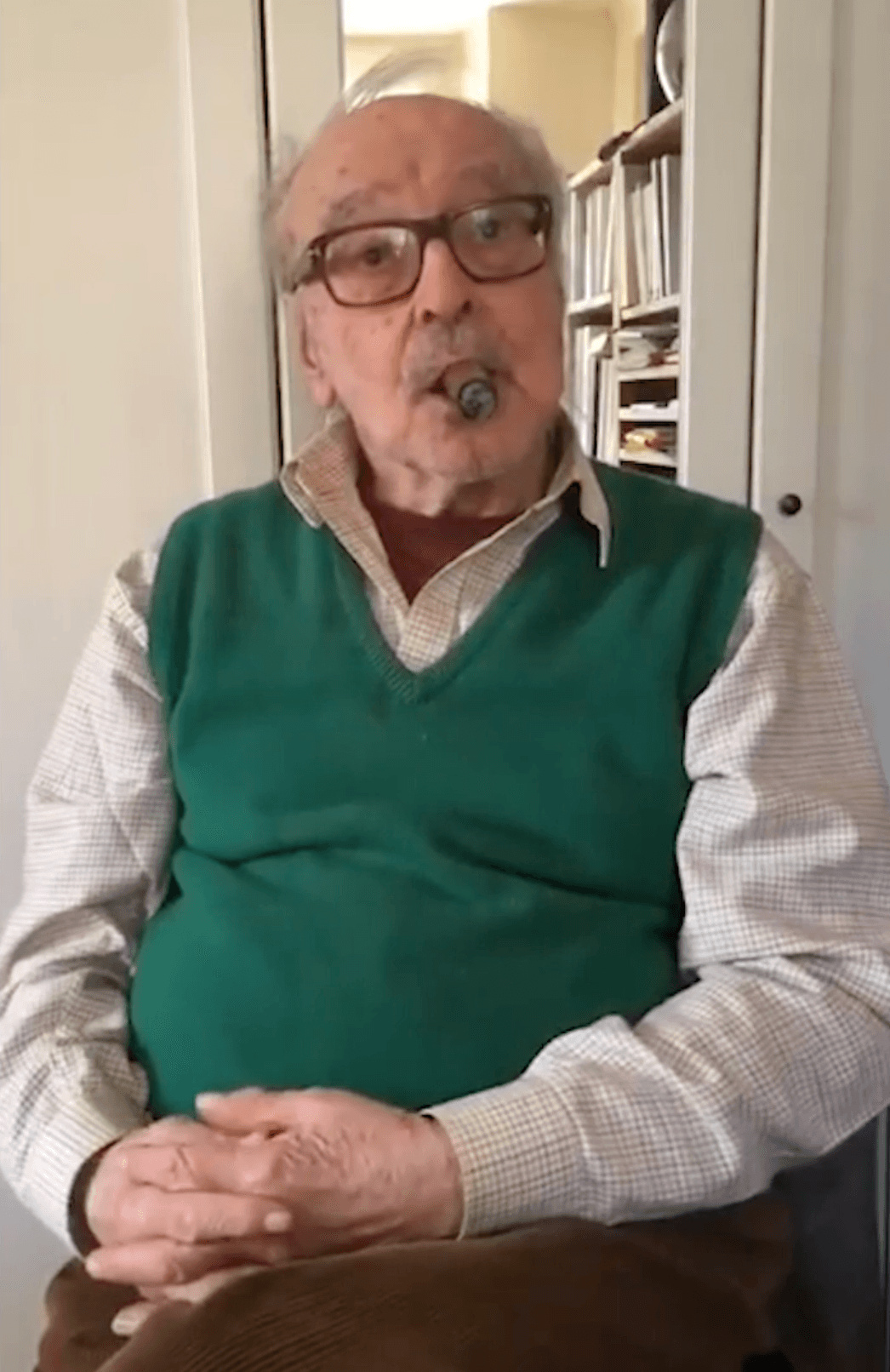

DEAR HELMUT BERGER (1944 - 2023)

“A loss as banal as this cannot rattle someone like Helmut Berger who, even dead, would cut an exquisite figure.”

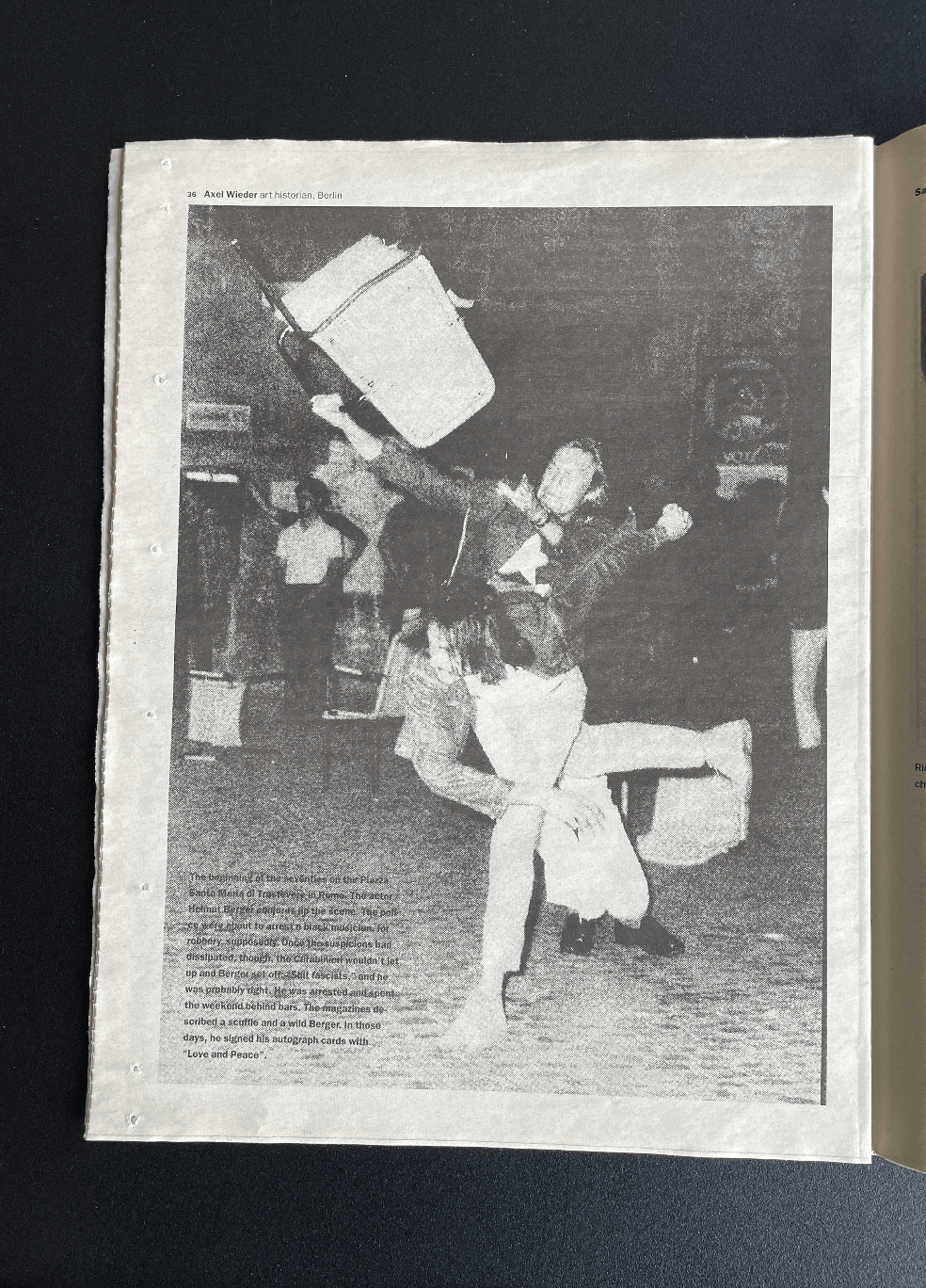

On the occasion of Austrian actor Helmut Berger's passing, we're publishing an archival article on him from 032c Issue #8 Winter 2004/2005.

In Salzburg, one occasionally catches a glimpse of a man in a trenchcoat strolling through the narrow streets and, at first glance, one would never suspect that he is one of the city’s most famous sons, second only to Mozart. The coat is too large and shows signs of wear and tear. The man wears a large pair of sunglasses. His eyes are lowered to the sidewalk. In the tobacco shop, he asks for a carton of “Marlboro Lights” and a carton of “Milde Sorte” which are now called “Meine Sorte.” “They’re for my mother,” the man says. “Give me six more of those lighters.” He points to a row of ugly but expensive lighters behind the saleslady. All in all, he lays around two hundred euros on the counter. But when the sales lady turns around to pick out the fine lighters, the man snaps up a plastic lighter from a plastic stand next to the cashier and tosses it into his plastic bag. On the way out, Helmut Berger takes a postcard. “Greetings from the City of Mozart!”

This shouldn’t be seen as an act of thievery. It’s more a flourish of childish flamboyance. Sometimes, at Meindl, he tries to smuggle a package of instant soup or a salmon fillet through the check-out line. If he’s caught, he smiles or pretends to be slightly confused but he’s always treated with the utmost respect. The fillet will be discretely extracted from his coat pocket and he will be politely dismissed. A Salzburger is a cultural person. One feels honored to have Helmut Berger slip out of the store with a little something.

At some point, the people of Salzburg will put up a plaque at the house of his mother in Aignerstrasse, and at some point, there will be a museum with Helmut Berger memorabilia. But for now, he’s still among them. And Salzburg and the great Helmut Berger will simply have to bear with each other. Faced with the current situation, both parties come off a bit like a married couple that goes through periods of not speaking with one another, though even the silences are celebrated in only the best salons.

Like the several expensive lighters and the one cheap one, it’s all a matter of give and take. Everyone who knows Helmut Berger knows: He has always, always, always given more than he’s taken.

It was here that his parents ran a humble pub after the war. His father, who died only a few years ago, was a prisoner of war and didn’t return until three years after the war was over. Helmut had to help serve beer. He left as soon as he could. In his autobiography (Ich, Ullstein, 1998), he wrote: “I’d had it up to here with the pub. With filling glasses and drunks. To hell with ‘Workers of the world, unite!’ The stench of mediocrity was all that arose from the masses. And I wasn’t part of it. A life with these people? Not me! I was the polite, obedient son of a polite, efficient, straight-laced father long enough. My gift to him was the hotel diploma which seemed to me merely a means to an end. In case I ran out of travel money or my mother’s checks wouldn’t be enough. Ciao, Father. Ciao, Salzburg. Ciao, Mother.” And now he’s back. Berger’s old landlord has shut him out of his legendary apartment on the Via Nemea in Rome. He’s living with his mother again. Instead of waking up with the Eternal City at his feet, he looks out every morning onto Salzburg’s main thoroughfare - towards Bad Reichenhall.

A loss as banal as this cannot rattle someone like Helmut Berger who, even dead, would cut an exquisite figure. The circumstances that cost him his apartment in 1992 were bad. A spark from an electric socket had set the apartment on fire. Paintings by Miró, Chagall and Schiele, a ceramic by Picasso, a collection of Jugendstil vases and furniture, countless letters and papers - all destroyed. Helmut Berger essentially lost everything he had back then that was of any value. “It’s better in life to get used to saying goodbye,” he wrote in his book; it’s one of those sentences that someone like Berger writes and, when spoken out loud, it takes on the aura of a sweeping entrance.

One can tell by looking at Berger that he doesn’t feel particularly well in Salzburg. He and the city - they bitch with each other a bit. But at the same time, he also knows: There are worse places to return to for a cultural monument. After all, here he’s pretty much given freedom to do as he pleases.

A clear flash of panic flickers through the eyes of the head of reception at the hotel Österreichischer Hof as Berger, his hair swirling, his eyes decisive, steps into the lobby on this fine day in May. Nevertheless, (or perhaps all the moreso), he’s served with extreme courtesy. In Salzburg, his regular appearances in the Golden Hirsch, in the Bristol or in the Österreichischer Hof have become like the regular pilgrimages of Everyman. Heralds of the Apocalypse are tolerated in this city. It’s a matter of tradition. To have Japanese tourists thrown off by the appearance of this man, or even a bit afraid of him, is simply a price the hotel director knows must be paid. Even Archduke Karl of Austria, who stands in the lobby in his traditional attire chatting with someone, doesn’t raise an eyebrow as Helmut Berger glides by him, gesturing obscenely. Now we can begin with our lunch, which the management of the Österreichischer Hof has wisely situated in a separate corner of the Wintergarten. Berger is still on top of his repertoire of gestures and he’s at his most charming when- as often happens - he suddenly tires of a topic and puts on an air of spectacular exhaustion. Among these is a mere lift of the finger before he looks one in the eyes and sweeps the forefinger like a windshield wiper. If that doesn’t work, he’ll lean over as he talks and let his face fall into his food before he lifts his head again with bits of grilled lobster on his pashmina scarf.

Only a few statements taken from this stressful yet also wonderful lunch must be half-remembered for the sake of history. Helmut Berger, the symbolic figure of bisexual promiscuity, who wrote in his autobiography just six years ago that he preferred sexual relations with men because what’s involved is “pure desire and direct sex, without any cuddling before or after,” now says, droopily, pouring a bit of vinaigrette over his lobster, “You know, sex without love is...Pah! ... C’est rrrien! Forget it!”

In his book, he complains of having suffered under Catholic sexual morality because he was plagued by guilt after every single sexual thought. Today, he says, “These feelings of guilt that I fought so tediously... Those, my dear, those were the whisperings of my angel! But unfortunately, the demon was far too often stronger.” At some point, he no longer heard the voice of his angel. On top of that, it was getting harder and harder to be more excessive than everyone else. When all of Roman society took to cocaine in the 70s and vacuumed it up their noses behind this or that corner, Berger, in order to make all the others look boring, had no choice but to consume tons of the stuff in broad daylight. He had Bulgari make him a small straw out of gold which he then wore on a chain around his neck. He also constantly wore the golden razor blade on his person.

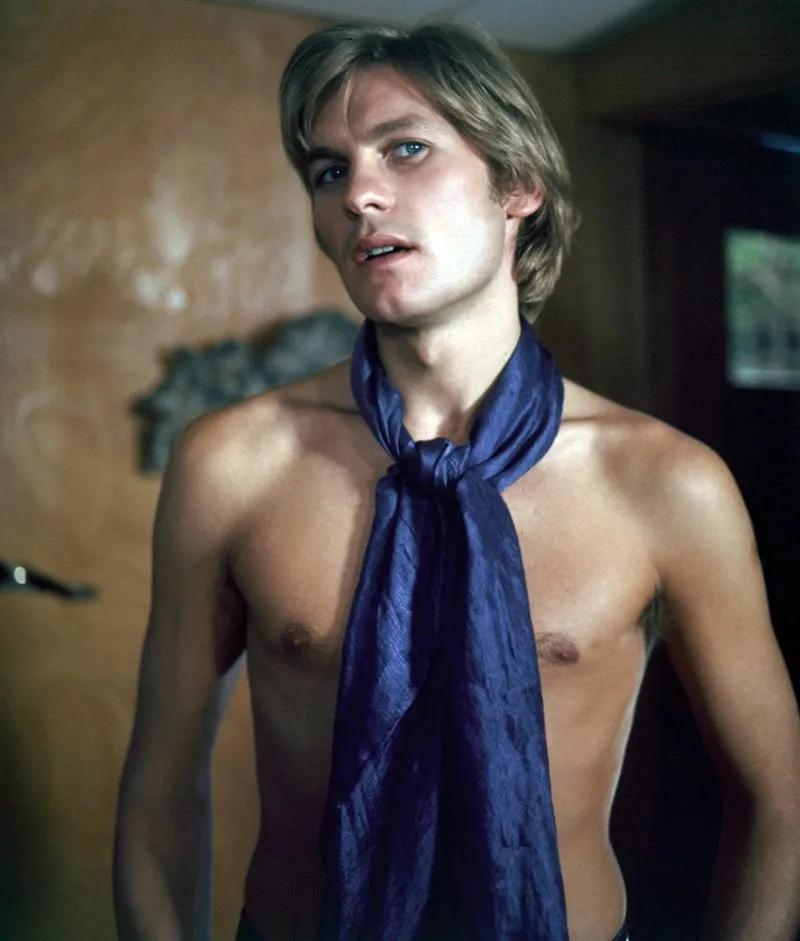

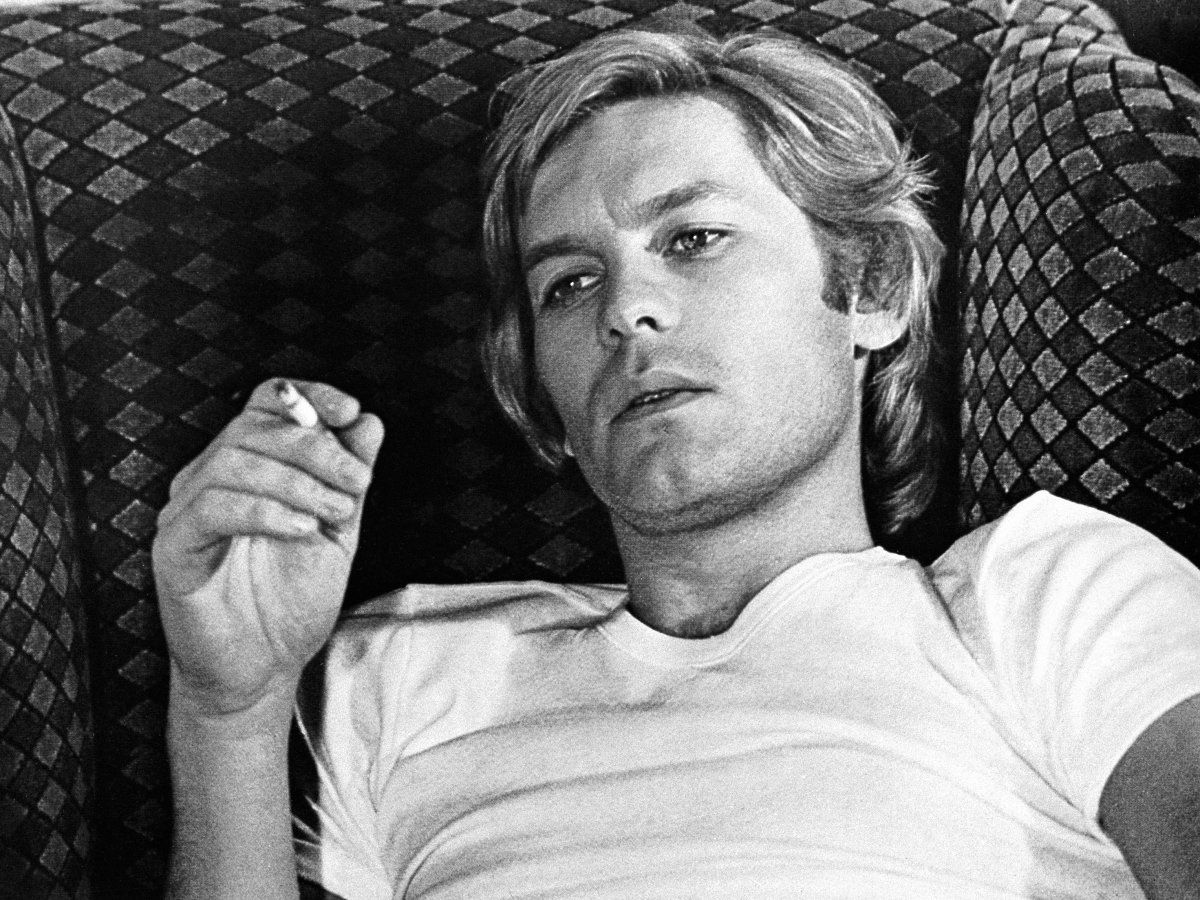

The great roles - and one must say, they truly were great roles - were by that time behind him: The young heir Martin von Essenbeck in Luchino Visconti’s The Damned, the consumptive brother Dominique in Vittorio de Sica’s The Garden of the Finzi-Continis, and then, Ludwig II. On his 30th birthday, Helmut Berger was the most sought-after young actor of his time, and not only was he young and extraordinarily beautiful, he was also a uniquely gifted actor. It’s possible that all that taken together was simply too much. Is there nothing left for a true genius to do at some point other than to play himself from then on?

When Visconti died in 1976, Helmut Berger chose the role that he has, in a sense, been playing ever since: The widower who’s lost his mind. But also one who, even in moments of excess, maintains at least a modicum of poise. At the Grimaldis Rose Ball in Monte Carlo, he was once so coked up that he lost control over his peristalsis and soiled the back of his white tuxedo to such a degree that he remained seated, not moving a millimeter, until the festivities were over at five in the morning. Or there was Princess Serra di Casano’s party at her chalet in Gstaad.

Whoever found Berger’s constant attempts to move in on this or that person somehow ill-mannered simply didn’t recognize that anyone under the age of 30 would have to look like Quasimodo in order not to be desired by Helmut Berger. Today, the mere thought of a party for his 60th birthday is, for him, an insult. “After the parties I’ve been to, it’s all downhill. I’ve had all the parties. Paris, Madrid, Monte Carlo, New York, Rome, Milan.” The way he pronounces this string of city names, it sounds like they’re all one long brilliant name for a single city. His friend Holde Heuer offered to organize a party in Munich. His reply: “In Munich? A party? Get me a bucket! Disgusting!”

But he does like to be reminded of earlier birthday parties. His 30th, for example, the “Bad Taste Party,” for which he invited to the nightclub Jackie O. All of Rome made the pilgrimage to that party. The Borgheses, the Niarchos, his friends Romy Schneider and Brit Ekland. Or his 50th birthday! At the Countess D’Estenville’s house in Rome. In some ways, that party was the late finale of the 80s, a pinnacle of liberation but also a hefty final chord of downfall. Many who partied back then in the salons of this baroque Roman palace are now no longer living or have slipped off the social radar.

Never again would so much cocaine, caviar and champagne be consumed as on that evening in the Countess D’Estenville’s abode. Even so, among the survivors of that evening are Jack Nicholson, Roman Polanski and, in his way, Helmut Berger. Today, fishing homeopathic drops for his circulation from a coat pocket, he says, “Drugs are the devil’s work! Drugs transformed me into the opposite of who I am!”

There’s a screenplay tucked under Helmut Berger’s arm. It was sent to him by a famous English director. With a pleading letter. Like the ones he’s always getting. Please, won’t he just take this one tiny role? He’s been carrying this screenplay and the letter around with him for days. His role would be that of a ghost who appears and reappears to the hero of the film, Alexander the Great, whispering messages. “You know you will kill your father. Don’t you, boy?” is one of the sentences he’s marked in yellow. The pay he’s being offered is evidently phenomenal. But Helmut Berger thinks the screenplay is simply awful. “I’m not doing the film. Je ne veux pas. Basta! I will tell them ce soir. Fuck ‘em!” He doesn’t know how long he’ll stay in Salzburg. He’s no longer prepared to pay the exorbitant rents in Rome. He was in Hamburg recently as a guest on Reinhold Beckmann’s talk show. The two of them had a conversation that was one of television’s golden hours because they took time for each other and Berger didn’t have to perform but was allowed to simply tell stories. He was embraceable. In preparation, Beckmann’s crew had seen to everything. Round-the-clock care, including a pedicure, manicure, massage - as well as a ravaging of the menu at the Four Seasons. “Hamburg,” Berger says suddenly after one of his long pauses. “I liked Hamburg. I could live t here.” Why not Berlin?“ Ugh! You must be joking! Proletarian town!” Shh! Hamburg, he says again, Hamburg is much more to his own taste. It was there that they finally managed to get him to Beckmann’s studio. Before then, Helmut Berger hadn’t left his suite for four days.

Credits

- Text:: Alexander von Schönburg

Related Content

HANS HOLLEIN: The Showroom Master

COLLIER SCHORR in conversation with THOMAS DEMAND

Inside RISIKO Issue 2: A Fanzine about KRAUTROCK

NEUE DEUTSCHE WELLE: Langston Uibel x Kwam.e

JONAS LINDSTROEM Uploads Our Fantasies in the Film TRUTH OR DARE

SURREALISM’S NOT DEAD: Master Filmmaker JAN ŠVANKMAJER

DEAR JEAN-LUC GODARD

Engage or Die: Actor CLEMENS SCHICK on Politics and FASSBINDER’s Legacy