David Douard Turns YouTube Comments Into Poetry

|CLAIRE KORON ELAT

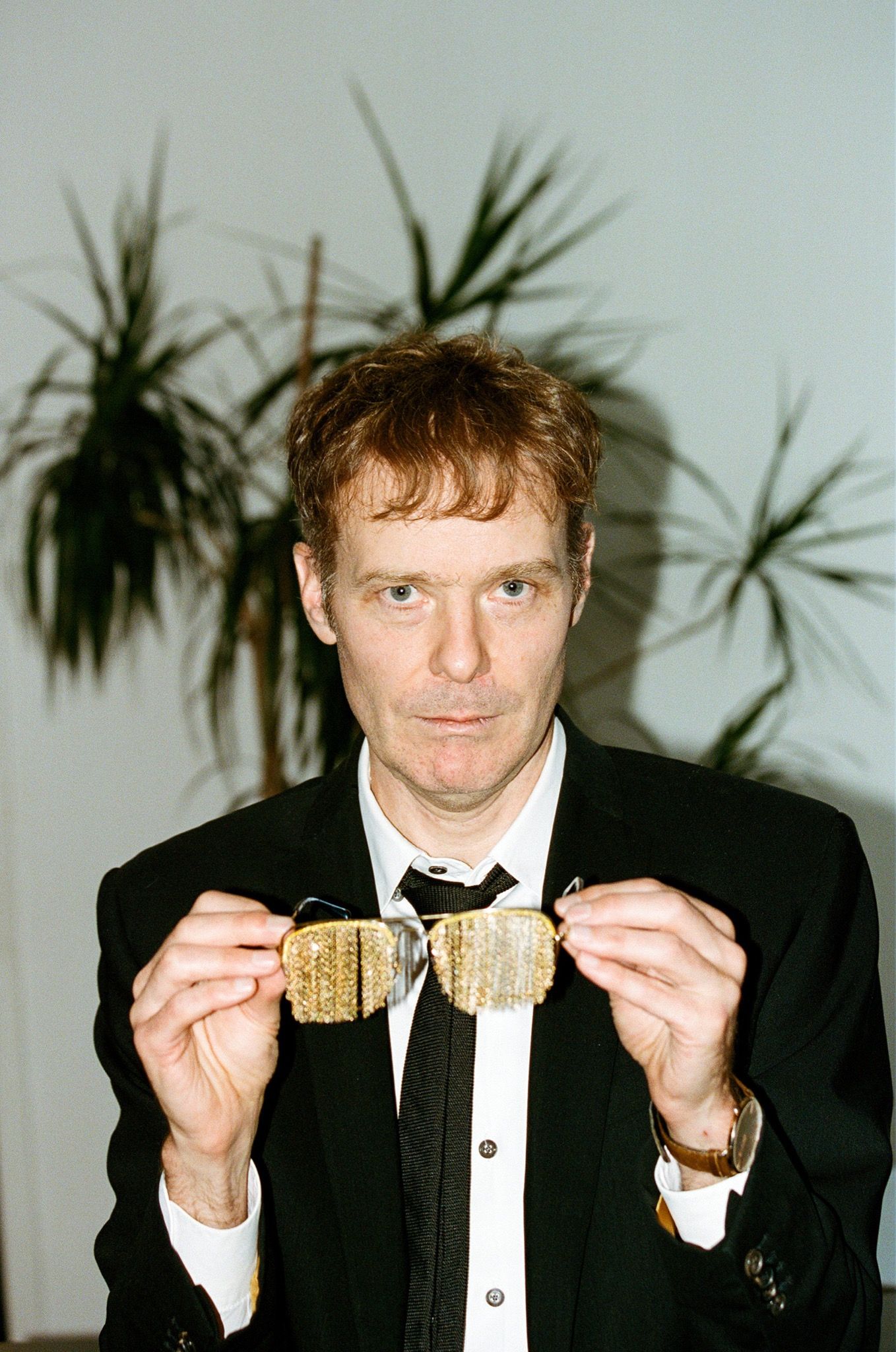

For artist David Douard, a seemingly profane YouTube comment can be turned into poetry that is then turned into a sculptural assemblage.

Referencing the history of science, technology, animism, and urban landscapes, Douard’s diverse interests are being reflected in his multi-medial, eclectic installations. In conversation with Claire Koron Elat, the artist talks about digging through the dark web, living in Paris’ suburbs, and the relationship between the private and domestic.

CLAIRE KORON ELAT: You often reference anonymous conversations, poems, and photos from the internet in your work, which serves as the basis for your sculptures and installations. I was wondering if you could describe this process, and how these poems become physically present in your sculptures.

DAVID DOUARD: The initial intent was to interact with people online, and to use this as the material for sculptures and installations. I decided to connect the materiality of sculpture with the digital content. It is interesting to keep the flow between these different elements, found objects, readymades, poetry, google images, sound pieces, and then make a collage out of it. It’s interesting to turn these elements into something physical and present them in a space. My work is a lot about contamination and corruption—that’s why it’s important that everything exists on the same level.

CKE: Who are you having these conversations with? Are there specific platforms or forums that you’re accessing?

DD: At the beginning, it was all anonymous. For example, I was looking at comments on YouTube. I think language is the most important authority in culture, so I find it interesting to attack it in some way, to chew on it.

I used to do graffiti in the streets, and it made me realize that the content of the sentences you’re spraying on walls is actually not that important. It’s important where you place it and how you do it, so it’s about conceptualizing the language on the walls. Changing a word is like working on society. This is what William S. Burroughs did when he was making cutups, he was acting on society. I think that graffiti is able to corrupt the city. It’s a form of resistance.

CKE: I also read that you’re specifically interested in the dark web.

DD: It’s been a long time since I last accessed it. I don’t go there anymore. But geek culture is interesting. I found it interesting to build my own computer and enter the dark web with this computer. But I’m not a specialist. I’m not interested in technology only. Sometimes it’s just a point of departure, a way to think about an object and make sculpture.

CKE: You’re also part of a generation that grew up with the internet. Do you feel like this is why it’s inevitable that you also include the internet and virtual spheres in your work?

DD: It’s interesting to be part of this generation, because we also lived during a time without the internet. I grew up in the south of France, and my father was a gardener. I kind of have the same interest in nature as I have in computers. I remember when I went online as a child and played some game or did research and then went outside to look at trees and flowers, I had the same emotions. This is why the physical and digital exist on the same level in my art. For me, everything is connected and there is no separation. It’s almost like technology is inside us, it’s an inherent part of our thinking. Perhaps that's why people think my work is post-apocalyptic or science fiction, but to me that’s not the case. I would say it’s more about the interstices.

Tetsumi Kudo’s work and the concept of mutation is very inspiring for me. I put a lot of things and objects together that should not be together. It all slowly melts and comes together as one block, which becomes the sculpture.

CKE: You were describing language as a tool for disruption. Do you feel like, when looking at your work, language needs to be added to it or that it needs to be contextualized through language?

DD: I like when language is something that goes into the work, gets corrupted again, and then goes out. But sometimes sculpture doesn’t need any words. When I work with language more directly, the text is almost like an ornament for the object. I like when there are incomplete words somehow present in a sculpture.

CKE: In your works, you also combine elements of the domestic with urban spaces. In what ways is the relationship between the domestic and the public also important for you? I was thinking about this question, especially when you were talking about living in Aubervilliers, which is quite stigmatized in Paris.

DD: You’re right. It is part of my experience that I lived there, and it was important be in a suburb that is so stigmatized by the media and society. The key point of my practice is taking spaces and making spaces your home.

CKE: The public and private are also quite political juxtapositions. In an art context, you can apply this to exhibiting in commercial galleries versus public institutions—both spaces have very different agendas.

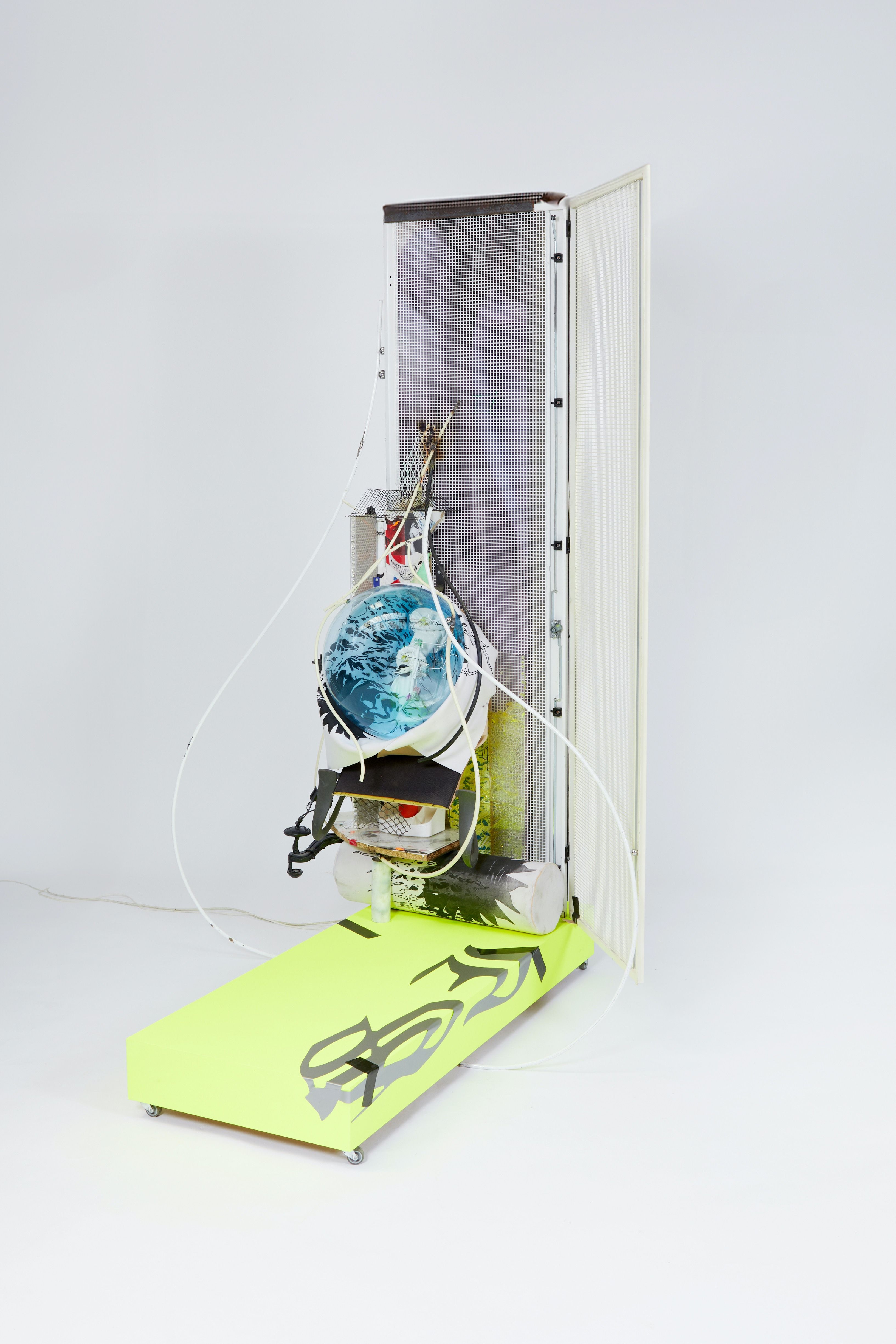

DD: I think when you’re making an object, you propose within your sculpture something that is hiding, something that’s not there. That is what I believe. There is a form of protection within the object, it can work in whatever the context is. For example, the sculpture UN’FOLD (2023), which I showed in a group show at Capitain Petzel consisted of a pedestal and a frame. I combined elements that have a certain authority in art, and then aim to corrupt them through a glass bowl, which is also part of the sculpture, and other objects that are more poetic. The duality between these elements give the work a kind of autonomy, even though there is an inherent contradiction. And it doesn’t matter where this work is shown—in a commercial gallery, an alternative space, or a public institution.

Credits

- Text: CLAIRE KORON ELAT

Related Content

Art World Resorts with Alex Flick

A Warning Against Popular Mysticism on the Internet, by ASHLEY D'ARCY

“Societies that are beholden to chronological time are immoral.” An interview with MARIA TUMARKIN

TOM McCARTHY Incarnate

Art World Resorts with Charlotte Diwan

The Story Behind the Monstrous Rihanna Sculpture at this Year’s Berlin Biennale

A Gateway to Forbidden Realms: Rob Kulísek

Art World Resorts: No Utopias, but Chicago