ROTHSTAUFFENBERG: Give him a mask and he’ll tell you the truth

|Victoria Camblin

How two Germans went to Mozambique with a suitcase full of masks and directed a period tragicomedy, threw a masquerade ball, provoked a riot, and interviewed a North Korean film director in Africa’s luxury hotel that never was.

When Christopher Roth and Franz Stauffenberg packed up their film equipment and traveled to Beira, Mozambique last year, two things were certain: the first was that they would not make a documentary; the other was that Mozart would somehow be involved.

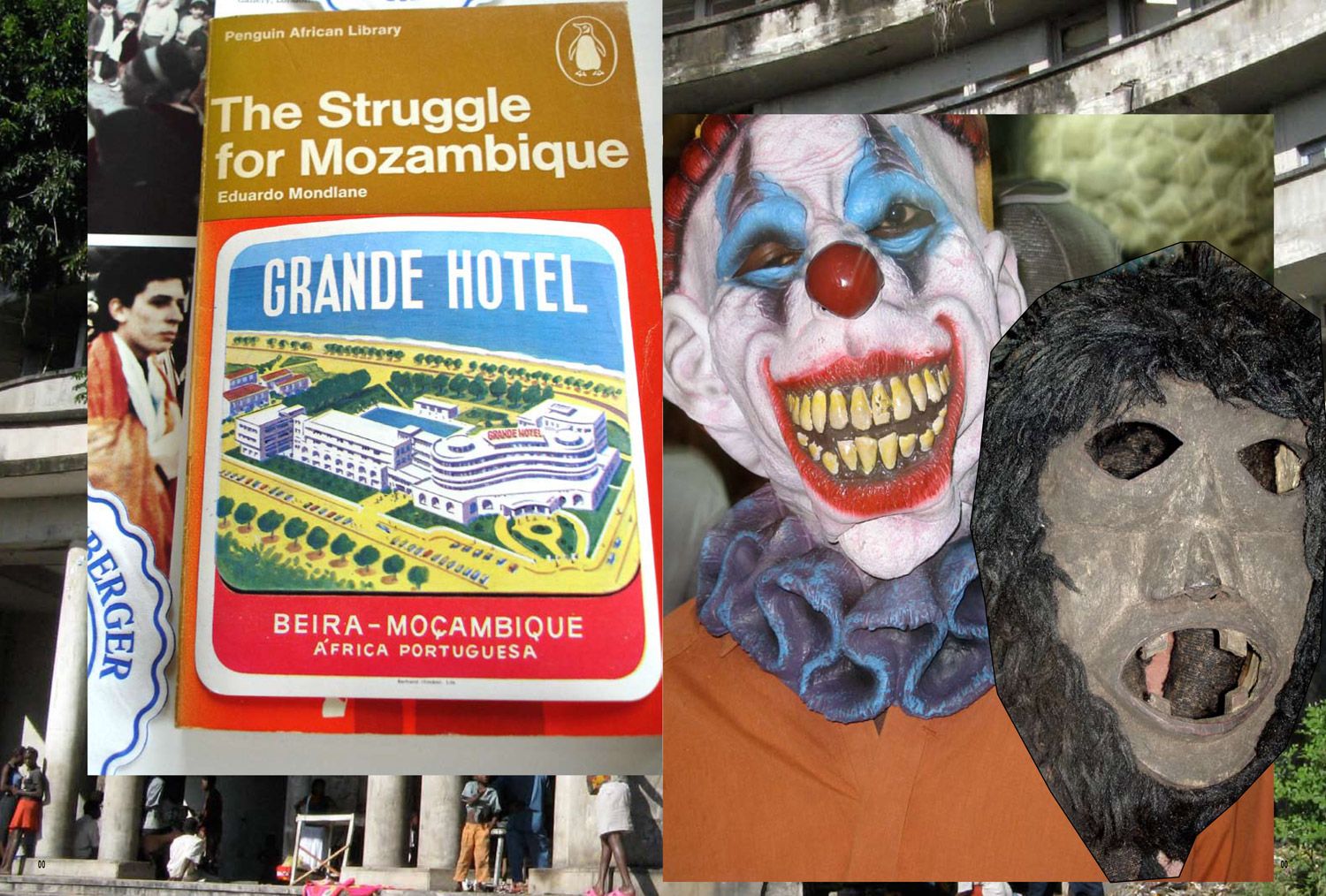

To take care of the first criteria, the two Berlin-based artists, who together form the video/media/installation duo RothStauffenberg, made a pit-stop at a costume supply store before taking off and picked up a suitcase worth of masks – among them a scary clown, a bunny, a Frankenstein, an orange Johnny Rotten wig, and a Boss Nass – the Gungan leader from Star Wars: Episode I. Perhaps the masks were necessary precisely because where they were going – to a luxury 1950s beachside hotel “tragically” turned squat, a colonialist’s worst nightmare come true – was such prime material for a hardcore exposé in the first place. And what better antithesis to making a documentary than to stage a masquerade?

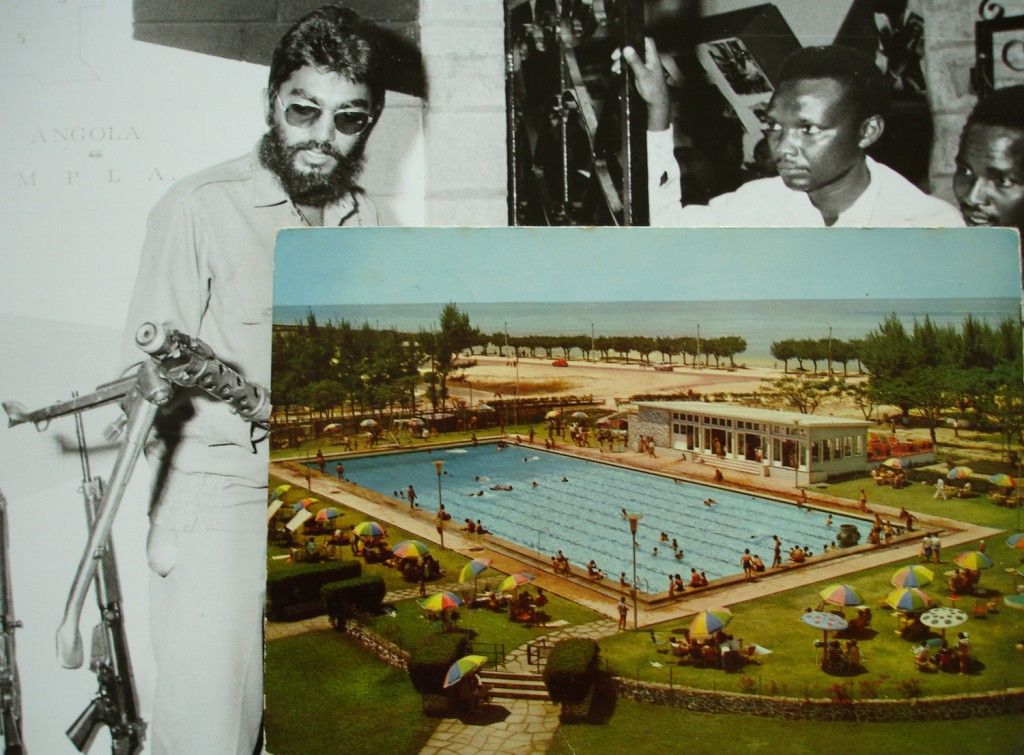

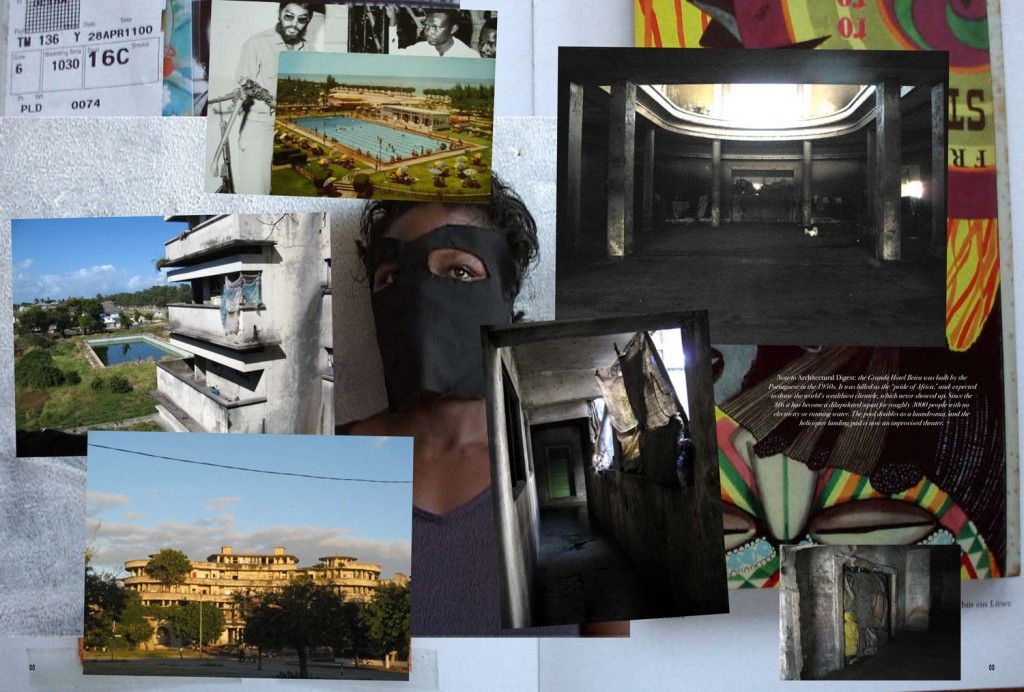

The Grande Hotel Beira opened in 1952; built by the Portuguese, the luxury complex was billed as the “pride of Africa.” But the continent’s would-be most exquisite hotel failed to attract the wealthy clientele it had anticipated. It was closed in the early ’60s and slowly taken over for official use – as housing for prisoners, living quarters for police and army officers, and conference facilities. Following a New Year’s Eve party in 1980–81, with Mozambique still in the midst of a devastating civil war, the general population began to occupy the building; now, roughly 3,000 people live there with no electricity or running water. The old swimming pool now doubles as a laundromat. Roth heard about the Grande from a friend of his who had been working as a physician in the disease-afflicted area – you find typhus, malaria, and AIDS there, and therein lies its tragedy, ostensibly. As RothStauffenberg found, though, the hotel inhabitants also have a resident Mother of Culture who oversees dancing and musical activities, and an on-site theater brigade that performs semi-improvised satirical plays for an audience on the Grande’s former helicopter launch pad.

As I sat with Roth at a café in Berlin-Mitte’s Monbijouplatz and he gestured in the direction of the costume shop where he and Stauffenberg had purchased the masks – somewhere cheesy around Oranienburger Tor – I wondered what clue they had come across in their research that led them to believe that bringing props to Mozambique would be a productive cinematic venture. Surely some specific detail in RothStauffenberg’s critical repertoire occasioned the light bulb moment that convinced them that the masks were a sure thing. Or perhaps it was something in one of the paperbacks I had seen lying around Roth’s Auguststrasse home library when I went there to view footage from the Grande – a library so perfectly thorough and somehow so perfectly German, not in its authorial origins so much as its general culture and hearty theoretical scope. But as well-read a collective as RothStauffenberg is when it comes to cultural history – it bears mentioning that Stauffenberg is a relative of Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg, the German aristocrat who led the failed 1944 plot to assassinate Hitler and who is portrayed by Tom Cruise in Valkyrie – there doesn’t seem to have been an exact precedent. The move was borne more from a spontaneous constellation of influences than from anything so precise. “We didn’t really know what was going to happen,” Roth – who goes by “Bobby” – told me when I asked him if anyone thought it strange when two Berliners descended on their fortress of a residence, distributed masks, and started following everyone around, filming them. “But they never asked why, they never asked what the film was for or when they could see it. They were not interested in it being archived – only in what to do with the masks.”

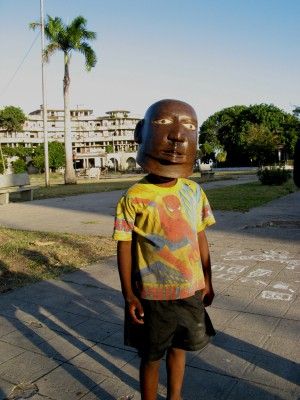

A collection of masks now lives in Roth’s apartment, on top of the books. Bobby tentatively tried one on – a Makondan helmet-mask designed to sit on top of the head rather than cover up the face, the kind you see in RothStauffenberg’s stills on a teen from the Grande who’s also wearing an oversized Gucci T-shirt. “Masks are always so negative in the West; they cancel out the identity of the wearer,” he noted as he replaced the mask next to a copy of Harry G. West’s Kupilikula: Governance and the Invisible Realm in Mozambique, a historical ethnography of sorcery under and since the country’s FRELIMO socialist government. “But in Africa, they channel instead of conceal: you become whatever character inhabits the mask. And masks,” he added, quoting German novelist Hubert Fichte, “must be danced.”

Give a Scream mask to one person and then pass it along to someone else, and a Makondan, says Roth, “will tell you they’re becoming the same character.” Keeping this in mind as the masks circulate through RothStauffenberg’s cast heightens an already palpable absurdist humor in the work: one moment a black Boss Nass sits at his kitchen table grumbling, “I will leave, because I am tired of you all”; the next moment Boss Nass is back, but he’s white and playing the part of a news anchor, holding a large microphone and pontificating in front of piles of rubble near the Grande. In other scenes both Roth and Stauffenberg can be spotted on camera wearing oversized plastic Elvis-style wigs in primary colors while operating a boom mic, plastic wigs that pop up in all manner of domestic scenes at the Grande.

RothStauffenberg brought along a mask for every decade since the hotel’s inception (the ’50s greaser, the ’70s Johnny Rotten, the ’90s Screamer), adding to the collapsed sense of time and space that is inhabited there. The Grande is 50 years of African – even global – history mashed into simultaneous existence: Western Europe’s colonies fold as new countries look east of the Iron Curtain for political models; civil wars ensue and poverty sets in as the Cold War comes to an end and a three-times-removed pop culture floods an otherwise drought-afflicted landscape. But these individual influences have been internalized somehow, filed away into the Grande’s greater subconscious to reemerge, for instance, in the residents’ mini-performances. In one skit, a youngish, slim actor dons a tie and a collared shirt, which he stuffs with a big pillow, paints his face with white facial hair, and rolls up one of his pant legs to play the part of a (presumably white), rotund schoolteacher. Regarding this spot-on interpretation of teachers he encountered in his own schooling, Roth imagines: “Perhaps he was referring to something he didn’t know about anymore – this image of the dorky professor with his pant leg always rolled up from cycling to school was just somehow in his psyche.”

RothStauffenberg’s work certainly deals with disinterring the unseen, pitting the there against the not there. And perhaps to stir the unseen out of their footage from the Grande Hotel, they’ve spliced in supplementary materials. Excerpts from Brazilian telenovelas are interspersed throughout the film; it’s what they watch in Mozambique and a kind of double-removal from the reality of the Grande: melodramatic white people from one not-so-white former Portuguese colony being broadcast into another, less white, more recently independent one. They’ve included softcore Brazilian porn, complete with girl-on-girl masked wrestling matches. There are newsreels and speeches given by former Mozambique President Samora Machel and original voice recordings of Martin Heidegger, both speaking in their own terms about the shaping of images – RothStauffenberg’s goal being to do precisely that with this film.

VICTORIA CAMBLIN: You mentioned that nobody in Beira was interested in the film product, the archive. But Maputo does have a central film archive – you have the Dockanema Documentary Film Festival, the makeshift cinémathèques in huts with flat screens … there’s a certain film tradition there.

CHRISTOPHER ROTH: Jean Rouch, Ruy Guerra, and Godard were all invited by Samora Machel in the ’60s and ’70s – there was a genuine film industry there; they built a genuine film institute. And Machel had established a weekly newsreel program, Kuxa Kanema, which they would show on 35mm in cinemas and on 16mm in these mobile units. But it wasn’t so much for entertainment – it was about education. Machel’s socialist man is built by education – it’s not colonial, not socialist; it’s educational.

Of course eventually South Africa began supporting the anti-communist RENAMO rebel opposition and Mozambique was becoming increasingly isolated and broken. The Yugoslavians started coming in to shoot anti-imperialist propaganda films with bad RENAMOs and good FRELIMOs, I believe it was called The Time of the Leopard.

In some post-Soviet states, say Russia, I feel like Marx and Lenin still preside. Of course in the former East Germany you have squares named for socialist party heroes and streets named for Karl Marx, but it’s not quite the same – there you still have the statues, the marble reliefs, the busts … but what’s the iconography like in Mozambique? Is the imagery still there?

No Lenin, no Mao. But where the USSR had a hammer and sickle, and the Germans a hammer and compass – the Germans being so intellectual – Mozambique has a machine gun and a hoe. Though there is a big Coca-Cola bottle in a square in Beira. Maybe that’s where Lenin was.

They’re not mutually exclusive images anymore, though. In Eastern Europe you can see an ad for some Turkish beer – like Efes Pilsner – screening down the side of an office tower block from the steps of some Stalinist monument.

In Mozambique it’s the phone companies – they’ll paint entire houses with the colors of the phone company, so they’re vaguely corporately branded. The old market hall in Beira is painted blue and green for some phone company.

Another thing you have in Mozambique are these chairs lying all around – on the street, outside warehouses, next to cars. I thought perhaps they were for guards – because there isn’t a public security infrastructure, if you don’t want something stolen you have to find some guy to watch it. But there’s never anybody sitting in these chairs. I don’t even know where they get them.

So you have streets equally named after Lenin and Mao, Kim Jong-il and Karl Marx, then everything’s in Portuguese, like this crazy cultural palimpsest about to rupture – or rather, post-rupture …

It’s at a geopolitically tragic crossroads. [Bobby grabs my pen and paper and draws a map of southern Africa, with Mozambique and its neighbors – Tanzania, Malawi, Zambia to the northwest, Zimbabwe to the west, and South Africa to the south. He draws arrows and scribbles across troubled borders.] You have people shooting their neighbors to prevent migrations; rich people vacation there but only on the islands – they won’t go near the mainland. Samora is the glue that holds their identity together, he’s a hero – the only other one is Mandela, who’s now married to Machel’s ex-wife, Graça. They live on Rua Friedrich Engels in Maputo – speaking of interesting crossovers.

But RothStauffenberg’s not interested in tragedy.

No, we’re not – we didn’t go to the Grande to say, “See how bad it all is.” It’s apparently quite prestigious housing in fact. We’re interested in cultural clashes, not melancholy. We’re interested in the civil war, but as an image, and we’re not interested in creating tragic drama. That’s why we use Mozart – the non-melancholic composer.

As Mozart’s “Ora pro nobis Deum” climaxes RothStauffenberg’s camera follows a masked, pre-teenage couple, holding hands as they guide us through the maze of the Grande like narrators in a comic opera. Cut to a group of wigged women dancing, and suddenly we’re at court in Versailles – one woman’s wig is even white, as though channeling a modified Marie Antoinette. One girl’s shirt says “Paris” on it; another girl wears a decorated pareo in such a way that a picture of John Paul II falls directly over her backside, like a Papal bustle. So come together more or less all the necessary ingredients for an impromptu production of The Barber of Seville.

Of course the masquerade RothStauffenberg organized once they had finished filming at the Grande doesn’t quite fit into the Grand Siècle adaptations we’re used to – it quickly descended into a riot when they ran out of beer and the small crew had to flee, the designated security guards mean while preoccupied with protecting their own booze. They even got a “go back to your country” or two. And instead of a Figaro, RothStauffenberg gives us Shin Jun-chul, a legendary 71-year-old North Korean film director who has been living in Mozambique on and off since the 1970s. Shin, a kind of people’s maverick, comes into the story of the Grande like a deus ex machina to sanction, enhance, and contextualize RothStauffenberg’s work there. The artists interview him, three times in Mozambique and once in Berlin, and produce Based on a True Story, a simultaneous catalog of their own work and of Shin’s – save for a handful of celluloid negatives, the director’s body of films has entirely disappeared. Those that he finished were either destroyed by order of Kim Jong-il or by fire, when the fiction (not fictional, though perhaps it might as well be) section of the INAC (National Film Institute) burned down a few years ago – or they are simply lost in the infinite archives of rusting film cans from Maputo to Hanoi.

How did you ever come to find Shin Jun-chul? You hear these fantastical rumors of his having vanished under suspicious circumstances or that he’s been living in exile or maybe he is dead – died in a plane crash like Samora Machel, all his films destroyed with him … I actually heard that at the film archive in Moscow they have him down as deceased in 1986, the same year as Machel.

Perhaps that’s when he died for the Soviets and they never updated the data? It’s interesting because Shin was actually living in Mozambique for a decade and in 1986, after Machel’s death, he flew to Vietnam for a few years and shot a couple of films there. In the ’90s he met the sound engineer Martin Müller in Havana …

Was Müller there working on Buena Vista Social Club?

He was initially, but it was actually Oliver Stone who put him in touch with Shin – Müller met Stone in Cuba; Stone turned out to be a close friend of Shin’s, and Shin had been looking for someone to work with him on a film called Harare, which of course hasn’t been made yet. So Stone suggested Martin, and he was able to put us in touch with Shin, whose films we had unsuccessfully searched for at the National Film Institute in Maputo while we were there. Of course, Shin can’t even access them – the people taking care of the archives just sort of stand around waiting for funding while the celluloid decays around them, wearing masks to protect themselves from the harmful fumes.

And we’re back to masks again. Only this time they seem quite negative, quite shield-like.

Though not very good shields I imagine, if what they say about decomposing celluloid is true. But it’s the ultimate post-Marxist dramatization: they’ve received funds from UNESCO and two million dollars from Portugal, but they’re still in this entropic state, slowly breathing in this melting archive through flimsy masks while holding out for the big bucks so that they can pocket half.

So you have this fantastic but inaccessible film archive and its fantastic-ness is solely conveyed by these masks – the masks demonstrating the tragedy of its destruction and hence, the value of its contents … the work becomes all the more compelling in its non-existence and they don’t even need the images to tell this story.

But we do have images, we do have stills from Shin’s films. We have titles, dates, locations, contexts, and that’s the very existence of Shin’s oeuvre: you take all these elements, and you build one picture in the end. Interestingly, it’s also how our film about Mozambique is built – and that of course hasn’t been destroyed! It’s also a way of approaching Mozambique in images and it’s how we presented the book, Based on a True Story.

The interview is so much about, well, truth and fiction, or maybe the interweaving of reality and fantasy – that’s certainly one tradition of the masquerade, the idea that you can enact fantasies if you’re masked, à la Eyes Wide Shut. Walter Benjamin talked about how the camera introduces us to unconscious optics just like psychoanalysis introduces us to unconscious impulses. And here you are, two Europeans with cameras and masks, and you have a masquerade 30 years after colonialism – it’s at least a triple-whammy.

Well you need a trained eye, no? You need a trained eye to see the images behind the matrix, you need a trained mind to access the unconscious …

There’s a definite Surrealist undercurrent in all this – the unfortunately not so out-of-date notion of the hysterical female, the unknown origins of all these cultural influences …

You know the Surrealist Michel Leiris wrote about this. In our interview with Shin we spoke about how, as an ethnologist, Leiris would build stages on which he would later perform, and how in L’Afrique Fantôme, he actually stole masks from villagers in Mali. It might have been a scandal, but in a sense Leiris’ way of engaging was by stealing the masks. We engaged by giving them out.

“Give a man a mask,” said Oscar Wilde, “and he’ll tell you the truth.” The idea that humans are paradoxically more truthful, or at least less inhibited, when they are masked – or otherwise made anonymous, like in the confessional booth or blacked-out with their voices altered on crime exposé TV programs – only really applies when truth is what you’re after, or if you’re coming from somewhere inhibited in the first place. So if, like RothStauffenberg, you’re not after hidden facts or uncovering whatever primal honesties we’re all supposed to be harboring, there’s a lot more you can do with a mask.

Credits

- Text: Victoria Camblin