RICHARDSON Magazine Rethinks The Seedy

|Bethany Wright

Launched in 1998, Richardson magazine seeks to dig out the snubbed world of porn and elevate it to the surface of mainstream media by compounding it with highbrow figures of the fashion and art world.

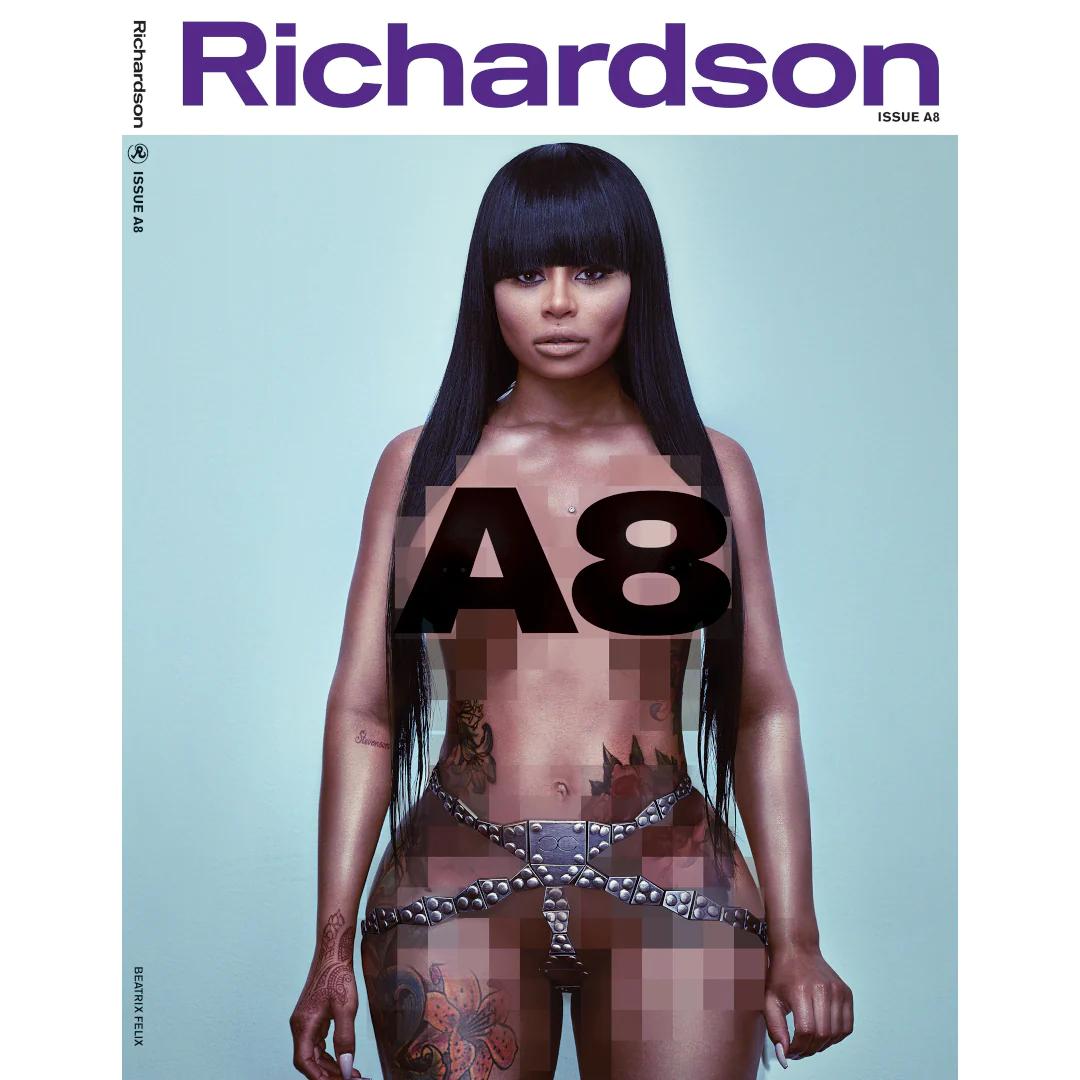

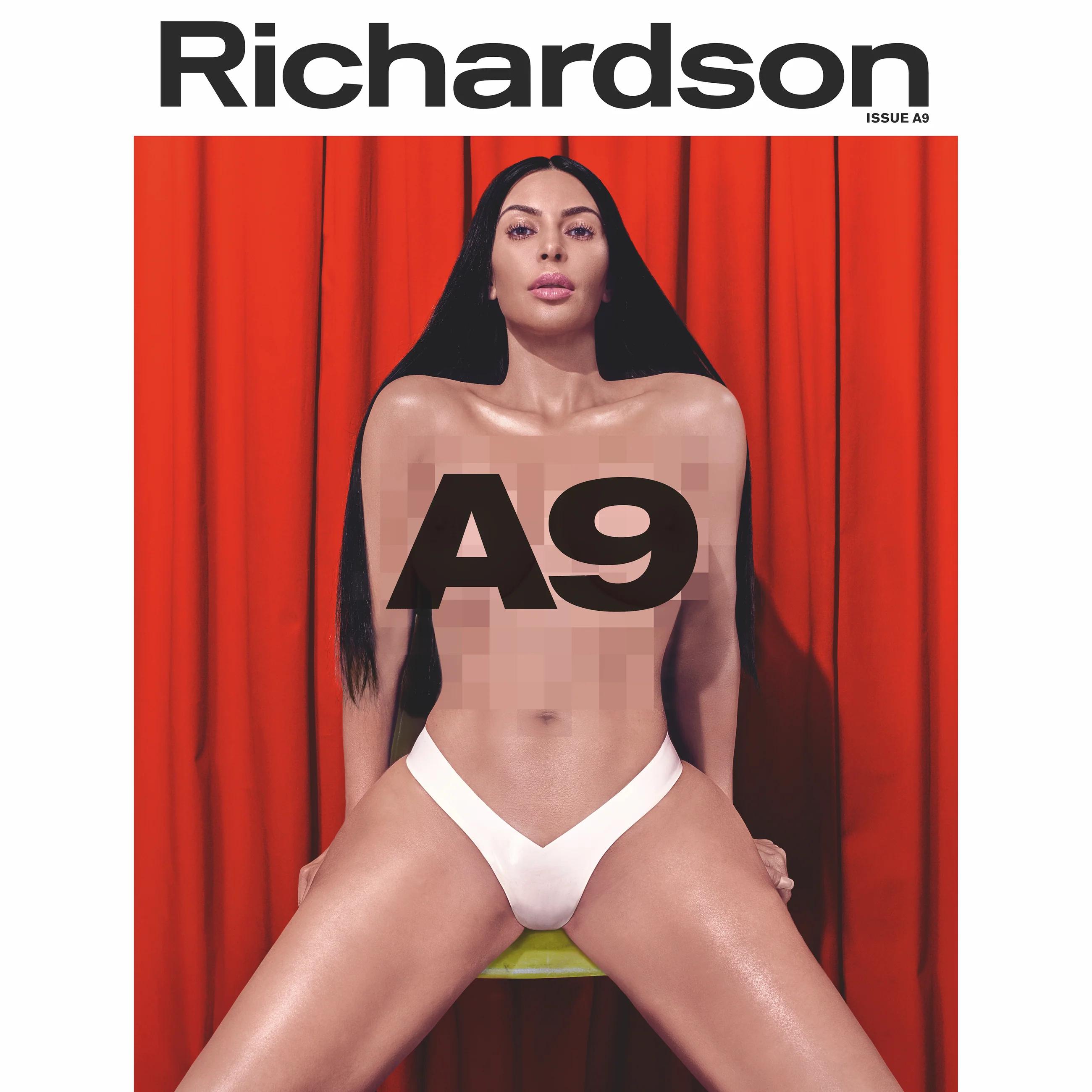

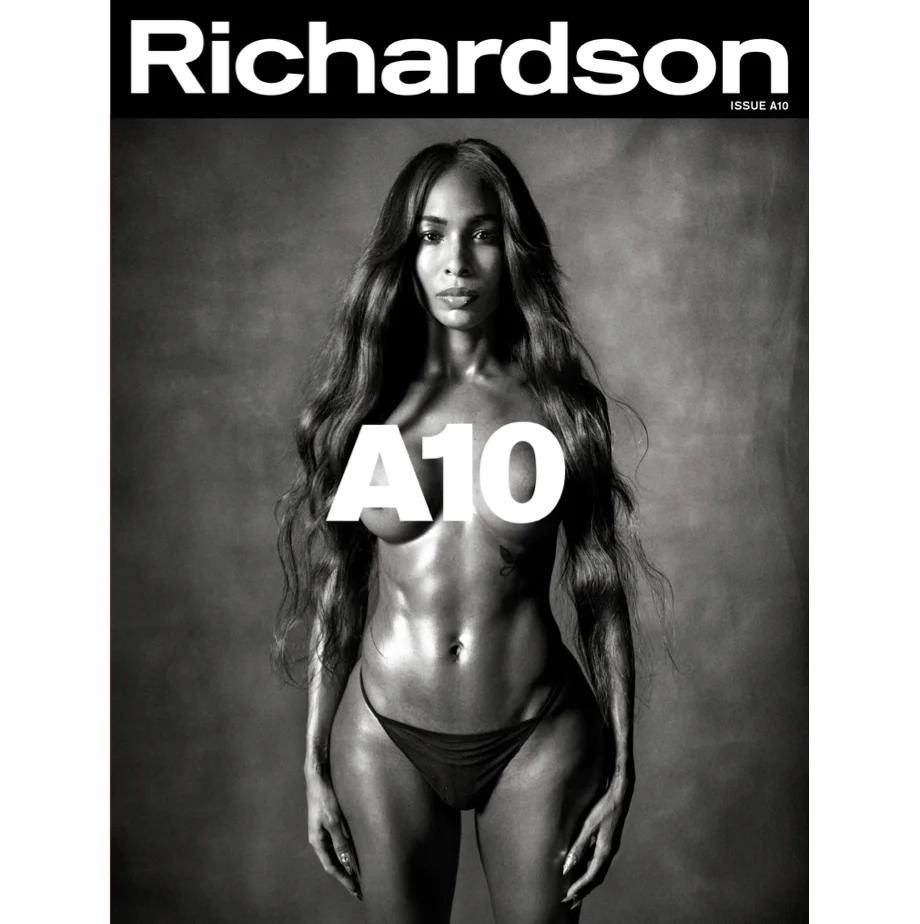

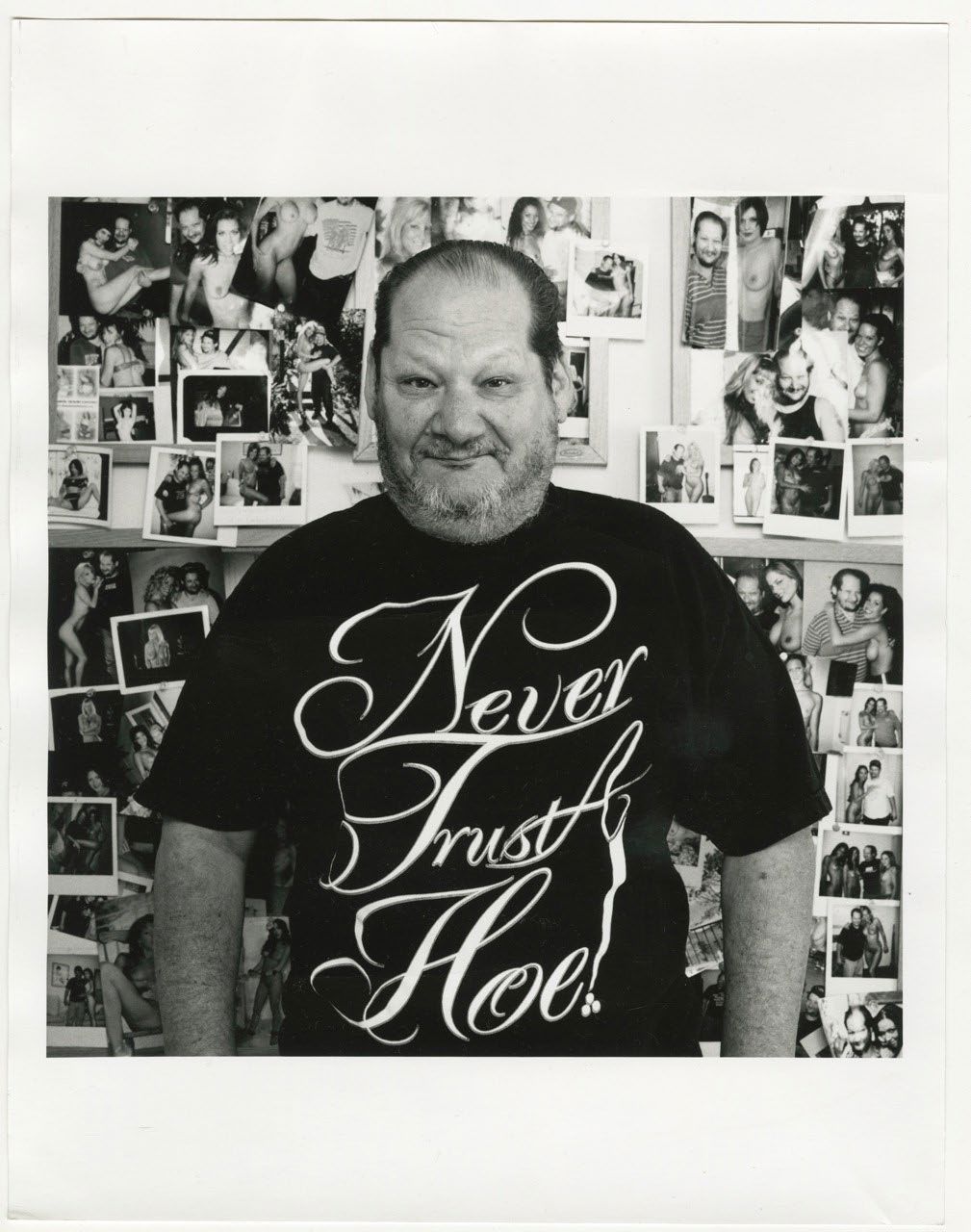

Richardson has published 11 issues over 26 years, past cover stars include Kim Kardashian, Blac Chyna, and Tori Black. And the magazine has featured work from the likes of Jack Donoghue, Tracey Emin, Lucien Freud, Juliana Huxtable, Martin Parr, and Jenny Saville, among others.

For Issue A11, The Agency Issue, founder Andrew Richardson and editor Esra Soraya Padgett have focused on Japanese pornography. The “brief survey” includes a 40-page Rosie Marks shoot documenting one corner of the Japanese BDSM scene and a conversation with adult video director Toru Muranishi and performer Hazuki Wakamiya, in which Richardson uncovers the uniqueness of the Japanese industry and its differences to the Western market with regards to consent, aesthetics, and legality.

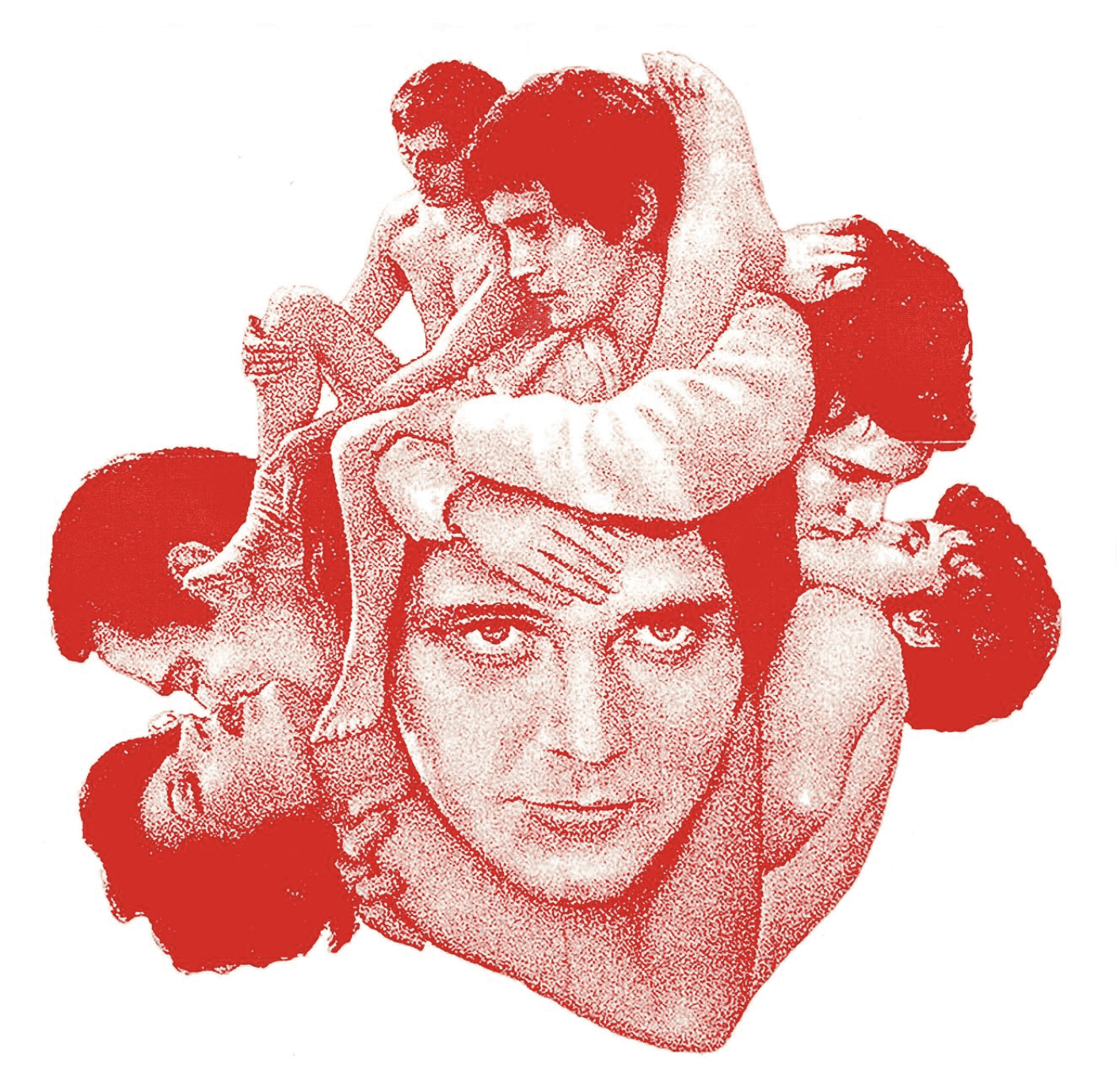

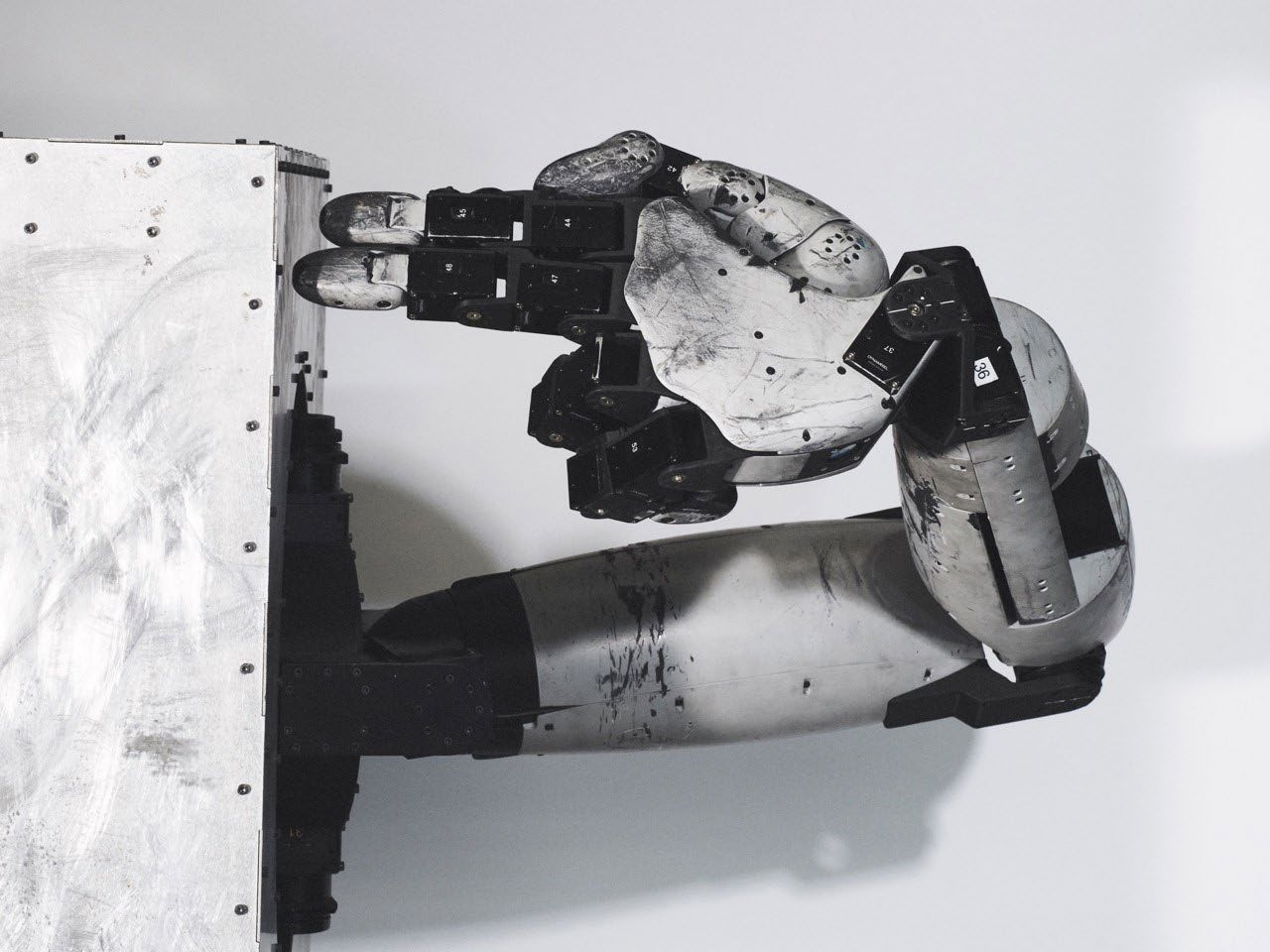

A11 also includes essays by Avgi Saketopoulou, Anna Khachiyan, and Bruce LaBruce—exploring, respectively, non-consent as a tool to understand internal “otherness,” post-feminism’s lack of consciousness, and Pasolini’s Teorema—an account of Julia Fox’s initial experiences as a submissive, and artworks by Hajime Sorayama and Jordan Wolfson. This and a cover of Rae Lil Black, shot by David Sims, posed in a Saint Sebastian like stance, followed inside by a conversation exploring her past dreams of being a politician and her manipulation of the algorithm, demonstrate that Richardson is a vehicle to challenge mainstream’s notions of liberalism while bringing readers beyond the chambers of their familiar experiences.

Here, Bethany Wright speaks to Andrew Richardson and Esra Soraya Padgett about the psychological dynamics of sex, standards of compliance, and marketed sexual exposure.

BETHANY WRIGHT: You have been working with Pornhub since issue A9. How do they facilitate the making of Richardson magazine?

ANDREW RICHARDSON: As you can imagine, I found it very difficult to get advertising or support for the magazine over the last 26 years. We rely on anti-establishment companies for investment. Hysteric Glamour, Supreme, and Pornhub are the only businesses that have given us money in the history of the magazine. As the emphasis of an issue is usually heavily weighted on the cover, it is great to be supported by Pornhub as it enables us to do bigger shoots. They are easy to work with, and they support a lot of interesting people and projects. They also have definite ethical and compliance boundaries that you have to respect—but you would want to respect those anyway.

BW: How would you define that Pornhub and Richardson boundary?

AR: There are a lot of things we wouldn’t do. But when you are working with a company such as Pornhub, you must be particularly mindful of these compliance standards.

ESRA SORAYA PADGETT: There are a number of things that, in the context of porn, are unacceptable but in other worlds, like cinema and fashion, you wouldn‘t blink an eye at. The presence of guns, for example. If everyone is aware of the fictional context, their representation is permitted in most cultural settings. However, within porn, those same images need to be avoided altogether.

AR: However, everything doesn’t stop at the point of compliance—there is a whole world one wants to explore. Consider Japan and America, there are huge differences in standards of consent between the two. We’re stuck with Western boundaries on the psychological aspects of sexuality, where imagination and reality are cut off. But within Japanese manga, games, erotic game play, and pornography, there is a psychological dynamic based around shame and embarrassment. If you ignore these wider contexts, you deny yourself an understanding of your own psychology.

BW: You summarize your findings regarding the differences between American and Japanese pornographic aesthetics in the statement, “America is the sun and Japan is the moon.” Is this in reference to their psychology?

AR: That relates to the way in which Japanese and American pornography are made. American pornography is extremely visual. You see the penetration—the real or imagined orgasmic, ecstatic, reaction. It is physical. It is “positive.” In contrast, Japanese pornography is far more psychological. It is dark in the same way moonlight is. There is more darkness in the fantastical imagination.

Freud described sex as being a power dynamic, but really, it is a power exchange. The idea that sex is really about power can be difficult for a lot of people, especially considered in a Judeo-Christian orientation. People are not always interested in getting into an insightful debate or exploration of the human psyche, so sex is put into cookie cutter digestible morsels.

BW: Sex work is becoming more normative as the overlap in porn and pop culture increases, especially within “personality” careers. Your past cover star Blac Chyna began her career as a stripper in Atlanta but now she’s defined as a “TV personality and model.” Mia Khalifa had a short stint as an adult actress, and Julia Fox had her start as a dominatrix in a New York dungeon in 2008. Mainstream culture has become increasingly more accepting of start-up sex careers that evolve into something else. What do you think of this?

AR: That’s been going on forever. Every epoch seems to have its own historical prostitute or sex worker who becomes famous for flouting society’s standards of what a woman should or shouldn’t be. Kim Kardashian, who we had on the cover for A9, is probably the most famous woman in the world but that star moment came from her sex tape when she was Paris Hilton’s stylist. Julia Fox is another example, I have known her for ten years now—she is a great force of nature and extremely driven. These women do not become famous solely because of a transgressive or sex positive action. It may be the initial source of their notoriety but afterwards they put in an enormous amount of hard work to maintain it, as with anything conducive to fame, be it status or income.

BW: So, in a sense, sexual exposure has become one of the footholds in the pursuit of the modern American Dream?

ESP: Rae Lil Black, A11’s cover star fits this description. We only knew her as an adult star until, during the interview, she said, “I am barely in porn anymore, I am a Twitch person and a food blogger.” She translated it into being a powerful influencer. People can, without blinking an eye, say, “I got here from having 12 million views on Pornhub, and now I am a blogger.”

AR: When you consider the type of person who watches a lot of porn, they are often gaming, living in acute, online, and somewhat isolated environments. They occupy a whole digital world which enables pornstars to expand outside of the adult space and migrate into the mainstream. Rae [Lil Black] understood the algorithm, she learnt how certain angles of her body and face performed better online. The girls who are successful in the porn industry today are incredibly good at marketing. They don’t need an agent. They know exactly how to generate memes of themselves, create viral moments, and tap into toxic male panel discussions, or whatever it is.

It is such a different world now than when it was in the early stages of the magazine. Compare Jenna Jameson, a classic pornstar, who had a contract, did two or three movies a year, a couple of signings, and a few in-person things. These girls have got whole teams that do media for them. It’s the same as any celebrity but it’s far more interesting because they operate outside of the “legacy” media constructs and in the complete chaos of the internet—but they understand it so well. They know how to manipulate it to the point that they can fabricate moments, authentic and inauthentic, that further their career.

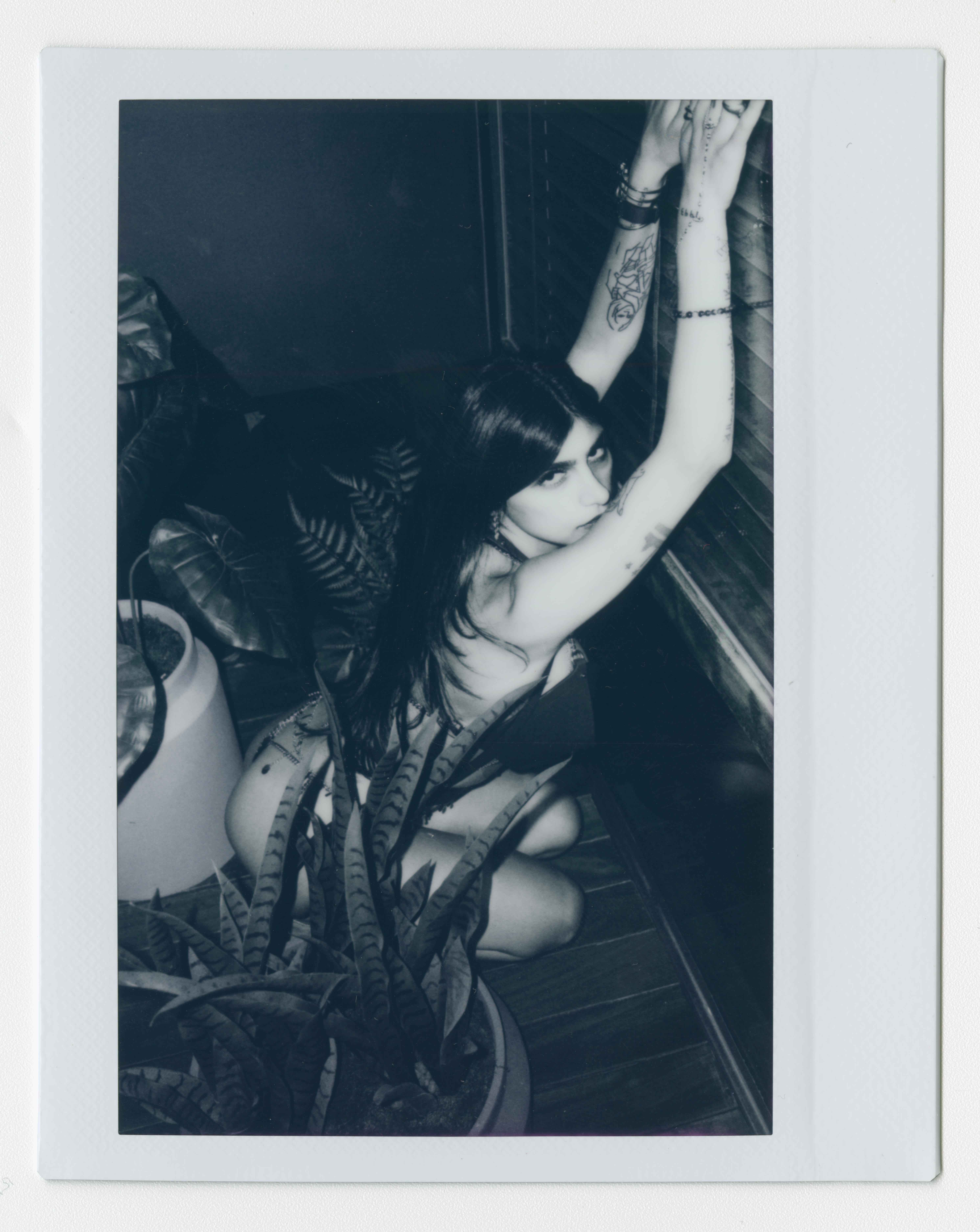

BW: When I look at the way you have chosen to capture the women on your covers, I am reminded of a story about the late Carlo Mollino. After he died, over 700 polaroids depicting women in various erotic stances were found in one of his villas. The photographs were originally thought to be candid but on closer inspection, you could see that the women had been posed. One of the consistencies throughout was that their hands were flipped at the wrist. In the majority of your covers, the model stands, naked, directly opposite the camera, with the issue number written and placed over their breasts. Could you explain this decision?

AR: When I first started the magazine, it was at a time when I only knew who Jenna Jameson was because I had listened to Howard Stern. It was before the internet, when pornography was not readily available outside of peep shows and sex shops. I had this idea—taken from Stern, in a way, and how he interviewed pornstars. I wanted to do a different type of interview and shoot them with well-known fashion photographers as a means to elevate the whole thing. The way the cover is cropped, mid-thigh. The woman caught is in a stare down moment. Squared-up and straight forward. The idea was to confront mainstream prudishness. So, fundamentally, it is about confrontation.

BW: Body politics are localized. If you think about European countries such as Italy and Spain, it has been normalized for women to sunbathe topless, but this is not the case in England. Germany provides a great example too; historically, East Germans were known to be comfortable with nudity whereas West Germans tended to be more conservative.

In today’s culture, we are quite confined in echo chambers of our own opinions, either through place, people, or both. How would you describe your own body and sexual politics?

AR: In different parts of the world and within varying religions and legal structures, the boundaries all change. America is such a big country but there is a bottom line of puritanical weirdness where there’s hysteria if you have a four-year-old child running around a beach naked. As much as you think about sexual openness—with the Only Fans culture or marketed sexual availability which has been going on since the advent of television—it is offset by a fear of nudity and an institutional terror of sex in American culture.

For me, sexuality is the ability to lose your self-consciousness and become a human animal. You want to have that primitiveness in your canon of things you are comfortable being. Part of organized religion’s job is to suppress that part of your human self; to make you afraid of it, and transform you into a conformed, obedient member of a social infrastructure.

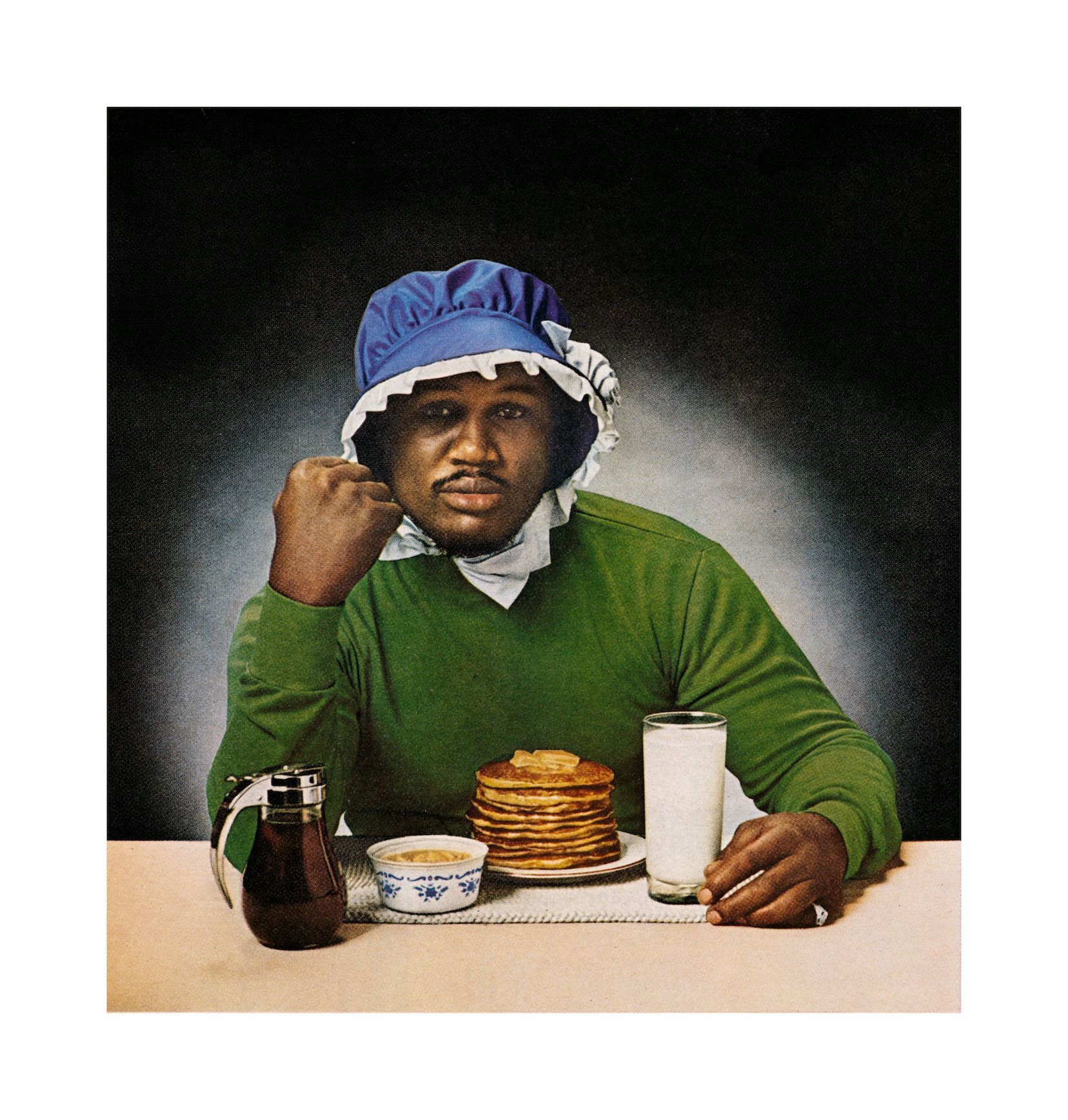

ESP: The purpose of Richardson is to call echo chambers into question and to see outside of them. Within the study of the Japanese adult industry in this issue, there is a portion about mosaic, which is a method of censorship used where a group of pixels covers the genitals. This allows for plausible deniability over whether or not penetration happened as the making and producing of porn is illegal in Japan. What was eye opening for me was that, because mosaics have been in place for decades, there is an eroticism about that censorship. We come from a place, and in America especially, where censorship is the enemy, all the time. But they think, “I thought what got guys off is the ability to not see everything,” and have built a completely different framework of eroticism around that. That was the echo chamber moment for me, finding that it is not about beating down the door of censorship all the time. Eroticism comes from the taboos and prohibitions we have, and that changes when you go somewhere else.

BW: In the Richardson archive, there is a heavy emphasis on women as content. While you’ve also featured creative work by women, most of the covers have been shot by men. This issue has a larger majority of female voices. What informed this shift?

AR: I can and do look for a type of person who has a certain point of view which suits my own agenda, and whether they’re a man or a woman is neither here nor there. There are a lot of people who create erotic art who do not fit the point of view we have and are trying to communicate. The area of content making we are operating in is quite specific. We don’t have a large pool of people to choose from and we also use the same people—Bruce LaBruce, for example, has been doing stuff for the magazine since the very beginning. There was never a deliberate inclusion or exclusion of anybody.

BW: But the fact that there is this imbalance does make a statement about gaze, whether that is intentional or not.

AR: In A4 we featured work by a 60s photographer called Gunter Rambo created some work for us, and he had this perfect female gaze. There are a lot of men who have more of a female gaze, and there are many layers to unpack in a conversation around the female gaze in the male gaze.

ESP: This issue is so heavily female, which speaks to the theme; but in terms of who we thought of and who we wanted to talk to, it was not a move to be intentionally inclusive.

AR: It is really simple. I met Rosie Marks because somebody I knew had said to her that she would be interested in my projects, and she came to meet me. We worked around her schedule, and she worked around ours. In A11, she has a 50-page feature, which we have never given to any single photographer. But she was the right photographer for the job. We are not so rich that we can do whatever we like, we are pulling rabbits out of hats all the time. Our pursuit to gain access to the Tokyo BDSM scene was incredibly difficult, it took ten years.

BW: How did you get access?

AR: I was interested in doing these photographs because a friend of mine, who’s a well-known English female painter, had been in Tokyo around 20 years ago and had done a bunch of reference photographs in S&M clubs. I had an imagined idea of these clubs. It was from there that I then went about trying to find a way to get into this world. I nearly had access right before the pandemic. There was a big scene in Kyoto that we were beginning to get into. One night, Hajime Sorayama took us to a BDSM themed night at a Ginza bar. In Japan, the brand and magazine are quite popular, so people recognized me and introduced us to others. We met a famous dominatrix who put a tweet out to see if anybody would want to be photographed for the issue. We rolled up to do that shoot, not knowing what to expect—whether it was going to be a fashion BDSM situation. It turned out to be incredibly hardcore. We were all quite shocked but Rosie [Marks] soldiered on and captured amazing photographs. It was a lot of luck. As with everything with the magazine. You persevere.

BW: You once described Richardson as an anti-establishment Details, the Condé Nast men’s magazine from the 90s. Details can be used as a case study to understand the new wave of masculinity surfacing during the late 90s/early 2000s where male interest in beauty and fashion was becoming both popularized and normalized. What would be the findings of Richardson as a cultural artifact?

AR: For me, it’s like a bad habit and it is very difficult to see the magazine in a cultural context because I’m a bit too close to it. The excitement and the “victory” are just doing it. We are probably the longest running, least financially successful publication in the history of magazines. This magazine just exists, and it is a reflection of the time it is made in.

ESP: It still is an anti-establishment detail that operates in a constantly shifting terrain of subculture where you have to renew efforts to find what the fringes are.

AR: In this issue, David Sims photographed the cover and the Jordan Wolfson sculpture. The thing that makes most people, like Jordan or David, good is this anti-establishment feeling. David and I grew up in a post-punk, new romantic, new wave, Joy Division era in the UK when being the antihero was the goal. The artists I tend to like have a lot of antagonism in their work where they reflect, spotlight, or confront conformism. I am not interested in toeing the line or normality. I have always been drawn to provocation and we give opportunities to people to present their existing provocative work or create new work of this nature with us.

BW: Where do you see the future of Richardson heading?

AR: When I was a kid, a friend of mine’s father was the editor-in-chief of the Corriere della Sera, a big Italian newspaper. I saw these comics called Frigidaire. It was an Italian magazine, born out of the left-wing, 70s ethos of Italy. It was anarchist, socialist, Pasolini-esque. The magazine had pictures of La Cicciolina, a famous porn star, on the cover. Mafia slayings. A cartoon character called Rank Xerox, who was a humanoid, psychopathic killer made from parts of a Xerox machine that I’m sure was the inspiration for Terminator. It had fucked up National Geographic stuff about cannibals. That half an hour in which I saw those magazines was the most inspiring moment of my life and I cannot even read Italian. When I got the opportunity to do a magazine, I knew I wanted it to be like that.

The future of the magazine is to just do another one. Find somebody to give us money, find someone to give us access. For me, there is anxiety about communicating at a surface level and not being able to achieve the deepest access in order to uncover something profound, either because you don’t have it in you, or they don’t see it in you. Out of everything under the Richardson umbrella, the magazine is the most important thing. I have realized as I’m getting older that I am most interested in the access the magazine gives me.

BW: I understand that. Owning something or having a job that provides you with insight into worlds you would be othered from is a real privilege.

AR: That has been the thing from the beginning. I was the stylist assistant on the Madonna Sex book but I did most of the work because the stylist I was working for was doing something else. I spent my time running around transgender sex shops, stores where drag queens bought their clothes, rubber fetish places, and gay leather traders. All these places in New York that had been there, out in the open but were places I had never been into because I had no reason to. It opened up a whole world for me which ultimately led me to doing the magazine.

You’re born into a pattern and if you’re lucky enough, then there’s a certain timing that you’re born into. It has all been the right place, right time. That, paired with weird access and continual curiosity.

Credits

- Text: Bethany Wright

Related Content

Culture of Critique: Prelude to WALLET Magazine’s Issue #9

“It’s Important to Be Visionary Rather Than Reactionary”: Artist Hank Willis Thomas’s Aesthetics of Mass Action

Editorial Roundtable: KAZEEM KUTEYI of New Currency

The Play-Doh Bunny: A History of Playboy

From Gutenberg to Juggs: Celebrating Print’s 567th Birthday with Sexy Book Editor DIAN HANSON

Brenda’s Business with MIA KHALIFA

CHET LO’s BDSM Sweaters

Sin City: 2023 Pornhub Awards