Anti-Ballet & Post Punk: MICHAEL CLARK Reflects on 30 Years of Choreography

|JAN KEDVES

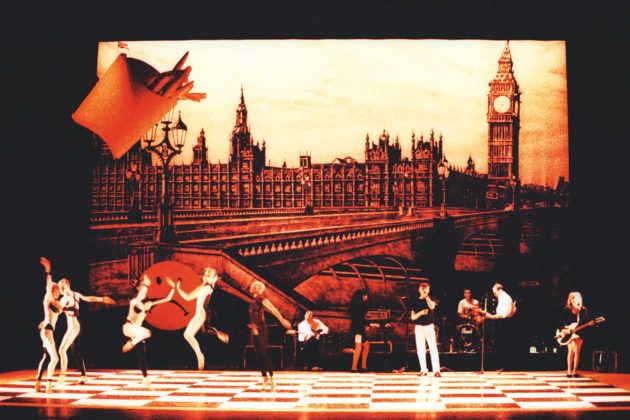

Once the enfant terrible of contemporary dance, choreographer MICHAEL CLARK is now celebrated for his untiring quest to break free from the restrictions of traditional ballet. Over the last three decades, he has collaborated with bands such as The Fall and artists such as Charles Atlas, and has become a pop icon in his own right. He has even won the approval of the Queen Elizabeth II, who will award Clark with a CBE this year.

Clark speaks with JAN KEDVES about punk, working with MERCE CUNNINGHAM, and feelings about his recent commendation.

Congratulations, Michael Clark, you’ll be awarded with a CBE – “Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire.”

Yeah, I got this letter in the post one Saturday, but I still don’t believe it really. I think they must have gotten the wrong person.

Certainly not. Your second name is Duncan, isn’t it? They have your full name in this year’s list of nominees: “Michael Duncan Clark. For services to dance.”

Yeah, it’s interesting they put the “Duncan” in. It’s my mother’s maiden name. In the letter they asked me, “Would I accept the CBE, if I got given it?” I found that quite funny. I guess they want to make sure that you don’t embarrass them at the ceremony, standing in front of the Queen at Windsor Castle, saying, “No, I don’t want it.”

Will you accept the honor.

That’s a big question! I’m Scottish and I was a supporter of the Scottish Nationalist Party in my youth. I used to wear the SNP badge, which was quite an extreme statement at the time – a bit like wearing a Swastika. People would hate you for it! I didn’t want to have a Queen. Now, I must admit I feel a little honored. I mean, I’d rather be a Knight than a Commander, and I’m told accepting the honor will probably have some uses. Charles Atlas, my good friend and collaborator, said, “It will be useful next time you get arrested.”

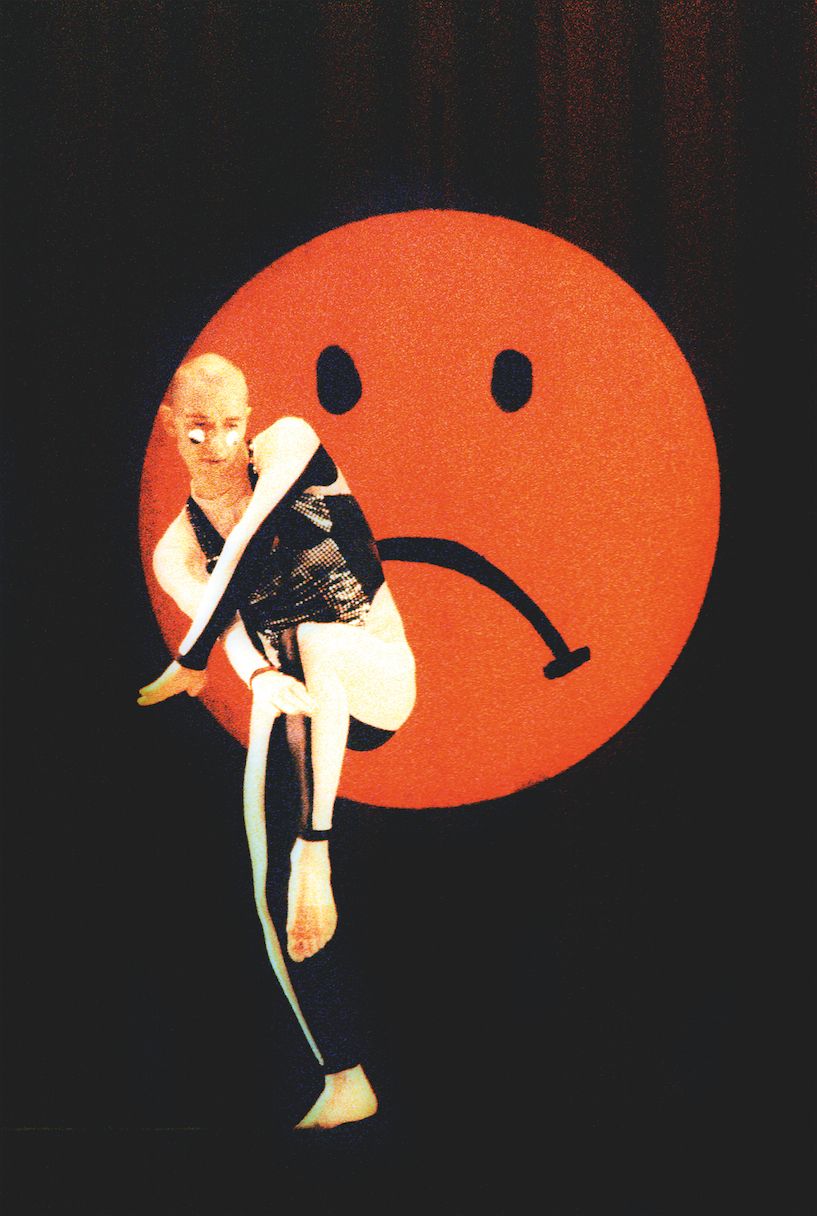

Speaking of your “services to dance,” they began in the early 1980s when you started to approach classical ballet with a strong punk sensibility. Would it be wrong to sum it up like this?

Well, looking back at it now, I have to say that a lot of it was quite superficial. It was easy provocation with costumes or props – like the middle finger, or costumes with bare asses, or dildos on stage. It was often about extraneous things, not necessarily about the dance. But back then these gestures were important, because ballet is so rigid. There are so many things forbidden in ballet – things that I embrace, like flexed feet for example. They are considered to be “anti-ballet.”

In the 1970s – when you were a prodigy at the Royal Ballet School in London – a traditional career path seemed predestined for you. But you turned down an offer to join the Royal Ballet and, in 1984, you started your own company.

Yeah, because I wanted to do different things with ballet – like, for example, work with un-trained dancers. Some of that came from Postmodern Dance, from the Judson Dance Theater in New York. Yvonne Rainer started having non-dancers in her work in the 60s, and that’s always interested me.

One of the non-professional dancers you then worked with was your mother Bessie, who is a nurse by training. In 1992, she appeared topless in your piece Mmm….

She played a sage in the piece, so I guess it made sense that she had no top on. But I never really thought about it that profoundly. I still remember what happened to my nephew back in Aberdeen. At school he was taunted by a fellow student who had heard about the piece and asked him, “Is it true your grannie’s a stripper and your uncle’s a poof?” Poor boy!

Your current piece animal / vegetable / mineral seems to almost have autobiographical traits in the sense that it appears to reflect your own experience as a young person studying ballet. It opens with a dancer doing warm-ups at an imaginary ballet barre while music from the post-punk band Scritti Politti plays. One is tempted to imagine the young Michael Clark 35 years ago at the Royal Ballet School who probably thought, “When can I dance to more exciting music than this boring classical stuff?”

It’s absolutely true. I’ve always had a very strong relationship to music, to punk and pop – David Bowie, Iggy Pop, Sex Pistols, especially The Fall. The Fall’s song “New Puritan”was kind of a clarion call to me, not just because its rhythm is so ramshackle. When you listen to it, you wonder, “How the fuck do the musicians stay together?” Apart from that, the song encouraged me to say, “Wow, I’ll do it just like Mark E. Smith!” You know, “New Puritan” was against the idea of a big company, and I didn’t want to be employed by anyone. I didn’t want to sign a contract. I wanted to make my own work. I wanted independence, my own company. Mark E. Smith was definitely an example for that.

In “New Puritan there was this one very memorable, almost prophetic line.

“The conventional is now experimental / The experimental is now conventional” – I love that line and I get goosebumps just thinking about it. It’s genius! Sometimes I think the whole world has turned into a Fall song, which is really sad. Today the world is really run by big companies, politicians have no meaning anymore. And it’s bizarre what’s considered culturally valuable. Now, value is all about money, not about the real sense of value. There’s been a total reversal.

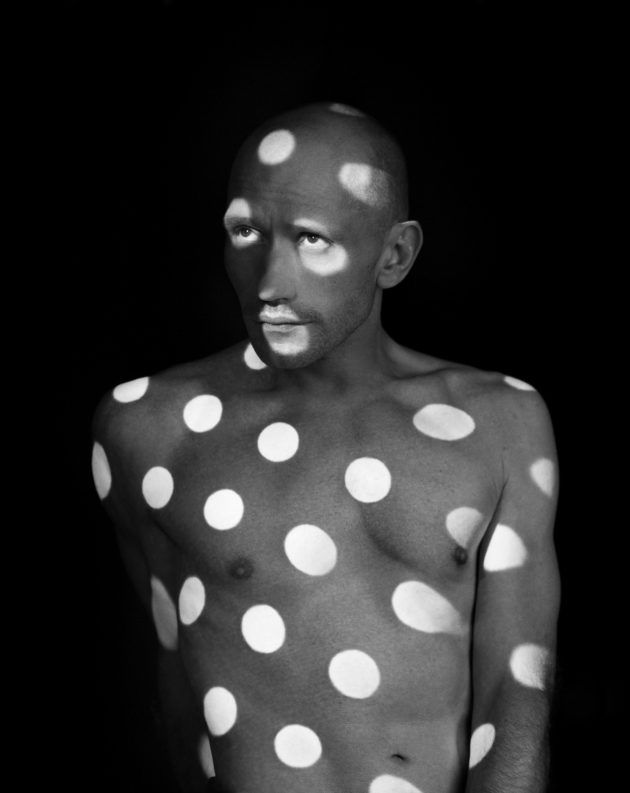

It’s also true in the world of dance, where what was once considered shocking and provocative is now bon ton. In 1989, when you performed all but naked at the D’Offay gallery in London, there was still a real outcry.

Yes, and people had to pay 50 pounds each to see that, which was kind of a statement in itself. I was making people pay a lot of money, because it was set in a different context. I wanted to see what I could get away with, really. And concerning being naked on stage, you know, there’s that saying, “Dance is a vertical expression of a horizontal desire.” I remember somebody from the Hebbel Theater in Berlin – it might have been its former artistic director Nele Hertling, but I’m not sure – once said, speaking about dance’s long struggle to free itself from that prejudice, “Dance must have achieved that respectable status in order for someone like Michael Clark to come along who wants to make it about sex again.” I mean, even with Merce Cunningham, dance could never be about sex. I remember at the summer workshop he was giving with John Cage, which I attended as a teenager, John and Merce were very much like, “Anything to do with sexuality is beneath art.” The goal was to rise above sex in order to express something that was art. I thought that was silly. I mean, Merce and John were boyfriends after all!

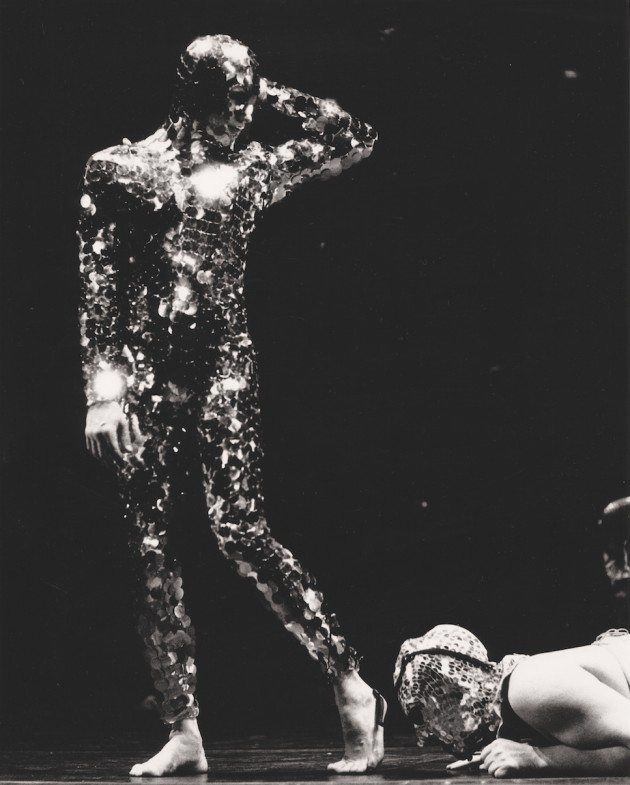

Is it difficult for you now to not be on stage and see the members of your company do what you used to do yourself? In animal / vegetable / mineral you still have a short guest appearance, not really dancing, but walking across the stage doing hand gestures.

It’s a cameo, I guess. So far, animal / vegetable / mineral is the piece with the least me in it. I’m 52 now, I’m limited physically, but I can’t really let go of dancing yet. The dancers in my company are amazing people with the facility to do a whole range of things. Most of them could have chosen to be very good ballet dancers, but they’ve chosen to do this work with me, which I’m very happy about. But I still have to develop my new material with my own body, because I don’t understand it unless I do it myself. I can’t just sit in a chair and choreograph, telling people what to do. And if I wanted to, I could still do something amazing on stage tonight. But I’ve got to be a bit realistic. I wouldn’t be able to walk tomorrow, because of my knee.

You’ve had an injury?

Five. I’ve got to be careful. Operations are not something you should do lightly. If I had another knee operation, it would be to change the entire shape of my legs, and that would be too extreme. Actually, I came to Germany the first time I was diagnosed. The doctor I went to is quite famous apparently. I think his name is Wohlfahrt.

Dr. Müller-Wohlfahrt, the doctor of the German national football team?

That’s him! I first went to him, and then I had surgery at a private clinic in Switzerland. An anonymous art collector and a gallery in London paid for it all. It was this art world thing. I couldn’t have afforded it otherwise.

You and your company seem to receive quite a lot of support from the art world, more so than from the dance world. Why do you think that is?

Well, it’s partly because of my arrogance. I’m not someone who’s involved in the dance world. I don’t go out and see other dance. I think it’s all shit – that’s my attitude. There’s enough dance in the street for me to be inspired by. Also, I hate critics and I don’t want to be their friend. I would find it compromising to them if I became friendly with them. Critics have to be able to say what they really mean, so I steer clear of that. And concerning the support from the art world, I guess artists can sort of relate to what I do. They are struggling to make art something vital. They try to make something that’s dead ultimately alive. And, in a way, I’ve tried to do something similar.

Your list of supporters reads quite impressively – Peter Doig, Tracey Emin, Damien Hirst, Douglas Gordon, Sarah Lucas, Elizabeth Peyton, Juergen Teller, Wolfgang Tillmans, among others. In 2006, there was an auction at Christie’s with works that these artists had donated for the benefit of your company.

I really can’t thank these people enough for their generosity. It’s unfortunate that the subsidies for the arts in England are becoming less and less. Well, since 2005, my company is a resident company at the Barbican Centre in London, but that only means they provide us with an office and put some money into my productions. We’re still struggling financially, and the Barbican doesn’t really have rehearsal space for us. I myself can go in there during the night to rehearse, but not officially, and only by myself. So finding a proper base is what we’re working towards.

Alledgedly it was also an artist, Sarah Lucas, who helped you overcome your biggest crisis. Between 1994 and 1998 you had disappeared from London and were living back with your mother in Scotland. Your company didn’t exist during that time.

I call them my “wilderness years.” I know it’s stupid, but I took my art a bit too seriously and thought I couldn’t make a solo to “Heroin” by the Velvet Underground unless I became a heroin addict myself. It would have seemed disingenuous to me otherwise. I guess that’s just my method approach. So yeah, I kind of got myself addicted, but I had no idea it was going to be such a long process to then get off again.

What it does it feel like to dance on heroin?

Well, ultimately the drug led to me falling asleep on stage – and there’s not much more I can say about it. At first, I found it very creative, but part of that was just psychological. It wasn’t the heroin itself, but the idea that I was on it that got me excited. When I was working on a choreography, I would do a three-day period where I’d use it and then I’d be clean for two days. So, at day three, I’d look at what I’d made and try to be objective. It was silly.

Is it true that, after your rehab and your return to London, you worked in Sarah Lucas’s studio for a while, helping her glue cigarettes on the famous cigarette sculptures she made in the late 90s and early 00s? Cigarette Jesus, cigarette toilet, cigarette garden gnome…

I was on the Dole back then. I had no money and was living with Sarah for a while, dreading to go back into dance – which is ridiculous, because I love what I do. But yeah, I was helping her in her studio, sticking cigarettes on things for her. I was terrible at it. And then she helped me overcome my artist’s block. I guess she had a period of not showing work for quite a time herself, and that’s quite hard, so she knew my situation. She told me, “Oh, why don’t you just go in and make the worst thing you possibly could and see how that turns out?” And it really worked!

animal / vegetable / mineral receives nothing but praise. The Guardian called the piece “transfixing,” the Independent praised its “focused excercises” for their “punk flourish.” Do you keep getting better as a choreographer over the years?

I hope so! I guess I’d like there to be something profound going on. As one gets older, one wants to achieve a certain depth, you know? Dance is an interesting form when it comes to age, because it is a relatively young form in comparison to other arts, and it’s practiced mostly by young people. A lot of dancers burn brightly, but getting older in dance can be difficult. I have to think of T. S. Eliot. In my opinion, he wrote his best work towards the end of his life. One would like to think that’s possible in dance, too.

Credits

- Interview: JAN KEDVES