Hysteric Americans: Berlin Review

|LUCY BROOME

In today's media landscape, a book review is often a slap on the back. A handshake among colleagues that says, "well done." But we have never been afraid to offer critique when critique is due. In our print section Berlin Reviews, we've always tried to take the propositions of a book seriously and push them to their extremes.

In an essay for Roe Ethridge’s American Polychronic, psychoanalyst Jamieson Webster writes, “Roe Ethridge is a hysteric. Even worse, he’s a male hysteric. Nail in the coffin, he’s an American male hysteric. I could add artist. But I won’t.” Why Webster would add “won’t” might be because he isn’t only an artist. Aftergraduating from the Atlanta College of Art in 1995, Ethridge moved to New York, where he began working as a commercial fashion photographer while also producing art photographs, placing himself at the intersection of the commercial fashion industry and seemingly less commercial art world.

American Polychronic documents both types of Ethridge’s output through interweaving his creative work with commercial jobs for the course of the book. Ethridge describes the book’s form as a fugue, a musical composition wherein a short melody is introduced by one part, then taken up and contrapuntally developed by other voices in a continuous weaving. Ethridge has an intelligent take on the fugue. He shows his creative work chronologically (from 1999 to 2022) and his commercial work in the opposite direction (from 2022 to 1999), weaving the two narratives together. Thus, Ethridge’s Hermès AW-2021 campaign is followed by his SS-2020 campaign for Telfar, and his artwork Ambulance Accident (2000) is followed by the photograph titled Weebleville (2005). The result at times is disjointing, which is where Ethridge leans into his musical analogy: “A sequence has to sing. It’s not just something to decode and find the true meaning of. I have to feel its harmonies and disharmonies.”

Arranging the photos in this way also creates a feeling of malleability. “Real” moments of rotting food are juxtaposed with “staged” moments of models shoveling noodles into their mouths. The real is injected with flatness and irony, with an exaggeratedly fake smile or out-of-place logo. There is an uncanny dimension to Ethridge’s work, which touches upon the other meaning of fugue. In psychiatry, a dissociative fugue is a temporary state in which a person has amnesia and ends up in an unexpected place. People with this condition can’t remember who they are or details about the past—something that could be said of the photographs themselves.

In Webster’s essay, she writes that photography has changed memory byfunctioning, in some ways, as a double to the storehouse of the mind. She asserts it is hardly possible to recall anything in the day and age of the personal archive—the personal archive being the matter we store on our phones. In the era of “photo dumps” and photographing our own “chanced-upon vignettes,” we tend to haphazardly reform and over-curate to portray a casualism, which is ironically the complete opposite of what initially was intrinsic to using social media (i.e., sharing “real moments”). Arranged in the fugue form, Ethridge’s book seems to lean into this collective cultural notion of time and memory that is in a fugue state and nonlinear. By doing so, each work lives in its individual nonpareil moment despite being placed in some complex harmony with the next.

Through American Polychronic’s punctuation via brands and logos, with celebritiespopping up, whether Grimes or Willem Dafoe, the book is unequivocally American and, through its melodic disruption of time, also polychronic.

Credits

- Text: LUCY BROOME

Related Content

Cornered: Berlin Review

An Internet the Size of a Room: Berlin Review

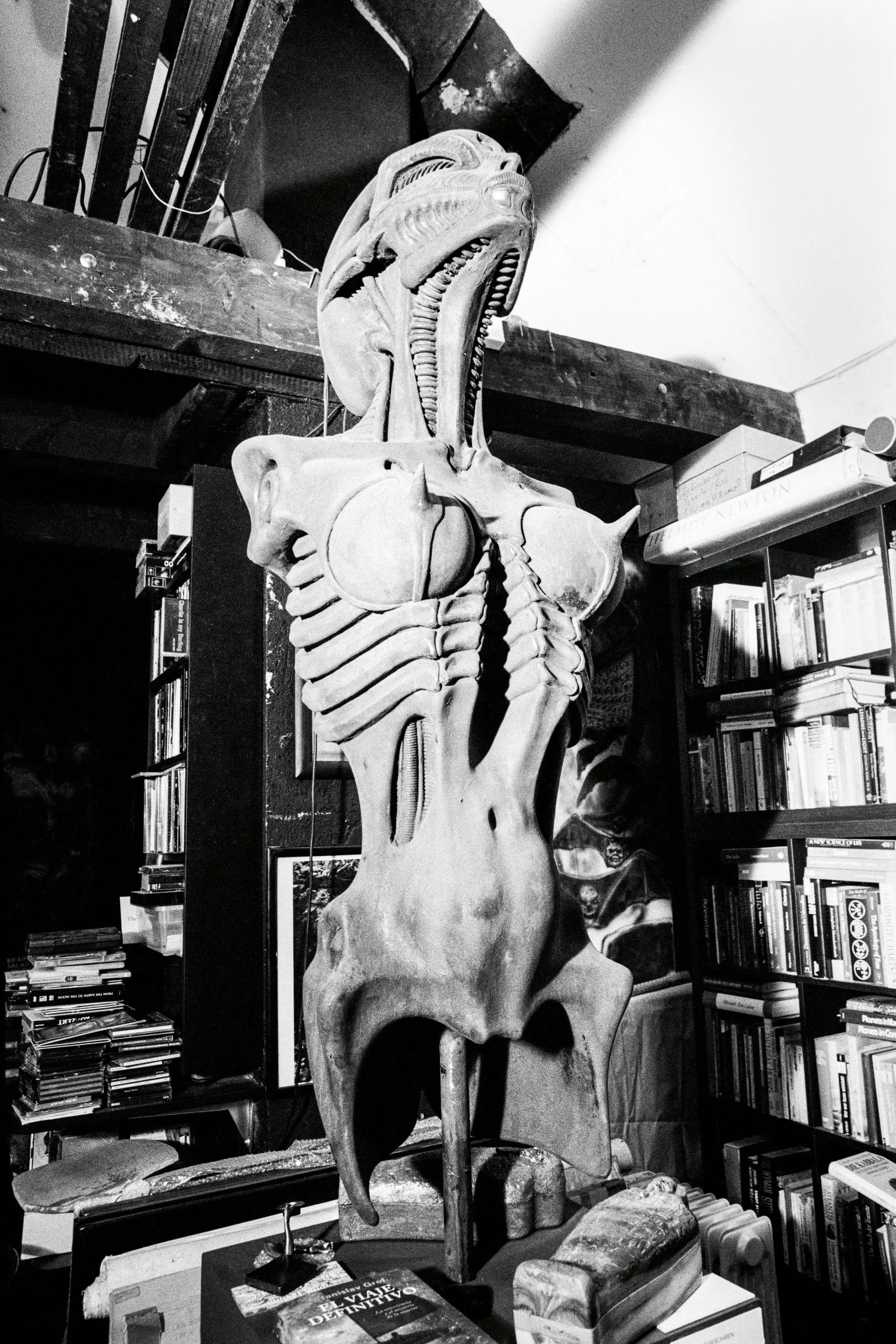

Libidinal Teratology: HR GIGER by CAMILLE VIVIER

The Art of Collecting Chairs

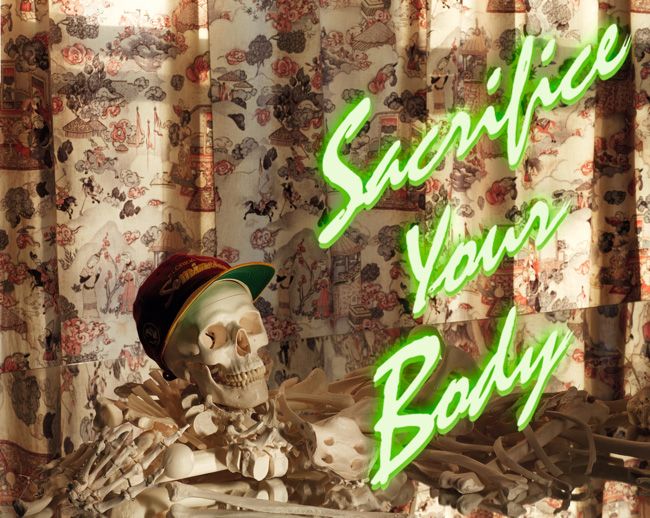

SACRIFICE YOUR BODY: Photographer ROE ETHRIDGE Tells Us About His New Exhibition and Making Accidentally Great Pictures

Sculpting in Time: WILLEM DAFOE on Being “Inside”

032c Issue #43 “CULTURE CRISIS. Therapies for the confused” Summer 2023

“Gudbay, America” – Behind-the-Scenes with Designer GOSHA RUBCHINSKIY