schmidt’s epochal “Waffenruhe” [“Truce”] from 1987. “The USA seemed to produce the most interesting work at the time,” Gossage explained later, and the Kreuzbergers “wanted to know how it was done. What may have been true at the time has been turned 180 degrees by today.”

THE BELLIGERENT DOG

This past winter, three exhibitions in Berlin, Essen, and Hannover brought the Werkstatt für Photographie back into the discourse, accompanied by a heavy book closing this gap of photographic history. For example, there were Uschi Blume’s photos taken at a Steglitz punk club. Thomas Leuner’s participatory observations from a Kreuzberg nudist commune. Andreas Horlitz’s strong 1981 series “Essen, Frühling” [“Essen, Spring”], which combined nighttime shots of the city with television images. There was an installation by Volker Heinze that saw him pinning differently-sized snapshots across a wall: a close-up of a bottle opener on the table, a TV antenna over the Adriatic Sea, Wilmar Koenig at the bar. You have to imagine this was pretty much exactly like a wall by Wolfgang Tillmans, except in 1986 and in Essen. Tillmans told me, however, that he had never seen it. When Düsseldorf established itself as a synonym for German photography in the 90s, it was partially by coincidence and partially through successful networking in a region whose inhabitants were much more affluent and arty than Berlin’s. But maybe this also happened because Michael was such a belligerent dog who would not compromise just to get himself and his peers into something. “I need to chafe at things,” he said, explaining his laissez- faire attitude towards personal sensibilities. Some wounds are palpable still today. Michael’s affection was always strict. But for those he respected, he was a generous, curious, and helpful friend.

Düsseldorf’s path was cleared in part by the closing of the Workshop in 1986. Its last exhibition, “DDRFOTO,” introduced the most interesting photographers from across the border. The senate provided financial aid and a contact to the GDR’s National Art Trade for this. Under the pretense of it being a commercial exhibition, Wilmar Koenig and Gosbert Adler were issued work visas that allowed them to travel freely in the GDR if accompanied by an Art Trade employee. In the end, the government prevented the export of works by Gundula Schulze Eldowy, Arno Fischer, and Thomas Florschuetz. After a few months wait, they simply tore up an existing catalogue and pinned its reproductions to the wall. Kreuzberg’s Volkshochschule now had a new director who was intent on slashing the budget. The members of the Workshop preferred to shut the whole project down themselves instead.

THE LAST INVESTMENT

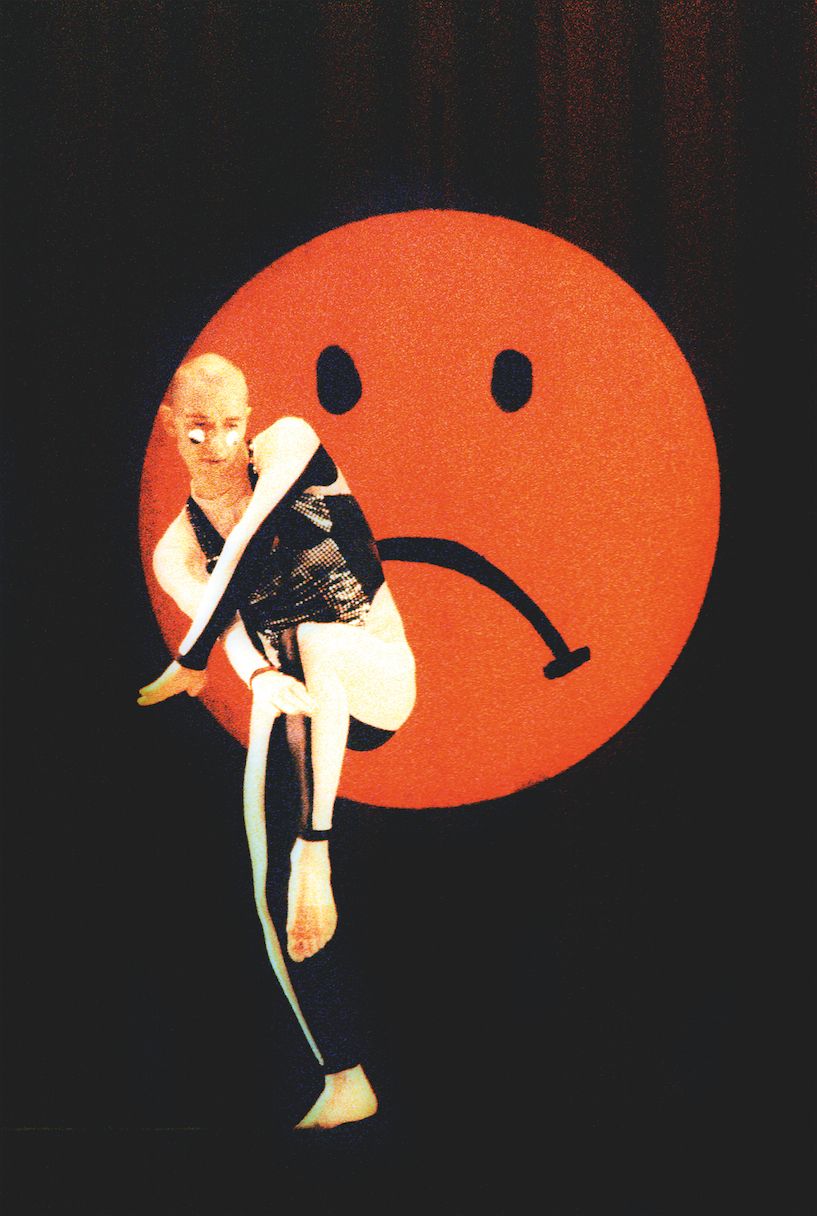

In the end, out of all the Kreuzberg and Essen photographers, only Michael achieved fame. And even he only did so toward the end of his life. In 1988, the MoMA dedicated a solo exhibition to his iconic series “Waffenruhe.” In 1994, they showed Michael’s masterpiece “Ein-Heit” [“Uni-ty”], which questioned the illustrative character of photography by photographing archive material, reproductions, and completely insignificant themes like curtains, all heightened by his technique of cutting, repetition, and mirroring.

But as a devoted reader of this magazine, you might be reminded of Michael Schmidt, too, because of how his art inspired the thought and form of 032c, and whose photographs of 70s and 80s West Berlin graced its fourth issue 15 years ago. Details, concealments, blocked views. Images with no claim to completion or universality. Images that do not simply show something, but throw viewers back into the space between the image and themselves.

Schmidt’s first big solo exhibition in Germany, curated by former Werkstatt student turned renowned photo curator Thomas Weski, took place at Berlin’s Haus der Kunst in 2010, where he hung the series “Ein-Heit” on each one of the big hall’s four walls – boom boom boom boom – all at the same level. Before that, the 2006 Berlin Biennale had brought him back into the international discourse. Its co-curator Massimiliano Gioni also showed Michael’s series “Leb- ensmittel” [“Groceries”] at the 2013 Venice Biennale. By visiting cattle ranches, vegetable fields, and shrimp peeling operations all across Europe, Michael had returned to his roots of documentary photography and the “New Topographics.” For the first time, he let some color bleed into the gray he had become famous for. In 2014, “Lebensmittel” was awarded one of photography’s most prestigious prizes, the Prix Pictet. Unfortunately, he never found out. He died two days later.

Even from his hospital bed, Michael spent time working on two books with his assistant Laura Bielau. He merrily dictated to us which wines were worth investing in at the moment. We should have drunk those together. But, well, life can be a bitch. Rest in peace, Michael.