Family Photos: Film premiere looks back at Drawing a Blank, 22 Rue de Lubeck, Paris 16ème

|Octavia Bürgel

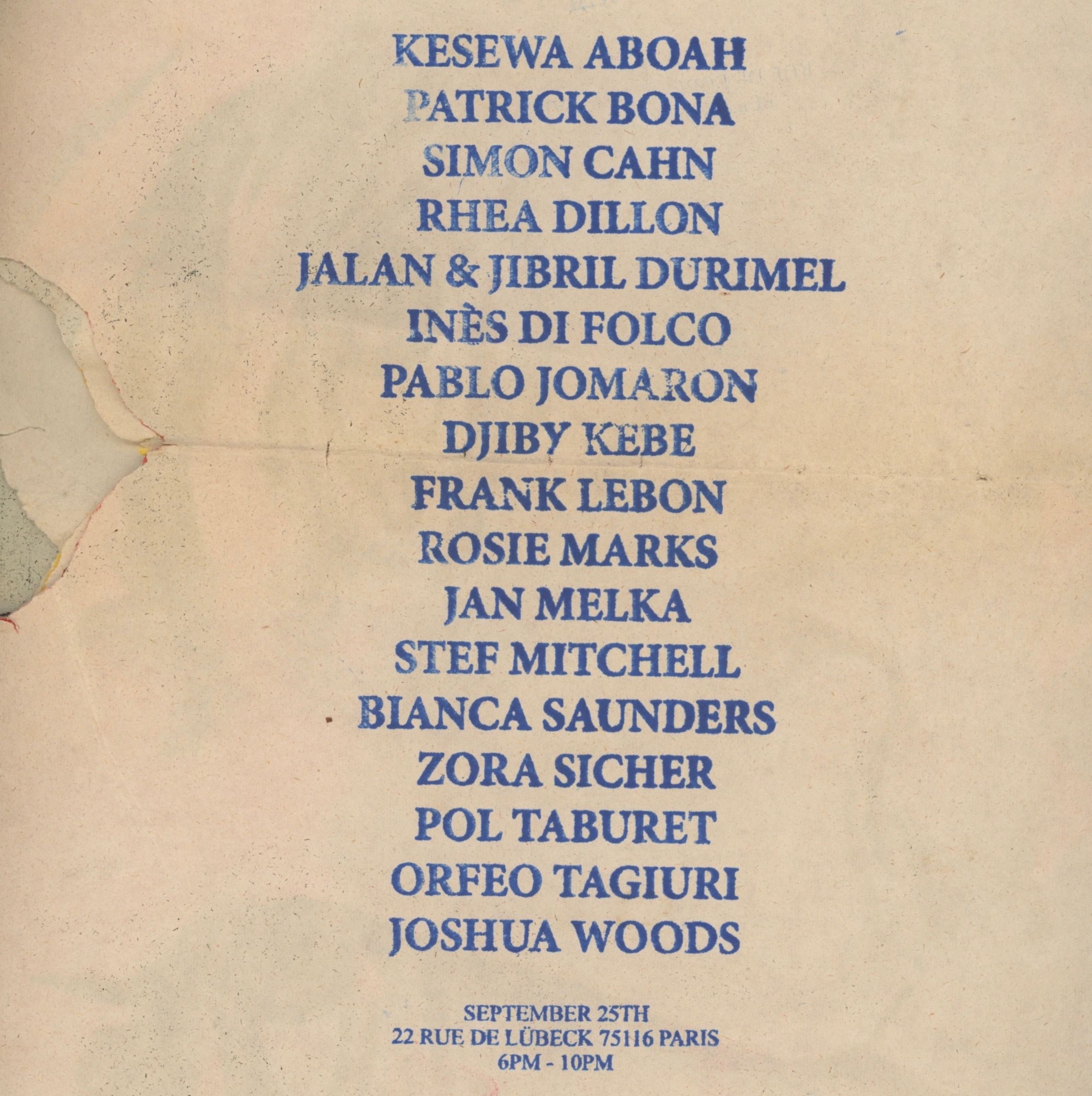

As we enter this strange holiday season, we’re reflecting on the moments that brought us together in 2020. This past September, during a week that would have ordinarily seen Paris overrun with fashion’s gentry, intrepid mask-wearing art kids and good humored adults made the journey to a hidden garage at 22 Rue de Lubeck. The occasion in question, Drawing a Blank, was the fifth installment of a multi-city, four-years-running exhibition series conceived and curated by Ben Broome. Describing the shows as “D.I.Y. done right,” Broome makes a point to not limit their scope. “I like the idea of promoting potential future collaboration,” he says of the mix of artists and mediums in the show. “I don’t want it to be a ‘photography show’ – I don’t want it to be a ‘painting show.’ I try to cover all the bases.” The events are animated with live performances, which have, over the years, featured Onyx Collective, Princess Nokia, Chassol, Slauson Malone, and Oko Ebombo, among others.

“I pick an artist first and foremost because I like them, I like their attitude to art-making, and I think they’ll fit well among the rabble of other artists involved,” Broome tells me when we recap on the phone. The effort behind the Drawing a Blank shows – which took place in London and New York before this latest installment – stems from Broome’s deep faith in the communal. Fronting his own money, searching out venues and sponsors, attending studio visits and sourcing press coverage are all part of his mission to create a borderless nucleus for his artist friends – one that expands and responds to itself, but remains free from the big-buck consumerism and competition of the capital-A “Art World.” Drawing a Blank exhibits are imbued with the spirit of dedication, collaboration, and learning – and provide a matrix with multiple points of entry for makers of every background to experiment.

D.I.Y. does not mean that the standards are low. Which is why the opening – just days before the city tightened restrictions on social gatherings – was equipped at every entry with security-guarded hand-sanitizing stations and stocks of extra masks. “Every day I would Google: ‘Paris covid news.’ I was checking the numbers. Maybe the show was irresponsible, even with everyone in masks and equipped with hand sanitizer. But I also think people needed an opportunity to cut loose. I’m glad we were able to provide it, legally,” Broome says of the restrictions, which, at that point in the late summer, did not place limits on group size for events on private property. “Collaborative projects and group exhibitions bring people together, and I think that particularly has power now, when the world is so fractured.”

Drawing a Blank’s rhizomatic decentralization means that the party is never truly over, even once the show is closed. Keep scrolling for a new short film by Eli Lawson-Adamah and Ademide Udoma, filmed during the lead-up to the event, alongside surveys of exhibiting artists, Rhea Dillon, Pablo Jomaron, Ines di Folco, and Orfeo Tagiuri, on the 48 hours leading up to the show, how they became involved, and the work they exhibited.

Name: Rhea Dillon

Location: London

Practice: Artist, writer, and poet

Ben sent me the best cold email I’ve ever received. I think it’s rare that people are honest about being fans of your work these days. There’s a lot of ego and hierarchy being absorbed by previous bad institutional practices. I really respected his honesty and sheer eagerness to hear what it is I have to say – or, even better, would like to say. So much energy is brought into the space in a Drawing a Blank exhibition, and it feels very community- and artist-led in that sense. The opportunity to meet the other artists by setting up as well as winding down together was magical.

My energy [that day] felt like a myth. I came on my period the week of install and that sent my sense of self into a grinder. But my friends said I was on top form for the opening so it could have just been my hormonal anxiety creating a false sense of lost self.

I exhibited three pieces that explore the exploitation and expectations of the Black woman: of my inhabited body. A sculpture titled Atlas’ Duppeee Whoopeee Seat: women should stop cleaning faeces, everyone should clean faeces, and Golgotha and Janus *pause* leaking fortified enclaves, two sculptural paintings made specifically for this show. I wanted to create work that defies the form and expectations of the body that produces it.

Janus is the Roman God of the past and future. In my work, I never speak to one singular idea. I approach things with my (cursed) abstract brain and then try to synthesize it for myself and [later] for an audience. That piece came from feeling irritated because I had a big-ish gallery get in touch with me and it felt like they didn’t like any of my work and they just wanted me [as a trifecta]: Blackness, queerness, woman – pinned via crucifixion to the walls. I was thinking about a Zora Neale Hurston quote, where she said “I feel most colored when thrown against a sharp white background.” I read it in terms of the experience of a lot of Black artists in the white walled gallery space now.

During lockdown, I’ve been questioning the Black woman’s access to amorphicity. Thinking through the ideas of crucifixion and Jesus’ shapeshifting; Christianity and colonization’s link. Colonization was enforced through a hyper-Christian overthrowing of any kind of practices that existed. Cultures were “sanitized” through Christianity. In Christian spaces, water is used to create a sanitization that further works alongside the promotion of a postmodern hyper-sanitary space. Who is tasked with sanitizing that space? Most often it’s the Black woman. The Capitalocene is upheld on the backs of Black and brown women workers. When we were clapping every Thursday evening for the NHS, we weren’t seeing the workers. There’s a quote by Françoise Vergés in an essay she did for e-flux last year. She says there’s a phantom body that keeps the white male CEO afloat. That body is the body of a Black or brown worker – the women.

Three is a number I use a lot in my work: it pulls everything together, it makes me think about the triangular trade and about a triple consciousness us diaspora kids now have. The cross [that I exhibited] leaks a slow water drip exploring how middle and upper class spaces are becoming broken up by a deteriorating class system that can’t hold itself up anymore: leaking fortified enclaves. At the end of Vergés՚ essay she asks, “who is going to clean up this mess now?” Somebody has to do that. Should that body be mine because it is my work? Should it be the white male curator? Should it be everyone? Janus becomes its own manifesto. January is named after Janus, the start of a new year. Janus speaks to the start of a new radical future.

Name: Pablo Jomaron

Location: Paris

Practice: Photo, video, …

Ben’s project offers freedom, confidence and love. Before the opening, I was with family and friends, meeting the other artists, feeling good. I felt a bit shy about showing my movie because it is [made from] personal images. It has this strange form because it is a fiction made from my own archives – personal photo and video I made over the last three years. There is a character who is played by my cousin, and there are images that represent his frenetic thoughts. There are many shows I participated in where I did not feel comfortable or at my place. At Drawing a Blank I just felt like me, I was with my friends and people I love.

Name: Ines Di Folco

Location: Paris, Tunis, Havana

Practice: Painting, music

I met Ben in a restaurant. I made him discover “saucisse au couteau,” one of my favorite Parisian dishes. I discovered we could talk about anything and he would always be passionate. His enthusiasm about life is contagious. This exhibition is unique – huge and homey at the same time. It’s a present for the youth in Paris. It’s hard to reunite people, and Ben did it.

I woke up on the day of the opening and summer was gone. I prayed for Ben, and for the rain to stop. It worked. Then I went to see my friend Andrea. She makes incredible fake nails, unique in Paris. I told her I want the color of fire and rainbow at the same time. Then my mom told me not to move because a crazy dude was cutting people with a butcher knife one street away from where I was. I took my baby to my mother’s house and I came to the opening.

“My paintings were alive, moving and beating with the hearts of the people.”

I showed two different works. One shows Tunis at night, and my mom with her sisters. Those three sisters are like three moms to me – they talk for hours when they are together. I wanted to paint them under the moon, in the middle of the jasmine flower perfume and rose geraniums.

The other painting is a boat, and naked people looking at it. It represents the knowledge we appropriate from Indigenous people and slaves. For example, every day we eat and consume plants and products saving our lives without knowing where they come from, or how they arrived to us. It’s good to deconstruct elements of our daily lives because nothing has to be kept secret. The violence has to stop. We should all be Loved, Educated, and Liberated: that’s what I wrote in French on the flag in the painting.

My paintings were hanging in the middle of the party. It was scary because people touched them and crossed under them. But when I think about it now, I say yes! My paintings were alive, moving and beating with the hearts of the people. They, too, are doors. Windows you can touch, cross, and look through from above and from behind.

Name: Orfeo Tagiuri

Location: London

Practice: Mixed/Poetry

I met Ben in London where he put on the first couple of Drawing a Blank exhibitions. He has a fearless knack for approaching anybody and befriending them. You could drop him in any city – he’s a magnet to creative energy. Retrospectively, it makes sense that the first show was birthed out of his friend group, which already included a lot of great artists. In the first venue – a very dilapidated house in Peckham – Duncan Loudon hung an active chainsaw from the ceiling so that it spun circles over people’s heads. The Drawing a Blank spaces are increasingly impressive, but it’s safe to say that Ben has maintained that sense of community, with the potential for something reckless in the mix.

I spent the days leading up to the show inside the exhibition space watching everything come to life. Ben does such a good job of creating a family environment at his shows. I spent time meeting the other artists and getting a glimpse behind the veil of what goes into their work. There were also a couple panic moments when rain waterfalled through the ceiling, into the space.

I showed two paintings of falling angels. One of them is terrified and one is serene. I’m still hoping to hang them out of a tall building at some point. In this way they represent a bridge in my work, from a refined studio or gallery space, to art that thrives in the world outside. Allan Kaprow has this great phrase: “nonart is more art than Art art,” which is to say that no matter the art, it’s never going to be more interesting than a street fight, or the leaves changing color in autumn. That’s been a driving mentality shift for me recently. As an artist, you can offer a lens to someone, to say the track of a tear running down a cheek is a more beautiful mark than any brush will ever make. That perspective is infinite and ubiquitous! In this way, the ultimate role of the artist would be to become redundant in a world where everything is poetry.

Credits

- Text: Octavia Bürgel

- Film: Eli Lawson-Adama

- : Ademide Udoma

- Photography: Octavia Bürgel