OLAFUR ELIASSON & KEVIN KELLY: Dream Boys

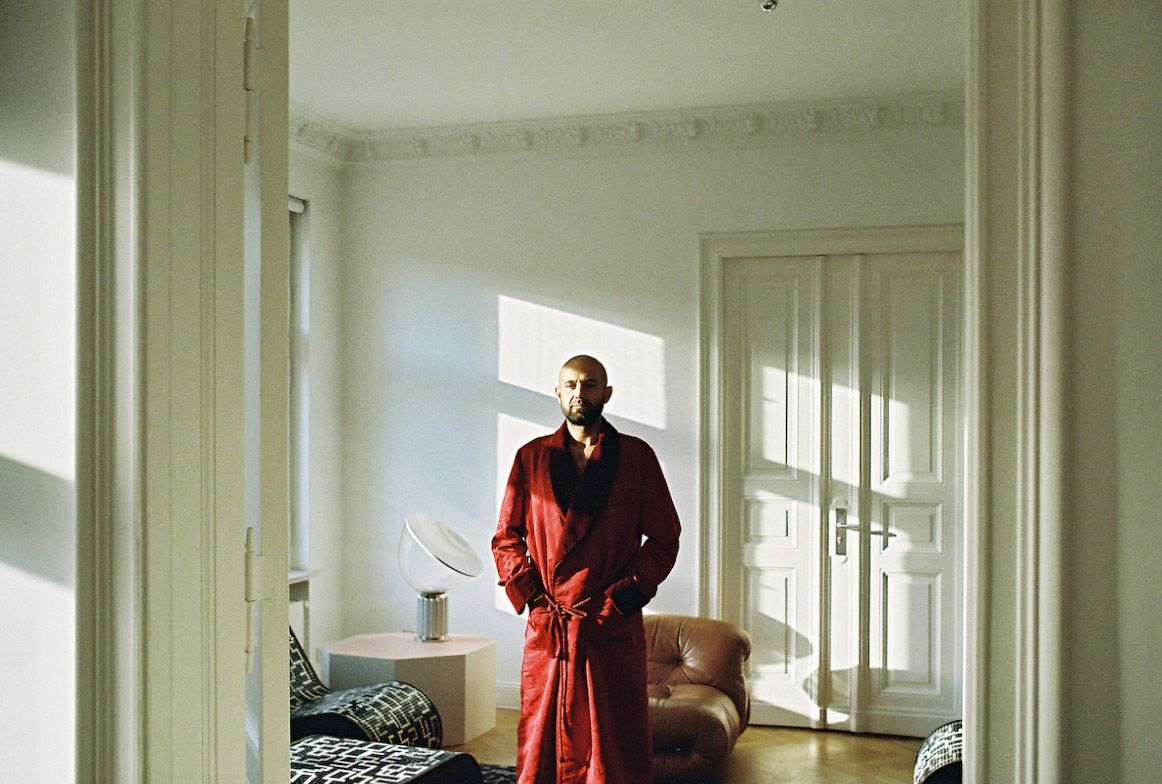

|OLAFUR ELIASSON

OLAFUR ELIASSON has been a long-time fan of KEVIN KELLY‘s writing, though the two had never met before they came together at the Digital Life Conference in Munich. Danish-Icelandic artist Eliasson, 44, is known for his large-scale installations that harness elemental materials such as light, water, and air temperature; Kelly, 58, is a former editor and publisher of the hugely influential Whole Earth Catalog and the founding executive editor of Wired magazine. He has also written extensively on technology’s impact on culture and society – his 1994 Out of Control: The New Biology of Machines, Social Systems, and the Economic World cemented him as a veritable “oracle” of Techno-utopianism. Eliasson’s glasses magnify his eyes a bit, lending an air of heightened awareness to his steady, measured calm. Kelly, backpack in hand, ruddy, gives off the impression that he’s slightly unaware of what’s going on – that is, until he speaks. This conversation occurred about a week before the revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt, and only months before the disastrous fallout from the earthquake off the coast of Japan. Their call for an articulation of empathy, synchronicity, action, and love on a global scale seems more urgent than ever.

Kevin Kelly: One of the things I really enjoy about your work is the way it veers very close to science and technology. I don’t know if you think of it in that way. Does what we call science play a role in your work?

Olafur Eliasson: If we’re talking about science as a vehicle for readdressing the structure of society, in a broader sense, then yes. I am not a scientist, and the truth is I don’t know much about science. Yet I do find the systematic way in which science, in the last 10 or 20 years, has seemed to address the nature of the viewer rather than the nature of seeing highly inspiring. Science seems to be reconsidering its own methodological foundations. It’s in your writings, for instance. If anything, I’m critical of the traditional understanding of science that society in general operates with. That’s why I’m constantly considering the way science produces reality. I look at the way science is communicated, because in a way the communication of science has become its co-producer.

I call myself a science groupie, because I like to hang around scientists. I’m not a scientist either, but it provides an approach to the world I find very useful. It’s an inquiry; it’s about testing things. What’s interesting is that the scientific method itself has changed so much in the last 200 years, and the things we think of as the essence of science – the double blind experiment, the placebo – are very recent inventions. That means that in the next 100 years science will change even more. The scientific method itself is changing. I think the things that artists do can influence the trajectory of the scientific method’s development. The very method that has come to define what we think of as scientific is itself being influenced by the rest of culture.

Yes. That’s why I find it strange that science is constantly separated from societal concerns by politicians. Scientific knowledge and facts are kept from being enacted if they don’t bring in votes. Artists can disseminate knowledge that is externalized by politics. This is generalizing a bit, but I think that art can, to some extent, allow different types of language to enter the realm of political reality.

One of the things science is about is teaching us how to change our minds. I’m really curious about what you have changed your mind about, say, in the last five years. Tim Leary used to say, “You’re only as young as the last time you changed your mind.”

I agree. In the last five years, I’ve become increasingly interested in the extent to which artworks are reality producers. As an artist, the challenge is to create a sense of plurality, collectivity, or togetherness based on the singular experience – on singularity. When you look at a work of art, you simultaneously evaluate the nature of the experience you are having, who you are, and what the art is about. This already produces a context of collectivity. But the context of collectivity, as you have made it very clear to us, has been highly co-produced by means of shared communication.

And that’s changing.

It’s changing faster than I can finish this sentence. You have talked about this for a long time. What I’m interested in is the psycho-social, or psycho-emotional consequences of our being so incredibly well connected.

One of the most fundamental things these rapid changes are affecting is our very identity as human beings. Almost every day there’s some new technology – whether it is genetic engineering, a robot, or even the discovery of higher intelligence in animals – that forces us to reconsider what it means to be human. We thought we were the only ones who could do things and now suddenly we’re being told, oh no a robot can do that, or AI, or new genes can be engineered. So, almost daily we have to redefine who we are. The social aspect of communication today is playing a similar role, because the boundary between “we” and “you and me” is shifting, which also impinges on the idea of who I am. I think it’s a psycho-social identity crisis that we’re going to be in for the next several years. We thought we knew who we were, we thought we knew what a human was, and now we don’t. It changes every day, and even if our definition of ourselves doesn’t change tomorrow, we’ve still lost that certainty, or footing we used to have.

“The Internet and the interconnectedness it offers is something that everybody is still completely puzzled by. We’re operating at quickened speeds, but we haven’t yet learned how to feel on the Internet. Only when we succeed in learning how to feel online can we move to the stage where we’re truly expressing ourselves.”

Where does that leave our sense of responsibility?

I think it undermines it. We felt a stronger sense of responsibility in the past, but as I argue in my new book, we’re developing a new sense of collective agency. The entire system we’ve made is pushing back and this exerted force is making us realize that our actions are not autonomous.

In your book, you talk about conviviality, about a notion of interdependence instead of autonomy. I’m thinking about this a lot in my work – we are all so connected, and clearly this gives us a sense of interdependence, but it’s an interdependence that mostly performs in a weak way, that has very little of what you might call synchronicity. The little bit of synchronicity that exists is what keeps the connections alive – but it’s reduced to an “I-can-see-when-you-are-online” kind of thing. I’m just wondering what the next step will be in terms of empathy, responsibility, compassion, and so on. I’m not a skeptic; I do think that we have it in us somehow.

I’m very optimistic in general, as you know. I think there is moral progress. We are expanding our circle of empathy over time – from our immediate family, to the clan, and larger, to the nation. We’ve also increased it across races, slowly but not completely. The next step, which is starting to happen, is perceiving that we have some empathy with other species. Regarding animal rights, some people think it is wrong to even own a pet. I think there is a general expansion now, and it wouldn’t surprise me if in a thousand years people start talking about robot rights and having empathy for things that we’ve built, and that we can’t unplug them.

Cloud computer rights.

Exactly – we’ll ask if we’re allowed to unplug it. It may be very weak still, and it may diminish the strong ties we’ve traditionally had with our families, but there is an incipient outward expansion of empathy.

I’m probably asking questions with an outmoded language or worldview – questions that belong to a period that is over – but I’m pretty captivated by the fact that a single communication system, like Facebook, can engage 500 million people.

Like a country.

Yes, well it’s almost 10% of the Earth’s population. People on Facebook are to some extent connected, which in a way makes the six-degrees-of-separation idea obsolete. We are beyond that. So, how does causality travel within that system? What is the emotional measure? I’m not criticizing it for lack of content. But one can hope a movement will come out of being connected in these uncontrollable ways.

A movement towards what? What movement do you hope for?

New kinds of criticality. By that I mean the heightened introspection that reflexivity allows for. As consumers we are prone to taking things in, rather than being critical of what is offered to us, since we have been brought up to do so. Maybe Facebook, this incredible system of interconnected diversity, could allow for new and different types of criticality – both internal and external to it. I say this because I think this is how art, essentially, progresses. It deals with this incredible situation where you are both involving yourself and involving yourself in the nature of involvement. Art, as a system, involves many critical agents, and they reach out and are entangled in the artwork. This is why I find art so exciting.

Something I’ve changed my mind about in the last five years is our ability to change. I think we are changing ourselves and I believe we’re much more mutable than I thought before. The dogma used to be that once cultural evolution came along, it would take all the pressure off biological evolution: our bodies would stop evolving and all the evolution would happen culturally. That turned out not to be true. It turned out that when culture came along, our bodies started evolving one hundred times faster than they did before. We know that our brains changed when we became literate. Our minds actually think differently. That means that if we spend eight hours a day sitting in front of a screen, it’s also going to change how our brains think, permanently. And I don’t mean through generations.

What do you think is the primary consequence of being in a system where everything and everyone is so connected?

My reading of the long-term history of technology suggests that diversity is increasing as a result. We have an incredible diversity of, say, five million different species, but they’re on a cell cycle that was standardized a billion years ago and is still running. Homogenization and standardization, on a very small protocol, allows for huge diversity. We’re seeing a little bit of that in the social communication world where we’ve gotten stuck with a few standards that started early on. And they’ll probably remain for a thousand years as long as they continue to work, but they can actually liberate diversity and expression because you’ve standardized on some elementary communication protocols. Some would argue that the opposite is true, that the more we’re communicating, the more we become homogenized. But in the end, difference – the delta variable – is what becomes most valuable. The difference is what powers things. You have to communicate enough so you can communicate the difference, but it’s the diversity that actually generates value.

But don’t you think the amount of fear and egocentrism that dominates large parts of the world essentially prevents this notion of diversity? I think people find shelter in sameness.

Yes, that’s a refuge. People like to believe that they like change, but in the end when you give them change they sometimes retreat. It is strange that people pay a lot of money to visit another place and then go and eat at a McDonald’s. They do seek something different, but I think they temper the strain of the difference by retreating to the same. But I’m actually worried about the case when we are all listening to the same music, watching the same movies and studying the same things in school – that kind of globalism. What is more worrisome: that we do understand each other, or that we don’t understand each other? We always talk about how some people in the world don’t have access to digital technology, but what happens when everyone in the world has it and we’re on 24 hours a day? That seems to me a much more interesting problem than the problem that some people have access and some don’t.

That’s why I’m asking for a transformative type of emotionalization – and not championing subtly esoteric, autonomous mental states.

If we had a connection to every living person on the planet and we could communicate in some way, it would change our notion of ourselves. A change could reverberate through the entire system. We haven’t seen that yet, but I think we’re going to see a moment when everyone on the planet actually responds to something. When I was growing up, there was the Woodstock event. The curious thing about Woodstock was that everyone who went there thought it was their own idea. They appeared there, and nobody knew that there were that many people coming. It was just like, oh my gosh, we all had the same idea at the same time. That was only 500,000 people or so, but imagine if you have 6 billion people who all think they have the same idea at the same time. I think it will be a very profound moment when the entire planet is responding to something or inventing something together. It will redefine us as individuals because we will realize more that we’re not really just individuals. That’s not evident to everybody, particularly to a lot of Americans who think of themselves as individualistic cowboy types, but I think there’s a shift already happening in America.

“We don’t even know what humans are, which is bad enough, but we have a bigger challenge ahead of us, which is not just about knowing who we are, but since we’re technologically remaking ourselves, we have to ask who we want to be.”

So what kind of event would it take to produce that great global “A-ha” moment of connectedness?

We’ll need a disaster. Or, it could be something wonderful, like what’s happening in Iran and Tunisia right now where they’re trying to use new media to make political changes. I always say that powerful forces, like powerful technologies, are not really powerful unless they can be powerfully abused. So we should expect that the kind of power that might be working towards a democratic change of a regime could also be subverted by that same power. I don’t think this new, growing technology-enabled connectedness is only going to produce good things. The global financial meltdown, for instance, showed us that our economies are certainly knitted together: I think it became clearer that everybody has to do well in order for me to do well.

The shift from being connected to being aware that you’re connected is a little like the shift from having a feeling to having what I call a “felt feeling.” What’s the difference between a feeling and a felt feeling? A feeling is still something you contain, but you might not quite know that you have it. It might result in stress, or nervousness, or laughter, or some seemingly unpredictable behavior. The felt feeling is when you suddenly become aware that you have a feeling. I know it sounds a little like meditation hour, therapy, or Buddhism, but bear with me. Feeling a feeling allows you to consider the resources in the feeling and how to use those resources as a kind of energy. This might be a spiritual energy, but it might also be political, or it may be both at the same time. The Internet and the interconnectedness it offers is something that everybody is still completely puzzled by. We’re operating at quickened speeds, but we haven’t yet learned how to feel on the Internet. Only when we succeed in learning how to feel online can we move to the stage where we’re truly expressing ourselves. This is where I think there is incredible potential for creativity in the way we are interconnected. That’s why earlier I brought up synchronicity, doing something together at the same time. It’s not exactly the same, but tribal chanting and dancing is a way of creating a sense of collectivity that understands the importance of synchronized action. I wonder how that can be translated into these new online situations, how we can make a system that facilitates the expression of singularity and emotion.

I see what you’re saying. We haven’t really been able to feel the change going on. There has been a lot of intellectualizing of digital media, but there is a lot of confusion about how we feel towards it. One of the things I’ve noticed among my friends is that they’re polling each other about their information media habits. They’re asking, “Do you use Facebook, are you twittering, do you still read newspapers, what are you doing?” Everyone is so unsure about what they’re doing and whether it’s working. So I think you’re right, the emotional stability, or foundation, is sort of not there yet, and as a result there’s uncertainty, maybe even anxiety over whether what each of us is doing is normal or good.

It leads to a lack of self-confidence.

One thing I think might help us feel is illustrated in a statement Brian Eno has made a couple of times. He said there wasn’t enough Africa in computation and computers. Computers stimulate mainly our heads and our finger-tips. When digital technology gets to the stage where we could hold, caress, or otherwise use our whole bodies to communicate online, I think we will have a basis for the emotional foundation we’re lacking now. Communicating with our whole bodies instead of thinking through our fingers gives us more entry into the emotional dimension.

I could not agree more. The thing is, when I talk about feelings it’s important not to interpret it in romanticizing terms. We live in a state of numbness: we lack self-confidence, we’re hyper-numb, and in the West, we are close to a sort of psycho-burnout. We are worn out, fatigued. In this state, sudden emotion could operate as a spark. I would never loosely use the word love, but I’m very happy saying it this way: we should allow love some space. Obviously, that’s what Woodstock was about, but now it’s patented and institutionalized. I’m looking for the felt feeling that can shed values without being dogmatic or normative. I think this is what art can be about.

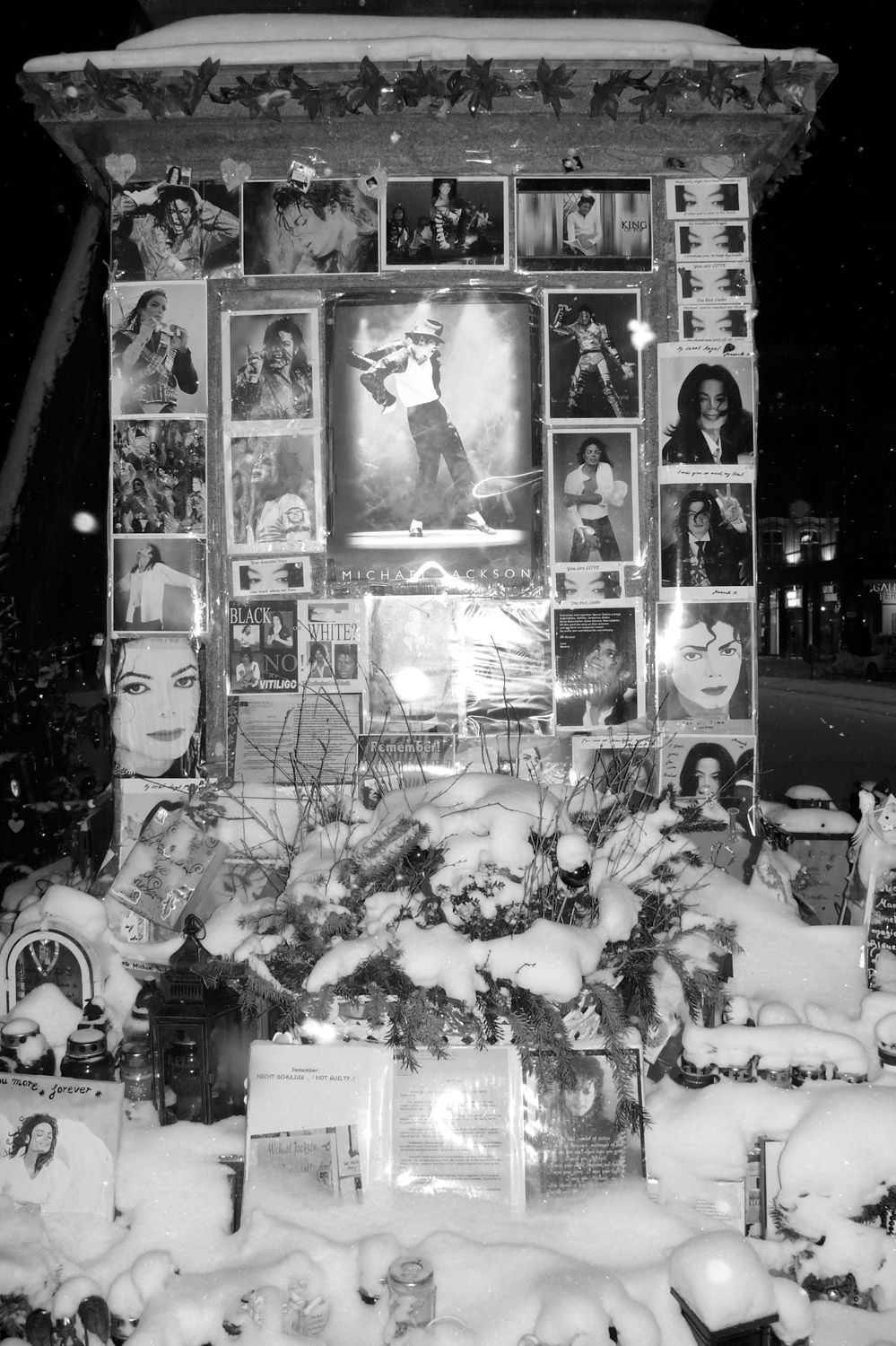

Did you see that shrine to Michael Jackson out in front of the Bayerischer Hof hotel?

No. There’s a shrine?

There’s a shrine to Michael Jackson and there were people, even just two days ago, adding things to it. It’s very bizarre because it’s got angels, cherubs and candles. It’s a very primitive kind of love, but there was something they were showing, and this was expressed all around the world when Michael Jackson died. I like the idea of visualizing global love. If we could use technology to promote love at the planetary level, what would that look like?

It would certainly not be prescriptive. It would not be a state of mind; it would be a sense. Just like we use our eyes and ears, we can use our sense of love. I think it sounds great the way you talk about planetary love. Speaking of Michael Jackson, after I scream at the people in my studio – which I almost never do – I always mention that I yelled at them with love, like Michael Jackson used to do. He always said this after screaming at his assistants.

That’s interesting. I think one component of love might be our ability to deeply share identity. When you love someone you’re sharing some kind of identification with him or her. You’re saying, “I know you, I see you, I recognize you, I acknowledge you.” Maybe for this planetary love it would be necessary for people to identify with others, strangers, at that level. That would be part of it. It could be brought on by a threat, or by having empathy for others because of their situation – I’m not sure what it would take. What’s interesting to me about digital technologies is that they allow us to have relationships in ways that were not possible before. One of those may be that planetary span. Another way of putting this is that I’m looking for other ways to love. There’s something beautiful about the way we can use these technologies to connect to people we don’t know but have some kind of working bond with. I would say that I connect with people I don’t know online daily. People write to me all the time and I have conversations with them, and some of them grow into people I eventually meet at a conference. Even purchasing something very expensive from a complete stranger on eBay shouldn’t be disregarded. Handing money over to a person you don’t know is quite an astounding act. We have a level of trust that wasn’t possible before. These things are small, but they add up over time to where we are exploring a new dimension. And in the long run, we will look at the time when we’re sitting in front of a screen as an anomaly, because I don’t think there’s any reason why digital technology has to be screen based. My idea of a highly evolved person is someone who doesn’t carry anything. I don’t want to carry anything. I want to be able to walk in and have the walls recognize me. I can pick up anything and it will know me and I can talk to it. Technology will just be all around us, integrated into our environment. Screens will be everywhere, so we won’t have to sit in front of them. I don’t think we need to have a digital world that is separate from a real world. We’ll embed it into the real world. That is one way we can restore physicality and physical emotion, that rootedness in our being that we lack. I’m hoping that will happen and it seems that’s the general drift. We had motors disappear, and I think we should have screens disappear, in a certain sense.

I agree. A more physically involved interface is necessary. Language has its rational relationship to reality, which makes it efficient for communicating, but communicating through speech or text represents a form of expression that does not involve our bodies. This means that sending a filmed message to a friend, for the time being, seems a more relevant message because everything from the tonality of the voice to the facial expressions allows for a diversity of resonances to operate. My facial expression carries much more information than a text will – at least a text by me. Of course this doesn’t necessarily make things easier.

Part of our difficulty with technology is the acceleration of its development. It makes it very hard to gain mastery of things. We all feel like newbies – once we master something it’s gone the next year. That does erode our self-confidence, both as individuals and as a collective. We don’t even know what humans are, which is bad enough, but we have a bigger challenge ahead of us, which is not just about knowing who we are, but since we’re technologically remaking ourselves, we have to ask who we want to be. That’s an even more difficult question.

“I always say that powerful forces, like powerful technologies, are not really powerful unless they can be powerfully abused.”

It requires a strong sense of responsibility and self-criticism.

Exactly. When you see humanity as being something mutable and changeable, it requires a certain maturity that we may not have right now to say, “Well, humans should be X,” or “Humans should be Z.” How do you even go about answering that question? It sounds cliché, but we actually need global solutions to things. It’s scary talking about doing anything globally, no matter what it is, even if it’s something that seems good. We’re still a little suspicious of doing anything at that level. It’s really kind of weird that we’ve lost some of our big dreams from the 1950s and 60s. What’s the biggest dream we have right now? Maybe it’s that we’ll connect everybody to everybody else, but that’s it. We’ve got one dream. After that, what’s the biggest dream?

Historically, we’ve burnt our fingers on a lot of utopian ideas. This has created a fear of global movements, yet I do think there is a possibility to fuel our sense of responsibility for global systems and still operate on a very singular level, so that we are both plural and singular at the same time. We should probably avoid polarizing the two.

What I’ve learned from it all is to believe in the impossible. Like with Wikipedia – I was a complete skeptic when it was beginning. I still don’t understand why it works, but it works. The fact that we have an encyclopedia that anybody can change and it is the most reliable, authoritative encyclopedia ever made makes me believe other things are possible that I don’t think are possible now. Today, Wikipedia is in some ways like the atom bomb was for my generation. It’s an icon, a mythic icon that you have to deal with. Every person of this new generation always has Wikipedia there to remind them, just like the atom bomb was there for us, that these forces can do things we didn’t think were possible. That’s what I’ve learned from these past ten years: to believe in the “impossible” things. I’m curious to know if you, as an artist, could solicit or propose a big dream. What would a big dream for us, the people alive on the planet today, be? How big of a dream should we have? Do you have a big dream that you would like us to have?

One dream I have is that collectivity no longer be based on grouping people who are roughly the same; real collectivity is a form of democracy based on successfully dealing with diversity.

So a big dream of yours would be to have a worldwide democracy?

Yes. Keeping in mind that the democracies we have now are not particularly democratic, that’s a pretty big dream right there. I’ve been invited to do a work of art for the 2012 Olympics in London, and I said I would like to make a work of art that consists of nothing but a feeling. You won’t get a sculpture, or a painting, or anything you can carry and show in a particular way. We need to find out how to communicate that, which is why I went back and looked at some of your talks again, TED talk that I like so much. I find the Olympics surprisingly unemotional, aside from the elitist, heroic moment, which is highly emotional. But for a global event about body, space, physicality, temporality, and synchronicity, the Olympics seem pretty stale to me. They have been detached from any sense of reality whatsoever. It is not a global event that has anything to do with the world, sadly. It is also highly commercial, of course. So one idea is to put a feeling into that non-emotional equation and see what will happen. What are your dreams?

Big dreams. Something to achieve, something to work towards would be a global governance of some sort; not a government, but some mechanism for dealing with global problems. That would be a tremendous achievement to work for. Another big dream would be to actually know all the other living things on this planet. We don’t know them. We haven’t made an inventory of all the species on this planet yet.

Like another book of life?

We haven’t made that yet. I want to make a web page for every species on the planet. Even to just know their names. We may only know about 5% of the species on this planet and it seems a shame to me that we haven’t done more to know about them.

That’s interesting because it raises the issue of categorization. Would you allow emotional behavior to add to the diversity of poison frogs? A happy frog and a sad frog, do they go in the same category?

I’m not even concerned about categorizing, I just want to meet them and say that we recognize that you are here. Another big dream would be to make a map of this planet accurate to one meter – that would be an incredible achievement. There are so many things we haven’t done yet – to have 100 % literacy, why not?

I’m glad to hear that global governance is one of your dreams. What if we consider it a sense? What do we have – 188 senses? I will dream tonight about your dreams.

I want you to dream your dreams, not my dreams.

Well, I do that too, every once in a while.

Credits

- Text: OLAFUR ELIASSON

- Photography: HADLEY HUDSON