Like it Never Happened: An “IN MEMORIAM” by Architect REINIER DE GRAAF of OMA

In the recently published book Four Walls and a Roof – The Complex Nature of a Simple Profession, Reinier de Graaf reflects on what it means to be an architect today. De Graaf himself is a partner in the Dutch architectural firm OMA, which has been featured frequently over the past decade by 032c, most recently for their Prada runway set designs. The book’s essays are made up of his personal accounts, disappointments, analyses of architecture’s connection to political and economic movements as well as a 31-page photo essay titled “In Memoriam.”

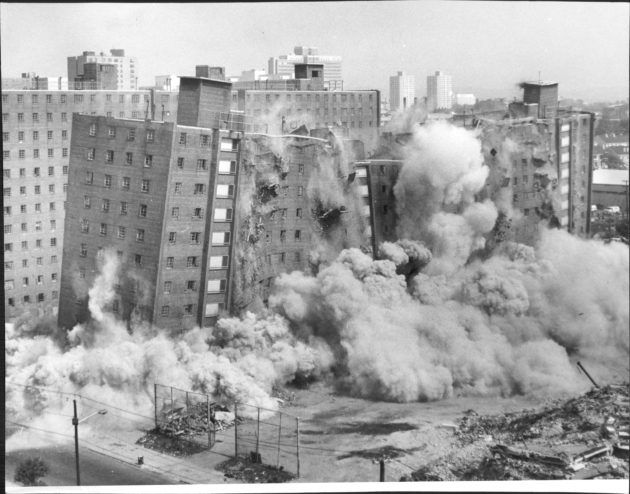

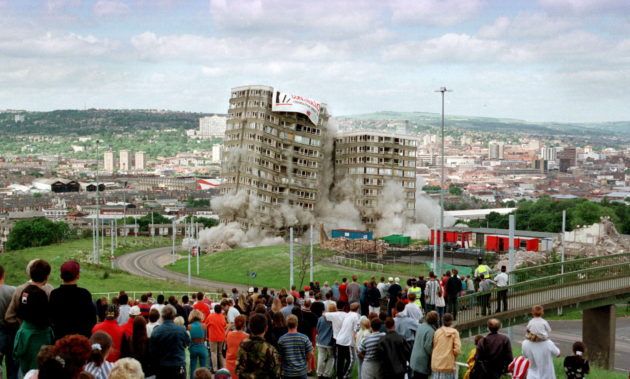

“In Memoriam” mirrors the messiness that comes with a shift in cultural values. Pictured below, the photographs show exploding post-war social housing. At the moment of their collapse, the once affixed structures freeze in wobbly uncertainty. It hurts to watch an idea be demolished.

In anticipation of the Berlin book event held at the ANCB on January 31st for Four Walls and a Roof, 032c’s Eva Kelley spoke with Reinier de Graaf about a building’s life cycle, if we have simply stopped trying, and what our architecture says about our attitudes.

EVA KELLEY: Could you tell me a bit about the photos in “In Memoriam”? What does this collection of images mean to you?

REINIER DE GRAAF: To me, these images represent a larger point, namely the loss of certain progressive values. Nearly twenty years into the new millennium it is as though the previous century never happened. Its low-cost industrial architecture, which facilitated social mobility on an unprecedented scale, is now discredited. Despite higher rates of homelessness, large public housing estates are being demolished with increasing resolve. The idea that the twentieth century with all its great emancipatory achievements is slowly being undone seems to find concrete proof in the removal of its physical substance.

Are buildings that get demolished a “failure” of architecture? Or do you see these images as part of a natural life-cycle?

These buildings were demolished well before their natural life cycle ended. Somehow, society felt it no longer had a need for them – not because their mission had been accomplished, but rather, because we gave up on their mission. To me, it is an open question if it is really the architecture that has “failed” or whether the demolition of these buildings ultimately sounds the death knell of political ambitions – that when it comes to progressing in solidarity, we have simply stopped trying.

I recently went to a talk in which the state of Rome was discussed – how the trash was piling up and money was only flowing into the upkeep of tourist attractions rather than taking care of its citizens. One panel member suggested that maybe one should accept that Rome would inevitably turn into a museum and that it might be ok that some places become Disneyland versions of themselves. Another panel member was outraged at this sober reaction and suggested a cap on tourism. Do you think architecture should shape society or should the people’s desires shape architecture?

Of course, architecture is a response to people’s needs, but in themselves those needs never explain the full story. The needs of people can be presumed to be fairly consistent. If it were solely people’s needs that shaped architecture, we wouldn’t see the shifts in style or approach that we see happening in architecture. Architecture is largely a reflection of the type of society we choose to have. In that sense the demolition of these buildings is as much an ideological statement as their one-time erection.

Is there a tipping point to this relationship?

The relation between people and society is by definition reciprocal. The same goes for architecture. The essence of reciprocity is that it has no tipping point.

Four Walls and a Roof – The Complex Nature of a Simple Profession is published by Harvard University Press (Cambridge, 2017).

Credits

- Text: EVA KELLEY

- Photographs: Courtesy of OMA and Harvard University Press