Finding Meaning in an Image

Berlin-based artist Ketuta Alexi-Meskhishvili likes to manipulates images—but not through Facetune or AI, as you might expect in our contemporary visual landscape. For Alexi-Meskhishvili, who was born in Georgia before emigrating with her family to the US in the 1990s, photographic manipulation starts the very moment the picture is being taken. The artists blurs the boundaries between digital and analog photography—working with either camera and then manipulating the shot images with either analog or digital methods respectively, including scratching, cropping, or adding handmade marks. She thereby challenges conventional notions of photographic reproduction and what image-making can mean today.

Portrait by Alex de Brabant

For our current Spring/Summer 2025 collection, Alexi-Meskhishvili designed a flower pattern that she likewise manipulated. In conversation with Claire Koron Elat, she talked about the process behind the design, flowers that are politically charged, and how she consumes images.

Ketuta T-Shirt availble HERE.

Alexi-Meskhishvili's pattern for 032c SS-25 on Meadow Walker.

Alexi-Meskhishvili's pattern for 032c SS-25 on Habib Masovic.

Claire Koron Elat: Flowers are a recurring motif in your artistic practice. Could you explain the background of using flowers as a visual element?

Ketuta Alexi-Meskhishvili: I grew up in the Soviet Georgia, where you only had two types of postcards—either with a communist leaders or of flowers. My first exhibition in Berlin ten years ago was called “German Flowers.” For that exhibition, I photographed as well as found images of flowers and worked them in various ways—digital and analog. I realized then that flowers read as this really neutral thing, and also as something, along with photographs of babies and pets, that is not taken seriously and I wanted to play with that. Later, during the COVID lockdown, I started taking Polaroids of flowers, because flower stores were one of the few stores that were open. So, I started taking two Polaroids of a flower every evening and then putting the Polaroids in a drawer overnight, waiting till the next morning to look at them. It was a moment of surprise or improvisation in this very planned military time of the lockdown. During that time, flowers took on the meaning of rebirth, hope, and resistance.

So, in my last exhibition at LC QUEISSER in Georgia, I purposefully started using images of tulips. It’s a symbol of resistance there. In 1989, there was a student uprising against the Russian occupation and people were killed by the Russian military. The red tulip kind of became a symbol of this moment, which snowballed into all these Republics getting independent. So, it can have multiple meanings. It can mean nothing, but it can also mean a lot. And tulips mean different things in different cultures. In Iran, it’s apparently a sign of martyrdom. And in Holland, the first financial bubble that burst was based on tulip trade, where there was a high demand, and then things were overproduced, and there was a crash. I also like the fact that it is considered feminine, kitsch, and decorative but can still have depth and meaning.

CKE: The fact that flowers are these feminine, delicate objects and simultaneously highly politically charged, is quite a contrast. Do you think this can work together?

KAM: I welcome the lack of clarity. My favorite thing is when things exist in between definitions.

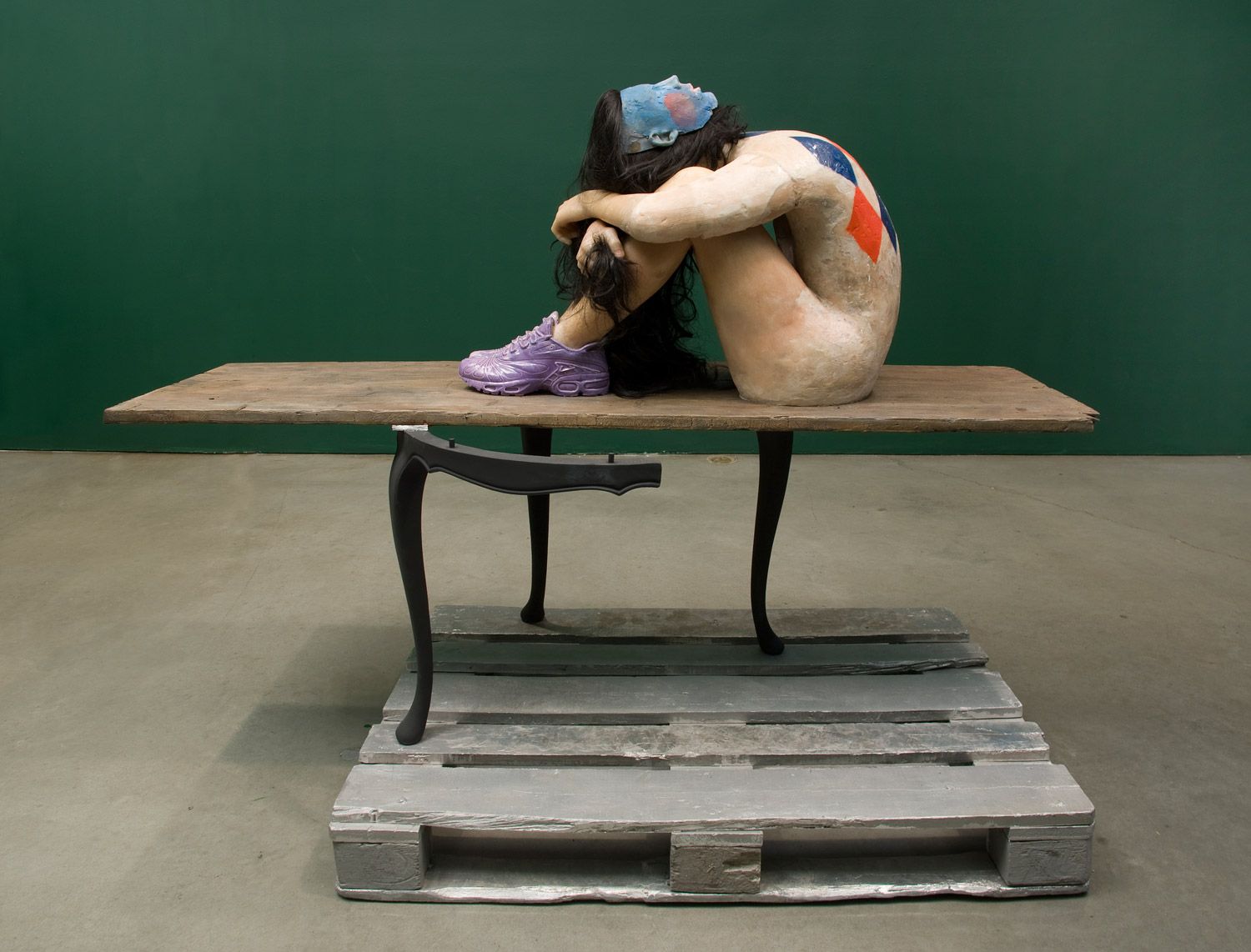

“flush,” Galerie Molitor

CKE: Do you think the fact that flowers are regarded as feminine also means that using them as a motif results in some kind of feminist commentary?

KAM: I don’t know if that’s necessarily something I intend, but it’s in there. Also, since it’s a decorative motif, it’s something that you would usually find on textiles and textiles were historically done by women.

CKE: You also used this motif for a few garments that were part of our Spring/Summer 2025 collection. What was the process behind designing this?

KAM: It started with a fabric that I found—a kind of anonymous piece of cotton that I found somewhere with pink roses. I proceeded to put this fabric directly onto an analog negative, which is quite big, and then exposed it with a little LED finger light. These finger lights are usually used for raving. I work in total darkness and as I move my hand over the negative with the LED light, the image records that gesture. You can see the movement of my hand in the image—where it’s really bright, it’s the movement of my hand. In this case, it was a green LED light, as I wanted it to be neon green and somewhat off-putting. After I scanned the negative, Maria reworked it a bit for the garment pieces, and it got a bit darker.

“flush,” Galerie Molitor

In terms of photography, I am curious about how the context can change the meaning of an image, how you could have a photograph in a gallery on a white wall or you could have it on an advertising billboard. You can have it in a magazine, a newspaper, on a binder, and the image changes. So it was curious to see what it would be like on a piece of a garment.

CKE: You also work with textiles in your artistic practice. Would you distinguish between textiles that you show in an exhibition versus textiles that are being worn by someone?

KAM: I distinguish them in that I have full control over the textiles that I exhibit. For example, in, “there, but not" in the Kunstverein Braunschweig, I created a copy of an exhibition room out of photographs printed on transparent textiles which I planned in detail. I don’t have that control over a garment, designed and cut by someone else. However that’s also interesting to me—to let go of control and let an image transform and become something else. Although art and fashion feed each other, fashion has to be functional while art does not.

CKE: The way you achieved this pattern is similar to how you treat your photography, which is often a combination of using digital and analog methods. What are the differences when you take an analog vs a digital photograph?

KAM: In analog photography, there is a lot more space for improvisation, ambiguity, and mistakes. There is space for surprises to happen that you did not plan. In digital photography, you have full control. In analog, there’s a larger process of discovery. There’s an imperfection in analog that you don’t have in ones and zeros.

"there, but not" Kunstverein Braunschweig, courtesy Ketuta Alexi-Meskhishvili, LC Queisser, Molitor and galerie frank elbaz

CKE: It’s an interesting topic because we live in an age where everyone is a photographer and where everyone is also able to digitally alter images or even generate images with AI.

KAM: At this point, you can’t even take a “bad” photo with a phone—it autocorrects the light settings for you. I think what the ascent of AI and these enhancing technologies have proven is that photography was never objective. You could angle your camera in a certain way to show what you wanted and control the narrative. Now, you can fully make up the narrative. But for me, photography has never been about depicting reality. In its reproducibility, I always try to find some kind of subjectivity. I might be a masochist, because I work with photography, which is a reproducible, flat medium, but I’m always trying to find to some kind of depth and subjectivity in it, which is not naturally inherent to the medium. I battle with it all the time.

CKE: When you engage in these abstract forms of image making, is this a way of creating your own world?

KAM: When I make work, I try not to think—I go into a kind of a trance. It’s also part of the process of working with a large format camera. It’s a very burdensome camera, and it takes a long time to set up. Film is also expensive. So, there is a sense of slowing down and paying attention to detail that I enjoy. I tend to go into a trance with an object or the scene that I’m photographing. It’s not like a snapshot. It’s therapeutic for me. It can last for hours. It’s a non-verbal way of communicating with the world. And sometimes I don’t even understand how it works. I grew up looking at fashion images, and I’ve paid attention to how things work in a larger context and in culture, but with my work, I don’t think about the impact it’s going to have, I just go with my gut most of the time. It is quite personal.

CKE: How do you observe your own consumer behavior?

KAM: I consume a lot of visual culture, maybe thousands of images per day and I wonder what the difference is between the impact of one image and the next. I can see a picture of war, and I can see a picture of a shoe, and it is all presented in the same rhythm. In the end, it desensitizes you to things. Finding meaning in a visual image is like finding a treasure.

“flush,” Galerie Molitor

Ketuta Alexi-Meskhishvili's exhibition “there, but not” at Kunstverein Braunschweig is open until July 1, 2025.

Related Products

Related Content

Société de 032c: Artist KETUTA ALEXI-MESKHISHVILI on Brazlian Novelist Clarice Lispector

EVERYTHING COUNTS: 032c Readytowear Spring/Summer 2025

ANDRO WEKUA

Dark Matter: ANDRO WEKUA

Young Gallerists: A Roundtable on Founding a Gallery in Today’s Uber-saturated Market

Black Internet: Allen-Golder Carpenter and the Parable of the White Folding Chair

Dozie Kanu: EVIL

Heji Shin's AMERICA