SUPREME NEW YORK

|ALEX HAWGOOD

“The fashion industry doesn’t understand SUPREME,” says the stylist Andrew Richardson, who has helped facilitate several projects with the label including a calendar with Larry Clark. “And that doesn’t bother James one bit. They want James out and about, paying for dinners and hosting parties. But he’s not. Fashion people want something that is uncomplicated and easy to digest – those are the opposite things James embraces. But really at the end of the day, James doesn’t care. Why should he?”

When the controversial young rapper Tyler, the Creator won the award for Best New Artist at the 2011 MTV Video Music Awards in August 2011, he offered an enthusiastic, yet expletive-laden acceptance speech. “Yo, I’m excited as fuck right now, yo,” he said. “I wanted this shit since I was nine. I’m about to cry.” But with MTV’s censors on high alert, the speech was broadcast more like this: “Yo, I’m excited as — —- —- —, yo. I wanted —- —- —- – — —-. — —– — —.” With the audio missing for about a minute straight to avoid any profanities and Federal Communications Commission (FCC) fines, viewers were left with no choice but to absorb Tyler’s image in mute. Clad in skinny dark jeans, an oversize tie-dye T-shirt with an image of a cat’s face on it, and a Supreme baseball hat with a leopard print brim, Tyler, who is 20 years old, was the only artist at the award show who could be said to actually embody how young people dress today. No outfit made from meat, no fancy three-piece suit with a cocked fedora, no oversize bling: Tyler looked exactly how certain young men at this very moment choose to wear their clothes on the streets all over the globe.

It’s no coincidence that the only logo the image-conscious Tyler wished to communicate was the one on his Supreme hat. After all, Tyler’s hodgepodge street aesthetic – a big chunk of skateboard culture and urban hip-hop with a dose of American sportswear prep and a winking, intelligent take on hipster irony – is the one Supreme has been cultivating for the past 17 years since opening its first shop on Lafayette Street in 1994. The flashy sartorial sensibilities of, say, Russell Brand or Kanye West have mutated into their own category of sub-entertainment and, more often than not, their personal styles do not reflect the current vogue. So how then did the Supreme aesthetic finally become one of the most honest representations of how men choose to wear their clothes in the global mainstream today?

It’s easy to answer that question if one concedes that Supreme currently makes some of the best clothes for men in America right now. And for a brand routinely overlooked by fashion publications and menswear experts as “skate clothes” or, perhaps even worse, just a fad in a niche subculture, this may come as something of a surprise. But can you blame the press for sleeping on it? For almost two decades, Supreme has existed in a cult-like bubble. Many of their short-run products have a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it shelf-life; you’ll pretty much never, ever receive an invite to some Supreme-sponsored open-bar fête (because they almost never happen); and unless you’ve been systematically tracking its product developments on the array of feverish blogs devoted to the brand, or know a mole on the inside who can text you when a new shipment has been delivered, you’ll miss out entirely.

“In the early days, it was like, come in, but don’t touch. You can look with your eyes, but not with your hands. It was a crazy way to sell garments but the customer learned the deal: don’t fuck with us and we won’t fuck with you.”

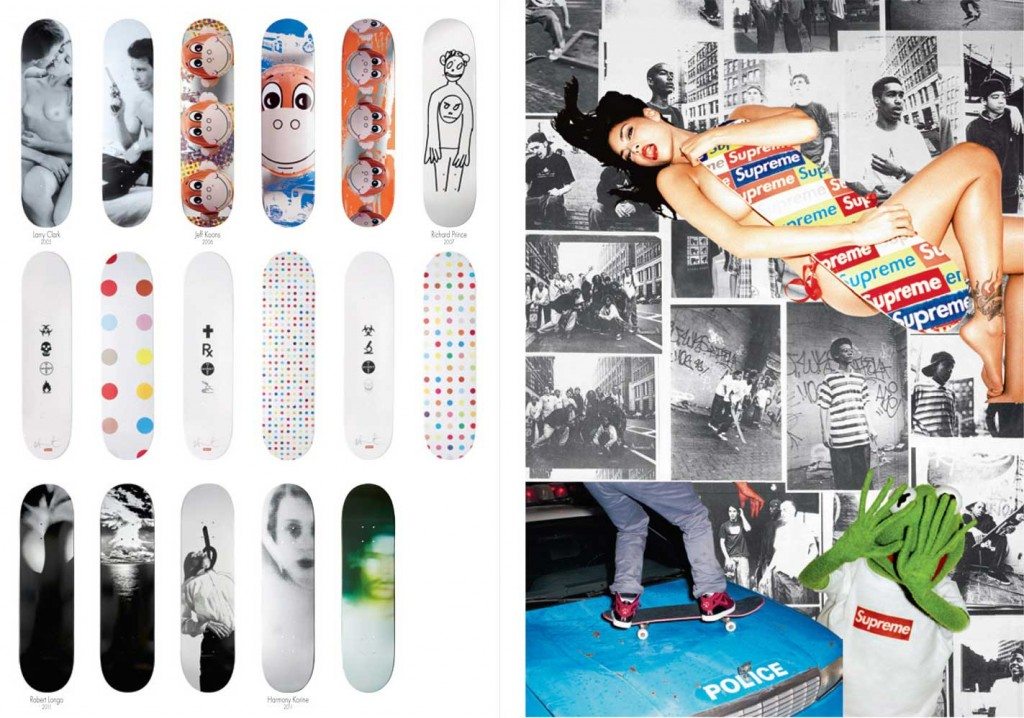

Starting with its swagger-filled moniker, the label certainly has built a colossal and often intimidating public aura. “The most important thing I think is the name – Supreme,” says the art photographer ARI MARCOPOULOS, a frequent collaborator whose images have helped define the brand’s visuals, including having his work silkscreened on an assortment of sneakers for the label’s partnership with Vans. “Really, you cannot do much better than that.” Being sovereign – the supreme ruler of culture – is the brand’s unofficial mission statement; everything is appropriated, recontextualized and refitted in Supreme’s hands to be made better. (Not the least of which is the fire-truck red box logo ripped from the oeuvre of Barbara Kruger.) Chinos are constructed with military-grade reinforcement, hats are made with a sturdy square brim, and T-shirts are twice as thick. They’ve carefully chosen to cross-pollinate their homegrown image with unhip but timelessly macho brands like Hanes and The North Face, worked with blue-chip artists such as Jeff Koons and Christopher Wool for their art-deck series, and built ad campaigns around a motley crew of celebrities that have no direct connection to skateboarding, including Kermit the Frog, Mike Tyson and the pop star Lady Gaga. In fact, the brand’s biggest appropriation of all is the very idea of what a skate shop is – or isn’t. “I don’t see Supreme as a skate shop at all,” says STEVE RODRIQUEZ, the owner of 5boro Skateboards and one of the founding members of the New York City Skateboarding Association. “It started a whole new genre of store. To some people, it became like a religion.”

Like most religions, JAMES JEBBIA, Supreme’s founder, is fiercely protective of his shop’s doctrine, its history, and of who is allowed to retell its myths. To him, most articles in the press about his brand get it all wrong. “All the magazines, if they’re being nice, just think we’re some cool little skate shop doing kick flips downtown,” Jebbia says. “They always write the same thing over and over.” Because of this belief system, Jebbia and his team are notoriously press shy. Although Jebbia is soft-spoken and quite generous (by the end our conversation he offered me a checkered North Face for Supreme hat that was no longer on the shelf at the store but still in stock), he is cautious and skeptical about the media and those who write for it. “If you don’t understand us, then what’s the point?” he huffs, referring chiefly to the confusion on how to treat the brand (is it an X-games label like Quiksilver and Billabong, or a legitimate small fashion label more similar to agnès B or A.P.C.) and, more troublingly, the frequent pigeonholing of skateboard culture within the fashion industry as just a passing fad, no different from big shoulders or neon colors.

There are so few examples of stories about Supreme that Jebbia finds successful, he treats the chosen pieces like scripture that he is eager to share. The holy writ includes an interview with Glenn O’Brien from Interview magazine from 2009, a 1995 article from Vogue comparing the persnickety shopping habits of the uppity uptown women who peruse the racks at Chanel’s boutique on East 57th Street and the baggy-pants, bed-head boys who wait in line for hours at a time to shop at Supreme in SoHo; and of course, the 300-page retrospective of the brand released by Rizzoli last year (of which Mr. O’Brien wrote the introduction, and in which the Vogue article was reproduced in full.) The message is clear: Supreme is sacred, and it’s sacrilegious to get the story wrong.

“The fashion industry doesn’t understand Supreme,” says the stylist Andrew Richardson, who has helped facilitate several projects with the label, including a calendar with Larry Clark. “And that doesn’t bother James one bit. They want James out and about, paying for dinners and hosting parties. But he’s not. Fashion people want something that is uncomplicated and easy to digest – those are the opposite things James embraces. But really, at the end of the day, James doesn’t care. Why should he?”

Hearing Jebbia talk about the press, you don’t get the impression that he is paranoid about being criticized or that he is tyrannical over what is written about his beloved brand. Most articles simply do not live up to the gold standard he has set for his label and himself, or the one expected from his fastidious customer-base. The impression is that most writers and publications are not worthy. “We always try to shoot for the very best and go for it,” he says. “Some people call that snobbery, I guess. But it’s not.”

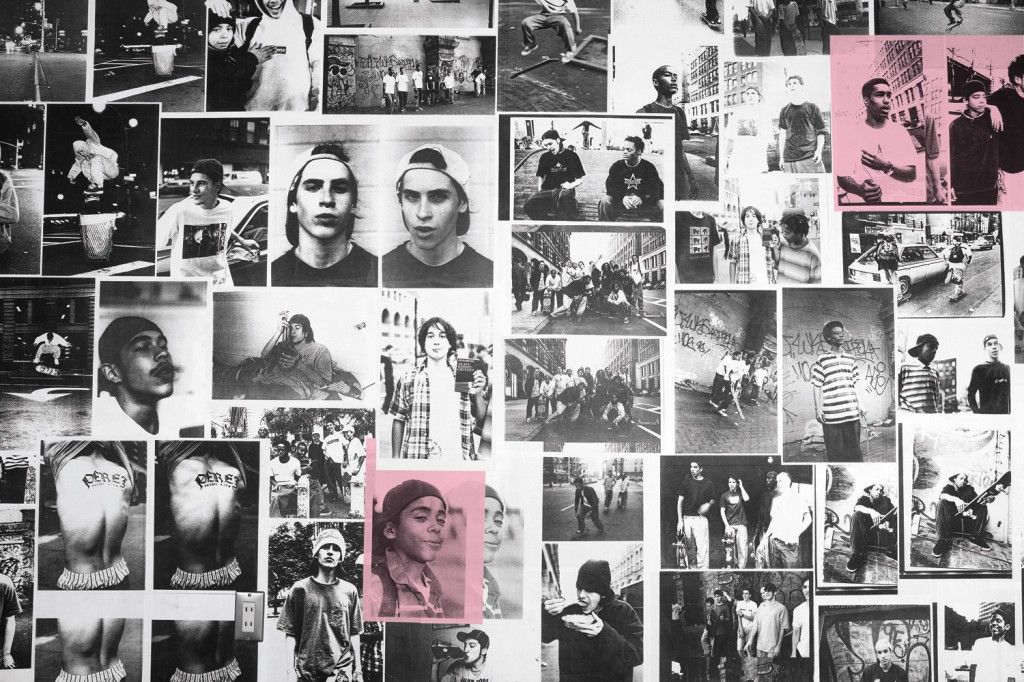

Indeed, selectivity and exclusivity are an integral part of the brand’s DNA. When the shop opened in 1994, it immediately became an epicenter for what AARON “A-RON” BONDAROFF, the label’s front man, has called “train-hopping, taxicab-jumping, runaway kids.” And dudes from all over the city followed in reverence, often lining up for hours to be the first to score the latest products to come in, like candy-colored baseball caps or spacious bomber jackets with the Supreme logo shown discreetly on an outside tag. And even if you made it inside, the really real cool kids knew to ask for the hidden, in-the-know merchandise in the back storage room. Remembers Bondaroff:

“The social club wasn’t so inviting, though, and had a lot of attitude. We made the rules and ran a business that was very successful. People were addicted to the clothes like a drug. We didn’t want to work so hard so we developed a sales style that worked in our favor. In the early days, it was like, come in, but don’t touch. You can look with your eyes, but not with your hands. It was a crazy way to sell garments but the customer learned the deal: don’t fuck with us and we won’t fuck with you.”

The store was so cool, it was, well, scary. “I remember being so nervous walking past it, I would walk across the street,” says JEN BRILL, a freelance creative director and “friend” of the brand since it’s inception, “even though a lot of the guys that worked in there were my friends. It was effective, though, and set an impeccable aura around the shop.”

In an interview with the graffiti artist KAWS from the Supreme retrospective, Jebbia maintains that, even in his own tank, he too felt like a fish out of water: “There were 50 or 60 skaters who’d just hang out there. And right at that time, too, Larry Clark was filming Kids. For me, again, it wasn’t part of my world, but I knew it felt very rebellious. It felt right and I liked it.” Hiding out in the back room and letting the kids rule the roost allowed Jebbia to observe the natural habits and tendencies of his clientele, not unlike the objectivity achieved from a behavioral psychologist studiously taking notes behind a two-way mirror. He didn’t have to be a skateboarder at all, he just had to know what this new generation of skate kids wanted and what they weren’t getting anywhere else. Most importantly, Jebbia developed the cunning to anticipate what they needed next. If you’re too far in it, you can’t see outside. The distance from the lifestyle, conversely, gave Jebbia a sublime ability to understand how best to represent the lifestyle. “I think James is always thinking with a 25-year-old skateboarder somewhere in his mind with everything he does,” says Richardson.

The mythology behind Supreme is so potent, it’s easy to imagine Jebbia as a king pin of downtown New York. But as he will be the first to tell you, that couldn’t be farther from the truth. In fact, Jebbia has gone to dramatic lengths to make himself not a poster child for downtown New York. With this soft-spoken English accent and uniform of T-shirt and blue jeans, he happily relinquishes the pressures of being the brand’s face to Bondaroff. “What I do is rock the clothing and keep the spirit alive,” Bondaroff says. “I live the brand philosophy, if that makes sense.”

In actuality, Supreme’s core creative and business philosophies are the sum of Jebbia’s patchwork retail past; not, as one might assume, a storied legacy in skateboarding. His resume reads like a series of interconnected Google-map pins on a late-80s and early-90s SoHo New York. A British-transplant who arrived in New York around 1984, Jebbia got a job working at the now-defunct Parachute clothing store in SoHo. “I didn’t know what I was doing, but I knew I enjoyed clothes,” he says. He quit five years later to open, along with his girlfriend at the time, a small flea market on Wooster Street inspired by the myriad of stuff he coveted from The Face and i-D magazines. The project evolved into his first proper store, Union, an experimental shop on Spring Street that carried “mostly English brands” and one very important streetwear juggernaut at the time by the name of Stüssy. This allowed Jebbia to work with Shawn Stüssy, who asked him to partner with him to open one of his eponymous boutiques on Prince Street in 1991. When Stüssy left the business, Jebbia opened up Supreme in 1994 in a small storefront on Lafayette, a then-desolate street that was a perfect place for his clientele to skate first, shop second – an order that would very quickly be reversed. “I opened Supreme because there were no other decent skate shops around at the time,” Jebbia says. “I thought, cool, I might as well be the one to do it.”

“After Brooklyn Banks,” the unofficial name for the area under the Manhattan side of the Brooklyn Bridge, whose smooth terrain made it a popular skateboard destination, “kids wanted to go to Supreme right away,” says Rodriquez. “It totally represented the non-skateboard aspect of skateboarding in a very powerful, unavoidable way.”

The store was able to become the holy grail of high youth street culture by curating a mix of the city’s iconography – fashion, music, celebrity and politics – within its walls and then instantly sledge-hammering the city’s high-low playing field. Limited-edition Damien Hirst skateboards are around the same price as decks featuring lyrics from Public Enemy; custom Spalding basketballs might be sold under the artist Nate Lowman’s gritty canvases hanging on the wall. The brand’s iconic T-shirts, like everything in the store, have become collector’s items that are collages of controversial provocations and heady imagery. Designs have included an oversized New York Times logo, a portrait of Kate Moss, lyrics from the reggae musician Lee “Scratch” Perry, Mickey Mouse’s hands praying with rosary beads, Budweiser labels, and alarmist political slogans such as “Illegal business controls America.” Juxtapositions abound: images of naked girls playing with a hose pop up in a calendar from 2006 but more cerebral women like Chloë Sevigny and Ms. Brill act as brand ambassadors in Japanese style magazines; one of the brand’s most iconic image is of the rapper Raekwon, an Elmo doll, and an Uzi show by the photographer Kenneth Capello. And really, who would have thought Lou Reed would ever become the label’s face, as he did in 2009? “Supreme embraces the outsider and always does things off-value from their brand,” says Richardson. “But they’re consistent and have always embraced the outsider and the individual. At the end of the day, Supreme is about the legacy of punk through skateboarding and you can really genuinely feel this in everything they do.”

The brand’s insidery-outsidery brilliance often made them precursors to trends that would later pop-up on the catwalk, such as their collaboration with Richard Prince as part of their art deck series well before Prince joined forces with Marc Jacobs to make handbags. “I like to point that out,” Jebbia says with a smile. “Not to be that guy, but just, you know, to point it out.”

The Supreme brand and its products soon became viable forms of creative expression, which in turn became catnip for a particular breed of male consumer hungry for that indefinable but high-quality cool, resounding most immediately with Japan. “We never purposefully went after a Japanese customer,” Jebbia says. “It wasn’t like that. It’s always been about that really picky New York customer, but I think that translates all over the world.” Nonetheless, the Japanese consumers hyper-related to Jebbia’s choosy modus operandi and were quick to embrace the Supreme product as something culturally valuable and worth a premium price. “Japanese kids respect underground movements and have a good eye for it,” says Bondaroff.

Supreme now has five stores scattered across Japan and just opened their first store in London, featuring installations from the artists Mark Gonzales and Ari Marcopolous, this past September. “We’ve always really been inspired by London youth,” says Jebbia. Evidence of his grimy South London influence can be seen in many of the Supreme staples, such as military jackets, beanies, and oversized Oxford shirts with a neat fit. But there is also a business component to setting up shop across the pond. “For us, London is the real gateway to Europe,” Jebbia says. Now kids won’t have to fly from all over Europe to come to New York to get a piece of Supreme. “We hope it makes things easier for them, honestly. It can save them a plane ticket, you know what I mean? But, we’re keeping the shop with the same spirit, it will feel like New York.”

In the past, owning a piece of clothing with the red Supreme logo on it was like a more authentic “I Love NY” T-shirt, a tourist token that instantly made you feel a part of a certain downtown New York ethos. Jebbia is mindful of this, but he doesn’t seem worried about diluting the potency of his brand by going global: “We’re not going to open up stores everywhere, that’s just not us. I can’t even think of somewhere else I would like to open, really.”

Supreme has been able to grow, but Jebbia has always been able to keep his hand right on the faucet, letting out just enough but not too much. “Supreme represents fresh ideas done right,” says KENNETH CAPPELLO. “They’re always one step ahead and always limited, so people want it.” Mr. Jebbia, however, is playfully cautious about the idea that his small production runs are part of an exploitative plan to skew supply and demand to fever-pitch levels. “The main reason behind the short runs is that we don’t want to get stuck with stuff that nobody wants,” he says. But admitting to a kind of customer trickery isn’t exactly the coolest thing to say, so you let him be. “Let me put it this way,” he adds tellingly. “We work really, really hard to make everything seem effortless.”

As the shop is on the horizon of its second decade in business, all that hard work has become the focal point for a type of New York aesthetic that is just now entering the canon of great American dressing. When it first opened, the shop was a reflection of the times: the raw energy of Larry Clark’s film Kids; the haphazard elegance of grunge; the polished grit of the East Coast hip-hop movement of the time. In Jebbia’s conversation with Glenn O’Brien from the piece in Interview he asked me to read, Jebbia spoke about the lasting influence of that era in his brand’s sensibility:

“There’s always, I think, a sense of the early-90s to it. That era is definitely a big influence running though everything we do – that was a really special time. And since we started back then, I think it’s fine for us to always look to that era and get a lot of influence from it. It’s not nostalgic – it’s more like it’s a part of us.”

“Illegal business controls America.”

It’s been almost 20 years since the birth of this aesthetic, and now, with most menswear designers aimlessly searching in tea-soaked history books for authenticity, it has never felt more right. If Polo reflects a sense of country club prep and A.P.C. a type of louche French rock ’n’ roll (two brands Jebbia says he greatly admires), Supreme has then its own unique form of authentic, time-encapsulated style in early-90s skate culture. But now, the baggy pants are a little bit more fitted; the Oxford shirts come in a more sophisticated palette of colors; the imagery is more mature. And while other designers such as Rag & Bone, Tommy Hilfiger or J.Crew hark back to a phantom sense of American heritage, Supreme actually embodies a new garde of American classicism without dwelling in dusty clichés. The little skate-shop-that-could has unexpectedly grown to foster one the strongest statements in men’s sportswear – the hallmark of American fashion – in quite some time.

“People think that because we are widely-known as a skate shop, our clientele must be idiots. But they want new things on a high level. All they care about is quality,” says Jebbia. He is right, after all. Today, the globalized customer demands a certain tasteful efficiency, not the trappings of exclusivity. To date, Supreme has chosen to refine their signature products, not to forge themselves out in wild, unpredictable directions with their design process, but instead to forge themselves out in new directions in the world at large. “The product keeps getting better and better,” Bondaroff told me in a phone interview. “It’s so solid now, it crosses over to so many different types of people depending on how they want to wear it.” Solid, in this case, means well-proportioned sportswear without a lot of frill; done with a discerning eye for what is wearable – take a long-sleeved double-ply flannel in yellow, brown, or green, for example. Therein lies Supreme’s striking paradox. Underneath its tough exterior, the brand has always traded on something of cool’s polar opposite: pragmatism and utility – with a keen sense of graphics and sharp design, no doubt.

The crucial thing to know about Supreme clothes is that they reflect everyday style for men. But more importantly, they assuage the fears many men who have come of age alongside the store have about wanting to look grown up – or, dare I say, appropriate – while still being true to their core aesthetic values that Jebbia speaks of. Almost two decades later, the Supreme project has become an updated take on that oh-so American sense of function and pragmatism. It’s a design philosophy that has mostly been missing in men’s fashion in recent years. “Quality” is a word Jebbia stresses over and over again in conversations about his brand. You get a sense that he is growing impatient with just being known for on-the-nose artist collaborations or an effervescent downtown credibility. His brand’s true worth, and what his customers fetishize above anything else, is its casual matter-of-factness. Nothing looks sharper, but there is nothing snobby about that. There is something universal about it, really. If fashion and award shows have any teachable moments, it’s that cool doesn’t last on the fickle world stage. Quality does.

“It’s not really just a cool skateboard thing anymore. People resist that idea still. It frustrates me,” Jebbia says before taking a pause. “Oh well.”

Credits

- Text: ALEX HAWGOOD