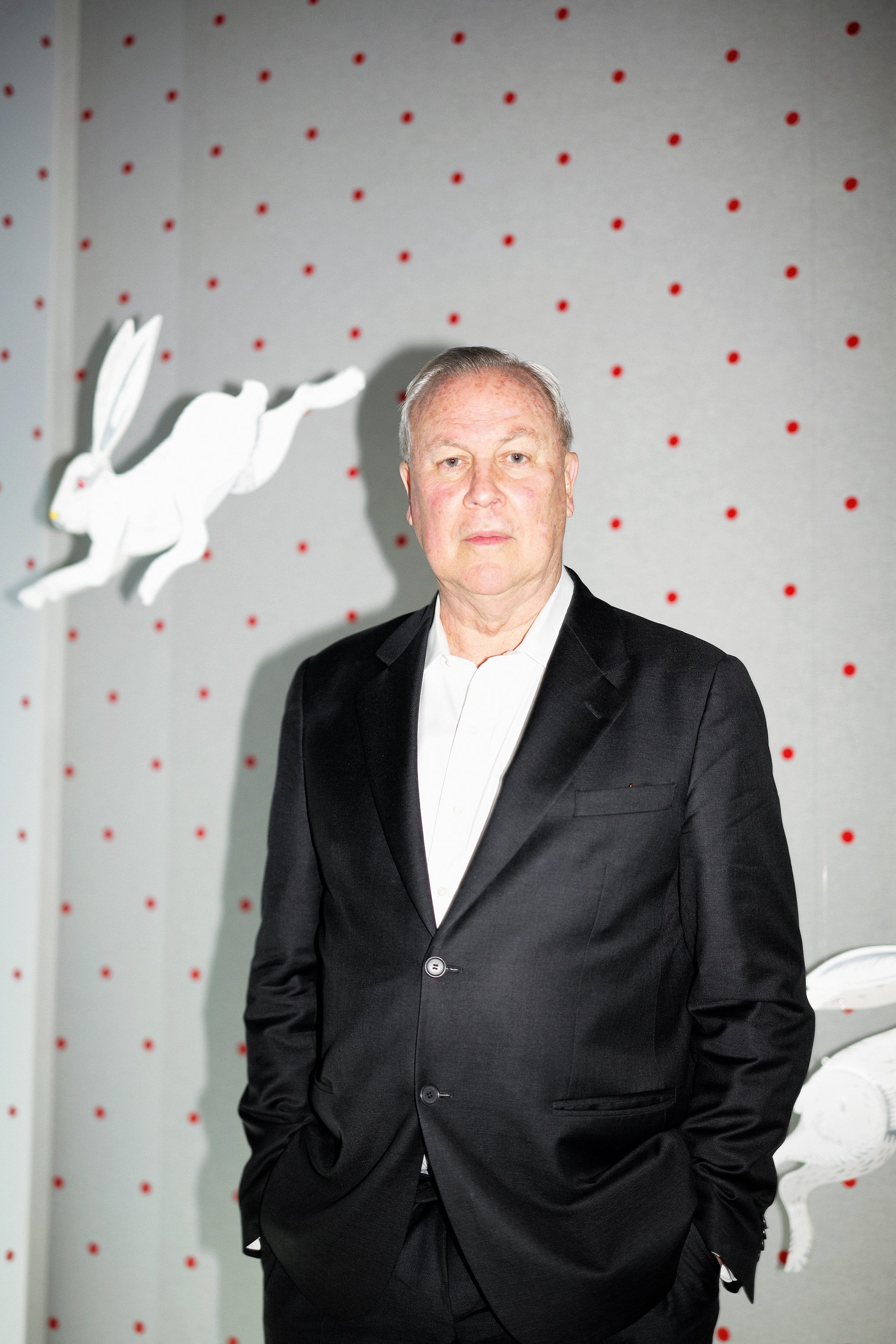

A Venetian Rendez-Vous with AXEL VERVOORDT

|Robert Grunenberg

Every two years, the international art world weaves through a network of Venetian canals, consuming a plethora of exhibitions that are nearly impossible to navigate in their entirety. Yet Axel Vervoordt’s exhibition “Intuition” at the Palazzo Fortuny, a gothic mansion in San Marco, was certain to appear on everyone’s to-do list. Having defined a rough-hewn aesthetic that has traveled from his compound in Belgium to the homes of Kanye West, Bill Gates, and Calvin Klein, Vervoordt is known as a master of atmosphere. Composed from a variety of periods and location, “Intuition” is a manifestation of a concept that Vervoordt once shared with 032c: that all art has been contemporary.

For 032c, Robert Grunenberg met Vervoordt at the Palazzo Fortuny for a guided tour of the Wunderkammer filled with contemporary art, old masters, Eastern design as well as minimalistic furniture.

Robert Grunenberg: Mr. Vervoordt, you have been working on the concept of the exhibition for almost two years. How do you set up a mega show like this?

Axel Vervoordt: We work with think tanks, mathematicians, scientists. The art comes out of studying the concept. Then we make a synopsis of this study and together with all the curators we make a list of artists and old masters that best represent the several ideas we want to express. This synopsis is sent to a list of contemporary artists and they can present a work of art to us, which is then evaluated within the group of curators. In this way, we compiled about 350 works of art, of which 15 commissions and 5 performances were created during the opening days.The installing in situ took a month, which was hard work as we had to find a place for every single art piece. Generally, we want every piece to receive its honor and enough space, so it can unfold itself. Overall, 20 people worked on the show. Everyone was aligned and understood the crucial attitude of asking the artworks where they want to be – when do two pieces make each other stronger through their placement and when do they take away from each other.

Your gallery is based in Antwerp, where you will open your foundation at a new site at the end of this year. You live in the castle of ‘s-Gravenwezel outside the city – a place that also functions as a showroom for your art and design philosophy. Where do you discover these signature pieces?

I have been collecting since more than 40 years now and I only bought what I liked, never with a specific client in my mind. From the beginning, when we lived in the Vlaeykensgang in the center of Antwerp, we didn’t want to have a separate shop, we lived among the things that were for sale. I still travel a lot and my son Boris is constantly touring around the whole world to find artworks and furniture. Then we have a team of people overlooking the art market, following auctions and other galleries.

The show in Venice is titled “Intuition” – what is your take on that?

The show is about freeing ones intuition, trusting and embracing it. Life throws many things at you and you have to make decisions everyday. For an artist, this can be a technical or an aesthetic question, for which there is no set of reasonable answers. You have to listen to your guts, and most of the time, that is where true creativity occurs.

You bring together things from very different backgrounds into a harmonic environment, which reminds me of the idea of a Gesamtkunstwerk. Yet there seems to be a connection between the different things. Is the x-factor in all of this intuition?

It’s always feeling. And yes, intuition, which I believe comes out of total freedom. I don’t believe in style rules. It’s just listening, seeing, feeling, and a kind of humbleness. I prefer the more hidden qualities, generally. I don’t want things to show off too much or be too loud. I like it more silent. The things I work with are very rarely negative art that is political or that follows a moral compass. I prefer things to give a good example of how life is always interesting. It’s searching for the universal. That’s why it is important for me to mix the old and the new and not be limited by time.

Is good taste something you can learn?

I think to make something beautiful and pleasing is always a bit dangerous. I try to avoid it. I think it’s fantastic when it is pleasing, but more importantly, for me, is that you feel the spirit and that you create a positive tension – a positive connection between the objects and yourself. For myself, I try to be as little present as possible in the sense of putting forward my own style. I prefer to have no style. It’s my way of doing things. I love doing simple things in a great way.

What makes something good art?

There are museums of contemporary art, and there are museums of old art, but for me, art is art. Good art is timeless. I always try to bring the old and the new in contact with each other. In the life of a mayfly, one second is long. For you and me, a year is long. But for the stars who live billions of years, 500 years is nothing. Our general concept of time is limiting as time itself is relative.

Within your exhibitions and interiors, you create unique worlds. You break rules of time and space by crossing historical periods, cultural and geographic borders, similar to postmodern opera. Is opera an inspiration to you?

Music is important. The exhibition on the second floor at the Palazzo Fortuny has music, which was especially composed for this space. The singer followed a lot of our discussions surrounding intuition and she made the music on that basis, which became something like sound architecture. It binds all the art together.

The locations you like for shows are not the typical museum spaces. What do you think of the concept of the “white cube”?

A white cube requires a lot of attention. I think you have to focus the spotlight on the painting – the white takes all the light and gives it back. I personally sometimes think that the spiritual qualities of a work of art are better when the walls are more earth-like or like a shadow. More and more, I have come to like walls that seem like a shadow. But it doesn’t matter. For some art, I prefer the white cube. I’m not against it. But I wouldn’t like living in a house like this.

I grew up mostly seeing art in white cube spaces. It’s so dominant in galleries and museum spaces and so connected to the perception of art, that it’s almost hard to recognize something as art when it’s not situated in the white cube.

It’s a dogmatic minimalism, which I don’t like. I don’t like the idea of dogmatic because I think it’s like freedom. I think it’s important things come out of the feeling. You have to feel with your eyes as well, not only look, but feel with them. Art is like a teacher. If you live with art it’s like living with great friends. You learn from it and it broadens your view and it adds another dimension to life.

So is art more about feeling or understanding?

Both. But, for me, intuition comes first, understanding later. My intuition will first say, “Ouch, I want to be connected to it.” Or I’m afraid of it. And then the understanding might sometimes change your idea, but not very often.

Besides objects and installations, you started working with the performance artist Marina Abramovic for this exhibition. How does her artwork fit in?

Marina is radical. Before I knew her, I was scared of the things she was doing. But what I love about her is that she is a very strong person who views pain on another level. She is a very important artist. In terms of performances, she might be the most important artist. I think she teaches how to perceive limits in a broader and wider sense.

In one way, you transform a place like the Palazzo Fortuny into a world of your own. On the other hand, you install work sight-specific. How do you balance that?

Yes. I respect the architecture of Palazzo Fortuny and Venice and its history. I also respect the figure of Mariano Fortuny – the artist, designer, and collector who lived in this palace and turned it into a ‘place to be’ for collectors, musicians, stage directors, and artists in Venice.. It is our own exhibition, but it’s quite important that all these elements are present and not hidden. For instance, at the Palazzo we built the pavilion of Tokonoma. It’s based on Japanese concepts of Tokonoma. „Toko“ means platform and „ma“ means framed into this. In a nutshell, this is how we work.

You said you don’t have any rules on style. Could you nonetheless name a few pillars of your work?

For me, everything needs to be real, because I believe in the energy of real. I prefer things when they are honest and not trying to copy something else. It’s a different view. I have always been interested in beauty found in nature’s artistry. My passion for humble objects let to my fascination with unconventional, avant-garde art movements such as abstract expressionism, ZERO and Gutai. Many artists like Lucio Fontana, Gunther Uecker, Jef Verheyen, Yves Klein were also very much interested in Japan, not just for the judo, but for many philosophical reasons, I discovered. It’s about understanding the void and the connection with the earth and the cosmos, bringing one closer to the very essence of existence.

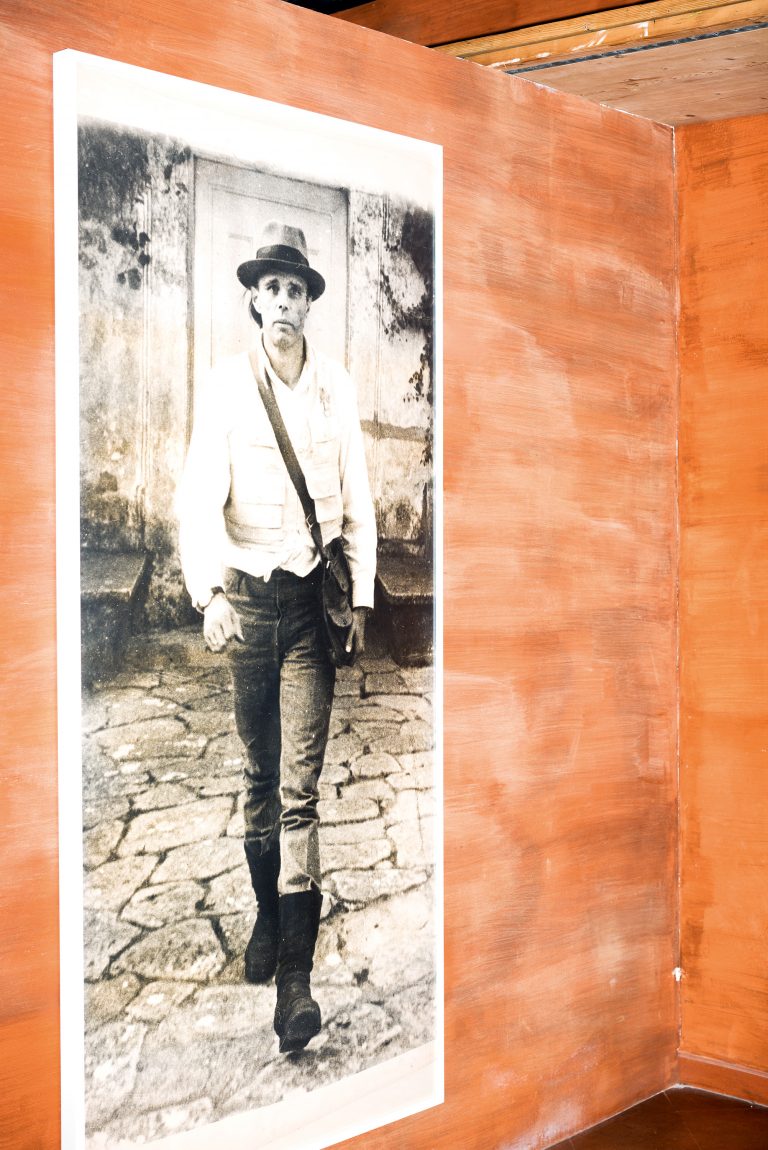

A lot of your artworks – your furniture and interiors – work with the idea of patina, of surfaces that have transformed and altered with time. What do you find fascinating about patina structures?

It’s the beauty of age and imperfection. Time itself becomes the artist, because it is able to transform things. What’s missing in the new is a story. There are no cuts, no traces of use, no damage. But time oxidizes things and gives material a new skin. It’s kind of an active love. I love these old things, even if they were not meant to be beautiful and have been used. It has something so real.

In a globalized world that is becoming more and more digital, patina reconnects you to the materiality of objects. It has a therapeutical and soothing quality because everything is so abstract in a digital world.

It’s also a matter of respect and love for the material, like respect for the earth and respect for very simple things that we are surrounded with. When you pay respect to these things, your life gets more interesting.

Next to the historic locations like the Palazzo or your castle, you also work with newly built homes of people like Calvin Klein, Robert de Niro, or Kanye West. Why do you think they want a home created by you?

They contact me because they like to connect with real things. They need it because they create fantasies for others. And for them, it’s extremely important to come back to earth and connect with it so they don’t continue living in a fantasy. They want to live with real things.

Credits

- Interview: Robert Grunenberg

- Photography: Christian Werner