“Yeah, Wellness!”: SHANTI DAS on Rap and Healing

|Jeffrey Martín

“The purpose is Silence the Shame, and the passion is music!” Shanti Das said in her Southern accent, which drips with the love and confidence of that auntie you at times like more than your biological mom. Despite being virtual Zoom worlds apart – we were separately sheltering in place at the time – speaking to her made me forget the screens which safely separated us.

Hired by LaFace Records as National Director of Promotions straight out of Syracuse University, Das came to hip hop at a very young age – and became an immediate player in disrupting its history. She played a critical role in shepherding OutKast into the spotlight and, in turn, bringing Atlanta into position as the center of Southern hip hop, and as a global influence in music, fashion, and beyond. Over the course of her career Das has worked with artists including TLC, Erykah Badu, Goodie Mob, Prince, Jermaine Dupri, and even Chloe and Halle – before Beyoncé collected them. But the marketing executive and author of The Hip-Hop Professional (2010), a guide for women seeking to make it in entertainment business, is not just invested in building successful careers in hip hop. She’s invested in the well-being of the artists and communities who create it.

In 2016, Das founded Silence the Shame, an Atlanta-based non-profit normalizing conversations on mental health and removing the stigma surrounding mental wellbeing. Social media campaigns with figures like Usher, Nick Cannon, and Ludacris made use of the network she built during her time as a music executive to launch a new movement. After getting 90 million impressions on her Instagram when her first Silence the Shame post went viral, she realized the need for these conversations was especially great in the industry she had been integral to. Four years later, with Billboard notoriety, a national program, and tours to better campaign to communities of color, Silence the Shame has grown to be a major player in the field of mental advocacy.

In the immediate background of our conversations over the last months was an industry bruised by canceled touring gigs, a 47.2 percent unemployment rate in the United States, spiking rates of Covid-19 infection in Georgia, and disagreement between Atlanta’s mayor and Georgia’s Governor over the best ways to approach the virus. Das, an Aquarius-Pisces cusp, brings those signs’ intentionality and emotional nuance to her work and to our conversation, which charts what’s changed since the 1995 Source Awards that canonized OutKast – in Atlanta, in hip hop, and in mental health discourse – and introduces us to her new brand, Yeah Wellness.

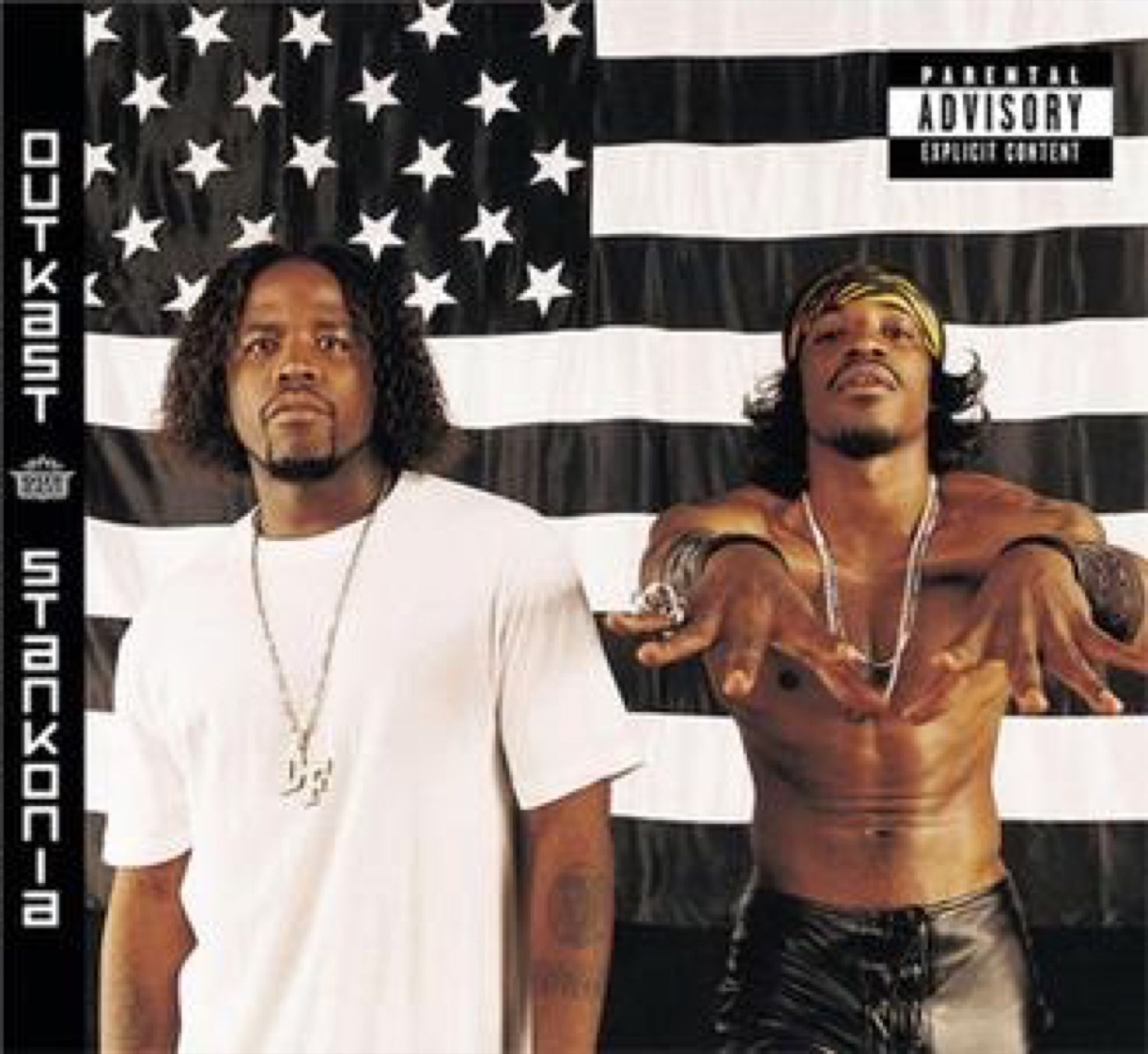

Jeffrey Martin: How was it helping raise André 3000 and Big Boi? I know you worked on OutKast’s first four albums: Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik (1994), ATLiens (1996), Aquemini (1998), and Stankonia (2000). You know I was in Atlanta, four years old, and knowing all the lyrics. We get it from the outside, but what was it like being in the space with them?

Shanti: I started working with OutKast in 1993 on their first record, “Player’s Ball.” We did a lot of promo dates, in and out of vans, through the Carolinas, New Orleans, Texas, flying out to the West Coast. And to be honest, they were like bratty kids I had to take care of! In the evening they would come and knock on my hotel door and I would be like: “What do you want? We need to get some rest before the show tomorrow.” They were teenagers, and it was a lot of fun. They were definitely unique. They were certainly brothers and they hung out quite a bit, but as they got to working on their second and third albums you could begin to see how they started to mature as individual artists with individual personalities. Dre was definitely more of the introvert, and Big Boi was the extrovert. We would always call them the Player and the Poet. Big Boi liked the cars, the bling and the chains, and he would rock his hats and jersey. Dre started to find his inner fashion and his identity there. How they came together as a power house was truly great to witness in real time.

Aquemini – the album name came from Aquarius and Gemini – I thought was brilliant and genius. Dre, as the Gemini, had a lot of different sides to him as a creative, and you didn’t know what side of him you were going to get creatively that day. Big Boi’s extroverted energy and specificity very much fit him as an Aquarius, and ultimately, that album. Myself and [LaFace Records’ Antonio] “L.A.” Reid were very keen to never control our artists, or do the “add water” technique of cultivating their career.

What is the “add water” technique?

Where you end up treating the artist like they are solely something commercial. Record companies do this because they know it will sell. L.A. and myself never did that with our artists. It was always about allowing them to have their voice in a creative way, and we always asked them to come with ideas for us to brainstorm and action together. They always brought ideas to the table. Dre brought drawing, and DL Warfield would enhance his art to form the packaging. That lady on the Aquemini album packaging – Dre drew that.

“Pun intended: we were the outcasts in the room.”

Did you get a chance to meet Janelle Monae? How has her work changed since you knew her?

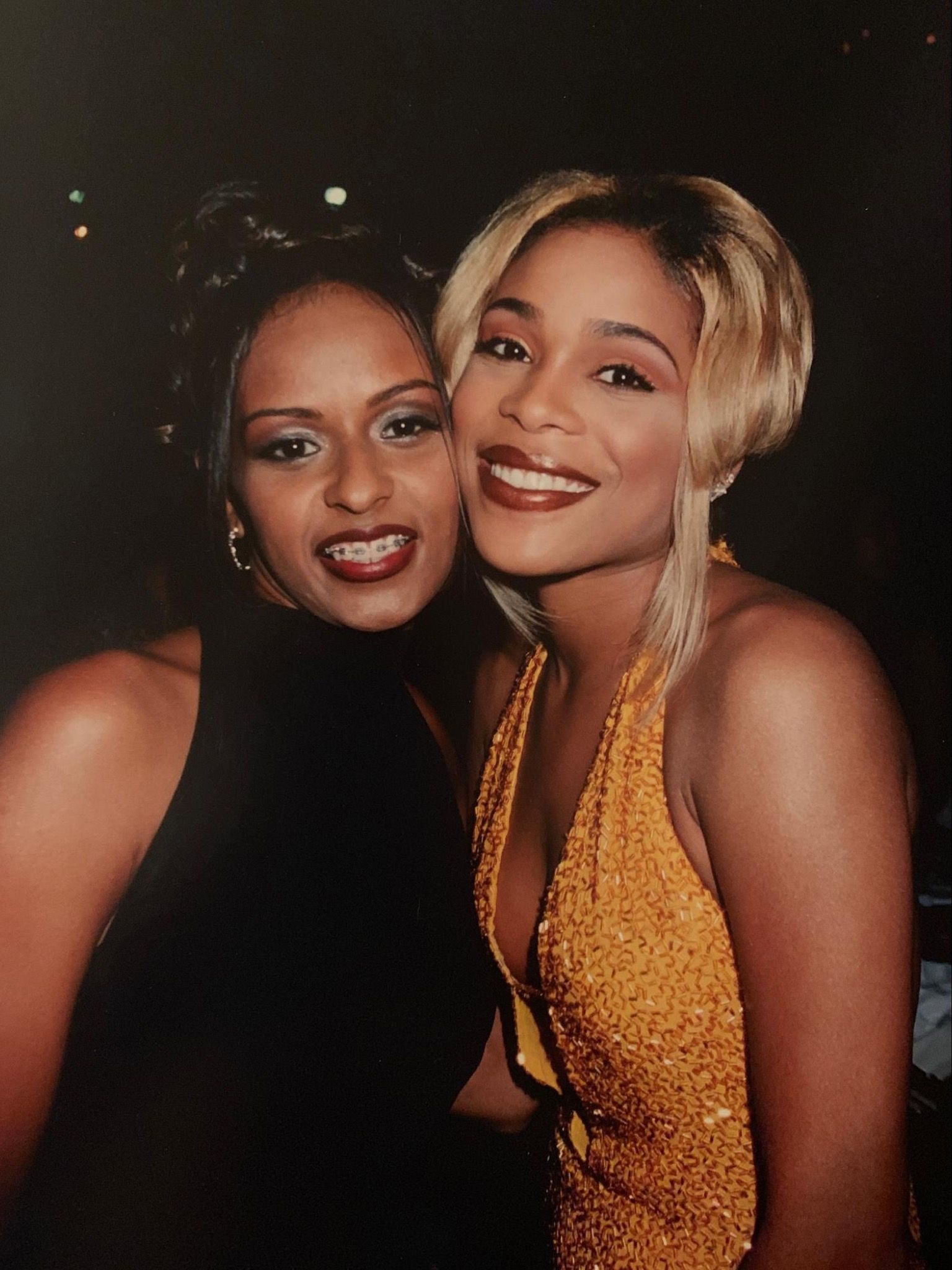

I remember when Big Boi signed her and did the collaboration with P. Diddy. In 2007 and she did a performance at my event RnB Live in New York – this was the hottest showcase for RnB music at the time. I have some amazing footage of her performance that I still have yet to release, because I was like “Who is this girl?” It wasn’t just a costume; it was her personality. She is very genuine as an artist, and everything from the fashion and the imagery is all her. Now she is a Cover Girl and a budding actress in addition to being a singer and songwriter. She is extremely unique and I am a huge fan.

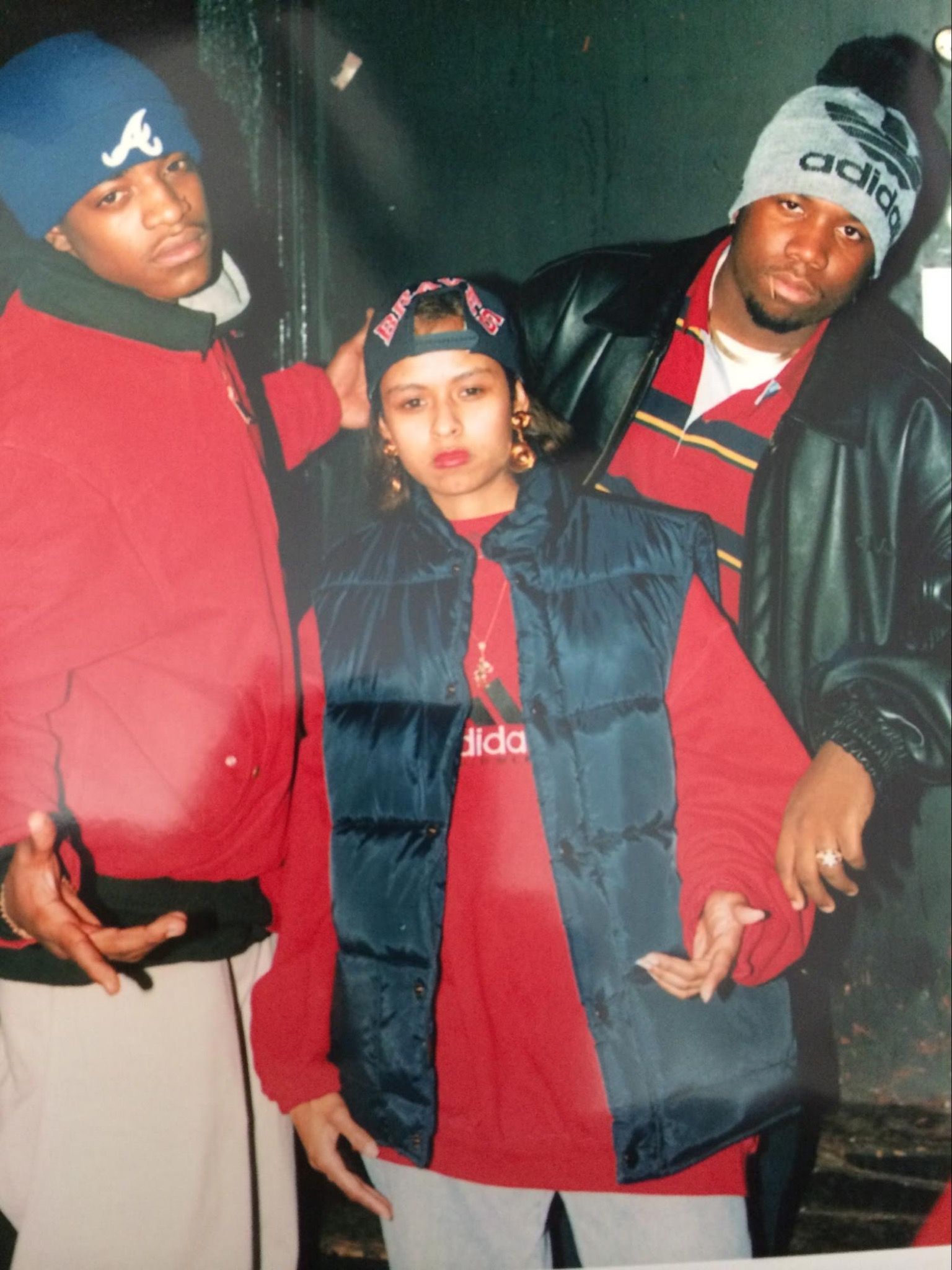

What was it like for you during the ’95 Source Awards before you all won?

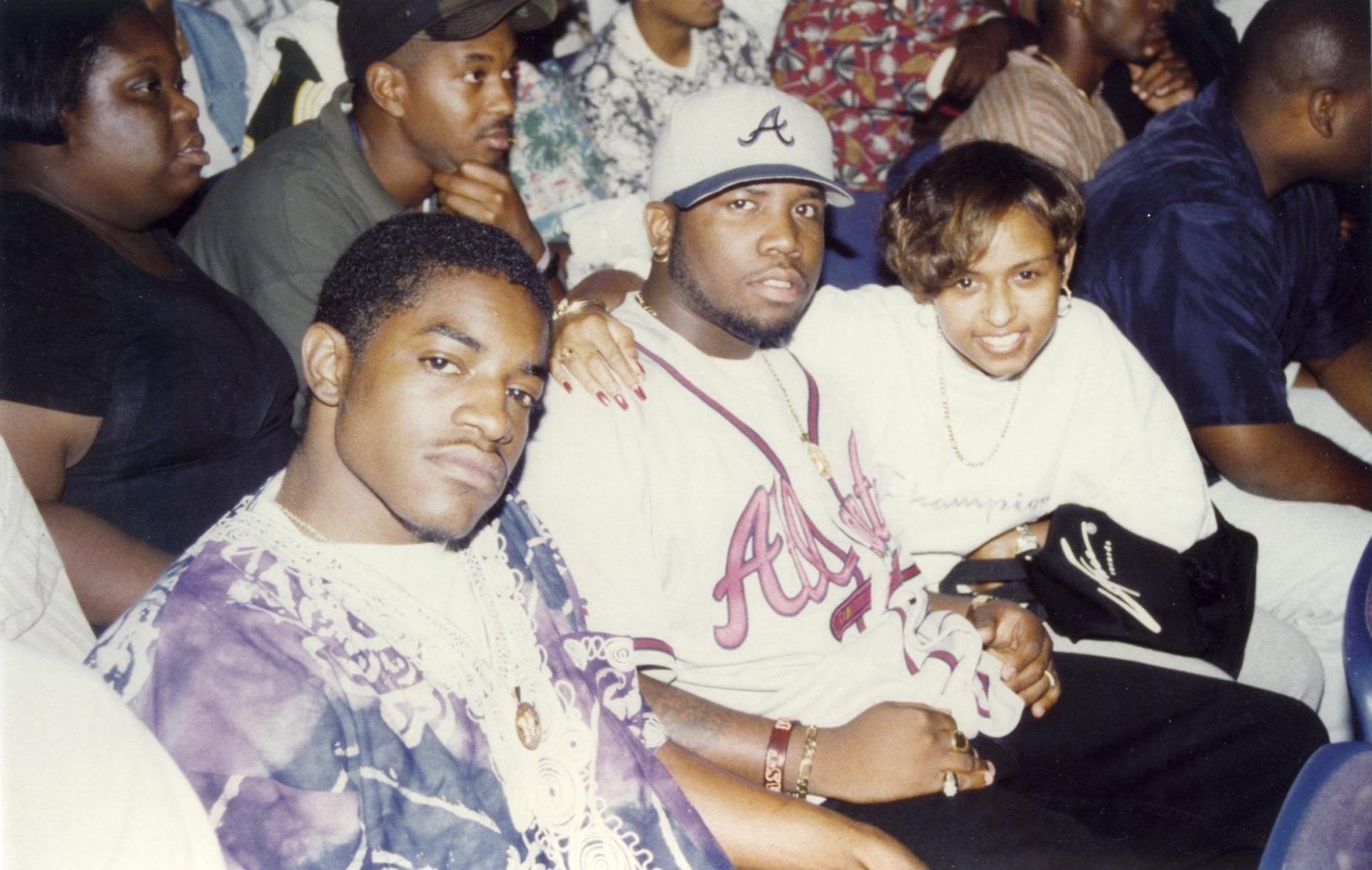

It is funny, their manager Blue Williams was there – shoutout to Blue! He just isn’t in that infamous photo that has been shared thousands of times. We were the stepchildren in the room. Pun intended: we were the outcasts in the room. We were from Atlanta and the city hadn’t popped off the way I felt it should have, as an Atlanta native living in New York City. Being from Atlanta, we always took pride in it, and we took pride in celebrating each coast. We celebrated the West Coast music, the East Coast music, and even the bass music from Miami, in the South. But in New York, it was New York, New York, New York.

It was such a weird vibe that evening during the Source Awards. It was energy, but I wouldn’t call it necessarily good energy because that was when the East Coast-West Coast beef was happening. So we were just sitting there observing, because that’s what we do, being from Atlanta. Back in the day, we weren’t so rah-rah, we were just taking it in. And then they announced the award and I was like, “Holy Crap – we won!” It was a “pinch me” moment. Like, “did they just call OutKast’s name?!” When people in the crowd started booing, I was like, “what’s going on?” I didn’t know if they were booing OutKast as much as they were booing that someone from New York didn’t win that night. I had a wide range of emotions. The guys went up, and then that famous moment that would go down in hip hop history happened, when Dre said, “the South got something to say.” I think he was happy, but frustrated at the boos that made him feel they didn’t think the South’s hip hop could stand up to the East or West coast’s. It was such a pivotal moment not just in Southern hip hop, but in hip hop overall. When I look back on it, it was such a special privilege to be there with them.

How did André 3000 and Erykah Badu impact each other as artists?

I remember when Seven was born, I went to a few birthday parties. I eventually worked with Erykah Badu at Universal Motown, but I always worked to not blur the lines between the personal and the professional with the artists I worked with. Looking at her creativity and his – they vibed. They both can be eccentrique at times; they both have some incredible imagery and thought. I think they complemented one another when they were together, and seeing them both now, they still have that.

“With the industry being so volatile, we need to be educated. I remember being in the industry, self-care and mental health were not things we talked about.”

Why is it important for those in the music industry to engage with Silence the Shame?

I am a product of the entertainment industry, so it is important for me that this industry understands things about mental health. We have seen artists in the past take their own lives due to depression or self medicating – we hear that in their lyrics. I think with the industry being so volatile, we need to be educated. I remember being in the industry, self-care and mental health were not things we talked about. It was always #TeamNoSleep.

Ungodly hours.

Yeah, and that’s not me knocking anyone who does that, but I look back at my life and career and I did not have healthy coping mechanisms back then. The industry needs to educate itself, to be able to better help the artists and their colleagues. Also, with what’s going on currently with Covid-19, there is a ton of uncertainty. Touring has been canceled and that is a main source of income and security for many artists – emerging or not. A lot of people are suffering. We don’t know if labels are going to have cut backs in the fall. Will they be able to take care of their households, pay their bills? When there is uncertainty, we are more prone to anxiety, depression, stress, and even suicidal ideation. As we continue to deal with these significant life events, I want for the community to be equipped to get the help they need, or have healthy coping mechanisms to process what we are dealing with.

“I know that I am the face of the organization, but what folks don’t get is that this is much bigger than me. I hope the organization can sustain long after I am gone.”

I remember your conversation with GHerbo on his PTSD diagnosis. He is a new artist and you were able to connect – the message is getting through. Silence The Shame is having an impact.

I have to give credit to Free the Vision, my co-host behind our Silence the Shame podcast, who connected with GHerbo’s his team. I had posted about his album back in February, and how he had called it PTSD. I was like, “who is this?” Once I heard the single, I felt it was so powerful and needed for this generation. I was excited. I got to kick it with him. He is extremely intelligent and very knowledgeable about what he needs to make it as an artist in this industry, and in life in general. Growing up in Chicago, in his neighborhood, he had to protect himself at all times. That is just the nature of his community. I never judged anyone who had to protect themselves in their neighborhoods. That isn’t my story, and I am just in awe of this man. I think he is an important voice for his generation as an African American man, in how he is approaching emotional vulnerability in his work. He has so many life gems, and his “you got to have a plan” quote ended up going viral on The Shade Room. I’m grateful they posted the clip.

How has doing this work with Silence the Shame changed you?

It has made me stronger and given me more confidence as a mental health advocate. I was afraid of expressing to people that I had experienced suicidal ideation, despite the “fame.” Whether it be our panels, podcast, or comments on social media that might hook folks – the work is moving the people and the culture in a new and more inclusive way. It has given me the confidence I truly needed to keep going.

I know I am the face of the organization, but what folks don’t get is that this is much bigger than me. I hope the organization can sustain long after I am gone.

What inspired the Yeah Wellness initiative? From my perspective on Instagram, the pandemic happened, and you were like, “we are doing Wellness Check-ins everyday at 3pm!” What came out of those conversations?

When COVID-19 first hit, all of my speaking tours were canceled, which was tough; running a nonprofit and losing additional income. I just sat still one day and was like, “Ok God, what can I do to move this needle forward, while also staying relevant with what is going?” I was literally writing notes and I said “Yeah … wellness!” Then I went on Instagram and started securing the hashtags, getting a website, phased out of my last bit of music exec work and put my marketing hat back on. I treated it like launching an album. Got the logo, got the handle, and then I thought, “hmmm I need a guest.” I texted Charlemagne about it and asked if he would be my first guest on Monday, and he said yes.

We went for about four weeks every single day, and now we are around once a week – to keep folks engaged. I am excited about Yeah Wellness being able to fund more of the work that Silence the Shame does. And there you go: a 24-hour marketing plan.

The Hip Hop music community truly loves you.

I am grateful for the community. To have Chuck-D do his first Instagram Live with me – it was like school was in session. He was talking about the foods we eat. D-Nice reached over 100,000 folks on Instagram Live. He had never even taken time to think of self-care, constantly being on flights and at events. This was an important conversation to have with him. I got the chance to interview Swiss Beats on all of his work with Versuz, and to talk with Common on National Silence the Shame Day. Common and I grew up in the industry, and having him bring up the impacts of incarceration was incredible.

“I want folks to be more patient with themselves and their loved ones around mental health, to practice self-care on a daily basis, and be there for one another.”

And what about your conversation with Atlanta native, Ludacris?

It was such a great convo. I have known him since he was Chris Lova Lova, and I was one of the first people wanting to sign him. He has such a respectable voice in the community – people listen to him when he speaks. Chris has really played a role in pushing the Atlanta culture. Pushing philanthropy is what he has been doing since the jump, and I have so much respect for him. He is so wise beyond his years.

Speaking of Atlanta folks, I’m trying to get Usher on soon. He was one of the first supporters of Silence the Shame. He is very dear to me, having been someone who looked out for me during a darker time.

Your work now is a testament to how you impact folks in the industry. How were you able to do this while grieving? The world is going to have to process grief on this level soon.

Being able to grieve with folks in this virtual way as we grieve loss of family, loss of jobs, loss of identity – this was something special that we were able to create, to humanize what we are going through during this pandemic. This was a safe and thoughtful space.

My purpose and passion are talking to each other. The purpose is Silence the Shame, and the passion is music. That is why the Billboard article meant so much to me. I have been trying to get industry coverage and to finally get it was amazing. Timing is everything. Those are my peers, and this is where I started. To not only be accepted, but respected in the industry, is something I am very grateful for.

What do you want people to remember from our conversation?

I want people to know it is ok not being ok, but what isn’t ok is not getting help for it. We all experience some level of anxiety and stress, whether you are on the frontlines, an artist, or an executive. We are all in the same storm, but not in the same boat. I want folks to be more patient with themselves and their loved ones around mental health, to practice self-care on a daily basis, and be there for one another. Hope is not canceled.

Credits

- Text: Jeffrey Martín