Black Internet: Allen-Golder Carpenter and the Parable of the White Folding Chair

|JARD LEREBOURS

In the hands of the right person, a single white folding chair can incite revolution. Spurred by the Montgomery Riverfront brawl, Allen-Golder Carpenter began developing their seminal video piece Black Internet in August 2023. Featured recently in the exhibition “Content Industrial Complex” at the 032c Gallery, Black Internet sources Black meme culture, footage of drill rappers, and archival video of the late MLK to explore Black liberation and structural violence.

In just the past year, Carpenter has shown work in exhibitions at Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler and HOUSE in Berlin, as well as performing alongside Blackhaine at the iconic Volksbühne theater. Working with sculpture, installation, video, and sound pieces, Carpenter’s work brings their experience of growing up Black in the DMV (District of Columbia, Maryland, Virginia) to the forefront. Carpenter pays homage to the Black revolutionaries before them, honoring the living legends among us and recontextualizing the fashion, culture, objects, and sounds of their hood.

In conversation with Jard Lerebours, Allen-Golder Carpenter talks about the afterlife of Black memes, freedom of the press, MLK, and cultural gatekeeping.

Allen-Golder Carpenter, Black Internet, 2023-2024. Courtesy the artist

JARD LEREBOURS: Is the internet segregated?

ALLEN-GOLDER CARPENTER: Yes, a thousand percent. It’s definitely segregated, people in general have this way of self-regulating. Most people’s internet experience tends to be like an echo chamber of whatever their direct beliefs and perspectives are. I try my best to engage with as many different opinions and perspectives and read things by people that I directly disagree with. It only helps to make your own point of view stronger, because, when interrogated, you’re able to actually defend it, you know what I’m saying?

JL: Where can we find the Black internet?

AGC: The password is knowing it exists.

JL: Are you pro or anti internet segregation?

AGC: The first thing that comes to mind is that people are now making an argument to bring back gatekeeping. I’ve been seeing how many Black cultural markers are absorbed and blown up then stripped of their origin. It happens so often that I’m in favor of gatekeeping.

But, at the end of the day, that’s just how culture works. Culture isn’t like a vacuum seal. It has its way of spreading and leaking out and dripping and splashing onto other things. Once something leaks out, you just continue to fill it with new things. Culture continues and new things continue to be created.

Allen-Golder Carpenter, Black Internet, video installation part of "Content Industrial Content," 032c Gallery, Berlin, 2024. Courtesy 032c Gallery

JL: Talking about the internet and this idea of culture leaking out, your piece Black Internet explores structural violence, temporality, and death in relation to Black life in online and meme culture.A lot of your work and practice engages with ancestor worship and veneration. How does Black Internet continue that work?

AGC: A lot of what I’m trying to do is reframe the way people look at certain things in Black culture, by putting canonical images next to hyper contemporary ones. I’ll position MLK next to drill rappers. The internet moves at such a fast pace that things just kind of come and go and a lot of things slip through the cracks. The point is to honor things that are happening right now. History is happening every second of every day and you yourself will be an ancestor one day.

I’m always asking people to take a second to understand what they’re looking at on a deeper level. Like, yeah, you laughed at this meme, but why are you laughing at this meme? Where did this meme come from and what are the implications and the aftermath of when it leaves?

JL: You mentioned the canon versus these more hyper contemporary images, how was the process of sourcing material for Black Internet different than your sculptural work?

AGC: Things have a way of finding me. I joke that I’m on my phone all the time anyway so I might as well put it to use. I purposely seek things out and people send me things. People love sending me things because they know I’ll use them. I was thinking about how to make this video as Black and as DC as possible.

The thing about video is that the size is only limited to how much your hard drive can hold. I stopped sculpting in a traditional way because I kind of ran out of space. The thing is, the internet and Black culture on the internet is an ever-expanding thing that escapes the confines of what can be depicted in sculpture, at least in real time. When a video comes out and goes viral, I can synthesize it that same day.

Allen Golder Carpenter, Foundation 2, No Gallery, Berlin, 2023. Cement, concrete, stalking caps, aerosol paint, steel 88 x 20 x 20 in. Photo courtesy of No Gallery and Andy Guerrero

JL: I’ve had the pleasure of seeing earlier iterations of Black Internet and now this final piece. I’m curious about the origin story behind it and some big changes that have happened between different versions.

AGC: So the piece was first inspired by the viral video of the Montgomery Riverfront brawl. For the uninitiated who might be reading this, essentially a bunch of Black people fought off these racially motivated white attackers with folding chairs. These chairs became the subject of many memes that permeated the Black side of the internet for a week straight. The brawl happened in Montgomery, Alabama, most notably known for the mass peaceful demonstration by MLK where he marched from Selma. At some point, I was even thinking about getting a folding chair tattoo.

The title of the exhibition that the video was in, “Content Industrial Complex,” was about how memes and content are constantly getting pushed out and replaced by the next new thing. I remember thinking about how the brawl video was kind of ubiquitous in one space, but then obscure outside of it. Even after people moved on, many of the Black people in that

video caught charges and the repercussions live on long after the meme actually dies.

But to get back to what you said about this being the final version, what you’ve seen is the version for exhibition, not the final version. There is no final version. I fully intend for Black Internet to be a living artwork.

JL: I really love this idea. It makes me think of your installation Viewer vs. Subject: Projection + Boundaries. How did your audience react to being captured in that work?

AGC: The original intention was to invoke a sense of unease and anxiety, like being watched. The audience is being put on the same plane as these images of shoplifters that I’d collected. But the crazy thing is that people actually kind of enjoyed it, a lot more than I anticipated. There were even cases where people were coming by the gallery every week to see if they had made the wall. It almost ended up becoming this vanity thing.

Many of the people in that display are members of the owning class, i.e. the people that directly benefit from surveillance technology. They will never be on the negative receiving end of surveillance, so for them it was amusing. The framing device that is the gallery kind of makes a social experiment like this borderline impossible. You can’t shame someone by putting their face in a place they want to be.

Installation views of Allen Golder Carpenter "Viewer vs. Subject: Projection + Boundaries," Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler, Berlin, 2024. Courtesy the artist

JL: Thinking about that piece as a form of documentation, is your practice informed by journalism and documentary?

AGC: My greatest fear is that things will be lost and forgotten.I want to be a steward of those things. If I ever went back to school, it would be to study to be a librarian or some kind of archivist. I just watched this YouTube video on how we have a moral obligation to preserve things and to preserve media. There is no freedom without journalism. I recently learned from a documentary that during the Great Migration, a big driving force was The Chicago Defender, a Black newspaper which was smuggled down South on trainlines by Black train car porters. It was pretty much calling people from the South to come and create new lives up north.

Without Black people coming to urban centers up north like Chicago, Detroit, and New York, we wouldn’t have any of the contemporary Black culture we have today. We wouldn’t have rap music coming out of New York or Motown records in Detroit. Without Emmet Till, a young Black boy going from Chicago to visit his family in Mississippi, and his disfigured image being put in Jet magazine, we might’ve never had the kickoff for the Civil rights movements.

I think the real reason they tried to ban TikTok is because it gave young people radical unfettered access to journalistic expression and accessibility to reach audiences larger than major news outlets. A kid could get on TikTok and show you what’s really going on, tell you how hungry they are. On the major news outlet, some fucking stiff is going to get on TV for the 10 o’clock news and try and tell you why that kid isn’t actually hungry.

Installation views of Allen-Golder Carpenter "Viewer vs. Subject: Projection + Boundaries," Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler, Berlin, 2024. Courtesy the artist

JL: You use footage and images of historical figures such as MLK. There’s this triptych of yours that features Black men pouring out one for the homie as a practice of libation with MLK’s’s casket to the side. How do you honor and love MLK while simultaneously critiquing his nonviolent approach?

AGC: Before I get into that, the video is by a rapper from my neighborhood pouring one out for another rapper from my neighborhood. Like, these rappers were at my high school graduation, you know what I’m saying? To use another canonical name like MLK, I think bell hooks said something like you’re allowed to critique the things you love. I think that constructive criticism is one of the deepest forms of love.

The point of this entire video is that you can disagree and reevaluate the positions of figures in the canon without discarding them.We’ve all encountered people that think their argument is infallible just because they attached a quote from some big name in theory like what I just did with that bell hooks quote.

I love MLK and bell hooks but I think they were wrong about some shit. We don’t need to deify and romanticize people. People will be wrong about shit, and that’s okay, that doesn’t mean you just disregard everything they ever did.

Allen-Golder Carpenter, Stone Soldier 1, 2021. Cement, dress shirt, aerosol paint, plastic, steel. Courtesy the artist

JL: I think that’s an important practice too because it teaches us to not discard people in real life too. Getting back to MLK: Do you see his ideology evolving or being reinterpreted by today’s world?

AGC: I see more questioning of it. I also definitely think that they whitewashed the hell out of him and heavily pacified him in the way they teach about him. They love to leave out all the anti-imperialism and anti-colonial rhetoric that he was espousing while he was alive. They’ll name roads and all the Black neighborhoods MLK Boulevard, MLK this and MLK that, but they’re not really going to educate you about who he was as a person.

JL: MLK wanted poverty to be eliminated, you know what I mean? He was really about it. One thing that stood out to me in the video was your usage of the Under Armour logo. I know that you’ve made pieces in the past that examine your relationship to Black Air Force Ones and Nike Foamposites. I’m wondering more about the significance of the logo.

AGC: A friend of mine asked me about that and a lot of people think it has to do with the recent Balenciaga collaboration with Under Armour. It does in an indirect way. I wanted to sink Under Armour back to how it’s understood where I’m from. The fashion industry has a way of absorbing aesthetics from other people, Black people primarily. It takes them to a place where people don’t even know where the fashion came from. Under Armour was founded in Washington, DC, their headquarters are in Baltimore. In DC, Under Armour is some OG streetwear shit. Niggas be in the streets wearing full Under Armour outfits, rappers in videos wearing full Under Armour outfits. You go down to the south side of DC, you gone see what I’m talking about.

Another part of my fascination with it is that a lot of people don’t know that Under Armour is a very conservative company. They endorsed Donald Trump. Before they focused on athletes, Under Armour heavily catered to law enforcement. I’m fascinated by it being a staple in the hood, but then a staple among law enforcement too. These two groups are at odds with each other and then also somehow existing in the high fashion space together? That’s why I superimposed it in that place in the video. It’s kind of the same as when you watch a news clip and you see the news channel logo in the corner superimposed. I’m using that Under Armour logo to kind of suggest that what you’re watching is coming through my lens. It’s a reminder of where I’m from. I’m trying to bring where I’m from into every space that I’m in.

JL: You have a video of DC rapper MoneyMarr in Black Internet. How does his career and the backlash towards his alleged queerness relate to your ongoing examination of Black masculinity?

AGC: I think the way you even asked that question kind of answers itself. That situation is the crux of a lot of my art practice. MoneyMarr had his street image but then people circulated these old videos of him acting in what they deemed to be a feminine or gay way, and a lot of people turned on him at least in the area he was from. He lost his street cred essentially, and I don’t even think it matters if he’s gay or not. That just kind of echoes my own experience of existing as an alternative to these expectations that were placed on me as someone born a Black male.

It’s a testament to the video being a living work, I had no idea that situation happened when I made the video.

As an artwork, Black Internet has repercussions within it that I don’t even fully understand. This concept of manhood and the expectations of gender and sex are something that I’ve come to have this tenuous relationship to. It all comes down to how people see you. I’ve identified as gender non-conforming for a long time but since I don’t fit a certain aesthetic of what people associate with that, people automatically assume that I’m something different

Installation views of STREETSPACE BANGER, Kunsthalle Recklinghausen, 2024, courtesy of the artist and TICK TACK, Antwerp.

JL: I’ve noticed that you’re very aware of the fact that your audience is not explicitly Black or even American. What has your experience been as a Black person making Black art in the art world?

AGC: Other than the stuff you would kind of already expect, there’s a language thing. There are ways in which the work is talked about, the term identity gets slapped onto anything where the faces aren’t white.

I think the term “Black body,” for example, is a violent racist term because there’s no equivalent “white body” term. You don’t use the word bodies to describe the living, you use it to refer to the dead. I already knew what I was getting into and, for the most part, a lot of it is white people thinking that they understand your work a lot better than they actually do or ever could.

I just wish they would admit that they don’t understand.

I think the first step to understanding others is to admit that you don’t, and I made a densely Black coded layered video knowing that it was very culturally opaque. But I wanted to use that dissonance and understanding between the viewer and the work as artistic material itself. I think the fullest form of understanding that can exist between two people is knowing that no such thing actually exists. There are things that you simply cannot understand and that’s okay.

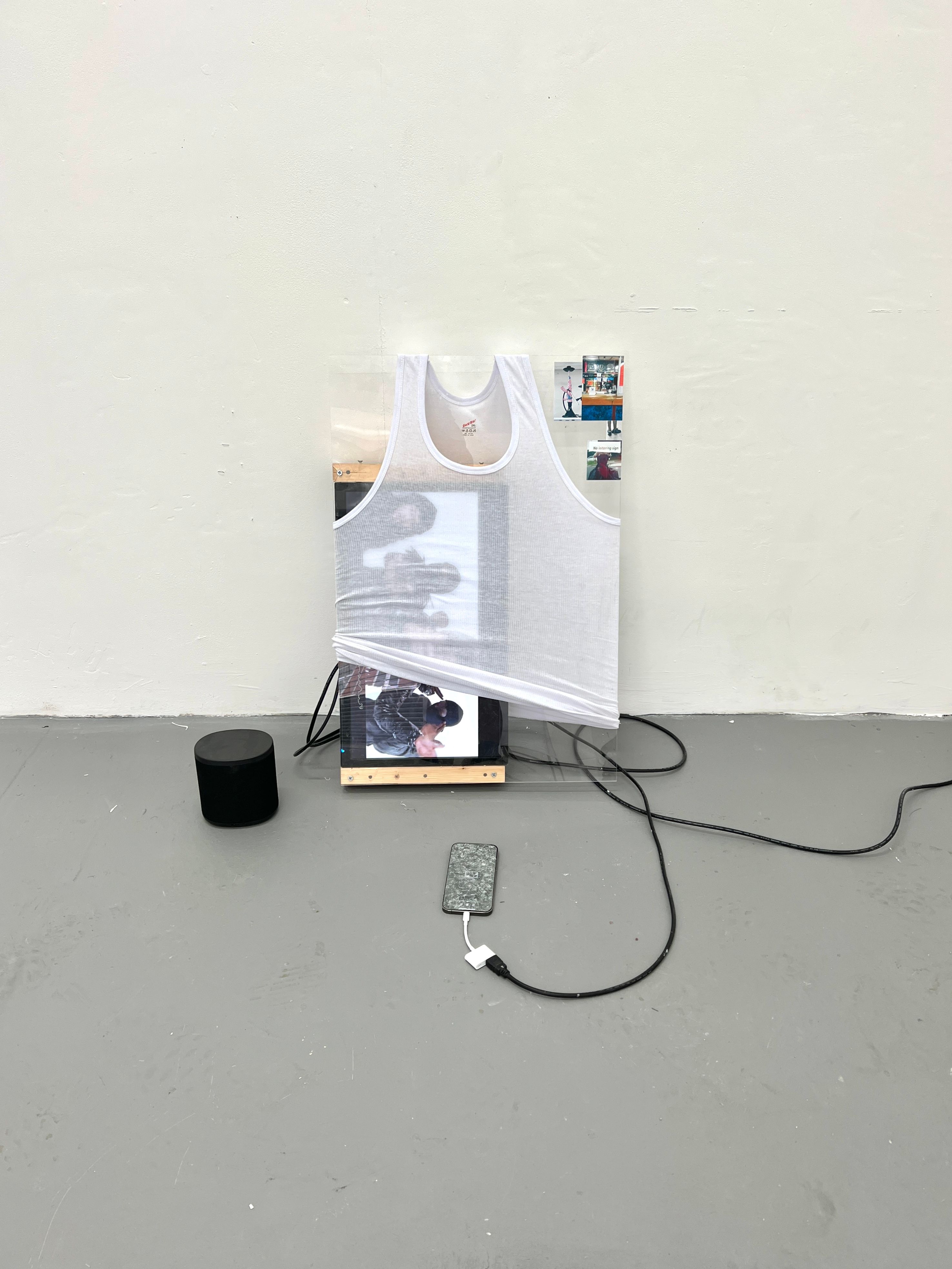

Allen-Golder Carpenter, Ghetto Body Surrogate V3 (don't beat on the counter) 2023. Perspex, cotton shirt, speaker, wood, steel, inkjet prints on photo paper, monitor, cables, iPhone, screen protector. Courtesy the artist

Credits

- Text: JARD LEREBOURS