JACQUES DE BASCHER: An Exhibition

|IRINA BACONSKY

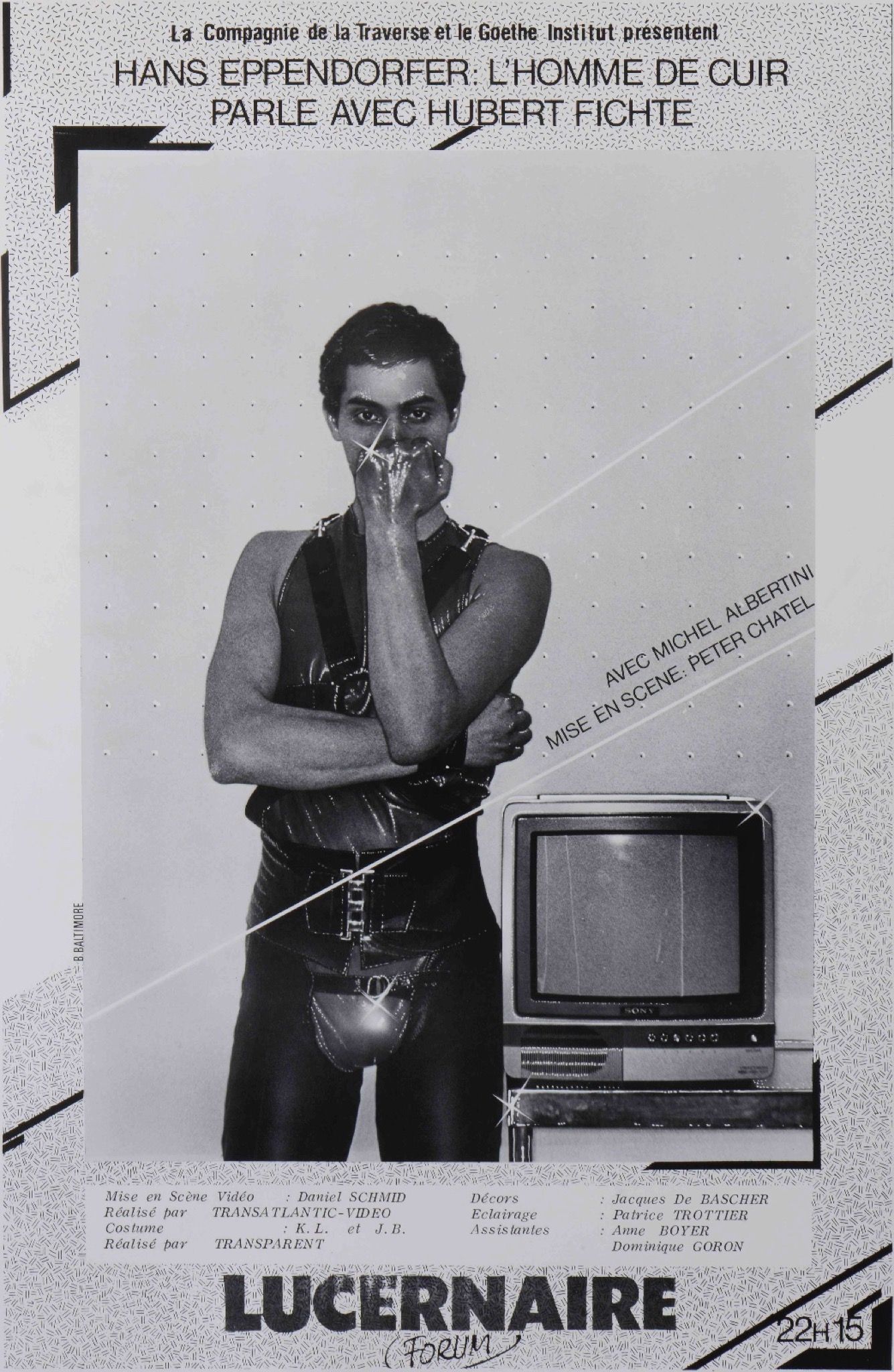

Europe has a long history of well-bred dilettantes, socialites, and dandies that have made fringe careers of skating the razor-sharp edge between pleasure and downfall, viewing death as life’s grandiose work-in-progress rather than its end. One such notorious aesthete was Jacques de Bascher (1951 – 1989): ambiguous companion to Karl Lagerfeld for more than 18 years, extravagant life of the 1970s champagne-soaked Parisian party scene, debauched erudite with a penchant for beauty and self-destruction, and “artist with no work except that of his own life.” Last week, roughly a year after Lagerfeld’s death, an exhibition devoted to his (apparently platonic) protege opened at Paris’ Treize gallery, featuring archival images and video, ephemera, personal objects, and totems. “Jacques de Bascher, An Exhibition” curators Charles Teyssou, Kevin Bildermann, and Pierre-Alexandre Mateos discuss the relevance and challenges of documenting its titular subject’s fleeting intensity and semi-religious devotion to cultured decadence.

Irina Baconsky: What makes Jacques de Bascher a cultural figure worth celebrating, especially today?

When Karl Lagerfeld died almost one year ago, he took with him an idea of fashion, luxury, and ostentation that was not entirely linked to rentability and productivity. Paradoxically, Lagerfeld championed fashion’s commercial transformation while at the same time loving Jacques de Bascher, who dedicated his life to consuming [what Georges Bataille called] the “accursed share” of society. In that sense, de Bascher adhered to Bataille’s theory of luxury, according to which the excessive and non-recuperable portion of human economy subverts the balance of the current system by over-investing in luxury, ostentatiousness, non-reproductive sex, architectural follies, and sumptuous balls. Celebrating de Bascher could seem anachronistic, as he embodied a dandy lifestyle utterly disconnected from any political, social or economic realities. A figure like him can appear totally out of touch. He invented himself as a fictional character à tiroirs, to borrow a French expression we could translate as a “matryoshka” type of persona. Yet this way of living was perhaps his most radical act. He turned his life into a violent mix that was somewhere between a work of decadent English literature and an avant-garde 1970s New York sex club. Once, when on a Concorde flight to New York, high on Mandrax, he saw himself as Ludwig II of Bavaria riding his bark in his artificial lake inside the Venus Grotto of his Linderhof Palace.

Instead of producing work or leaving behind a material legacy, many figures have attempted to turn their own lives into their magnum opus, to be a breathing artwork. Was de Bascher’s decadence his art? Did he view it as such?

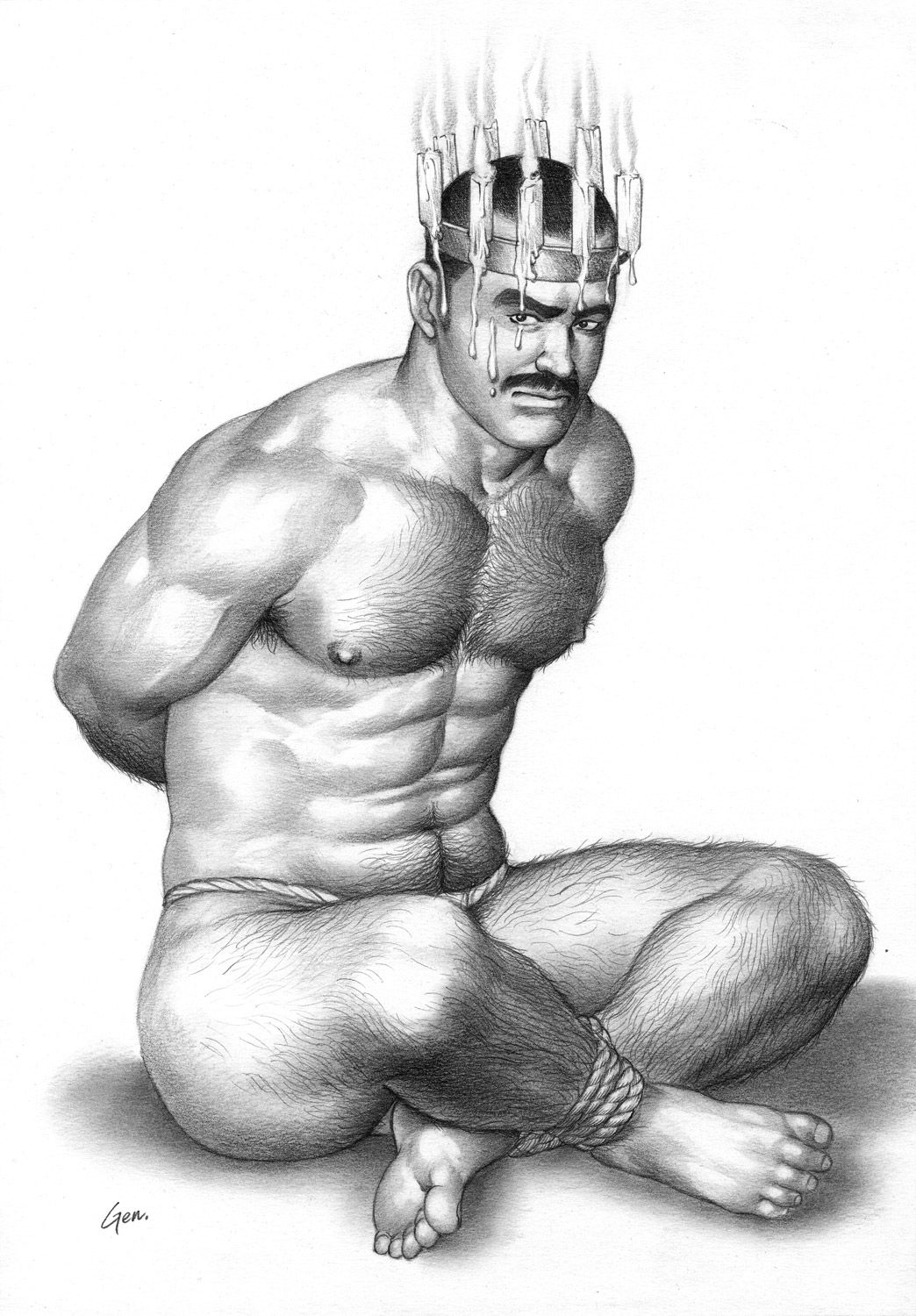

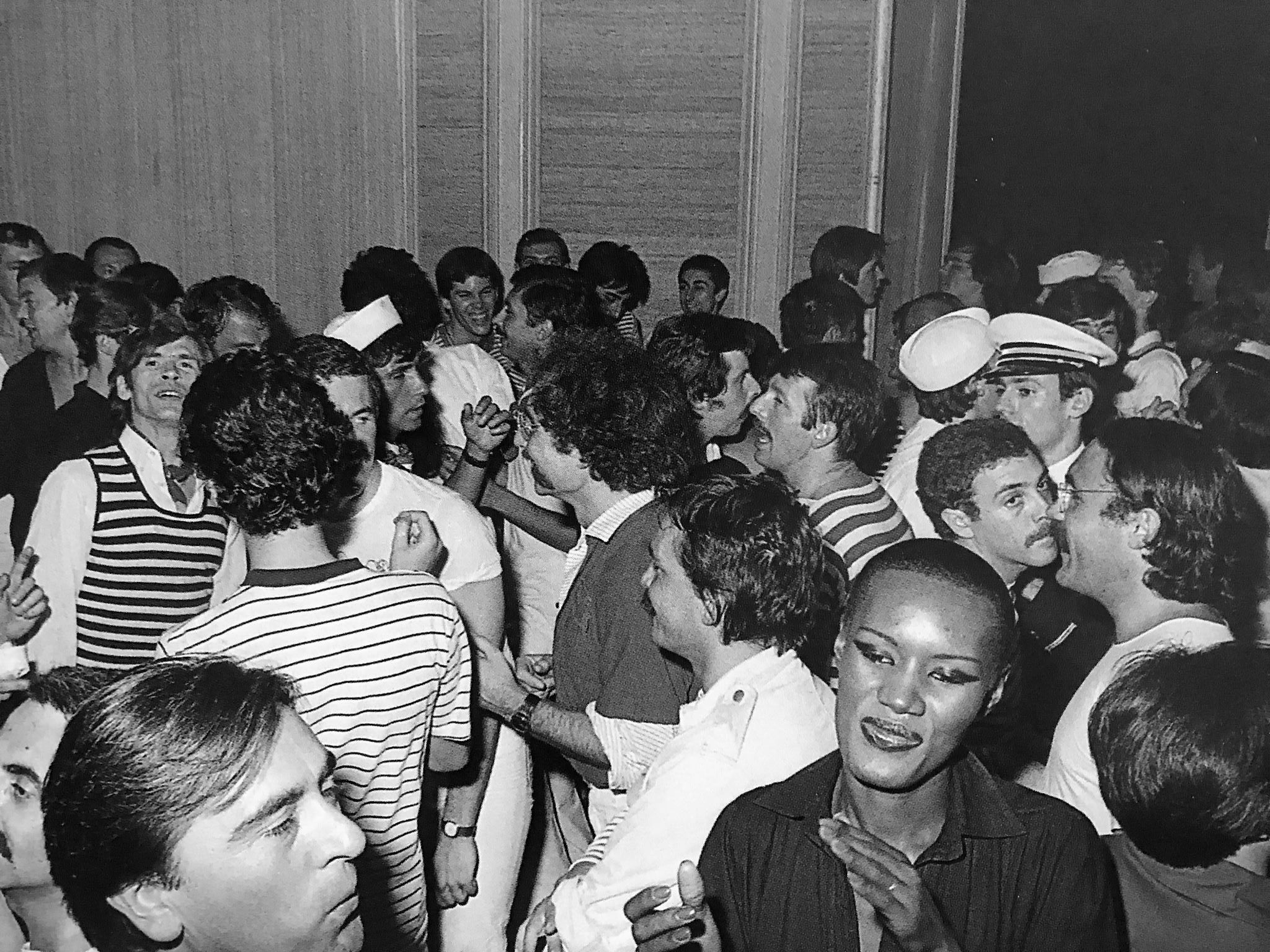

Yes, and this is precisely why an exhibition on him is a particularly challenging task: decadence cannot be recorded or reenacted. On a curatorial level, we had to invent proof of events or facts that have long disappeared – we had to produce the napkin he used to dry his forehead after he lost his virginity to his high school teacher. He was interested in extreme characters such as Gilles de Rais, a 15th century lord known for having tortured and murdered 140 children, and Jacques d’Adelswärd-Fersen, an early 20th century French novelist and poet who was sued for organizing what the media called “Black Masses,” for which he summoned upper class young boys to his Parisian home in order to stage sexual tableaux vivants. D’Adelswärd-Fersen was later exiled in Capri, where he built the decadently neoclassical Villa Lysis and he wrote Lord Lyllian, a novel partly inspired by his trial as well as that of Oscar Wilde. This passion for extreme forms of corporeal intensity manifested in the dinners and balls de Bascher himself organized, often evoking the spirit of these authors. He once organized a white dinner mirroring the black dinner in Huysmans’ À rebours, in which the décor, the guests’ attire, and every course was white. The finishing touch was a silver plate gorged with cocaine. His most well-known endeavor of this kind was probably the Black Moratorium, a BDSM party held in 1977, which gathered Paris’ socialites and fashionable coteries around fisting performances, fencing competitions, and group sex.

De Bascher started out as an Air France flight attendant before he became a fashion muse, personifying excess and dandyism for Karl Largerfeld and Yves Saint Laurent. Despite the luxury, for him the line between life-affirming opulence and self-destruction seemed to be quite narrow. What did death mean to de Bascher? Was it simply an aesthetic fetish?

In an interview with André Léon Talley for Interview magazine, de Bascher said: “Decadence comes from the Latin cadere, which means to fall. To be decadent is a way to fall in beauty. It’s a very slow movement, very beautiful. It can be a form of suicide in beauty.” A voracious appetite for beauty, when taken to an extreme, can only result in death. He loved beauty and intensity in equal measure, which explains the fact that cocaine was his Achilles’ heel. Among his heroes was also the aviator Alberto Santos-Dumont, who famously owned a bespoke Cartier box with a telescopic metal straw, which he used to snort cocaine while flying. An electrifying figure such as de Bascher could not live long. This is probably why Karl Lagerfeld wrote a message accompanying hundreds of bouquets of white lilies he bought for his funeral that read “SIC SUIT IN FATIS,” which means “it was his destiny.” We bought the exact same flower, from the exact same flower shop, for the exhibition as well.

The figure of the dandy was prominent in the 19th and 20th centuries. Why do you think it died, and what has replaced it today ?

Dandyism is the fatal attraction toward beauty in every aspect of human existence. It is an ideal above all else, and it can seem frivolous, if not detrimental in a period that can barely produce great narratives. I don’t think there are any successors to the figure of the dandy, and I doubt that such a successor could exist in today’s world.

Credits

- Text: IRINA BACONSKY

- :