“The Earth is Trembling”: ÉDOUARD GLISSANT in conversation with HANS ULRICH OBRIST

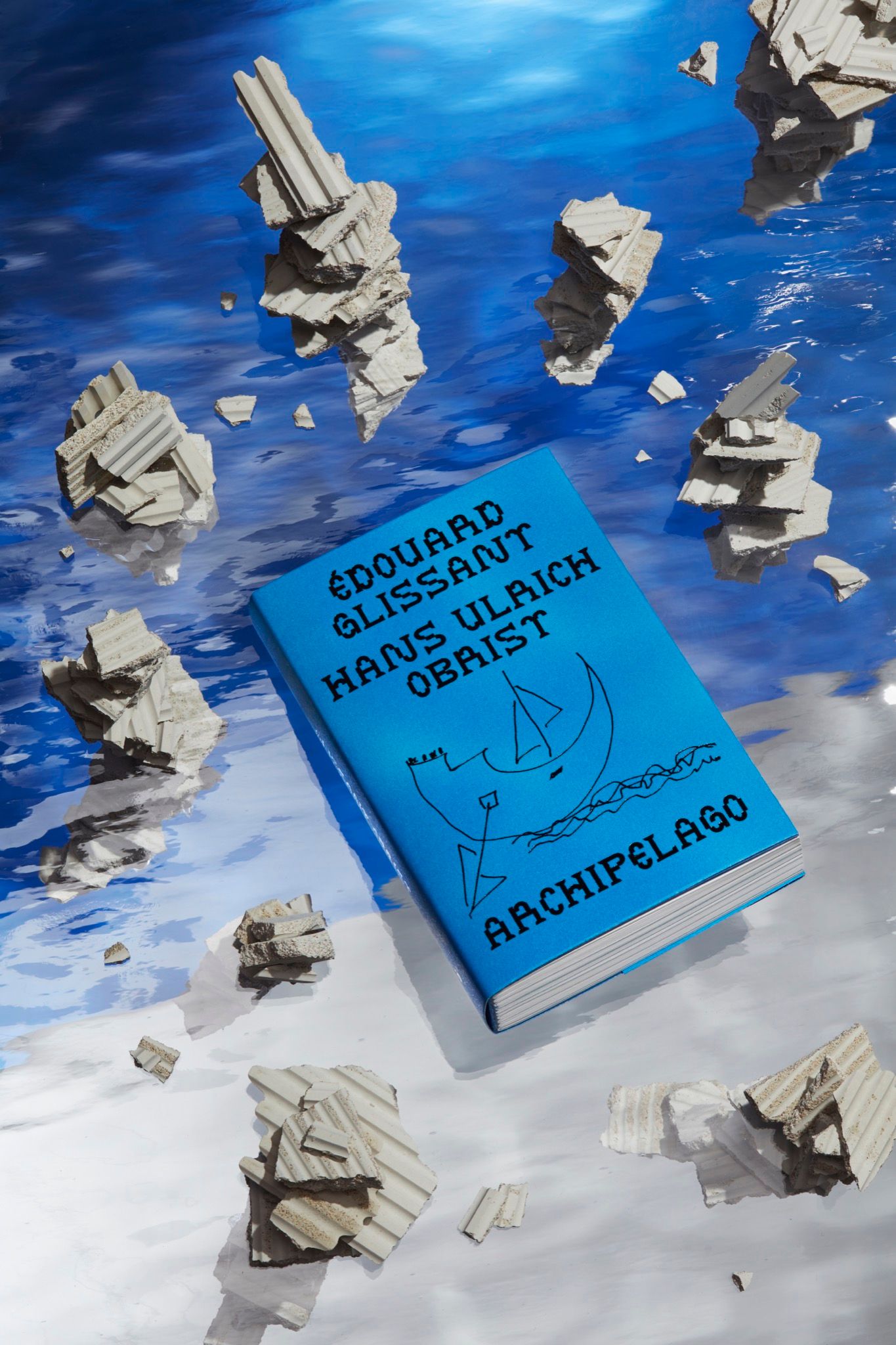

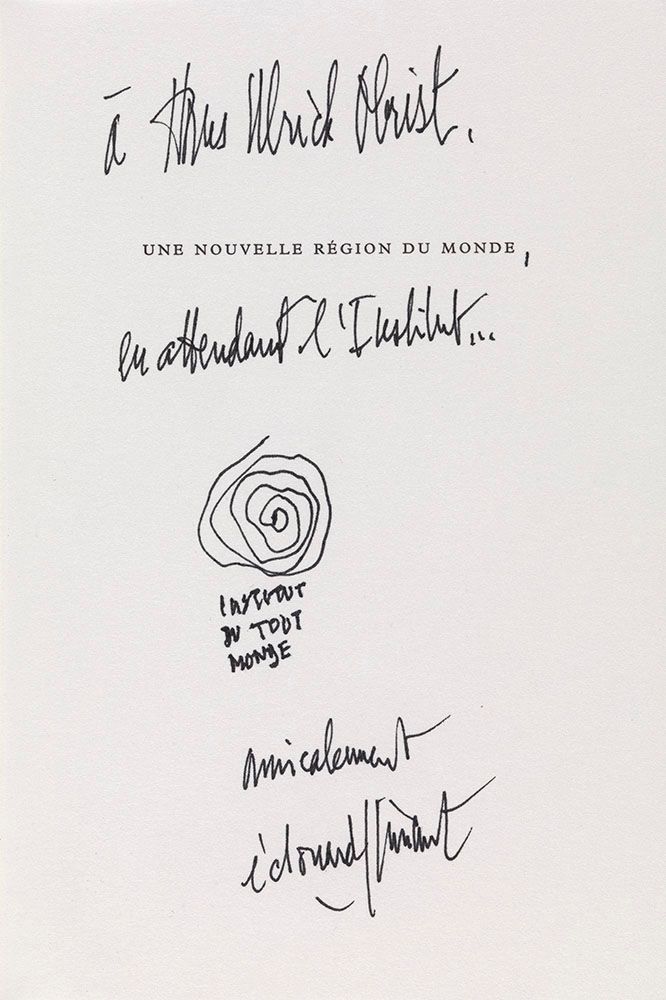

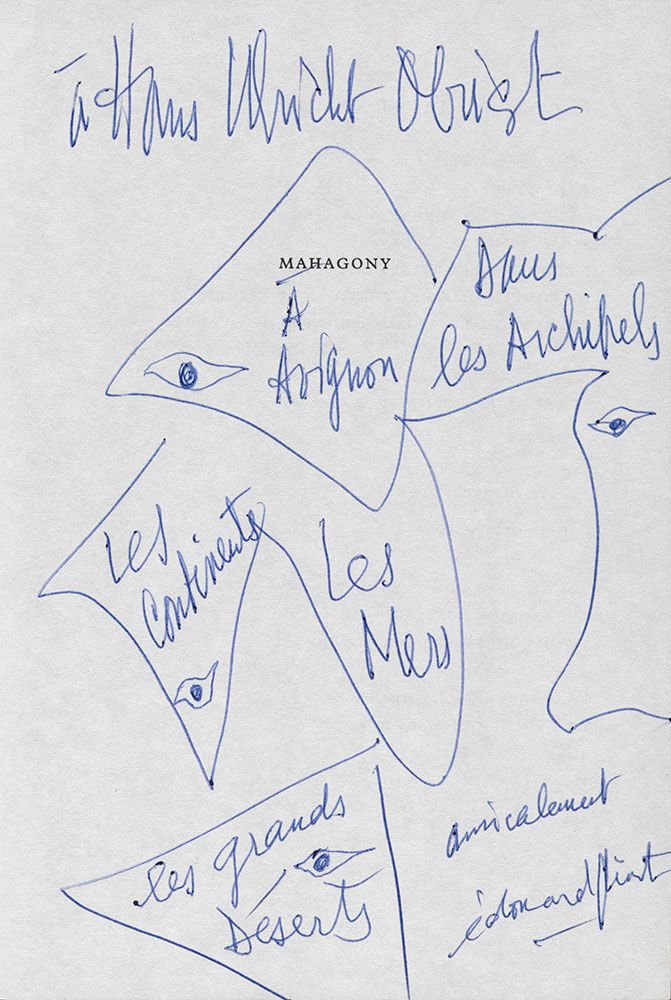

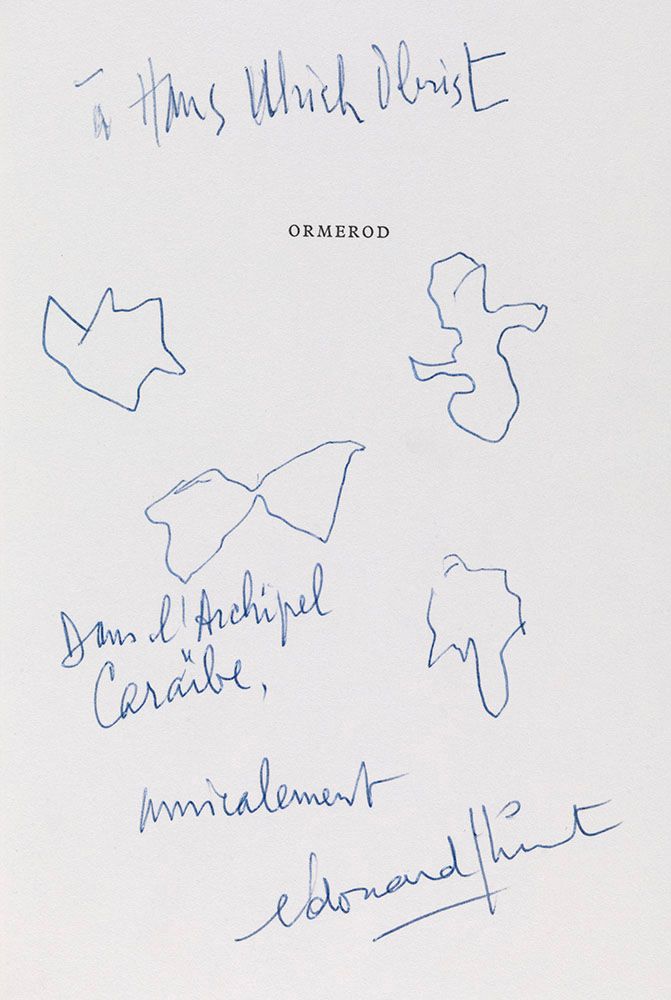

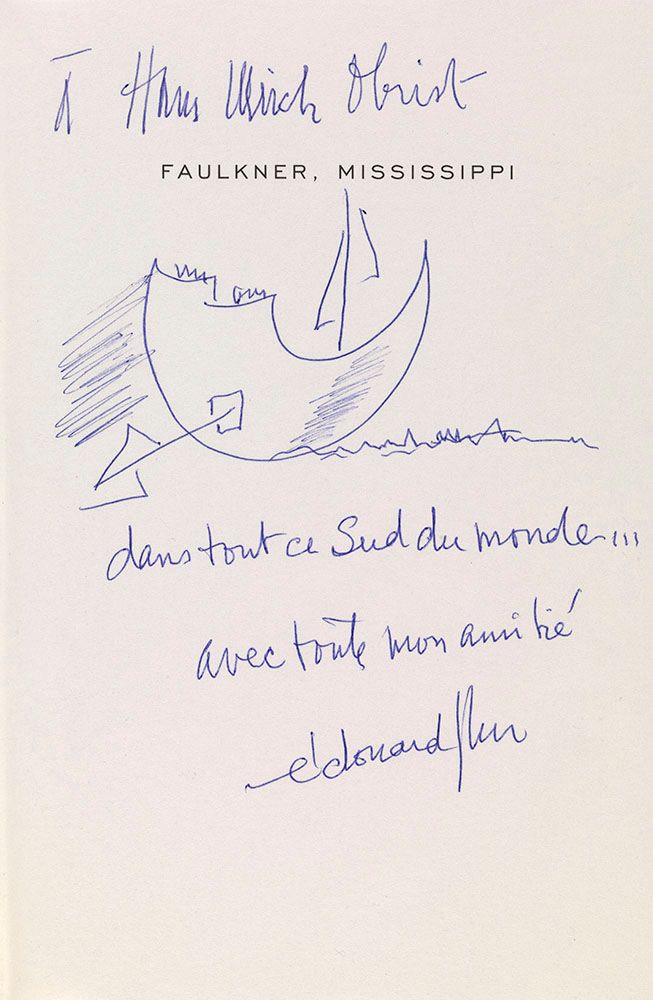

Writer and philosopher Édouard Glissant formulated a succinct motto — almost an affirmation — for those in opposition to the homogenizing effect of globalization: “I can change through exchanging with others, without losing or diluting my sense of self.” This phrase is referenced twice in The Archipelago Conversations, the latest installment in a series of pocket-sized books by ISOLARII, which compiles and arranges the interviews between Glissant and Hans Ulrich Obrist between 1999 and Glissant’s death in 2011.

Though Obrist’s name is also on the cover of The Archipelago Conversations, the effect of the text in form and content is to highlight, first and foremost, Glissant’s school of thought and, secondarily, Obrist as its devoted — almost religious — student. In his brief introduction to the text, Obrist emphasizes Glissant’s outsized influence on his practice, even claiming to study Glissant’s books “each day, every day, for twenty minutes.”

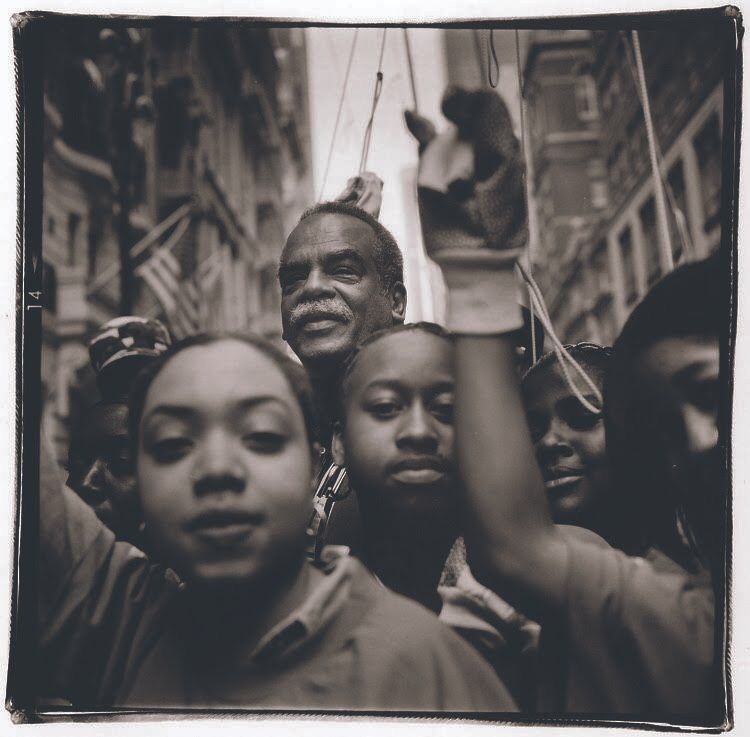

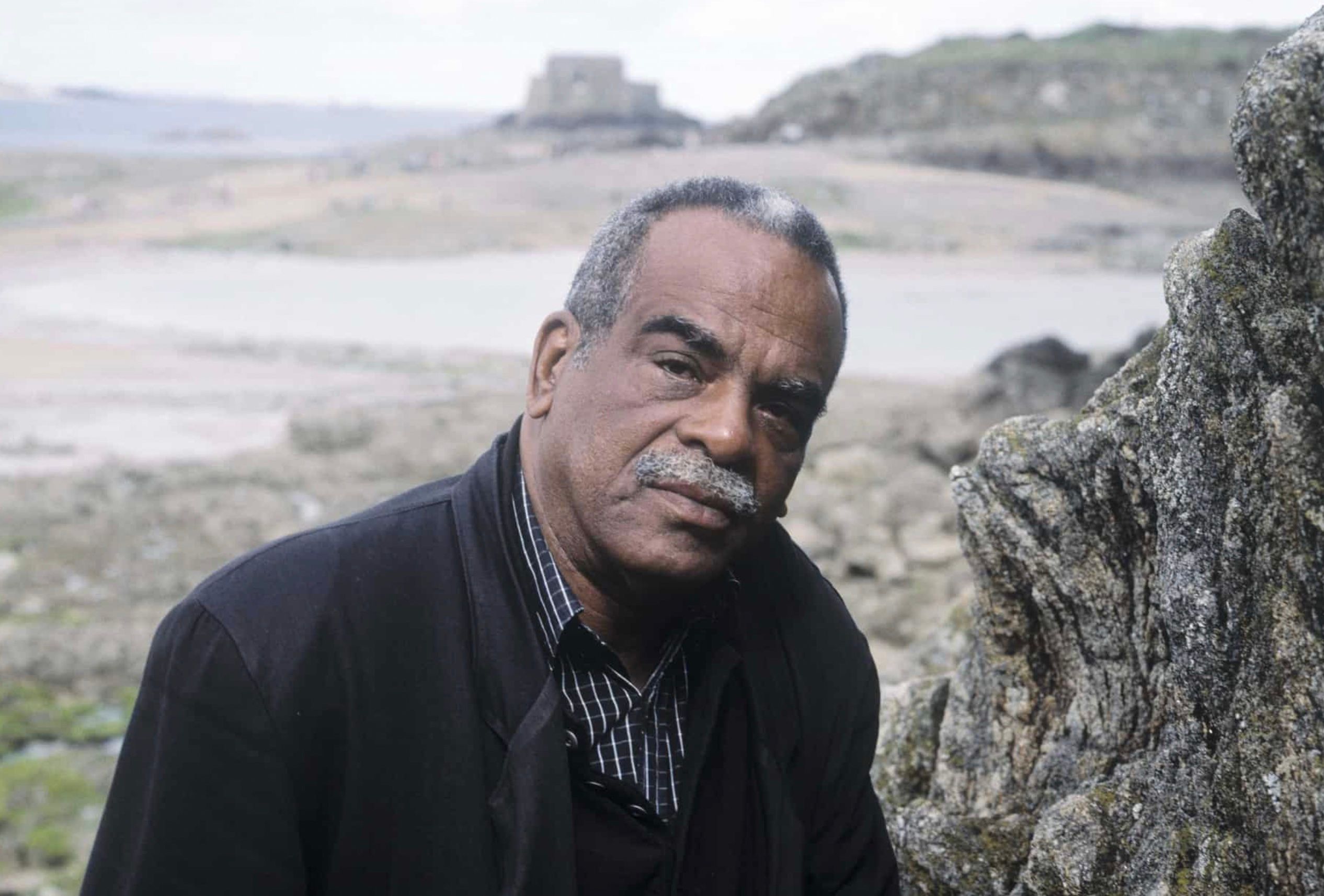

Born in Martinique in 1928, Édouard Glissant was a classmate of seminal theorist Frantz Fanon, then moved to Paris in 1946. Fifteen years later, Glissant’s involvement with French separatist group Front Antillo-Guyanais pour l’Autonomie inspired then-President Charles de Gaulle to bar the writer from leaving the country for four years. After 1965, Glissant lived between Martinique, the US, and France.

Today, some of Glissant’s theory – with its focus on the tenuous relationship between increasing globalization and nationalism, the collective trauma of colonialism and slavery, and the urgent need for hopeful anti-establishment thought – may feel familiar and absolutely contemporary. But at the time, his ideas on archipelagic thinking were revolutionary.

An archipelago, literally, is a cluster of small islands. When Glissant uses the word, he imagines something which exists in opposition to the staid constraints of the continents; which, drifting, “must” encounter the realities of different, foreign places. “The archipelagos of the Mediterranean must encounter the archipelagos of Asia, and the archipelago of the Antilles,” Glissant tells Obrist. As such, these sites are fertile grounds for creolization – Glissant’s utopian descriptor for two different cultures which mix with one another, producing something wholly new. These theories bring up central questions about the construction of identity, memory, and the world we strive to create, all of which are evoked in Glissant’s credo: “I can change through exchanging with others, without losing or diluting my sense of self.”

Could any advice be better suited to this time of omnipresent exchange, when “discourse” reigns but vitriol triumphs? Although the internet – that portal through which foreignness collides – is never mentioned, it’s fascinating to imagine how it’s implicated in Glissant’s project. More directly, this ode to open conversation succinctly typifies The Archipelago Conversations itself, a loving portrait of mutual effect between two of this century’s heavyweight thinkers.

The following interview is an excerpt from The Archipelago Conversations.

Édouard Glissant: The earth is trembling. Systems of thought have been demolished, and there are no more straight paths. There are endless floods, eruptions, earthquakes, fires. Today, the world is unpredictable and in such a world, utopia is necessary. But utopia needs trembling thinking: we cannot discuss utopia with fixed ideas. Because today we are always the object of bombardment, of bombing, of events, news, and so on and so on. We cannot escape that. And we have to manage with that.

Hans Ulrich Obrist: What is trembling thinking?

Tremblement. Firstly, what I call tremblement is neither incertitude nor fear. It is not what paralyzes us. Trembling thinking is the instinctual feeling that we must refuse all categories of fixed and imperial thought. Tremblement is thinking in which we can lose time, lose time searching, in which we can wander and in which we can counter all the systems of terror, domination, and imperialism with the poetics of trembling—it allows us to be in real contact with the world and with the peoples of the world.

For me, that’s what trembling thinking is. An instinct, an intuition of the world that we can’t achieve with imperial thoughts, with thoughts of domination, thoughts of a systematic path toward a truth that we’ve posited in advance. It’s metaphorical, but it’s also real, concrete.

It gives us something that systems of thought cannot give us, not today at least.

Yes. think of the sumptuous ways of Western cultures: Greece, Rome, France, Germany… All their great ideas — Imperialism, Cartesianism, Egalitarianism, Marxism, and Socialism — approached all the people of the world with a confident objective: “I have to do this or that and I will achieve it because I have a system of thought.”

They represented forms of conquest, then, projections that attempted to realize themselves.

They did, they did. But these systems are not the sum total of Western thought. You still have the mystics, you have Ramon Llull, the Cathars, all the philosophers like Friedrich Nietzsche, who stood against those systems of thinking. They remained, and remain still, in the shadows, however. Western cultures are not monolithic; they just haven’t presented their tremblement to the world. They are still guarded.

And so, for me, I had to find trembling thinking by myself, alone — if you are to find tremblement, you have to find it by yourself, because a system of interdependence is conceivable only if you are really independent in your own mind, if you do not prescribe to a system of thought

So we have to find a new way of being and not being in the system — but how can we do both? Can we?

We must, because we cannot now meet the world with these kinds of systèmes de pensée or pensées de système. It is impossible. Moreover, the world we live in will not allow it.

Consider, in the seventeenth century, the tremblement de terre de Lisbon, the great earthquake of Lisbon, nobody knew about it. Nobody knew until Voltaire wrote poetry about it. But if there is a flood in China today, we know about it immediately. We are immediately in the flood. If there is a typhoon, we know it immediately. We see the typhoon coming, coming, and coming, and coming to Haiti, to Jamaica, to Florida, to Louisiana, and we are in it.

So the difference with the old times is that today we cannot escape the inextricability of the world. And in order to be in contact with the world and to try to help the world, we cannot be tied to a system of thinking. We need trembling thinking — because the world trembles, and our sensibility, our affect trembles.

You once used a phrase that I now use myself, tourbillons de rencontre, “whirlwinds of encounter” —

Before that — I must say trembling thinking is not a way to forget or to dismiss your identity. Because people always tell me “Yes, yes, ‘trembling thinking’ and all that, but I am what I am, and if I am what I am, I cannot forget or dismiss what I am.” But you do not have one identity, forever. You can change without diluting yourself. This is important, because otherwise you might see trembling thinking as a kind of renunciation.

The oppressed, who are denied their identity, understand what I am saying, because they have a conception of relational identity; a capacity to move beyond identity. The oppressors, however, don’t, because they are committed to a fixed identity — identity as a single root. The thinking of tremblement is this: even when I am fighting for my identity, I consider my identity not as the only possible identity in the world.

And to your question of tourbillons, of whirlwinds, let me say that there are people in stasis, that means they don’t change, they’re like Switzerland — neutral — but it’s good, it’s okay. And there are people who change — every time they move. And trembling thinking reconciles the Switzerlands and the nomads. It conciliates people who don’t change and people who change every time, through such whirlwinds of encounter.

And you’ve said we can actively bring about whirlwinds of encounter. In 2007, you staged readings at the Musée du Quai Branly and at La Maison des Métallos in Paris, where people came to read texts on slavery for an audience. Each text was read by one person — they’re all on stage and, in turn, they step forward to read the texts. How did the event unfurl?

Rousseau, yes. Texts from the Code Noir, the code that fixed the rules of slavery, a monument to barbarism.

So, monuments to barbarism and protests against barbarism.

Texts that made and unmade slavery.

Like a sort of shock of differences…

Exactly. And to keep us from forgetting the monstrous and proliferating nature of slavery.

No Frenchman in France today appreciates the role France played in the Atlantic slave trade, the English hardly any more than the French. First England, and then France, accumulated the capital that made industrialization possible through the African slave trade and slave labor. This is what allowed the development of England and France in Europe.

Spain, which did not participate in the slave trade and bought slaves from France and England, was two centuries behind economically and has only recently caught up.

Therefore, the study and understanding of how slavery shaped our current world is fundamental, not only for us, the descendants of slaves, but for the descendants of slaveholders. And we have to set the historical record straight, so that, on the one hand, there is no longer ignorance, contempt, indifference, or condescension and, on the other hand, there is no longer rancor, hatred, impotence.

Since then, you’ve also made other manifestos, like the one with Patrick Chamoiseau, When the Walls Fall. It’s magnificent.

And also The Unassailable Beauty of the World, an address to Obama when he was elected President of the United States. Those texts are meditations on the state of Black people in the Americas in general, and in the United States in particular, but also on the significance of Obama’s election as someone born of colonization — not just someone of Black race, someone of colonization. We say to him: you have emerged from the abyss, the abyss of the slave trader’s boat.

We try to highlight its symbolic significance and impact on the world, the imagination of the world.

And that makes me think, too, of your work with Frantz Fanon, who was a classmate of yours. Together, you played a role in the movement for independence in Martinique, a movement for the decolonization of the French West Indies. That was a political collaboration, not a literary one. You founded the Front Antillo-Guyanais to fight for this. But with the start of the Algerian War in 1961, you were perceived as such a political threat to France that you were arrested and held in administrative detention — and were not allowed to return to the Caribbean for fear you might start a revolt. This was contrary to the position of Aimé Césaire, who taught both you and Fanon, who was accused of working too closely with the French government — and people thought it was terrible of him to let Martinique take the status of département of France rather than seek full independence, no?

Yes, and this was certainly the case. Césaire believed it would be better to join France, but in doing so he overlooked the fact that French national identity, even when it mixes with other cultures, aims to obtain a unity. It seeks this unity rather than confirming diversity. And the movement to obtain unity requires a mixing that could be accepted by all people, without leading to a war or a conflict. It is a means of stifling independence.

So in 1946, Césaire led the Martinicans, and Guadeloupeans, and Guyanese to obtain the status of French départments — states with representation. But I remind you that Ho Chi Minh asked in the same year for the status of a department — and France gave it to Césaire but they didn’t give it to Ho Chi Minh. The two of them often spoke about it. Why did France do this? Because Martinique is very little and they did not fear Martinique, but they feared Indochina. So you see, this colonial process aims always to produce a controlled unity.

What form does the anti-colonial movement take today?

Well, we cannot restart the anti-colonial movement as it was in the time of Patrice Lumumba. By the way, Guadeloupe in the 80s had a big independence party, but little countries like this don’t have arrière-pays, hinterlands, where revolutionaries can wait and gather. So this movement failed. We have to think of another way of fighting, of struggling now.

There are so few hinterlands left, and they are so cut off — as you’ve said about the countryside and the city —

The movement of the twentieth century was to mega-cities, which killed and enslaved the countryside. But now the big cities will suffocate and we’ll move in the other direction, so perhaps the hinterlands will flourish again.

We recently had a conversation with Rem Koolhaas about precisely this, and I remember he asked you about this belief in the future of the countryside.

Yes, and I said that I suspect there will be rural revivalism — remember that in Medieval Europe, the city was exploited by the countryside, but it was also the defense of the countryside. When the countryside was invaded, everyone took refuge in the city. Well, in the future, everyone will take refuge in the countryside.

Accordingly, a new style of architecture will emerge concerned with the interior rather than the exterior. An architecture which will permit you opacity, let you live without being seen.

Interestingly, Koolhaas challenged you on the fact that, across the Western world, the culture of the countryside is rightwing.

Well, this, historically, is not the case with Latin America. Its countryside is the culture of Emiliano Zapata, Pancho Villa, the revolutionaries. When revolutions take place in the Americas, they go to the countryside. Castro did not go straight to Havana, he went to the Sierra Maestra, to the mountains. I think the countryside is the place where, certainly there have been regressions and ideologies, but the countryside is also the place where there are revolutions. It’s like the acoma.

The acoma?

The acoma is a tree in the forests of the West Indies, one of the largest and most beautiful trees in the country. Long after it’s been cut, the heart of the tree is still just as moist and full of sap, as though it’s been chopped down only moments before.

So the heart of these movements remain alive, waiting, but they need another form, a new approach?

Yes. And to do this, we need archipelagic thinking, which is one that opens, one that conforms diversity — one that is not made to obtain unity, but rather a new kind of Relation. One that trembles — physically, geologically, mentally, spiritually — because it seeks the point, that utopian point, at which all the cultures of the world, all the imaginations of the world can meet and understand each other without being dispersed or lost.

And Acoma was the name of your journal too — which is what your school on Martinique grew out of. It makes me think of a very important discussion right now, which is the creation of a new Black Mountain College. Was your school a means of resistance? I certainly find this interesting because you yourself resisted going to school.

Yes! But going to school and “going to school” are very different. What I don’t like is the idea of having literary disciples.

Sometimes the artists who have founded a school, an institution, have done so with the aim of “making a school,” with the intention of transmitting a doctrine or a system. But that’s exactly what you didn’t do.

Creating the school in Martinique was mainly motivated by the fact that it was urgent. There were lost generations in terms of education. There was a massive phenomenon of young people rejecting the French education system, so it was imperative to find an alternative. The reasons that prompted me to create this school were therefore independent of literature. For example, I never sought to impose my own conceptions of art or literature within this establishment. If, moreover, I do not agree with the idea of a “literary school” it is because I consider the adventure of creation to be an enterprise, admittedly common, but fundamentally lonely. On the contrary, the school was a collective work. In that sense, it was a means of resistance, yes. Resisting what a school typically is, always pushing us towards trembling thinking, and searching for a conversation with many voices — because the best answers come through conversation, whether between people, like us, or between art, literature, et cetera.

Credits

- Interview: Eliza Levinson