In Media Res

Billionaire publisher, “main German friend” to Andy Warhol, patron of German media philosophy, and media theorist in his own right: meet Dr. HUBERT BURDA.

I became aware of Dr. Hubert Burda in November 2010, when a Berlin-based lady I know advised that presently she would spend two days in Karlsruhe, a tiny University town in southwest Germany, owing to work-related obligations.

For the lady is personal assistant to Professor Friedrich Kittler, Humboldt University’s oracular Media Scientist, who had been invited to participate in the launch of a communications theory book, In Medias Res: Ten chapters on the Iconic Turn, by multi-billionaire media mogul/poetic intellectual, Dr. Hubert Burda. Professor Kittler is interviewed in the book, and over the previous two years his professorship had been underwritten entirely by Dr. Burda – theirs is the most novel of friendly relationships.

Philosopher Professor Peter Sloterdijk calls Burda an “Upper Rhine Baden surrealist.”

Humboldt had fired the eccentric professor in 2008 over an aggregate of peculiar mental abrasions with fresher-faced colleagues, whereupon Dr. Burda established a private program that extended Kittler’s intellectual services and perpetuated the growth of his youthful following. Established from the beginning as a two-year grant, the professorship attained its prescribed end in February 2011.

I wrote to Swiss novelist CHRISTIAN KRACHT in Buenos Aires:

Over the past week, a big shot named Burda has been in contact with my erstwhile lady companion, being that she is Friedrich Kittler’s PA and they attended the Burda’s Karlsruhe book launch together. The following morning, Burda purchased an Air Berlin coach ticket and tailed them back to Berlin, phoned the lady, known for her high ceiling and caboose, and 12 hours later they ate lunch. Consequently I find her appealing again. The spectacle frames he wears in photos appear remarkably similar to my own reddish Nepali ones, and he is married to the grandniece/step-grand-daughter of Furtwängler.

Christian replied:

Yikes! I think I know him! First name please!

I answered:

Hubert.

Christian remitted the following words with mesmeric attachment:

Ah, yes! Hubsi has been awarded this medal (the order of merit) by Italy.

“Note the SPQR eagle beaks.”

Resolving to interview Dr. Burda, I first wrote to Nick Currie in Osaka, a seasoned 032c contributor:

Dr. Hubert Burda seemed to be in contact with the lady I was mating and abandoned – he texted during her time in my custody, and I witnessed her enthused eyes dart in the glow of her electronic doodad. I remain unaffected by these events, but assuming he declines my 032c interview request, I shall mine a stash of windy notes I’ve composed to generate his answers, which shall be reworded to suit the questions and his circumstances – e.g., rather than an enthused description of my online poker-playing flatmate in Neukölln, he could digress into an unhinged reverie about his online coin-dealing daughter in Lausanne. His wife Maria Furtwängler, the sexy physician and movie star, is a 2nd niece of you-know-who’s favorite conductor.

Shortly thereafter I was in receipt of In Medias Res (Dr. Burda’s book in German, despite having a Latin title) and the new English edition The Digital Wunderkammer. Both were published in Germany by Fink Verlag, along with other recent materials by and about Dr. Burda, Europe’s society tabloid kingpin who centers his egghead pursuits on a notion that he calls “Iconic Turn.” Over the past decade, he has devoted himself to questioning how digitization has altered the meaning of images for the media company he inherited from his father and developed significantly. Iconic Turn refers, in essence, to a change in the past decade in our perception of images.

I became ardently immersed in the works proffered. Below is a sampling of my notes, which in their original form include the occasional diagram, a flourish that I am rarely moved to attempt:

* Manfred von Ardenne invented TV, 1933.

* How does Burda echo Nietzsche? By recalling Gangasrotogati – moving with the gait of the Ganges – on pp. 48-49: Festina lente, the motto of the Roman emperors, became a famous emblem. It means, “Make haste slowly,” and is represented by the symbol of a dolphin and an anchor. It is clear from the image that one is meant to associate the swiftness of the dolphin with the stead-fastness of the anchor.

* Lord Weidenfeld: “From Munich to Silicon Valley to Jerusalem: Hubert Burda’s Road.”

* Hubert Burda on Steven Spielberg: Hardly anyone can match Steven Spielberg in intensifying narratives so that they become visual parables of human existence. He’s a brilliant story-teller. There are images in his movies Schindler’s List and Saving Private Ryan that penetrate deep into our consciousness with an almost physical immediacy.

* Steven Spielberg on Hubert Burda: I believe in the synchronicity of moments in time. This is how I would characterize my meeting with Hubert Burda five years ago. This passionate philosopher, publisher and devoted humanist has become a friend and partner in our joint pursuits of a more tolerant world and a better future for our children and theirs.

* Hurbert Burda on Steven Spielberg (II): When Spielberg told me of his plans to set up the biggest collection on film of eyewitness accounts of the Holocaust, I was immediately won over. I regard it as a historical obligation to contribute to this project.

* “Here is someone who … has succeeded where only few people succeed: in making his dreams come true.” – Jürgen Todenhöfer, Deputy Chairman of the Management Board of Directors at Burda Media Holding since 1990.

* Philosopher Professor Peter Sloterdijk calls Burda an “Upper Rhine Baden surrealist.”

* Guerlain sells its wonderful perfume ‘Vetiver’ in a new bottle: modern and no longer adorned with the beautiful, old, calligraphic letters, which are evocative of Marcel Proust, of the literature of the 19th Century, and which also evoke the lifestyle of the aristocracy and the playboys of the 1920s, when it was very difficult to obtain such a perfume, and very few people had it. Admittedly, the ingredients have not changed, but it is nevertheless very difficult – it has become new – because of the packaging, the frame, in which it is now presented. And it is, by this time, on sale in every drug store. The frame is thus an element of the brand, and the brand must be stage-managed via this frame, the lettering and the design.

[Not in the book: The newer version, which isn’t a far cry from the original, offers guys a classy and sexy cologne they can appreciate. It’s filled with earthy scents of tobacco, nutmeg and coriander, as well as citrusy accords of orange and lemon (www.guerlain. com).]

Without a frame, absolutely no kind of reality is possible. The view from a window is, of course, not a normal view. There is no view out onto the street that is not framed by some confined space – a hotel room, the apartment of friends, or one’s own home (p. 51).

* Burda, archeologist: I was at a lecture on Liberale da Verona when it first occurred to me how the copper engravings of Martin Schongauer migrated over the Alps into Northern Italy, where the image motif was adopted and built in to the Lamentation over the Dead Christ, which today hangs in the Alte Pinakothek in Munich.

* Re: Hanfstaengl, on a page illustrated with Renoir’s Young Woman Reading an Illustrated Journal (1880): […]And thus it became possible to include pictures in 19th-century newspapers. The centers for those lithographs were Munich, with Bruckmann, and Hanfstaengl, and Mulhouse, with Braun.

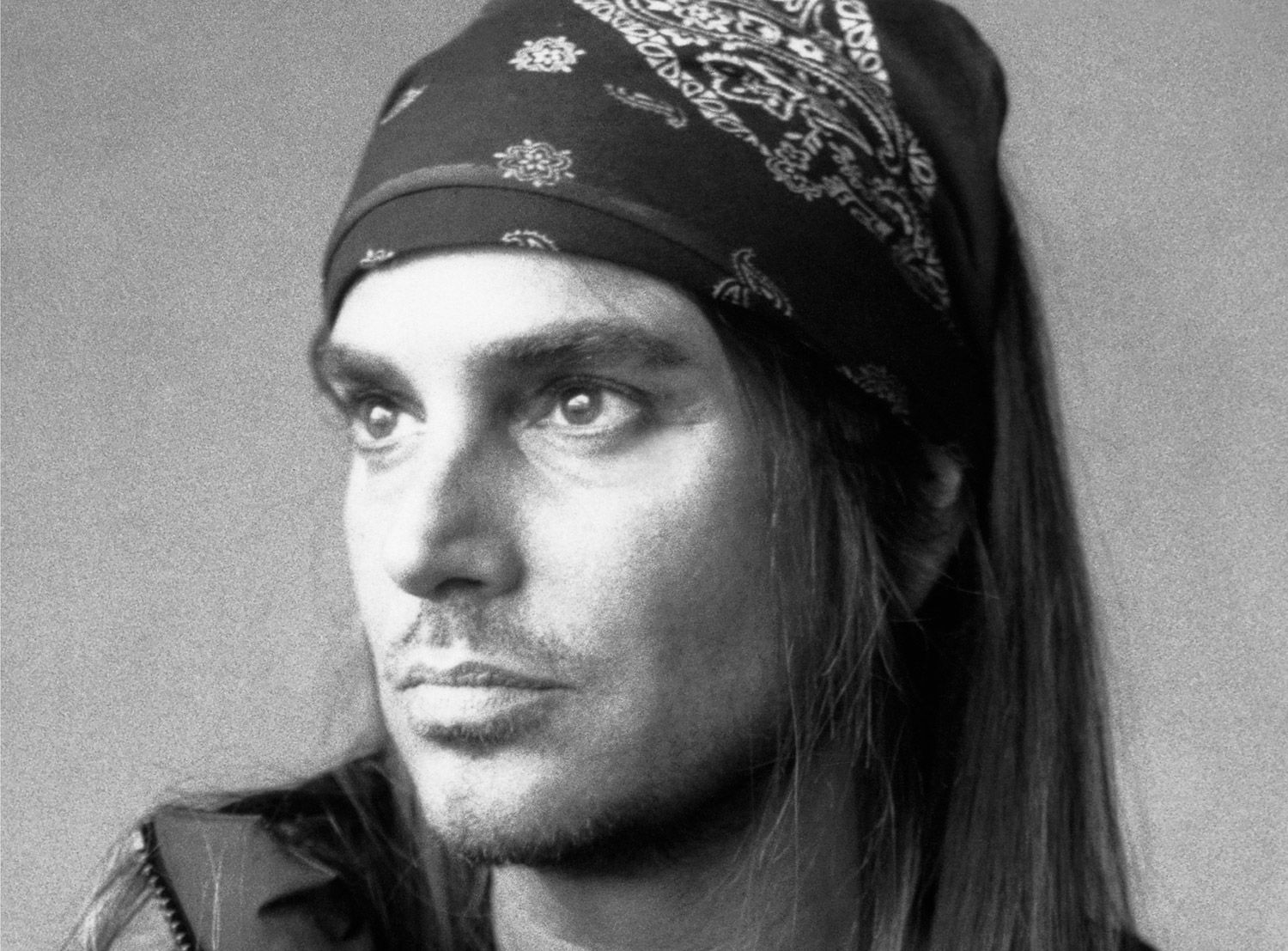

* Re. Hubert Burda’s painting Self Portrait (early 1990s): The white of the left eye is laid in white, mixed with minute quantities of green and blue. A thin scumble of darker blue is brought over the under layer, which, however, remains exposed in four places to create the secondary highlights. The veins are painted in chartreuse into the wet scumble. The iris is ultramarine, fairly pure at its circumference yet mixed with white and black toward the pupil. There are vermilion flecks near the circumference, tipped in gray over the blue of the iris. The principle catch lights are four spots of lead white, applied as final touches, one on the iris and three on the white, where they register with the four secondary lights to effect a glisten.

* Mathias Döpfner (2011 German Media Award: Media Person of the Year): I am a non-Jewish Zionist.

* “UNTHINKABLE” (chapter of Hubert Burda Media Holdings’ Map your Future: The DLD 2010 Book) / Interpenetration of the Hemispheres: It is important to be important.

On the morning of the interview I flew from Berlin to Munich and rode a train directly from the airport to Dr. Burda’s office. Even so, I arrived at Hubert Burda Media Holdings, a small assembly of buildings, 10 minutes late for the noon appointment. Many business people were standing outside, as an hour earlier a cupola had been sealed on top of a peripheral building, and they appeared to enjoy the excuse to not work – it almost looked like a party. Some of the men wore yellow helmets, which made me wonder: How can you wear a protective helmet without guilt, while the bulk of your peers remain exposed to danger? My thoughts struck upon a more constructive note: So, this is where in a few moments I’ll encounter Europe’s Murdoch-Warhol-Jung, ideally without being reverse-paparazzi’d.

On walking into what appeared to be the main building, I was quickly ushered by a lady named Sandra from the lobby reception area to a 5th floor debriefing room where I was advised to leave my coat and hat. Across the suite in a sun-drenched corner room I was introduced to an athletic 30-something, Nikolaus von der Decken, Direktor Konzernkommunikation, who – notes and digital recorder in hand – made haste to escort me through two keypad-protected doors and up three flights of a private concrete stairwell. Nikolaus took a deep breath and said, “Now, I’ll enter the room first.” I agreed, and together we entered a sprawling, old fashioned, impressively spartan office room occupied solely by Dr. Burda, who was seated behind a massive oak desk in front of a tall row of windows and sky

Dr. Burda did not exactly smile as I approached but lifted from his desk and, conducting himself in a courtly manner, padded round with powerful steps to welcome me and shake my hand. Nikolaus motioned for us to sit together on an L-shaped couch near the door. A copy of In Medias Res and The Digital Wunderkammer each lay in repose, poised midstream along an oval coffee table. Nikolaus sat in a chair.

We began to discuss an almost mutual friend – 70-something Dr. Burda knows the crotchety 90-something Christian Kracht, who was General Manager at Springer Verlag during its glamorous 1960s heyday, whereas middle-aged me knows middle-aged Christian Kracht, novelist. The Christian Krachts are, like many fathers and sons through the echo of time, mutually exclusive. Still, Dr. Burda and I were each after his manner able to say, “Christian Kracht is my friend.”

HUBERT BURDA: Christian Kracht [Sr.] was very sensitive towards magazines and newspapers, and I admired him. When I was about thirty-one, I had a strong debate with my father about magazines. He stopped me making magazines; they were too revolutionary for him. So I went to see Christian Kracht at Springer in Hamburg and told him, “I’m not happy in my company. Why don’t we build a publishing house together?” He told me, “No no, Hubert. You go back to your father’s company.” And this was a very decisive moment in my life. [Kracht] was very creative – like a dancer, of sorts.

So, those are our mutual friends. But now I would like to talk about the starting point for my book, In Medias Res, which was about ten years ago, when I initiated a series of university lectures – twenty-four lessons from the most important specialists. Famous scientists or artists would come and give talks about the Iconic Turn. In the book there is an image from ten years ago of a group of people gathered around a piano in China taking pictures with their cell phones – and it looks, formally, just like the images you are seeing coming out of Libya today, with people gathered around tanks.

DAVID WOODARD: This is in your book, and yet it also happened yesterday.

Yes. Now everyone is taking pictures that in one way or another will be transmitted to the rest of the world. That means the Iconic Turn is here, every day – it is Facebook, it is Twitter, it is the iPhone, it is CNN. Ten years ago, we couldn’t think of YouTube, we couldn’t think of the social networks. So when we started the lectures in 2000 it made an incredible impact at the university. We sometimes needed two halls of this size [points to picture of a large hall]. I think when Lord Norman Foster spoke we got several thousand people. And at the time of the series, whenever I was in an airport or elsewhere, I studied people – I applied the theory to my surroundings. So in the book you find observations with very practical and day-to-day information. For instance, in the case of Dürer’s etching, Erasmus of Rotterdam (1526), the distinction between the figure and the imago still existed. Nowadays the trivialized term “image” is applied to everything – one speaks of a company’s “image,” and so forth. So for about ten years I recorded these observations on tape, and later had them transcribed. From about, I don’t know, 2,000 pages, we eventually arrived at 20. And finally I thought, aha! This is the total change in media that is happening right now …

You began around 9/11.

Yes, 2001, and in about the same year I came up with the ten chapters. I started with the first one, “The other view through the window.” Here, frame/window meant television. And if I were to do the same thing this year, I would arrive at Facebook. Social media is the next step.

Speaking of social media, I recently watched a great YouTube clip in which you’re socializing with Michael Jackson. You describe him in his presence to a third party, using strikingly human terms, observing his humanity, his purity, his wavelength and vibrations. I found your argument convincing – the clip appears to be a VHS transfer from a time before the digitization of human qualities, which is what we have with things like Facebook. Because you observed Warhol at work, I imagine you found that he too was a very pure human being. We are living in a time when it is suddenly possible for a much broader spectrum of the species to focus on and identify what constitutes individuals’ humanity. How do you see the influence of the Internet on the future of humankind? Up until 9/11 it was only a tiny elite of the most talented, and the cleverest, who enjoyed the possibility of transmitting their likeness to the world. That this would change, or turn, so quickly and drastically seems certain to have a profound effect on human thought patterns and conduct in the emerging generation. Let’s survey, through your eyes, the horizon of post-Facebook consciousness.

I think you can compare it to electricity, which started in the mid-18th century, with Dalibard, Galvani, and its spread could be compared with Microsoft, with Explorer, but first of all with Windows. Suddenly, you could turn night into day, with Werner von Siemens in Germany, who could be compared with Steve Jobs. One invention after another was then being done – Bell and the telephone, Marconi’s waves, Lumiere …

Helmholtz …

… and then Steve Jobs, and of course now Facebook. And Google has been an incredible invention. We still have electricity, yet we do not feel it anymore. Most things we do depend on it. We are like fish in the water of electricity. The web will be the same in ten to twenty years from now. The next steps will be cloud computing, the further development of mobile communication. The new devices are really small. [Walks over to desk, produces iPhone.] And the applications on it do everything. Here’s one for the weather. It’s just incredible.

[Earnestly.] I am recording, transcribing and writing my entire article about you on an iPhone.

Everything. So, if you ask me about the Internet, it is there; it has changed the whole social structure with which we communicate. Change is my whole business.

That is a very concise sentence.

[Clippedly.] Yes, of course.

Look at the top of the Kittler chapter: “There are no clouds on Mount Olympus.” This must be a cloud computing reference.

I would like to mention “celebrity culture.” Warhol did a huge painting for my company. I once gave it to a show called Munich Images. At the opening reception I came up with a speech about celebrity culture. I mentioned the Emperor Augustus, who came up with movable pictures. He was the first to put his portrait on a coin, and from there on everybody in his entire Roman empire knew his face – even the idealization of his face, with a certain imperial nose. Now you can see the importance of celebrity culture anywhere – the importance of movies, the huge screen, the great poster, Marilyn Monroe, and so on. And at that point Andy Warhol came up to me, and he spoke to me like you speak to me about your magazine, 032c – he spoke about his magazine Interview. He wanted to get people famous, like you now do with me. [Laughter.] He was very, very kind, you know. He was a very shy man. And I said, “You are a genius.” And he’s now among the most famous persons in the world. This was in 1973.

Around the same time that Interview began.

Yep.

Bunte, which you publish, seems closer to what Warhol had in mind for Interview than what Interview itself became. It is my view that Bunte is more people-oriented than Interview – it enjoys a more profound sense of nothingness, the ultimate quality Warhol aspired to. I think what he wanted was a magazine that would germinate new cultural figures and their ideas, while in reality it became more of an ingravescent gloss-over.

He influenced me a lot, because in those days magazines were reporting on many topics that had nothing to do with people – health, international reportage from the South Pacific or other countries, and so on. I reduced it, and now it is a formula that describes German society, every week. Interesting people are show people, television people, sports people – people who want a notion in real life.

I read The Warhol Diaries when it came out – he talks about you in it, doesn’t he? This is essentially the Holy Bible of our age, or at least of the period from the year it appeared until 9/11. I haven’t consulted Warhol’s book in maybe 14 years, but you were his main German friend, weren’t you?

Yes. We got acquainted through Bruno Bischofberger, the gallery owner. [Andy] loved Switzerland, especially St. Moritz – he loved to stay there, he loved the palace, he loved the mountains. And then he came to Bavaria, and he loved Munich very much. That’s why he did this painting. In 1983, about four years before Warhol died, I gave a portrait he had made to the football player Franz Beckenbauer. It was a wonderful summer day, and we were at the Hotel Bayerischer Hof, and he liked it very much. Of course there have been other Germans to commission Warhol portraits. But you know, as someone who studies art history, I knew from Dürer and others that the portrait is something very much related to traditional art. In modern times there has been no real new genre of portrait painting. You had the Impressionists, you had Picasso, who was a catastrophic portrait painter – nobody wanted to get a portrait from Picasso, especially the surrealist ones. In the early days, he was quite good. The Stravinsky drawing is very good; the Diaghilev drawing is very good. But he took those from photos; he projected them – you can find the photos today. I wrote an article for the art historian Horst Bredekamp on the development of the art of the portrait.

It’s a very fine essay – I read it twice.

So when I saw Warhol, I thought, “Oh my God, that’s the way to do it.” Warhol brings photography and painting back together – this is the combination for Warhol, and for Gerhardt Richter. Andy was born in 1928, Richter in 1932: they’re more or less one generation. When I saw this kind of portrait I was convinced that this was something that you could show to other people, so I took my telephone and called this person and that person and I said, “Hey, your daddy is turning sixty, here is a nice present for him.” It was $25,000 for the first one, and the next ones were $5,000 each after that. My father had five more.

Warhol seemed like an angelic Eastern European peasant, constantly searching for new buyers. We met a couple of times, though I hardly knew him – he was pathologically gentle.

You were born in which year?

I was born in 1964. I lived in New York in the ‘80s. It’s great to be sitting with you, because here is something that I ponder every once in a while: a funny thing happens now with portraits – post-Warhol portraits either quote Warhol, or find another way to flounder, as if there hasn’t been a significant advance in society portraiture since the 1970s.

Cindy Sherman – taking oneself as a subject.

Self-portraiture has dominated and devoured society portraiture with ruminant churnings of Iconic Turn …

Yeah. Everybody is putting himself on Facebook with ten portraits a day. I cannot say what the next generation – your generation – will consider. For me, we did our job with Warhol, with Richter – Joseph Beuys, not so much. Of course Beuys was taking pictures of himself; he was performing as a piece of art and took pictures of this. By the way, you always have to think about the frame in which a work is created. That’s why in the book I did a chapter on the frame [“Image and Frame”] – whoever has no frame for the images will always speak of an image torrent. And the frame, for the moment, is given over to social networks.

There is a German cultural figure based in Berlin-Treptow, Friedrich Kittler, whom I’ve found to be amply engrossing. We’ve met a couple of times – I attended his 64th birthday party and gave him a package of Elisabeth Nietzsche’s Yerba Mate. It is unusual for a figure in Germany – intellectual, poetic, or otherwise – to exude unbridled charisma. But Kittler has a worshipful following among his pupils. There is something oracular, irrational and dreamlike about his proclamations; such as that present day Germany is Ancient Greece manifest, and that a profound spiritual connection exists between those cultures, making them one. In 2007, I attended a lecture that Professor Kittler gave on Ancient Greek musical instruments and mathematics, held at the Musikinstrumenten-Museum Berlin. He would sometimes say something removed from what he was lecturing about, producing an elegant mental short-circuit. For instance, after describing a dissonant interval in the Lydian mode, he concluded [in deep, resolving tone], “And so, after a reverie, humankind finds always its lot.” So I was happy to see his inclusion in your book.

And Kittler is a good friend of mine – I sponsored a chair at the Humboldt University for two years. He is not mainstream. Historians of music come and say, “But he did not write his thesis on Palestrina.” And all the professors of philosophy say, “But did he write a thesis on Kant or Heidegger?” No, Kittler is a mixture: Kittler is in between philosophy, the history of music, computer science, and media theory. That’s why he is completely outstanding. We have some fundamental heroes in Germany, really outstanding people on the level of Deleuze, Derrida, Lacan, Bataille … Among these are Bazon Brock, Friedrich Kittler, Sloterdijk, Bredekamp, or Hans Belting. These people will last longer than I will in this book. In 50 years, each of them will be known as people who had been very sensitive to changes of the media.

I want to talk about your art, because the Die Zeit portrait of you in December opened my eyes to the fact that you paint. Do you see your work as being integrated? You were, until recently, the CEO of Hubert Burda Media Holdings, so this would engage the Apollonian mind, yet at the same time you have pursued collaborations and friendships with these five German intellectual figures. For example, Bazon Brock, whom I think you named. These seem like different thought processes – running a two billion euro corporation, and being deeply engaged in cerebral intercourse. But maybe, for you, they’re unified in some way.

I mean, these are two sides of one medallion. On one side you have a portrait of an emperor, and on the other side you have an animal or a coat of arms. Both mean Habsburg Emperor, but Maximilian is on one side, and on the other side it is still the same coat of arms. I have been this coin: on one side you have conducting a company, but how can you conduct a company when you are not sensitive to new technologies, wishful art, or poetry? In my mind, it is not possible. Poetry is so much of how I think, you know. I jump from the two sides of my brain. The left side brings me back to tell me that it is 1:30 p.m. while the right side says, “Oh my God, we could have five or six more hours talking to you, because it’s just like in a movie – it is like conducting music!” And the real art of life is to combine these; to combine the incredible universe of the fine arts – of Titian, Raphael, Shakespeare, Keats, Shelley, Michaelangelo – with the instinct of being a good businessman. In my opinion, if you live only in one world, you must be a great genius.

There is very much a unity, then, in how you view your combination of endeavors. When you are working with Kittler, you are not forgetting about the CEO-ish part. You are a whole unit – really not putting on various hats.

Look, when I was Editor in Chief [of BUNTE]—I was 38, 39 — and the poet Handke came to me, and I said, “Come with me, stay one day with me.” At the end of the day, he said, “You know? This is like driving Formula 1. What you are doing is like driving a racing car. If you want to be killed in three or four years, continue. You will be dead; there is no chance for you.” This was when he came up with the book known as The Slow Return – 1979, 1982. The Slow Return showed him up in Alaska – Yukon River – and then coming slowly, slowly to New York, where he nearly became half crazy writing this book. Then he came here, and he stayed in the house of a friend of mine for a couple of months. And then I understood that I at least must manage two speeds – one, the fast track, and the other one must be without business, without speed, and this was the moment I came back to painting. When I was very young, I wanted to become a painter – the compromise in the family was art history. My father was right, I would have been a very average painter.

Uhnnn huhnnn.

So I try to get one week, two weeks, and last year for the first time, about three weeks off work, and then you reduce speed. I don’t need meditation, I don’t need yoga. I start writing or painting. Music – I like it, but of course Maria and the children got their talent from the Furtwängler family, not from me.

After the interview, falling to Earth in an aluminum elevator, I reflected on young Furtwängler’s tremendous respect for the Viennese theorician Heinrich Schenker, and the entry that would appear years later in Schenker’s diary (1923): “Furtwängler’s Ninth yesterday was magnificent; but he still makes the occasional boner – the third movement was in arrears.” Outside the Burda complex, waiting to be motored to Schwanthaler-straße, I noticed a youngish man carrying his three-year-old son in his arms. Their pram had suddenly crashed to the asphalt because it was overloaded with groceries – a bag of potatoes, onions and other foodstuffs were rolling out. I strode over to offer help for three reasons:

1. None of us asked to be born.

2. The man’s hands were filled with his child.

3. I might be able to incorporate it into the article.

After placing the carriage upright and the groceries back into place, I felt like a messianic traveler, and the man thanked me. The odd thing was he didn’t look at me as he spoke – his gaze was directed slightly to the left of my head, so I too looked over to the left of my head yet didn’t see anything unusual there. I was concerned about him and asked if he were alright – he said that he was. I began to walk back to the taxi stand. Still unconvinced, I turned around for another look. The man was still looking into space over where my right shoulder would have been, with his boy wriggling about in his arms. I pointed a finger at the cupola and advised that he wear a hard hat. He didn’t exactly smile. Again I asked if he were alright, and like a robot he repeated the same words – as if programmed by the three-year-old. Seeing a young father behave this way made me uneasy.

After dinner, at the quarters of my Munich companions Manuel and Kyonghee and their genteel toddler Ulrich, I examined my notes from earlier and quietly reflected on Dr. Burda’s insinuation that, had Ms. Furtwängler been around, he would have introduced us. My attention focused in earnest on three principle notes:

* “The Representation of Power through Images” (chapter): Which images from victorious culture remain at the center of the Western lifestyle? For future centuries it will not be Pop Art or the first phase of abstraction with Jackson Pollock – it will most probably be film. By which I mean the new entertainment industry that emerged around 1930 in Hollywood, from Greta Garbo to “Sex and the City.”

* Hubert D. Burda, the new Aleister Crowley: The internal images move outward in order to come back transformed. That is the real artistic process. What is needed: energy and imagination, as a gift and a blessing (p. 151).

* “Celebrity Culture” (chapter): The process of turning an individual into a star is then undertaken by artists. One example for this, even before Andy Warhol, was Picasso (p. 161).

“Every man and every woman is a star.” – Crowley, Book of the Law (1904).

I felt compelled to send Dr. Burda’s book to Dr. Kenneth Anger, as the latter’s avowed masterpiece, Hollywood Babylon (1959), treats cinema as the 20th century’s new religion, and triumph over Christendom as modern history’s Iconic Turn.

The following morning, having petitioned Hubert Burda Media Holdings to deliver The Digital Wunderkammer to the Luddite Anger in his Hollywood lodgings, I penned the following note under separate cover, to which he never replied.

When it arrives, please see Dr. Burda’s interview with Friedrich Kittler, beginning on page 68. Until recently Prof. Kittler, known for a pronouncedly oracular teaching style, recalcitrant interest in/advocacy of Heidegger, and over the past decade an increasing conviction that present-day Germany is Ancient Greece manifest, taught at Humboldt University in Berlin – you might enjoy this, especially in light of your film, Ich Will! – which I find as compelling as that baked-crab/Brie/artichoke dip that one gets so jailhouse territorial about at an otherwise friendly buffet.

Secondly, have a look at the chapter “Internal images – external Images.” It reminded me of the Great Beast, what with its reduction of “energy and imagination” as the basis for all art.

Lastly, the chapter “Wunderkammer” suggests art historical/portraiture underpinnings of the internet, as if the latter were “Every man and every woman is a star” manifest – it whispers between lines that you should continue not having a computer.

By DAVID WOODARD