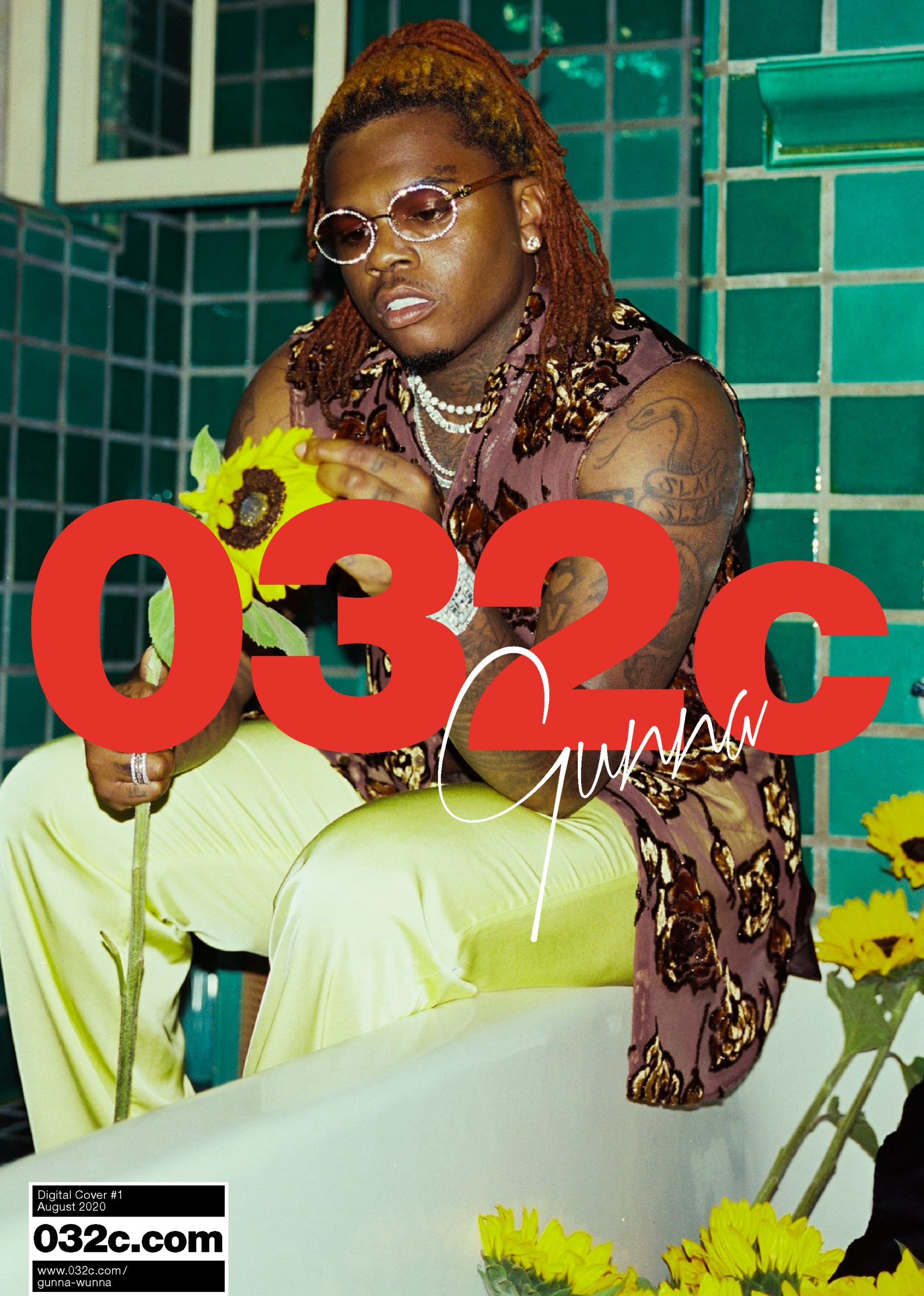

NEUE DEUTSCHE WELLE: Langston Uibel x Kwam.e

|Octavia Bürgel

Actor Langston Uibel and musician Kwam.e arrived at the 032c Workshop in the late afternoon on a sunny day this spring, fresh from a morning photoshoot at Berlin’s Haus Am Waldsee with photographer Christian Werner. While stylist Fiyori Ghebreweldi draped the rising stars in designer garms – from Margiela to Missoni, Burberry to Tom Ford, Ralph Lauren to Adidas and of course 032cReadytowear, available from Zalando’s designer edit – the pair had a moment to get comfortable before we spoke. By the time they left our offices, the impression was that they had known each other for years.

The Internet, with its accelerated stream of impulses and influences, has compartmentalized many young creatives – especially of color – into fragmented aspects of their identities. “The first…” and “the youngest…,” are superlatives we have come to expect as saleable nuggets of political signaling, applied increasingly in the wake of the last year’s global anti-racist uprisings. But these generalizations flatten talent and blur the message, contributing to a discourse that is more commercial than it is critical. Navigating the entertainment industry comes with its share of challenges and concerns, but in Germany, where Uibel and Kwam.e have begun their careers, Black individuals are near invisible – an issue of cultural representation that is the manifestation of a larger systematic problem.

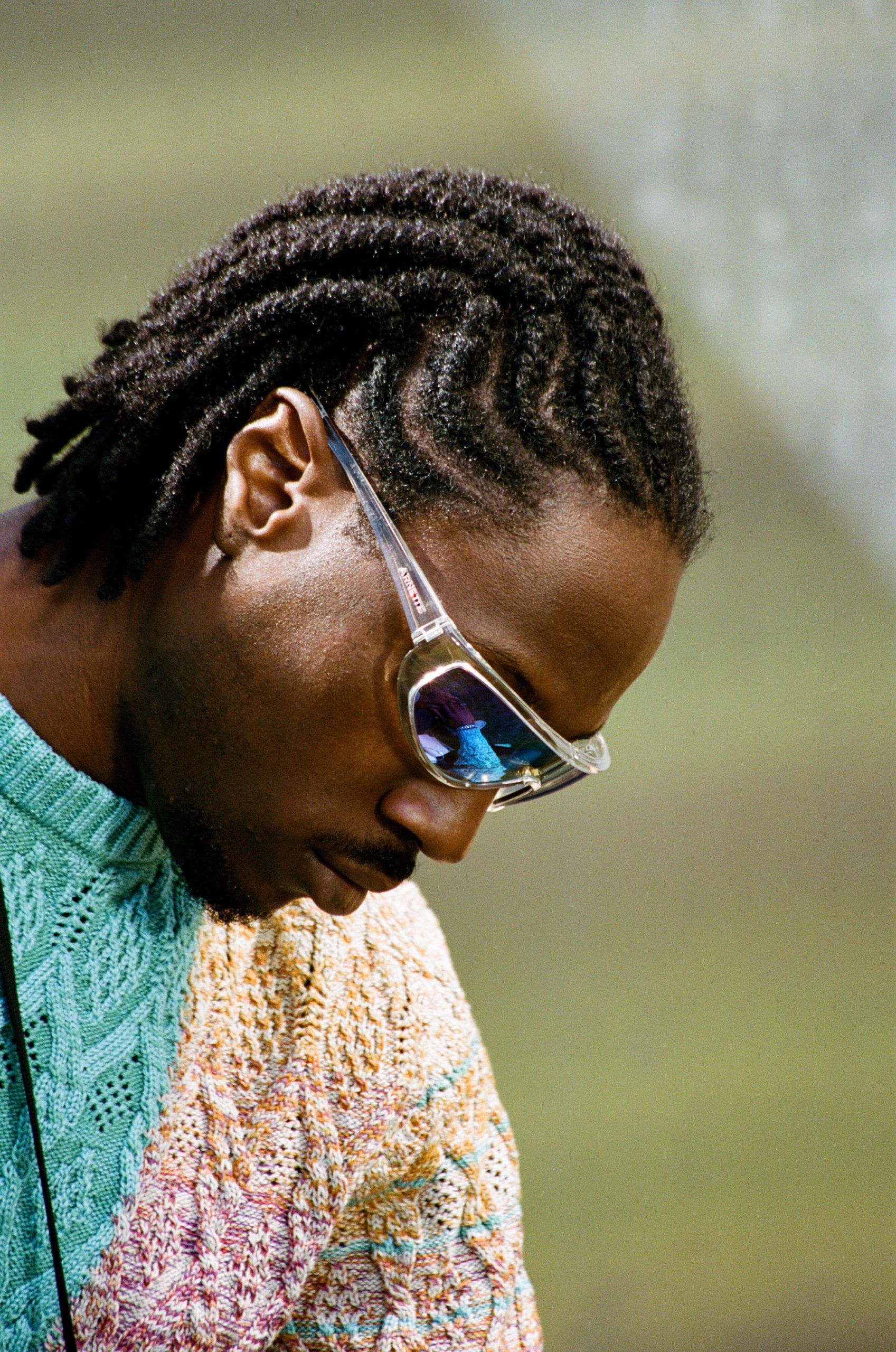

Kwam.e’s authenticity, enthusiasm, and passion for music are palpable the moment we sat down, transcending our intermittent alternations between German and English. When he first began rapping at age 13, it was at his older brother’s encouragement. “He taught me that when I spit something, it has to be real,” he tells us over coffee in the Workshop’s front office. Raised in Hamburg by a Ghanaian family – Germany is home to Europe’s second-largest Ghanaian population after the UK – Kwam.e says he loves living in Germany, “but of course there are social things that need to be addressed.”

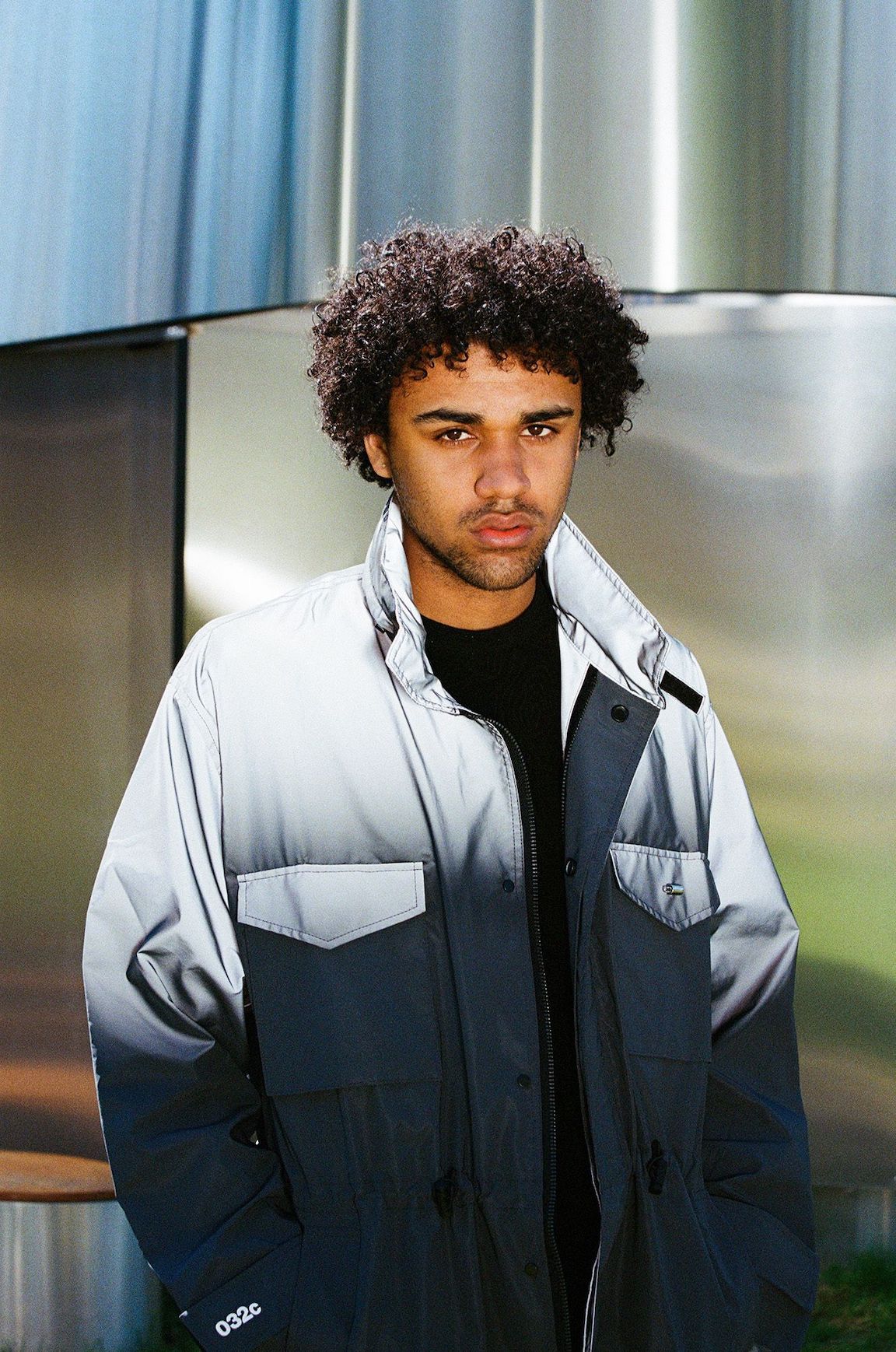

Born in London to a German mother and a Jamaican father, Uibel has lived in Berlin since he was eight years old. He started acting as a child, too, though “it’s really only been in the last year that I’ve accepted it as my job,” he says, candidly. His role as Axmed in Netflix’s 2020 mini-drama Unorthodox – his first time working in English and with an American co-production team – brought new opportunities his way, including work in the UK. This summer, Uibel will appear on season three of German-language Netflix comedy, How To Sell Drugs Online (Fast). Choosing to invest in German cultural production despite opportunity elsewhere, both entertainers are agents of change and hope for new generations of Germans.

Octavia Bürgel: It’s great to have you both together at the Workshop. Kwam.e, could you tell me a little bit about how you came to make music, and Langston, how you came to acting? Was there a specific moment where it clicked for you that this was what you wanted to do?

LU: I grew up around a lot of performers. My dad has a jazz bar, and a lot of authors and poets would come around – Benjamin Zephaniah and Bernardine Evaristo, people like that. It was a coincidence that I actually became acquainted with film, though. I was 10, and I was asked to participate in a short film made for the film festival here in Berlin. I did another film in year 10 of school, and after that I decided that as soon as I finished high school I would try to pursue being an actor. Luckily, I’ve been able to participate in really nice projects and films. How was it for you, Kwam.e? Did you just begin writing lyrics all of a sudden?

K: It took off for me when I was 13. We always listened to music in my family – James Brown, and stuff from the 1970s. I wrote all my lyrics down on a piece of paper, then performed it for my brother – he had always said that I should try making my own music. He told me what was alright, or what I should add in – he’s always reminded me to make sure that everything I’m saying is the truth. I rewrote the lyrics, and he was like, “Bro, that shit is dope! … You’re dead talented! … What else you got?” At that moment, I thought, “I can do this.” Just like that. Who is going to stop me? I’ve just been writing ever since.

Langston, in the past you and I have spoken a lot about your love of politics. I think you could draw a parallel between how you intersect acting and politics, and how Kwam.e combines lyrics and music to circulate a political message. Would you say that you put a lot of thought into the political implications of the roles you choose?

LU: It’s funny – actors tend to get into politics, or they want to have a say in the general debates that are going on in the world. I don’t believe that this is a given, or subsequently always fruitful. It’s one of the reasons that I didn’t study acting: I just wanted to keep working so that I would have the time to be able to read and study on the side – to be able to delve into politics on my own time. I think it’s quite difficult to say that film or art in general has to educate or be a vector to politics. But there are some extreme imbalances with respect to Black actors and Black artists, which makes it hard to withdraw from that. Early on, I decided that I’d rather play fewer roles than play roles that I’m uncomfortable with, which was definitely taking a risk since I’m so young. I know it’s a privilege to be able to say that I don’t need to earn that much money, since I don’t have a family that I need to put food on the table for. In the end, though, staying true to myself has really paid off. I don’t want to play parts that are blatantly stereotypical. There have definitely been a few shows that I participated in that were quite political, and that’s why I’m looking forward to the new show I’m in, How To Sell Drugs Online (Fast), which is an easy comedy. It’s a shame that as a Black artist you have to be so much more aware.

Working in German, you don’t have as wide of a reach as you do in English. How do you navigate that quite specific context, while remaining authentic?

LU: I don’t know how it is for you, Kwam.e, but I feel like the celebrities or artists in Germany are always very, very similar. There is one aesthetic. It is so hard sometimes when you realize that there’s this one form of how––

K: How you can be, or how you can make it.

LU: Exactly. The type of popular music or popular film made in Germany has been a certain way for the last 20 or 25 years. But I definitely feel that Germany is starting to slowly open up to the world. There are so many different types of artists in London, or in New York, and I think people are starting to understand that – and also that there are different types of audiences in Germany, too. But, in the process, it has definitely been hard.

LU: I don’t want to behave like an actor just because I am one. I want to be how I want to be, to dress how I want and talk how I want. I always felt that in order to tell an honest story, you also have to participate in real life. I try to stay away from living in a German actor bubble, because that has nothing to do with real life. How can I come into a film and portray a role if I don’t have real, proper friends [outside of the industry]? I think it’s also a question of Geschmack [“taste”]. The German taste is very specific. I find it so glaring to hear what is actually on the radio charts here. It’s absurd. And there are also so many cool, young German artists who just want so much more out of the film and music businesses.

K: They want to see it a bit more refreshed, you know? Germans, die haben einen Stock im Arsch [“they have a stick up their asses”]. I’m just saying it like it is. If you look around, there’s generally no Black community here, no Black culture that you can identify with or for others to make themselves aware of what it’s like to grow up as a Black person here, you know?

LU: That is what we’re building right now. We are the first generation.

K: [White Germans] think that if you grow up here as a Black man, you’re like Tupac or 50 Cent, and that’s just not the case. That’s why they don’t have any connection to us. As long as that’s not there, they can’t identify with us. For example, when they see that I’m a rapper, they immediately think, “Oh, I have to compare it to something. Let’s say Joey Badass because it fits,” and then they call me a “German Joey Badass,” but it’s not like that at all. I am fucking Kwam.e.

“I decided that my career is going to be a mixture of trying to break down walls here, and also recognizing that there are other industries out there, too.”

LU: You wouldn’t say that to a white artist, either. Like, “You remind me of Eminem,” or something. It’s a very specific thing. Being a Black German ist einfach eine sehr spezifische Sache [“is simply a very specific thing”]. But it is also just a reality. I also have the feeling that – just in the last five years, as I have grown into an adult and built myself a safe environment – I [have come to] know who I am. Growing up, I always felt strange with adults. When my dad picked me up from school I worried that it was awkward, or noticed that my parents were somehow louder than others. And really that is the most beautiful attitude, something I would never want to change – but there was nobody there to tell you that it is okay or that it’s beautiful.

K: It’s slowly changing, partly through social media. Now you can fight back and say what’s really going on. But right now [brands and media are] only paying attention to racism. They should be more mindful of showing Germans how we live here – just like they did with East Germans and [should with immigrant communities], whether they’re Arabic, Turkish, Moroccan. There’s so much culture to see, but you don’t see the Black people; we’re not represented at all in German culture. We’re just in the background. That’s why they confuse us with Americans or people from the UK.

LU: Yeah, they don’t understand that there are Black Germans who are exactly as German as they are, with a different skin tone.

I was raised in the States, but my father is German. I never knew anybody else when I was growing up – in America or in Germany – who was Black and German. I know, Langston, that you were very vocal during the protests in Berlin last summer. Do you think they helped crack open some of these conversations in Germany, or changed the discourse here at all?

LU: I grew up around my father, who is very political. Without him, I definitely wouldn’t have survived growing up in general. I wouldn’t have had the same sense of my Black identity – of knowing what is right from what is wrong. When that conversation came up here in Germany, it was such a weird feeling. If you had conversations about race before last summer, people would just dismiss what you were saying. Using the word “racism” would just make people angry. They would say things like, “That only exists in America.”

I spoke at the first protest last summer, and I realized that I was pretty overwhelmed. Suddenly, people – particularly non-Black people – were talking about the things I had been talking about all my life. I felt quite insecure about placing what I had been thinking about in their hands, because it’s so dangerous when non-Black people start to reassure other non-Black people that change is happening. It was a very weird thing to go from nobody ever believing what you were talking about to now, all of a sudden, everybody wanting to talk to you about racism. I am quite critical of how much structural change is actually happening. I’m aware that the situation has changed a lot for me: people are offering me different types of roles for work. But it’s not up to prominent people to decide if change is happening. We need the people at the bottom of the chain to get those jobs, too. How much effort are networks and production companies really putting into making change happen? I’m scared of the moment passing, of looking around and seeing that nothing is different. We have seen that before in history. We have seen these discussions in America; we have seen them in England. I’m always hopeful, I always tend to think about our community more than I do broader social change.

K: At any rate, racism is very much still present.

“If you look around, there’s generally no Black community here, no Black culture that you can identify with or for others to make themselves aware of what it’s like to grow up as a Black person here…”

Langston you spoke before about being taken as a spokesperson for the Black experience in Germany, but I want to talk a bit about celebrity more broadly. The American notion of “celebrity” is, I think, very much on steroids. What do you think about that notion of fame? Do you see that over-sensationalized ideal coming into German culture?

K: I don’t see myself as a rapper, I’m just me doing music. As for America, they are the stars. That’s where everything comes from – music, hip hop. If you make it there, then you have really made it.

LU: Would you ever want to go over there?

K: Yeah, safe. I was in Texas for the first time last year. I went to Houston for South by Southwest together with Ace Tee. We performed a couple of shows. I felt really cool there. Germany is late – later than Ghana. “Bist du Down,” the track I did with Ace Tee – as soon as it blew up in America, Germans thought, “That’s a hit.” I find it so sad that Germany is like that. That’s why I’d rather be like, “I’m just doing my thing, connecting with other people through the ‘Gram.”

What has it been like to come to prominence in the age of the Internet?

K: Through Instagram I could connect with lots of different artists, even artists from the UK who had heard my songs. I thought to myself, “Dude, I live here in Hamburg and all of a sudden I’m getting messages from Backroad Gee.” He’s a newcomer on the UK scene who I really support – I love his sound. He wrote to me like, “Hey bro, let’s link up when I’m in Berlin.” I was like, “Bro, safe!” I realized that I don’t have to be number one in Germany in order to be recognized by people from different walks of life.

LU: There is so much more out there – in the UK, in the US, where they are way more open and invite you to participate. You don’t have the same boundaries that you have here. I decided that my career is going to be a mixture of trying to break down walls here, and also recognizing that there are other industries out there, too. If you’re not going to have me at the table, I’m not going to fight for the rest of my life for a seat.

K: Everything has advantages and disadvantages. The main thing is just that people hear your songs somehow, and that at some point you can make music with them. Then you’ll have what you always wanted. I have a few listeners now who are also slowly checking my style. I used to do more boom-bap songs, and now for example I’m doing more trap style songs. The new fans that listen to my old songs are like, “What’s up?” And I’m like, “Listen, listen!” I can do everything.

When “Bist du Down” dropped, I was studying in the States and everybody was sending it to me like “Yo, they’re rapping in German!” It truly had such an impact. I’m assuming you didn’t set out to make a hit song when you recorded that, so how did it come about?

K: No, not at all. Tee called me, she was like, “Hey I’m at home – come over, I have a hook.” She sang me the song and it sounded really dope. We made the track and she had the whole vision in her head of how the video should look. She wanted it to be kind of in the style of the 1990s. I love that look too, and I always want to represent it in a German type of way. At the beginning, not everything was delivered as planned – there were supposed to be more people in the video. There were supposed to be more freaky girls. But we did what we did and got the best out of it.

You have to imagine that, from zero to a hundred – boom, we went straight to the top. All these people from Universal and various labels wrote us saying that we have to plan a tour out of nothing. We were at Frauenfeld [a music festival in Switzerland], and I had no plan whatsoever. There were all these big groups that we used to see on TV – 187 Strassenbande, Ufo361 – and we got to know each other. That’s when I realized how this whole rap game works. Our manager said, “You have to deliver properly now, you have to be better than all of them.” That was a big ass challenge. I thought “Ok, if this is my competition, I want to do the best I can. I want to show them what it’s like growing up Black in Germany.” We tore it down, and since then we have had a huge audience of listeners in Switzerland. I went home, and my manager called me saying “Hey, you’re going on tour with Future next year.” I said, “Which Future?” He said, “The musician.” I wasn’t listening to that much trap at the time. I did some Googling. I thought to myself, “How can it be that we’re doing this and Germany is not reporting on us or even claiming us?” Black artists here – in acting or music – they want to keep us down but we’re stepping up. The day we recorded “Bist du Down,” everything just came together. At that moment I became very convinced of my musical style, my taste. It gave me so much confidence.

LU: There’s no more crucial point in a career than realizing that even if people aren’t celebrating me, I’m happy because I’m confident.

Have you had a similar moment in your career, Langston?

LU: It has definitely been a big year for me. I feel like I’ve arrived. The feedback that I got for Unorthodox was amazing, and it’s funny that the project had to soar around the world in order for me to get recognition in Germany. Working with Netflix definitely opened doors – if you’re producing a show that isn’t just airing in Germany but on a global platform like that, you’re going to have to have at least a little bit of diversity. In that sense, streaming platforms are influencing the German market content-wise, which is a good thing.

In the last year I’ve also decided that I’m happy with what I do, and that gave me the extra boost of self-confidence, which you really need in order to go further. When you realize that you have it, you also realize that that’s what you needed to see in other people when you were questioning yourself. That was an interesting moment, when I realized that confidence was all my younger self had been missing.

Credits

- Text: Octavia Bürgel

- Translation: Octavia Bürgel

- Photography: Christian Werner

- Fashion: Fiyori Ghebreweldi

- Sculpture: Barkow Leibinger

- Location: Haus am Waldsee