2Traps Supermax

|STEVEN PULIMOOD

STERLING RUBY is a one-man Bauhaus. Based in Los Angeles, he maintains an artistic practice in a range of media: from painting and sculpture to collage, from photography and ceramics to, most recently, clothing and interior design. From his studio—one of the city’s largest—emerge objects that seem to be fragmented ruins of the future, extracted from another world. They seem less the work of a single man than the remnants of a dystopian society. “Post-humanist,” “schizophrenic,” and “hyper-masculine” are just some of the terms used to describe his installations filled with brutal structures, phallic stalagmites, graffiti-filled canvases, gnarled ceramics, and other caustic inventions of form.

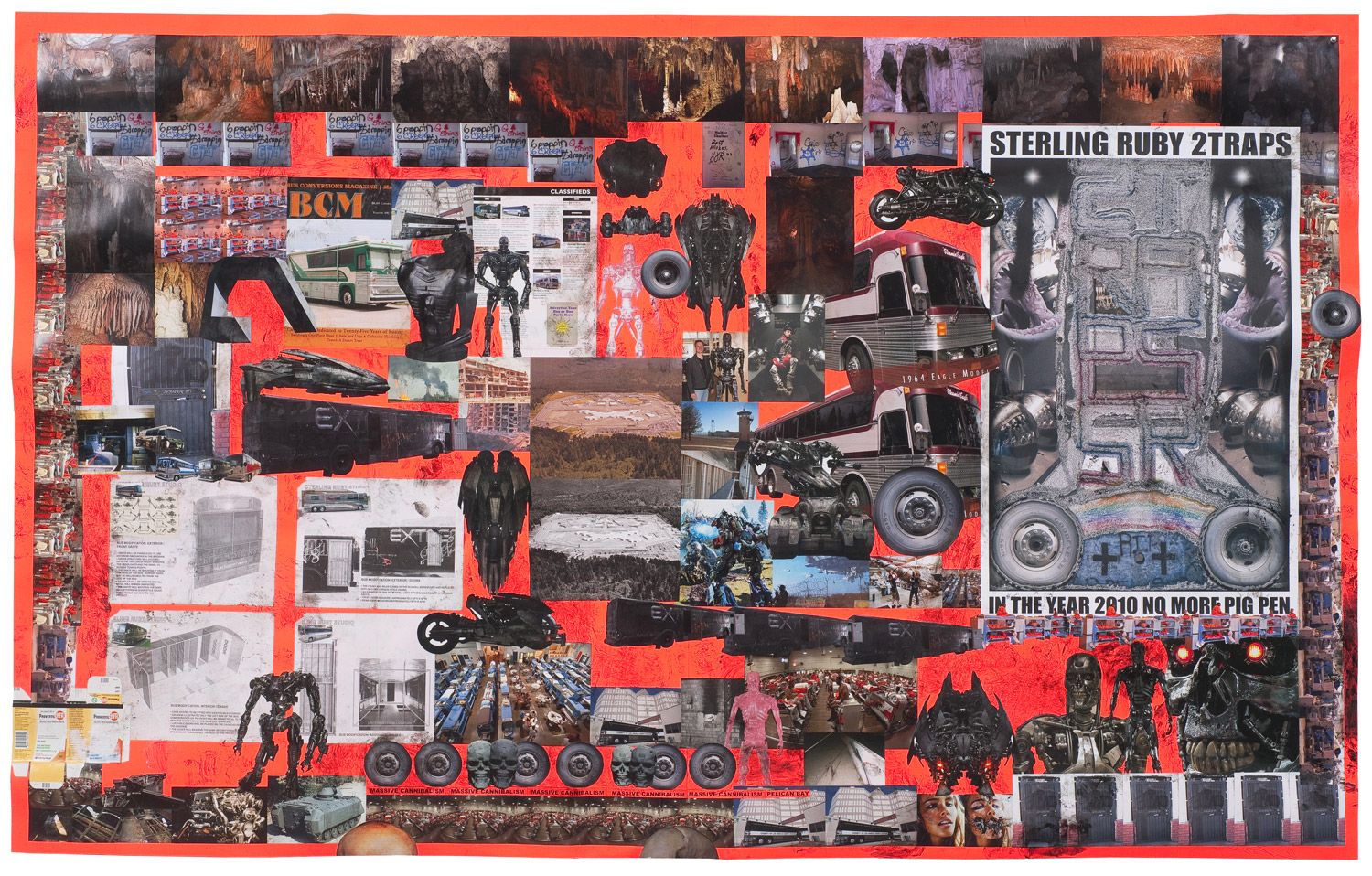

If his fascination with the repressive overtones of minimalism, architecture and the history of abstraction seem extreme, they are. Ruby’s practice is as intense as it is diverse, as visceral as it is unapologetically obsessive. There are few American artists of his generation that have so successfully exploited the limits of scale. Such boldness extends to his gallery program. He mounted a series of exhibitions entitled SUPERMAX (2005, 2006, 2008), and his latest exhibition in New York, 2TRAPS, consisted of two massive works—a stack of solitary confinement cages or “pigpens” and a modified party bus—which were transported from Los Angeles to New York on flatbed trucks. So unnerving was their tandem presence that I felt the need to ask him why he was interested in literal confinement.

I. How did your interest in repressive architecture begin?

I started thinking about the SUPERMAX prison systems, with their methods of incarceration without rehabilitation, as a beacon of the end. The SUPERMAX prison is architecturally constructed for control, and to keep prisoners in permanent lockdown. I look at SUPERMAX penitentiaries as being an allegory for a contemporary hell. This has led to works in which there is tension between an absolute repressive state and a liberated state.

Had you ever been inside a prison before?

Well, you can’t really take a tour of a SUPERMAX prison. To me the SUPERMAX penitentiaries are an inaccessible parallel world. They exist here and now, in America. There is no redemption, only a static state of detainment as opposed to correction. Not only is this a criminal phenomenon but it is also a social phenomenon. I also started thinking of it in terms of art: where art is and where artists of my generation are. They are largely against the wall with blasted concepts of what art should be, what art could be, what it could never be again.

Whether it’s positive or negative, there’s something morbid about a fascination with incarceration.

Absolutely—I don’t know that there is necessarily anything that I can say to convince people that doing something that opens itself up to negativity will eventually become positive. I do believe that exposing certain societal negativities opens up an awareness, which may at some point manifest change. I don’t know if it’s a morbid fascination, but I am continually drawn to this notion of being trapped as a kind of reversal. You might trap yourself.

Why would you put yourself into it?

Well, in urban or street terminology, the trap is something that you put yourself into in order to be covert, in order to not get penetrated— or, as a kind of bait: when someone else comes into your trap, you have access to them. The trap can also be a kind of protection—the trap is self-induced.

So 2TRAPS is not a jail?

There’s always turf warfare in urban environments with illicit activity. But it’s the same idea as the prison, that you’re building your own prison as a kind of isolation tactic. Or when in isolation, you don’t want to come out and you become so accustomed to it and fine with it that it becomes what you want. In addition to this I thought about the sculptures in the exhibition as time machines, slowing down and speeding up depending on whether one was inside or outside. I don’t want it to be too literal—it’s more abstract than that. But those are some of the ideas that fed into it.

There’s nothing in your work that is comforting—one could never spend time inside 2TRAPS.

Well, that’s not entirely true. I had a conversation with a well-known critic and fiction writer recently about Foucault’s influence. She took comfort in the practice of isolation and oppression … she was speaking of bondage. She liked the time that she had spent in “Pig-Pen” and “Bus.” There definitely are people out there who would actually enjoy it or derive comfort from it.

What would be the ideal environment for 2TRAPS?

“Bus” and “Pig-Pen” represent a whole new body of primarily metal, larger-scale sculpture that moves towards public work. I like the idea of making something of that scale and placing it in public where people would have unfettered access to it, having it act as an antagonistic form in order to see what kind of responses it would get.

One of the best things about walking through Richard Serra’s “Titled Arc,” for instance, is that it gives you that rare art-going experience of being between two walls, canted at an angle. It is one of the most disturbing things. Even though you are certain that this wall is not going to fall, rationally, you have this feeling that it could be fatal. There’s something about walking into your “traps” that has a similar depth. If Los Angeles invited you to put a piece into a public space, would it be a bit like “Titled Arc”? Whether or not he was intentionally trying to interrupt the flow of that plaza, it was an interesting experiment in frustration. And people really complained.

Over the past few years I’ve done many sculptures that have had inscribed surfaces, gestures on a surface that are not only mediated by me the artist, but also by the public that has access to it. I have seen Serra with that kind of tagging, and for me it informs that irrational feeling you just mentioned … it makes the work itself more vulnerable. I’ve always liked that antagonism that public sculpture provides. I’m not sure what I would propose for an LA public artwork to be honest.

The long stack of pigpens in the “2TRAPS” could have been derived from a planometric Sol Lewitt drawing, yet the untidiness of its surfaces dispels any notion of a minimalist heritage. Together with the narrow confines of the modified party bus (for Mad Max and his friends?) one not only feels like a slaughterhouse animal stepping inside of one of the many pigpens, but as Ruby says, they resoundingly appear as an “allegory for a contemporary hell.” Yet where are its victims, its proverbial damned souls? Their absence makes ruby’s motive clear: each of us who finds the curiosity to enter will experience some semblance of the futility of repression.

Is Ruby’s new departure into interactive environments and the potential of public art, yet another expansion of his vast output? More to the point: are we culpable in the crime? Or are we just accomplices after the fact? Surely we are not ourselves the victims, if we can exit at any moment? Cady Noland, the influential artist who abandoned her practice a decade ago, wrote chillingly about artistic deception in an essay entitled “Towards a Metalanguage of Evil” (1989):

“According to Hannah Arendt, one of the sights that struck Adolf Eichmann as being the most horrific was a perfect imitation of the Treblinka railway station. This imitation had been constructed for the express purpose of lulling prisoners into the mistaken impression that they had arrived at a safe and benign destination. The station had been built with patient attention to detail, with contrivances like signs and installations.

“In order to function effectively, the rules of the ‘the mirror device’ must be slavishly adhered to. Whatever the con, whatever the structure it takes, there are particulars, details which make each one unique and have to be filed in along the way. These are the nuances and shadings of the individual con, and they affect the success or failure of the con.”

There are pockets of political dystopia that still exist amidst the sanitized sanctity of our modern lives. Scattered throughout the world, graffiti-strewn sections of the destroyed Berlin Wall, for instance, exist as memorials to Cold War repression. Each is a standing shard, a stele of social division that when whole not only acted as a massive impediment to ideological advancement, but also as a literal blockade to the movement of people. somehow that fragmentary power of the Berlin Wall seems to infuse Ruby’s work, reflecting the energy of a failed police state. If we are willing to follow Ruby from the normative reality of our lives into an allegorical hell, as Dante followed Virgil, then his art invites participation in the con—not, however, without adequate warning.

II. There’s a severity in your earlier work, where colors seem to play a critical role.

I associate those colors with industry. Take orange, for example, which has to do with safety, with “caution.” Neon orange screams for attention, I used to see a lot of it growing up in Pennsylvania, especially around hunting season.

When you create work do you look for a certain element, a certain color, or something with which you deliberately want to draw someone in?

I would like to think that it comes from some kind of an innate sensibility, a completely unexplainable attraction to certain actions, colors, forms. I also think about what other artists have done. I think about playing off of what has come before and how things and ideas can be pushed past what has been done before.

There’s also a violent impulse to certain images, whether it is visible on their surface or not. I’ve seen drawings of yours where it’s almost as if you can see bloody finger prints, as if someone has been crushed. And there is a beauty there, a disconcerting attraction. They pull you in, but they do something violent to you as well.

In 2005 I did an exhibition in Los Angeles called “Interior Designer.” It was an assault on the masculinity of the art historical monolith. That was the first exhibition that had nail polish drawings. These drawings were very graphic, the nail polish itself seemed like a stand-in for an abstract expressionistic forensic study. The violent gestures in the work were also a repudiation of the art history and theory confronting my generation. So, formally, it was about toppling those historical monoliths.

Who made those monoliths, in your view?

Artists like Judd—who is someone I admire a great deal, but also somebody that I was forced to read exhaustively during graduate school. And in the past years there have been so many exhibitions on the importance of minimalism, minimalism as an object with no personification. Minimalism according to Judd’s writing seemed very authoritarian. Minimalist sculpture was always supposed to represent a discrete object with no personification; as if it had been made by itself. There were these rules and regulations that one would have to adhere to in order to think of things as minimal objects. The “Interior Designer” show was my segue between these non-personified monoliths and the gesture of cutting them down via someone’s surface demarcation.

Which is an act of castration, basically.

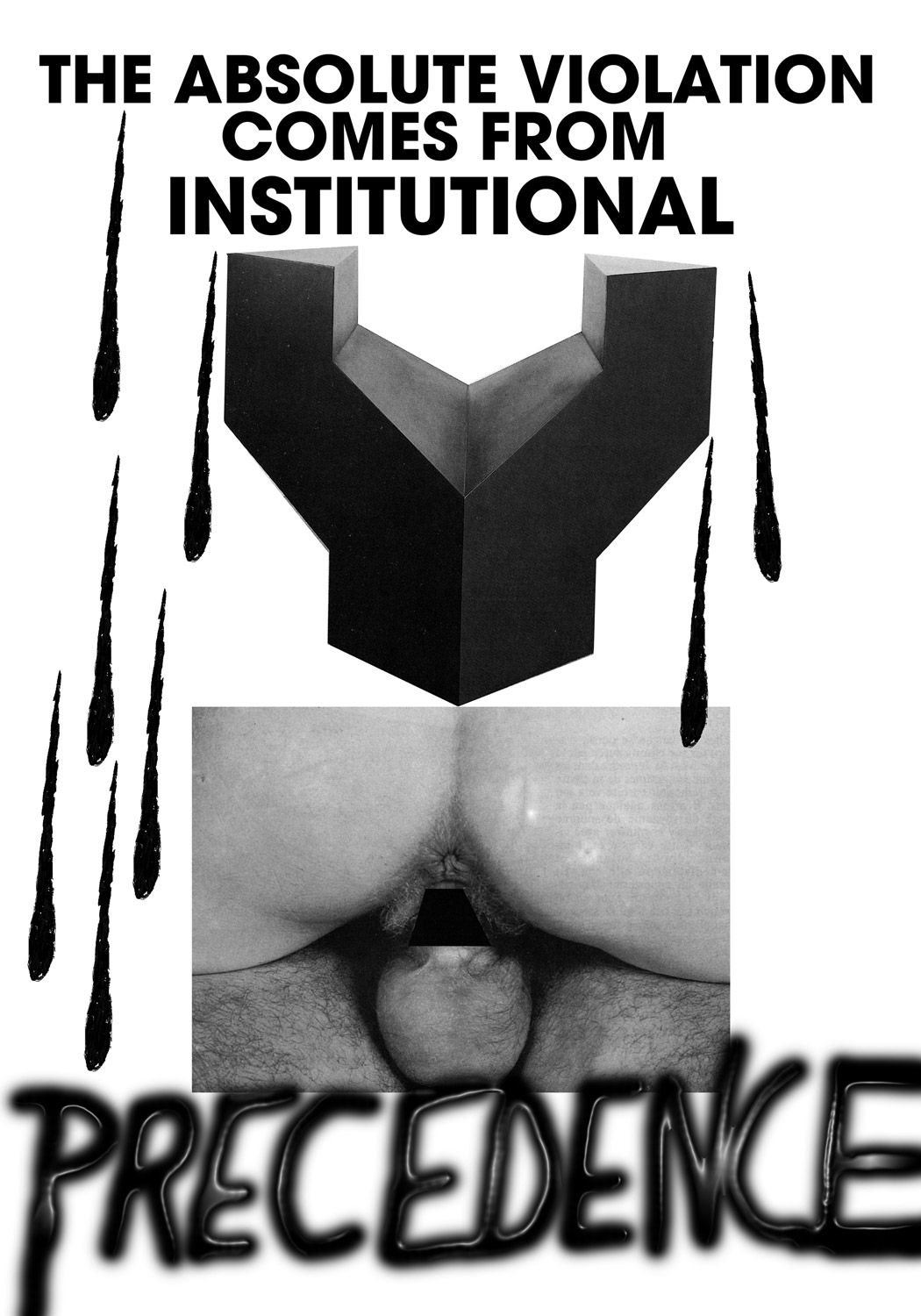

Absolutely—it was a bridge to all the gender-bending subject matter in this body of work. Nail polish was a way to incorporate that into my work, not only aesthetically, but also in terms of gender, authority, transgression, fashion, and economics. There are one-dollar bottles of nail polish, and there are forty-dollar bottles of nail polish; these materials don’t necessarily look different, yet they connote very different classes. The nail polish works were formally done. The ones I found less successful were the ones chopped up into grids, replicating the monoliths. Each piece had one image of a pre- or post-operative transgendered person. That was my way of incorporating all of these different things, things that cannot be watered down or made matter of fact or defined. Cultural phenomena, gender phenomena, and art historical phenomena I saw existing in one fluid line. But it’s not something that can be proven, it’s not something that can be defined—it’s an illicit merger.

Eliding minimalism with the architectural vernacular of incarceration, Ruby enters a “transversal” space of overlapping political and phenomenological realities. In his response to the American legacy of Minimalism, Ruby is overtly critical. His work attests that its approach was propagandistic, and that its forms were repressive. There are no value judgments per se, even though on occasion text appears in his work that co-opts a fiery rhetoric: “THE ABSOLUTE VIOLATION COMES FROM ITS INSTITUTIONAL PRECEDENCE,” “FINISH ARCHITECTURE KILL MINIMALISM LONG LIVE THE AMORPHOUS LAW,” and other raging cries of realpolitik abound in his word.

In Ruby’s purview it seems that abstraction is nothing more than the natural force of chaos, and that nothing is as perverse as the minimalist aim to silence and sharpen natural materials into artificial forms. Works with vindictive titles such as Absolute Contempt for Total Serenity (Falling Water) (2007) seem to mock-critique the sublimity of architectural modernism, namely Frank Lloyd Wright’s iconic residential design for Falling Water (1935) in rural Pennsylvania, by stacking up architectonic forms with mottled, spray-painted surfaces. Such exercises in construction are pushed to the extreme in larger work such as GRID RIPPER (2008) in which literal, minimalist restraint—a pile of colored monoliths—is exploited towards more expressionistic ends.

III. What type of architecture or urban environment do you like the most?

I follow it and have been extremely influenced by recent architecture such as Koolhaas’s CCTV buildings and the events that followed their completion. Architecture is hard because it’s such a catchall. When I went to school everyone was at least somehow influenced by architecture.

Was that the spectre of minimalism?

No, it was another lineage. It was basic architectural knowledge of form, things about spatial relationships, the way that things are built, and the way that scale operates on a human level. Those things are important to me, of course, but I never got into “architecture” per-se. But my work is informed by institutional architecture, penitentiary architecture, squatter architecture; I like architecture that contains within it a transversality.

Speaking of your forays into architecture, how did the Raf Simons project in Tokyo begin? Would you design another physical space?

Yes, I absolutely would. Raf and I are friends. When he was about to open up his flagship store he had the idea to give an artist free reign. When he asked me I thought, “What does free reign mean?” This was around 2004 or 2005, I had been bleaching fabric for some of my fiber work. What I wound up doing was photographing about nine hundred yards of this bleached material. The fixtures for the store were made from some of the actual bleached fabric, and represent positive objects. The photographs of the fabric were inverted into the negative and became wallpaper, which was then used as a kind of background for the objects—a mix of negative and positive.

And it went on the wall, the furniture?

Everything. The ceiling, the boxes, the fixtures, the glass containers were all incased with this bleached denim, or its negative image. It had a very disoriented feel. There’s no delineation between the walls and the floors, it’s very much an overarching, cyclical space. Structural elements were reworked. We built new walls, a new staircase. But I wasn’t really thinking about it as art. It was a good exercise in changing the infrastructure of a space that people are going to inhabit—and also, thinking about it as a box that Raf was going to put his merchandise in. You could put together this store and it looks great with nothing in it, but something goes into it, all the fixtures, all the clothes, everything.

It has to serve a function.

Exactly—so it’s not like art in that respect. I was thinking about Raf’s work and thought that it made sense because we are both interested in this demarcation of fabric, of surface. He is interested in the way people wear it and I am interested in the way that it creates a space. I am not interested in ever becoming a fashion designer, but I am interested in Raf’s sensibility. It makes a lot of sense for me to treat material and make something out of it. It was, in the end, a collaboration.

How was the Japanese response?

They loved it.

Years ago I remember thinking: here’s Sterling situated in Los Angeles, a city that has one of the most bizarre urban infrastructures of any place in the world, and how interesting it was that you were really thinking and looking at that. I just watched The Soloist, the film based on a true story about a homeless violinist who plays underneath a highway overpass and who loves the beauty of that incredibly brutal space. You’re in the center of Los Angeles, with all of its chaos and where one can revel in such a strange beauty, the bleakness of contemporary urbanity.

Los Angeles and San Francisco are key cities in the problem of the homeless. These types of cities, perhaps due to their warmer climates, have become sites for entire and separate transversal communities. To me this transversal scenario means that those spaces not only take on the personalities of the people living there, but the inhabitants take on the personality of the space.

Then there’s a flip side, I think, in cities like Berlin, where you have a sense of a city that has been rebuilt relatively quickly. You have these massive, concrete super-block structures of the former GDR. You see places that really haven’t left any gaps for what you are calling “transversal spaces.” You don’t warm up to that environment, and you could hardly plant a tree.

Berlin has a history of “ruin value”. This idea that you are talking about also has to do with Albert Speer’s architecture from the Third Reich. Speer’s initial planning phase revolved around “ruin value,” the idea that his structures would appear immediately as an archeological marker of their society. It is like trying to give history or significance to something with no history. Some of those buildings do still exist and are juxtaposed with new ones. That combination, again, an illicit merger, does come off as something that is perhaps transversal.

Are you originally from LA?

No I am not, I have been in LA for almost nine years now. I was born in Germany. We lived in the Netherlands for a bit and then moved to Baltimore, Maryland, where I grew up until age eight. This is where the American side of my family is from. Early on I was exposed to the inner-city Baltimore school system, and then its exact opposite, a rural, mostly agricultural school when we moved to Pennsylvania, which is where I lived until age 18.

There is an essay on violence in Walter Benjamin’s classic anthology Reflections. He claims that the destructive character is one that likes open spaces. It’s interesting, because when you think of somebody destroying things, you think of someone being in an environment that is enclosed. Of course, Benjamin is writing in the context of war, and so you have this sense that to truly destroy something is to annihilate it and leave nothing behind. Do you see a destructive element to your work? Is it ever defacing or effacing?

Yes, absolutely, but again, I think it encompasses and translates those destructive elements in a positive way.

When you’re adding elements though, do you ever say, well, this is a positive element or a negative element? This is something that gives it a little bit more anger, or a little bit more darkness?

Sure, there are elements that do that. There are also things that seem completely spatial or dark, which are more abstract. That is a positive to me, when it gets lost and becomes abstract—as if in reference to eternity or space.

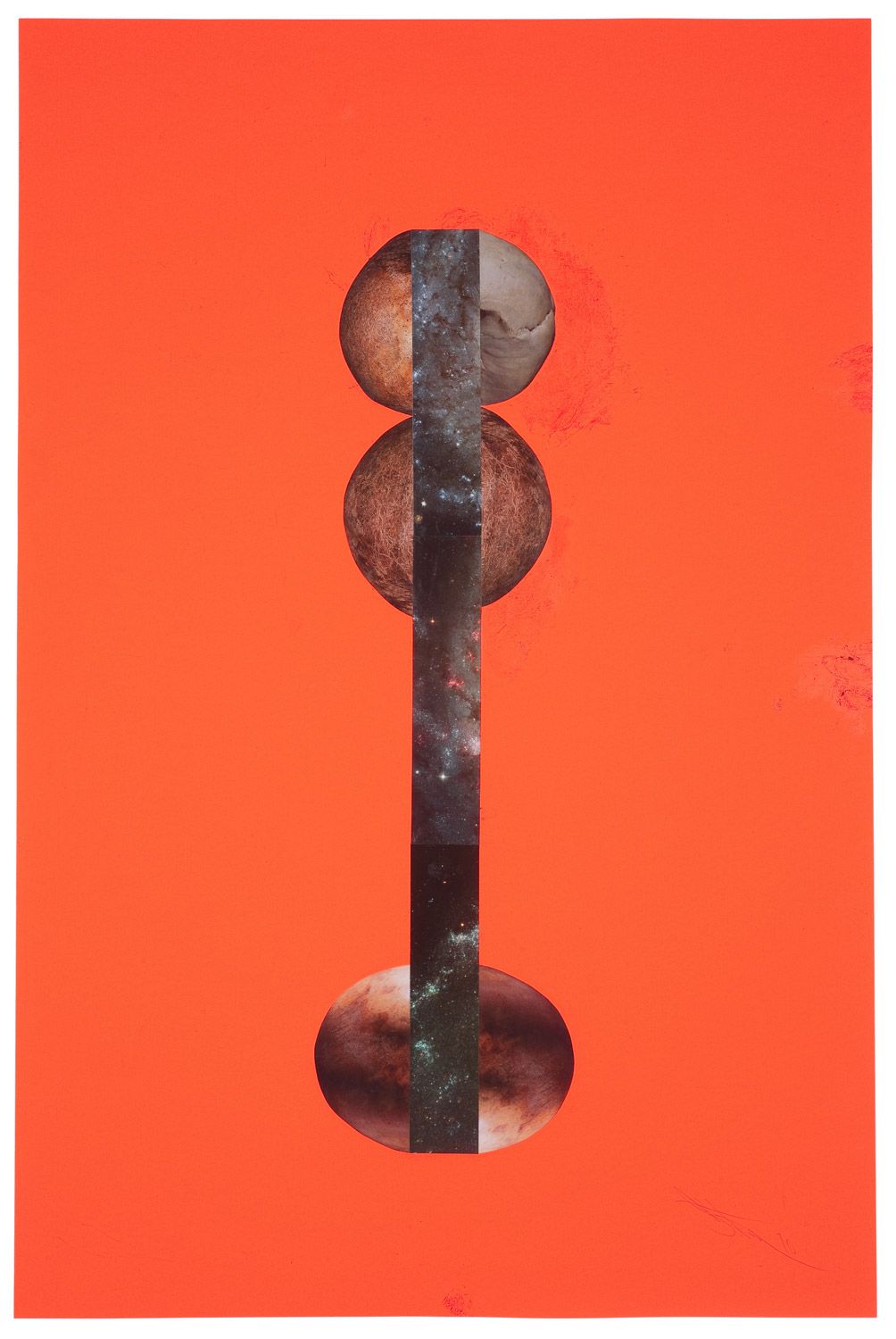

Ruby’s vocabulary is constantly mutating and expressing danger, as in the animal kingdom where the evolutionary expression of bright colors distinguish a poisonous creature. Similarly, in a manmade environment fluorescent colors are used to warn or avert, to caution or police, to highlight or even to castigate, as with the choice of a fluorescent orange uniform for a prisoner. Color is sometimes easy to overlook, yet considering his formal choices ruby proves to be a well-versed student of that artistic tradition. Tony Smith is often referenced in connection with the herculean stasis of Ruby’s work, but what about the influence of Barnett Newman’s sculpture such as Broken Obelisk (1963–69) or his less wellknown painted, sculptural totems? What about the spatial plasticity of Lucio Fontana’s little-discussed polychrome ceramics, and the direct resemblance that they bear as predecessors to Ruby’s own?

For all his radicality, his use of grand, historical abstraction is cocksure, some times even conservative. When he does present a relatively intact piece with clean lines, inevitably less baroquely abstract, their ambitious scale inputs their own ruin value. The spectre of violence seems to be sublimated under each surface, seething with the hope of destruction. The concrete Wall, the iconic surface that was defaced and denounced by countless citizens, is precisely the sort of reality Ruby’s work mirrors as his con. Yet the concrete slab structure of the Wall, in a twist of ironic fate, would have been abhorrent to someone like Speer and his plans for the new antiquity of Berlin. In a chapter on Speer in the classic study Bunker Archaeology (1975), Paul Virilio traces the concept of “law of ruins.” Of Speer, he writes:

“In 1938, this conservative conceptualized his lack of imagination in a ‘theory of the value of ruins.’ According to Speer, ‘the structures built with modern techniques’ would not be appropriate to bequest to future generations, ‘this bridge of tradition’ demanded by Hitler. It was unthinkable that this pile of rusted rubble could one day inspire heroic thoughts, just as monuments of the past were able to do. My theory was designed to solve this dilemma. I wanted to give up using the modern materials found in metallic and concrete constructions. By respecting certain laws of statics, buildings could be constructed that, after thousands of years, would closely resemble Roman models. The monuments designed according to this ‘law of ruins’ were inspired by Caracalla’s public baths, the altar at Pergamon, Athen’s stadium, the domes of Étienne-Louis Boullée, etc. and this shoddy bazaar would survive in the cadaveric rigidity of elements.”1

What’s not to like in decay, such as the type that fills the terrain of ancient Rome? I have often walked the streets of Washington DC and wondered what its Greco-Roman facades would look like in an apocalyptic vision of the future. Walter Benjamin once said, “Allegories are, in the realm of thoughts, what ruins are in the realm of things.”2

An attraction to such brooding scenarios is, after all, similar to the type of curiosity that has compelled audiences throughout civilization to sympathize with the devil, with the kind of interminable fasci nation that regards Ruby as bold contemporary artist, and Dante’s Inferno as an indispensable touchstone of thought produced in the last millennium.

As we concluded our conversation in the private viewing room of Pace Gallery, surrounded by examples of his work, I felt like an armchair nihilist surveying the ruins with glee. Although we had not spoken of another recent project, a film titled The Masturbators (2010)—yet another perplexing extension of his repertoire—I was inclined to file it away, at least for the meantime, as a brash act of late Warholian brilliance, since masturbation is in some sense itself an abstraction of bodily function. We had run the gamut of his industries, and I had entered his allegorical hell with the kind of relish that aesthetes and enthusiasts alike reserve for their pleasures.

1 Virilio, Paul. Bunker Archaeology. George Collins, trans. New York, 2009.

2 Benjamin, Walter. “Paris: The Capital of The Nineteenth Century” (1935) in Charles Baudelaire: A Lyric Poet In The Era Of High Capitalism. Harry Zohn, trans. London, 1997. p. 178.

Credits

- Interview: STEVEN PULIMOOD

- Photography: HEDI SLIMANE