FKA TWIGS Returns to Planet Earth

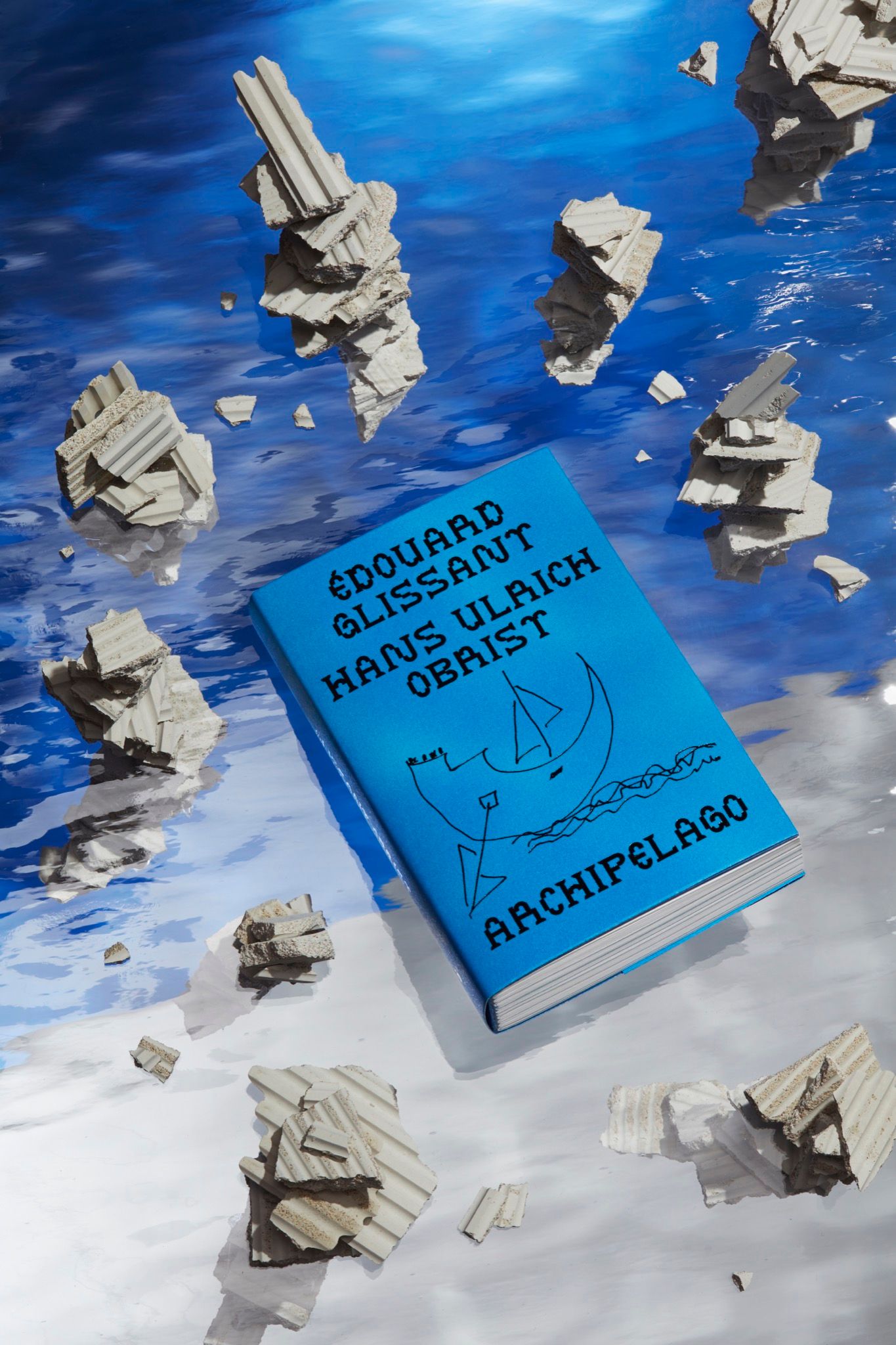

|Hans Ulrich Obrist

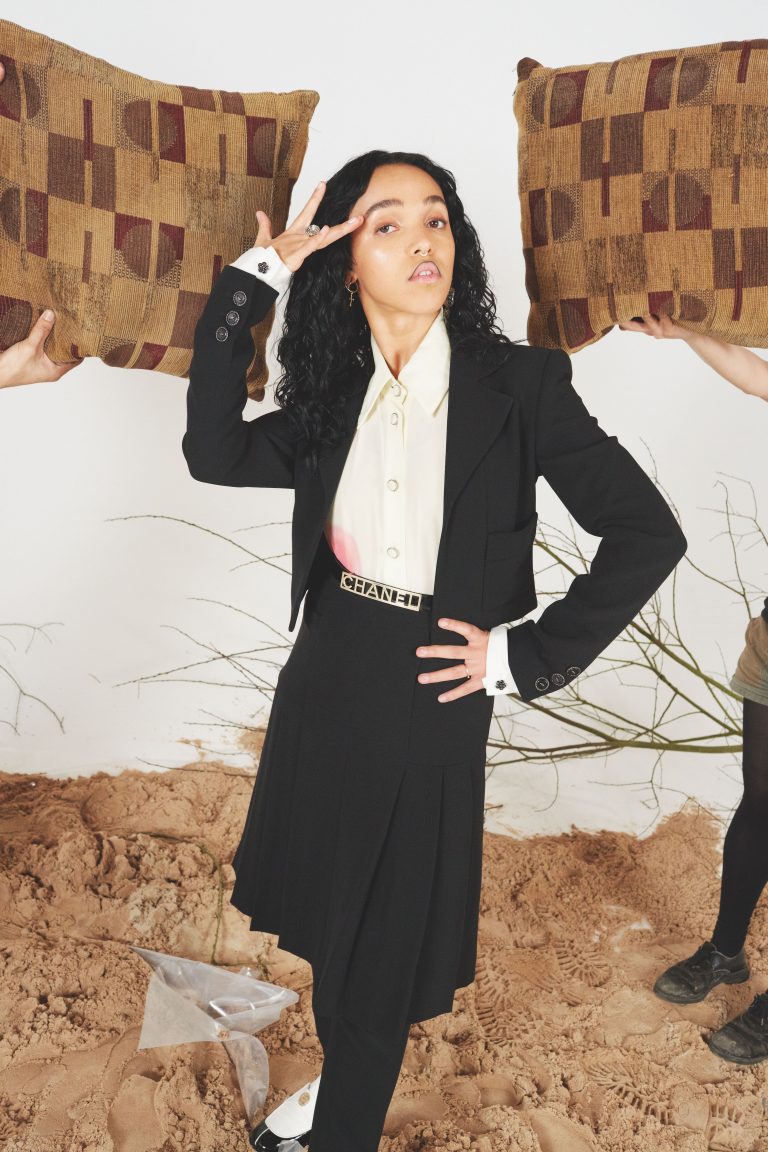

With her breakthrough album LP1, FKA twigs re-constructed what it means to be a diva. After her return from a year-long tour, Hans Ulrich Obrist spoke with the singer about poetry, autonomy, and the importance of baby hair curls. In a shoot with Juergen Teller, she channeled the spirit of legendary voguer Willi Ninja.

HANS ULRICH OBRIST: You grew up with dance, and then switched to music. Was there an epiphany, or an awakening?

FKA TWIGS: I started dancing when I was eight years old, but when I was about fifteen, I realized that I didn’t really love dancing. I loved dancing to the music. That was when I first explored other ways of expressing myself. It grew for me gradually. I started going to a youth center in Gloucester and writing with the tutors there. It was a terrible studio – nothing really worked – but I was working with MCs. Then I moved to London and worked at a youth center in Barnsley. I was working in the studios with young people, teaching them how to write songs. But when I was about 22, the government cut all of the youth art funding in the borough. All of a sudden, I was jobless. It meant that I had to start focusing more on what I wanted to write about, rather than helping others express themselves.

You also have a background in cabaret and underground circus. You once said in an interview – one of your rare interviews – that those performances made you fearless, because they got you used to tough crowds.

I got involved in the underground circus and cabaret scene in London. I started off at The Box, which I guess is a more commercial venue, even though it’s still quite bizarre. They had the most amazing performers. People would come from Romanian circuses – these young girls who could wrap their legs around their necks and do all these crazy acts. Everyone made their own costumes, and it was on you to come up with your character. So I invented this sort of Betty Boop, Jessica Rabbit-style character. It was completely out of the box in terms of who I was as a young girl. I was quite boyish – and a little bit awkward – and I was discovering my own sexuality through this cabaret scene where I was encouraged to wear these tight dresses and do my hair in a certain way. I basically sang the same two songs for three years and that’s how I made my living and was able to go work in a studio. It made me feel really independent. I would have to make my own costumes and find ways of making these other people’s songs feel like my own. I didn’t realize it at the time, but that was the beginning of Twigs.

Who were some figures in music who inspired you?

I grew up in a very creative household. If I wanted to be a cat for a day, I could be a cat, and my mum would put a saucer of milk on the floor. My mum let me do whatever I wanted to do. I guess I relate it to something that Tyler The Creator once said. He said, “I’m a unicorn. Don’t tell me otherwise.” I was brought up in a household where that was true.

Your debut EP1 obviously marks the beginning of your music, but it also marks the beginning of your work with videos. How did that get started?

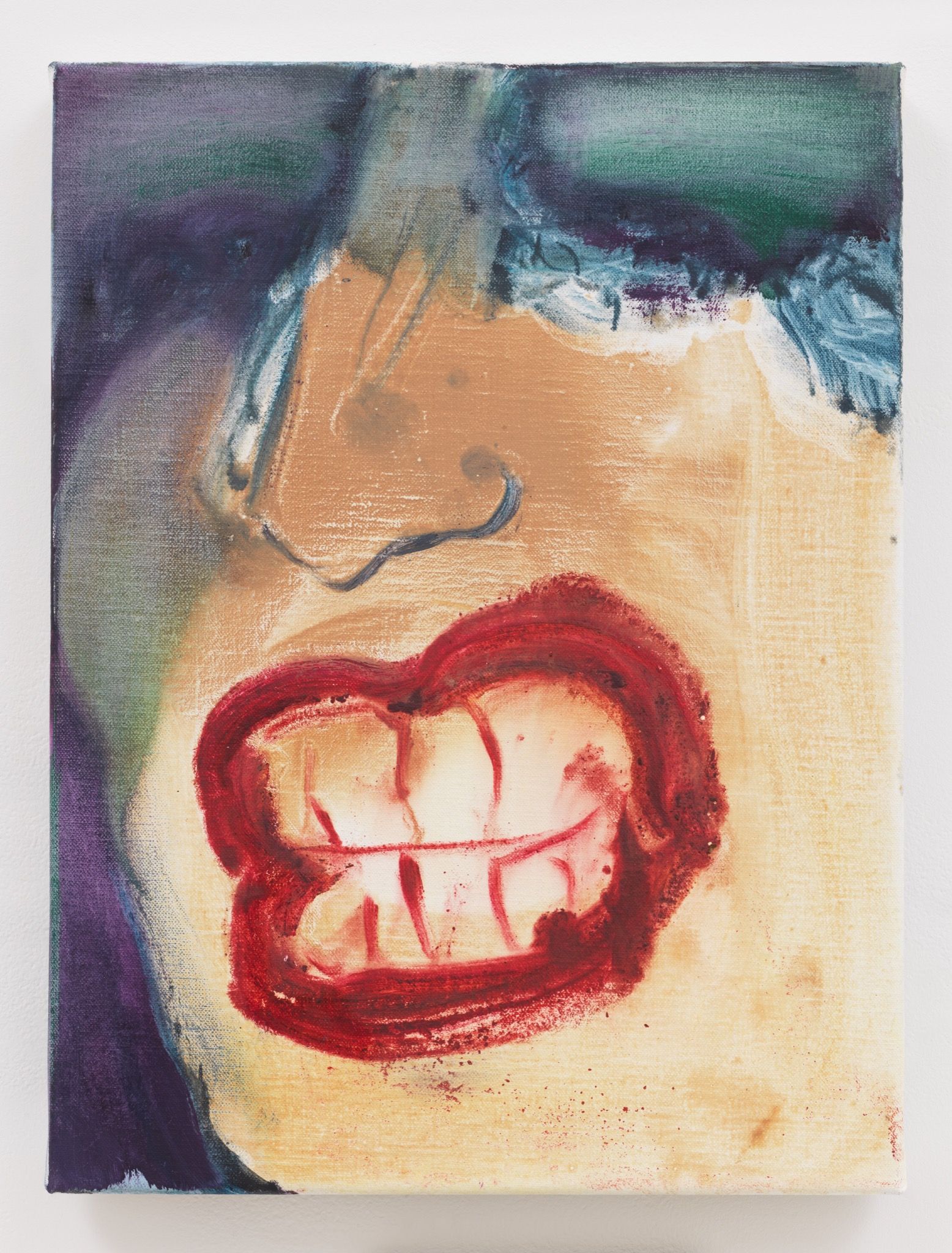

My voice is very high and very ethereal, but that’s not necessarily how I feel inside. So, for me, videos are about focusing on emotion as the antithesis of how something sounds – and I do that with music as well. If something is really powerful, and my voice is soft, that makes me happy. If the words are really obscene, but the melody’s really beautiful, I like that contrast. I worked with Tom Beard for “Papi Pacify,” and it was a concept that I’d had for ages. It was this big pile of hands in my mouth. I was in a relationship at the time where I felt really choked and I just felt that I wanted to show people how it can feel to be choked. Sometimes I think you can enjoy the way that someone stifles you. It’s so uncomfortable, but in a way, you enjoy that pain. But then I got to the point where I wanted to make the videos myself. If you’re coming up with the concept by yourself, and you’re writing the treatment, then all you need is people to explain the lighting and the camera stuff. Then you can build a team and learn how to do it yourself.

The idea of do-it-yourself is very important in your work. You often work on your laptop while you travel, co-producing your own sounds.

As a musical artist, it can be very easy to become a blur to people. Traditionally, in the music industry, men tell women what to write. Kate Bush was the first female artist to have a number one song that she had written herself, and that wasn’t even that long ago. As a female – and I don’t really like to talk about things “as a female” – you’re sometimes put in this position where someone tells you what to write, or how to portray what you’re feeling through the music. And I never wanted to do that. Every single lyric and every single melody you’ve heard is mine. How can I let somebody else portray how I’m feeling in terms of the sound? If I say to a producer, “We should have a guitar, and it should sound woozy. It has to sound really sad, like a wizard that’s just stabbed his son.” How is someone else going to know what that feels like? They do their best, but they don’t know. So I realized that I had to essentially do it myself.

For your album, LP1, you worked with a number of very distinctive producers from your generation – Devonté Hynes, Arca, Clams Casino. How did you manage to work with them while retaining this commitment to self-expression?

I have a very specific sonic palette. I know what fits into it, and I know what doesn’t. When somebody asks me to try something, and I know that I’m not going to like it, I’m going to say no. If I don’t like it, then what’s the point in trying it? We’re not at school. So the album was more like a funnel. I started off working with a lot of people, doing sessions in the beginning with Devonté Hynes, Clams Casino, Arca. We started with everyone working on a track together in some way, and then when I was finishing the record, it slimmed down to the point where it was just me in the room with my band-mate Cyan. It was quite an isolating process, but in the end, I think I needed that isolation to do it and learn something.

I spoke the other day to Patti Smith about the importance of linking music and poetry in composition. So I was amazed to see that your album started with this quotation from a poem by Thomas Wyatt, “I love another, and thus I hate myself.” How do you connect to poetry?

That line from Wyatt rang so true to me in light of everything that had happened in my life over the past few years. My mum had some health problems, and I loved her so much and I wanted her to get better. Then I hated myself, because I couldn’t do everything to right it. And I loved a guy so much that he made me feel jealous. He made me feel so ugly inside, so I hated the person that I had become through trying to love him. And then, with my producing, I had all these ideas in my head, but, at the beginning of making my record, I just didn’t have the skill level to put it out. I’d hate myself because I felt so silly. So I started to think about what I was doing, “I love another, and thus I hate myself.” It wasn’t the title of my record, but it was certainly kind of a subtitle to how I had been feeling.

I’ve spent hours listening to LP1.

LP1 was a satire of my life. It’s how I felt going through heartache and just trying to grow – mainly as a person, not even as an artist. As a young female, it can be quite hard accepting love’s challenges – realizing that you’re not a child anymore, that all that support is somehow gone. You’re turning to the world, and you’re like: “Wow, this is it. This is life.” That’s what I was going through when I wrote the record, and I just wanted to be as honest as possible.

You’re just at the end of a very long tour through the US, during which you made an amazing – and very unusual – appearance on The Tonight Show with Jimmy Fallon. How did that come about?

I had been struggling with the idea of doing TV stuff for a while, because you perform on a stage where so many people have performed before. I just wanted to be myself. My friend Leo Velasquez showed me a video by an artist called Daniel Wurtzel, and he was like, “Maybe you should try that for a video.” And I said, “No, let’s do it live.” So we bought this organza, and it was just blowing everywhere. We did it in dress rehearsal, and the organza won the battle. It was all over me. I had these big heels on and I was getting twisted in it. But when I went upstairs, I watched the recording of the rehearsal and realized, “When you’re in control of something, and not put off by what people say, and not put off by their ideas, then that’s when you win.” Because every single time I took the organza and I threw it, that’s when it looked the best. I didn’t really have time to practice that. But I practiced it on television, and it worked.

Do you picture your performances as being full-on environments as opposed to concerts? In a sense, the Tonight Show performance was a type of Gesamtkunstwerk.

I definitely see everything I do as a 360 experience. I want to give myself a challenge. Like, why not try and sing whilst having twelve fans blowing at high speed in my face? Why not try and do that? Being an artist is about trying things and accepting the challenge. I like putting myself in an environment where I can be nervous. I like to have an extra element, even if it’s just a rowdy crowd. I get a kick out of a tough crowd.

As an artist, what is it like for you to spend large chunks of time in a nomadic state on tour?

When I’m away on tour, and I’m not making music, I can get really, really down. I’m in a different hotel the whole time, or sleeping on a bus for seven weeks. It’s not very glamorous – not at my level. It’s me waking up on a bus, getting off the bus, walking to a tiny hotel room, not being able to eat good food, washing myself with itchy soap, not knowing where I am. I find it difficult to have ideas, because I’m not centered, so it just doesn’t do anything for me creatively. It’s not a 360 experience anymore. Touring is so important, especially as you get bigger, but sometimes it makes me doubt my future as an artist.

Your project with Google Glass brought your work to a new, commercial context. How did that project come about?

Google approached me and asked me to make this ad about Google Glass. And my first reaction was like: “Why would I do that? That’s ridiculous!” And then they asked me again, and I was like: “No. Stop hitting me up! Stop hitting me up!” And then they asked again, and I thought, “Maybe I’m setting too many boundaries on myself.” Because I’m sitting here with all my cool friends, and all my cool clothes, and I need to branch out of that. That corporation is one of the biggest organizations in the world. Why wouldn’t I do this when it’s actually an amazing opportunity?

Then what happened?

So I agreed to meet with them in LA. I went into this sort of “glass haven,” and they showed me all these glasses and how they worked. I had an idea straight away. Then they said, “Well, do you want to do it?” And I said: “Yes, I do. But you have to let me do whatever I want.” Working with an artist like myself, I think they knew that would be the deal. I wanted the video to play on how people see me. I wanted to put a full stop on a style that I had developed over the past two years, so I could move on to a different chapter in my life. Because sometimes I’d be walking down the street and someone would say: “I didn’t realize you were real. Like, I thought you were just this thing on the computer.” So, in the video, I’m saying all these goofy words, because I know that’s how people want me to be. I’m actually kind of worried about speaking gigs, because it’s disappointing to people that I’m just a human.

What exactly were you putting a “full stop” on? What was this image of yours that you were moving on from?

For me, it was a way of reclaiming something that was very personal. We found all these cute mixed race girls that could krump and vogue. They were amazing dancers – like even better dancers than I am – and we put them in an identity that I had really connected with myself. They were all wearing clothes that I had worn before. It was almost like I was mocking myself, but it was also the end of an era for me. Before I had the finances, the way I did my hair and the way I styled my cheap jewelry was my way of dressing up and feeling like an individual. During my time in this underground circus and cabaret scene, I was inspired by Josephine Baker to style my hair with baby hair curls. I don’t think I was the first person to ever do that. I completely know that chola girls have been doing that for years, and it sounds silly because it’s only a hairstyle, but when you don’t come from a place where you can always buy everything, these tiny things matter to you. I really took the time to do the patterns and make them a-symmetric in an intricate way. No one else was doing it, and now everybody does. I think it’s a really great thing, but at the same time, it’s something you have to let go of. Now it belongs to Givenchy, or it belongs to Jean Paul Gaultier, or it belongs to Katy Perry. You let something go, and it becomes the world’s.

The styling statements you’ve made in your videos and performances have turned you into a fashion figure as well as musical figure. Is fashion something you’re passionate about?

For me, it’s definitely a side thing. I really don’t like trying on clothes. I don’t like being told what to wear, either. My stylist, Karen Clarkson, is one of my best friends and she makes sure that, when I turn up at a shoot, I don’t feel like a commodity. To be honest with you, when I do shoots, I feel like I’d rather be in the studio making music, or I’d rather be reading.

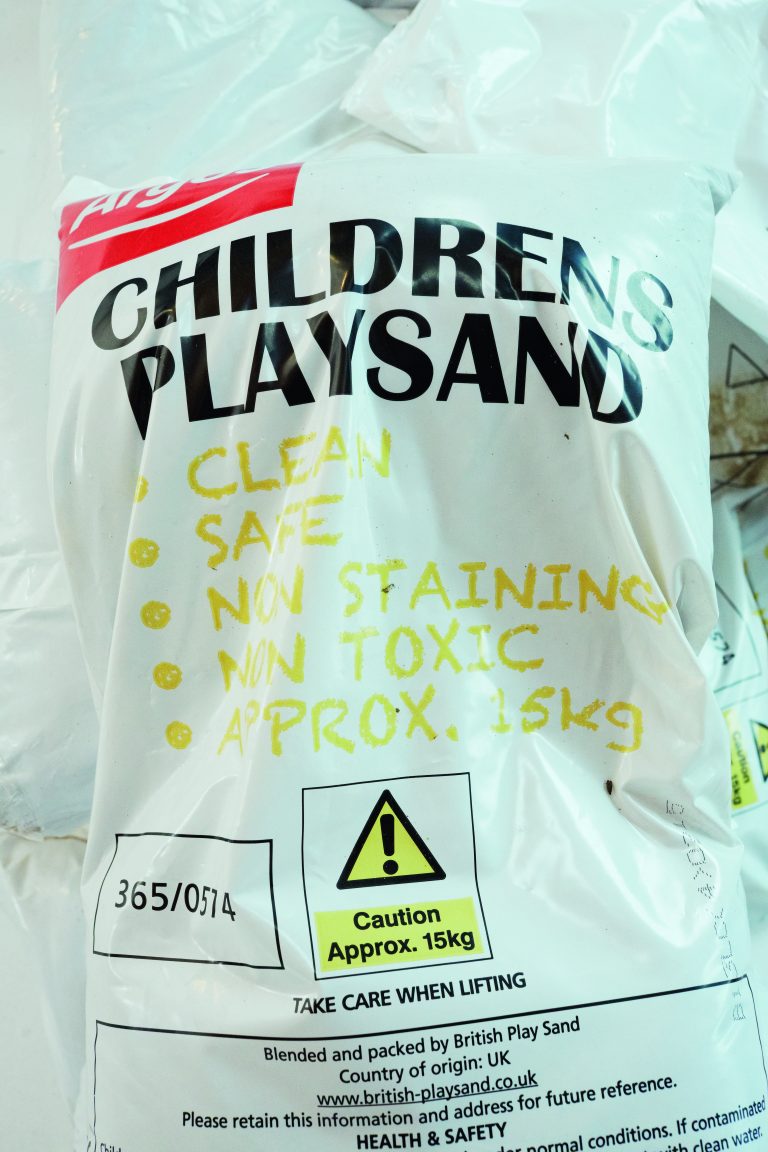

Tell me about your shoot with Juergen Teller. Given your futuristic style, it was surprising to see you in an environment filled with tree branches and playground sand.

Juergen was inspired from watching my “Glass & Patron” video that had just come out. In that video, I had taken an artificial environment – the runway of a vogue ball – and plonked it in the middle of an organic environment. So he wanted to do the opposite and take a part of nature and put it into a sort of controlled, man-made setting.

And you also directed that video. What inspired you to recreate the choreography and atmosphere of ballroom voguing?

Voguing has given me the opportunity to find a freedom within my body that I never found when I was a dancer. When I worked professionally as a dancer, I was what is known as a “choreo-head.” A choreo-head is a dancer in the commercial industry that can pick up choreography yet doesn’t really have a specific style that they can call their own. I was classically trained, which meant that I had a core basis of technique, but I never really found a dance style that I loved. I was quite into krump, but I never had a complete breakthrough with it. Then, about three years ago, I started going to vogue nights in New York. I felt such a connection to what they were doing, and I was so frustrated that my body wouldn’t do it. It was the most beautiful thing I’d ever seen. With vogue, you can bring a very feminine poise to anything. It can be cheeky. It can be sexy. It can be smooth. You can be cocky. You can be vulnerable. Anything. And I think that’s something I really try to portray in my work as well, no matter what I do.

For the shoot with Juergen Teller, you dressed up as Willi Ninja, the legendary voguer who kind of popularized the genre. Why did you decide to pay homage to him in particular?

I always really loved how Willi Ninja looked, but I didn’t know much about him from a personal point of view – except for Paris is Burning, which is the reference point everyone goes to. But when I did the “Glass & Patron” video, I had the pleasure of meeting Javier Ninja, who’s now the current father of the House of Ninja. I was able to talk to Javier first-hand about the type of person Willi was, through people that he knew and their experiences – why he was such a legend in voguing and why he was able to bring it to the forefront of culture. Another thing that I really loved about Willi Ninja was how he had this very feminine sense of dress, but at the same time maintained a sort of masculine elegance to the way he danced. I thought that it would be really interesting to dress up as a man embracing his feminine side, which is a complicated kind of challenge.

It’s very interesting from the perspective of gender, because you’re a woman who’s emulating a male dancer who studied traditionally feminine gestures. It’s a process that’s moving through so many filters of identity.

You know, I’ve always found it very difficult to connect to myself as a woman. I think it’s because I’m very petite, and I look so young without makeup. But these boys that I’ve met through voguing – like Jamal Prodigy and Benjamin Milan, who did the movement direction for the shoot – have helped me overcome this problem I’ve had connecting to my womanliness. It’s really interesting how a man in touch with his feminine side can help a girl who needs encouragement. It proves that things don’t have to be so rigid anymore.

Do you feel as though tight-knit, in-person subcultures – like the culture of balls and voguing – are becoming extinct in the age of digital media?

For me, I often found it difficult to learn something new when every time I try a new dance on stage it goes on YouTube and automatically has like 30,000 views. In that sense, vogue was the best thing that ever happened to me, because it made me get over myself as a dancer. I’ve now realized that none of that other stuff exists. If you can’t touch it, it’s not real. Can you touch Instagram? No. It’s not real. Can you touch Twitter? No. So it’s not real. Can you touch YouTube? No. So it’s not real. The only thing that’s real is when you’re in that moment – when you’re dancing, or you’re performing, or you’re expressing yourself. Those other things are not real.

Have there been times when over-exposure has kept you from growing as an artist?

Someone once told me that the age when you become famous is the age that you will stay for the rest of your life. So, if you get famous at sixteen, your personality will stay sixteen. I’ve become very well-known at 27, and I’ll be damned if I stay 27.

You’ve mentioned that the Internet does not feel real to you, but you exist online in a major way. How do you relate to technology?

For me, it’s always been about embracing the way I get myself out there as an artist. I was the last kid at my school to get a computer, and I still find it difficult to program things. It doesn’t come very naturally to me. But, in terms of the Internet, I saw that I had one video on YouTube that had 80,000 views within six months, which isn’t really a lot compared to other pop stars, but for someone that had never put out any music before, that was a huge thing. So, for me, it was about getting over my fears and embracing something that initially felt very intimidating. When I first put on Google Glass, I thought about how I could move my arms and my legs without dropping my iPad, or something. As a dancer, I was thinking, “If my friend sends me a dance move, then I can learn it.” I can’t go a 110 percent, but I can learn it. I think that’s an amazing piece of technology. As a creative, it’s about being able to take advantage of something that’s there to help you.

Do you ever feel as though your work is structured by the parameters of the music industry?

When I was fifteen years old, my mum took me to an A&R she had found through a cheesy performing arts newspaper. I sang for him, and he gave me a five out of ten for my singing voice. He then told me, “If you want to be a singer, this is what you’ve got to do. You do your first song, a pop song, and we’ve got loads of pop writers who can do that. Then, you do your second song, a ballad, and we’ve also got loads of ballad writers who can do that. Then your third song is a collaboration. And then the fourth song is a cover.” It sounds ridiculous, but that was the formula for so many years. But then the Internet came – and YouTube came, and things like Spotify came – and it just blew that out of the water. If people don’t like something, they’re not going to click. The industry can’t control that anymore. For an artist like myself, I could release my first EPs and not really have any hype about it. I could release my album and not necessarily have a hit single on it. Everything is structured so differently now. And, as a music artist, it means that you can have a career that’s 100 percent yours. That’s something I’m coming to terms with and really enjoying now.

As you grow more famous, has it become harder to maintain that autonomy?

No. It gets easier. If I don’t want to do something, then there’s no way anyone’s getting me to do it.

Credits

- Interview: Hans Ulrich Obrist

- Photography: Juergen Teller