REM KOOLHAAS: Consistent Modesty and the Strelka Institute in Moscow

|Shumon Basar

While the architecture field has changed more in the last 30 years than in the previous 3,000—thanks to the rapid acceleration of globalization and the convulsions of the market economy—architectural education has mostly failed to keep pace. The STRELKA INSTITUTE, in Moscow, proposes a different way of looking at architecture: not only for the general improvement of design, but with the intention of introducing research as the most essential basis of architectural education. AMO is developing an educational program with Strelka to address a range of issues that are pertinent worldwide, and particularly urgent in Russia.

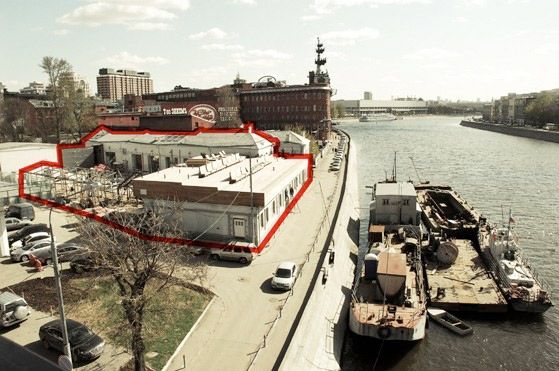

Strelka, a nonprofit and independent institute based in Moscow’s former Red October Chocolate Factory, brings together architects, intellectuals, designers,and media professionals in a relationship of creative interdisciplinarity. Each year, a select group of 30–40 students (all studying for free) will undertake pioneering and innovative research in order to generate a final “product”—a report, book, website, film, object, or something else entirely. With an ethos of “thinking and doing,” Strelka students will be tutored and guided by a network of prominent cultural figures selected and mobilized by AMO.

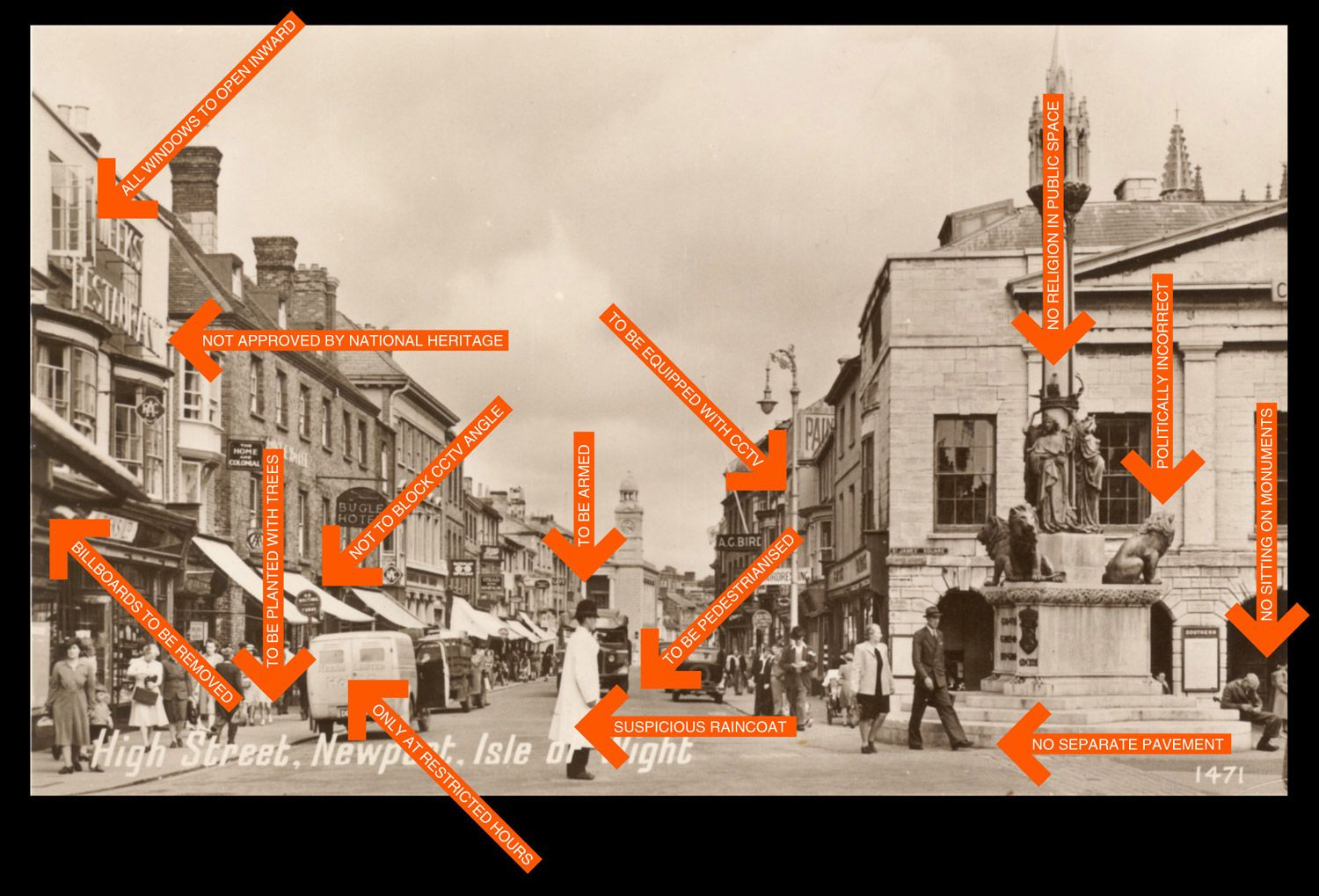

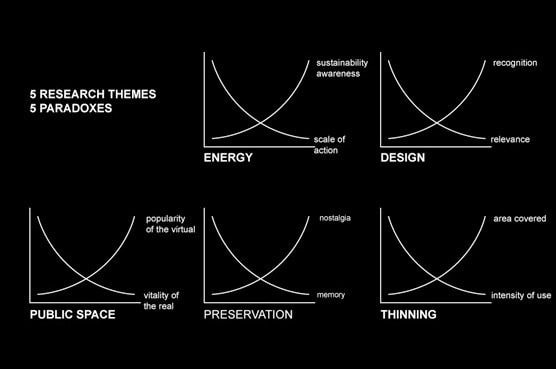

Students will focus on one of five topics developed by AMO: design, energy, preservation, public space, and “thinning” — the low inhabitance rate of many new developments in burgeoning cities, the gradual disappearance of other cities, and the simultaneous emptying out of rural areas. This concept is typical of how Strelka aims to engage students with ideas and issues beyond the realm of a standard architectural education.

AMO and Strelka will take a series of questions as a starting point for its research: how is design impacted by economics, politics, and journalism? How can architecture engage with energy and sustainability beyond the scale of individual buildings — especially given the vast renewable resources that Russia can tap? What should Russia preserve from the Soviet era, and how is the issue of preservation embedded in new architecture everywhere? In a moment when vitality is shifting to the digital realm, what are the implications for physical public space?

Shumon Basar: Rem, you moved to London in 1968 to study at the Architectural Association, having already been a journalist and a scriptwriter. What drew you to the AA, what were you looking for in terms of an education and what did you find upon arriving there?

Rem Koolhaas: Essentially I grew up in a period – the sixties – where education was not necessary to have a life and so, contrary to what people think, I never went to film school, I never went to university, and was able in a way to go directly from school to journalism without any intermediate phases. I worked at the Haagse Post. It was really a kind of hardcore education where you started by emptying the waste baskets and then suddenly I could write things. And then I suddenly thought I wanted to be an architect. Back then, studying architecture in the Netherlands took on average of 10 years, and since I was 25 at the time I didn’t think it was a good idea. I asked Aldo Van Eyck, and he said, “Go to the AA.” It seemed to be a really inspiring environment, plus of course London was at that point a zenith of that world. So I came here and one thing that was totally disconcerting, like a time warp, was feeling like you were in the Nineteenth century, where you had a dining room and ladies in aprons. The city was ghastly. What I found here in retrospect was probably my first encounter with less rationalistic, less intellectually rigorous Anglo-Saxon thinking – a more intuitive, more playful, more cynical kind of environment. I learned an unbelievable amount from that, and certainly much more than I could have in any other educational environment. The best intersection was to meet Charles Jencks, with whom I became friends, and then Cedric Price. These two people were very important.

I think that you can explain lot of things in our work if you look for consistent modesty. But it is rarely done.

Did the ripples of May ’68 make their way to London and the AA?

Yes, they did. I had just come from Europe as a journalist – I had been in Paris not so much as a journalist but as an accidental participant, in Prague when the Russians came, and the continent was a very conflicted area undertaking huge manoeuvres against the different sides. At the AA, however, although the two sides were very present – some arch conservative world, some arch liberal world – there was no direct conflict. That seems to be one of the most amazing sides of the Anglo-Saxon mindset, this stretch to include extremes.

You moved to New York in 1972 – the same year that Venturi, Scott-Brown and Izenour published Learning from Las Vegas – and a year later the world entered in the oil crisis. You also began to teach quite soon after. Do you think that a bad economy was good for architecture education and theory?

It must have been in the mid-Seventies that the world “economy” really entered my consciousness. It wasn’t so much about a “bad economy,” but fundamentally about a reasonably poor or minimalistic financial situation that had been very stark after the war and that was slowly improving. So in retrospect the Seventies may have been bad, but it felt like business as usual. And the great thing is that education – and this is something for which I’m eternally grateful – made me completely oblivious to money. Therefore it was no big issue to come back to London to teach, even though the salary was microscopic. It simply was no issue.

It was an active period for treatises – your own Delirious New York coming out in 1978. Do you think it was a coincidence this all happened in the same climate?

The dust had settled. During the upheaval it was not really clear who was representing which side, what the issues were – there was just turmoil. Not so much about politics but on a hyperemotional level. Yet I think that the fallout crystallized a number of insights with regards to what the city needed to be. And maybe that was between the hippies and conservativism. It’s very strange – how quickly this rationalist movement emerged after the Sixties as a complete denial, in a way. It was produced by the Sixties but also it didn’t really embrace liberation. Someone like [Antoine] Grumbach in Paris was an active participant in the Sixties but in the Seventies started to assert strong rules of what the city should be like. The same two sides were effectively reconfiguring themselves in more contemporary identities.

Educational sites were incubators of new ideas and approaches …

Everybody had very low expectations of what means might be at your disposal. There were Xerox machines. But not a remote chance that you might be close to a printer. Being at a school meant that you dramatically extended your possibilities. All of us were looking for platforms in which we could pursue what we wanted to pursue. I first found the Institute [of Architecture and Urban Studies, New York], and then the AA where I could continue. We had very low demands. I was recently looking at the studio run by Venturi, Scott-Brown [and Izenour, who produced Learning from Las Vegas] and I think that was a very simple, minimalistic experience. Really incredible. That book shows how incredibly free education was and how we are burdened more and more by obligation. If you compare that to the experience of an average jury in a major American university today, you are comparing the spirit of openness to the spirit of anxiety – it’s kind of scary.

At one point your decision to remain in education hinged upon being able to conduct research with your students on “the contemporary moment” as opposed to “teaching” them didactically. This was the basis for the Harvard Project on the City.

Yes, exactly. I had a moment as a teacher here in the UK, sometime between 1976 and 1980, where I really enjoyed it – working with and discovering Zaha [Hadid] was deeply rewarding. But in the end it requires generosity, which is simply incompatible with the career or with the work of an architect. So, in the same way that I needed the support of the Institute [of Architecture and Urban Studies] in the Seventies, I then needed some other, external support to help me discover a number of urgent lacunae in my own understanding. It was in a very open form of something that was triggered by an acute awareness to quickly generate information about certain fields in architecture at the moment they were becoming urgent and crucial. One of them was the Asian story. The other was to consider which arsenal architecture might develop to engage with the development of the market economy. These were the most urgent kind of absences.

How does this relate to your recent experience as an educator?

Well, there was a moment when I was on the jury in an American school and the subject was how to renovate abandoned piers in Boston Harbor. When I looked at the student body, it was largely composed of people coming from cultures for whom the subject of an abandoned pier in Boston would have no relevance. They also possessed competences in many cases superior to those of the teacher. Some could speak Chinese, some had been designing traffic systems in Singapore for four years, and so on. So I simply began to realize that with globalization there has been a radical transformation of the student body, which is not a hungry substance that needs knowledge but rather, a group in themselves, competent people that only need to be provided with a different framework in order to become a productive machine, rather than hungry mouths. That was the real insight. Of course it had already been announced in the AA – when I was there it was totally English and I was one of three people in our year who were not; when I came back there were already people like Zaha [Hadid] and maybe a third of the programme was international. That exploration for me made it very important to think of education in a different way, accepting a different potential.

Learning from Las Vegas shows how incredibly free education was and how we are burdened more and more by obligation. If you compare that to the experience of an average jury in a major American university today, you are comparing the spirit of openness to the spirit of anxiety – it’s kind of scary.

It undermines the classical imperative of education which is that the teacher knows more, the student knows less, and education is redressing this balance of ignorance.

In order to trigger this direction, the position I took was one in which I knew less and they knew more, so it became mutually interesting to work together. There is a curious oversight. I think that you can explain lot of things in our work if you look for consistent modesty. But it is rarely done [Laughs].

Is consistent modesty a mode through which you operate in the world? Or is it something that happens in the background?

No, I think it really is a mode, a way of proposing the world.

How were you approached by Strelka, and what was it about their invitation that endeared you enough to accept the role?

First of all, Russia was the one country that was for me very important in my decision to become an architect. The model of the Constructivist architect was so close to scriptwriting at the time, and the step I was taking at age 25 seemed very small then. I was also writing a book about the [Russian] architect Leodinov. In that period I was in the Soviet Union a total of about 25 times. That was with a friend called Gerit Orthaus, an architectural historian who was teaching in Delft, who had a very rare quality that he could reproduce the exact authentic spirit of particular people that he was teaching as though they were there. He could give you the opinion of X, Y, Z. It was not his own interpretation, it was the real thing. That was such a strong presence, of the most ideal core of architecture and we tried to do this book together. With him I went to visit the widow of Leonidov and went to the Vhutemas [the Russian state art and technical school founded in 1920] and discovered underneath tables in kitchens incredible paintings by Leonidov, but also the kind of raw conditions that architecture had been living in, its intelligence. I have always been deeply engaged with Russia. There was the Hermitage Project, which was a renewed commitment. And so, with Strelka, this seemed a very good moment to reenter that world and to explore it – because it’s about curiosity on my part, about what Russia is like now and what can one do there. But this is also about education: if you look at the tests of how different cultures perform, you see that the Soviet system has had an incredible impact, and that that presence is still very high. It is really palpable today in Moscow, where all the people you meet have incredible mathematical talents, and an incredible and rigorous capacity for learning.

You mentioned before that often one of the motives to engage in a subject is an abiding sense of ignorance. But with Russia, you are re-engaging, rather than starting from a ground zero of knowledge.

Yes, but this kind of engagement was abiding on a personal level, and what is also really interesting here is the notion of an educational experiment which is not based on a school, which is not based on the onerous demands that such an institution might make – a commitment of a few years, for instance – and it is free, therefore has an experimental, Utopian dimension, seeing what you can do in reasonably short periods of time, and how you can possibly devise educational alternatives that are still more focused, more compressed, more efficient. Another interesting thing was to see whether we could develop interconnected subjects, and find a cast of characters, partly from whom we knew and who we didn’t know, that could engage in a collective speculation about that subject. I expect that if it works we will all benefit from it, not necessarily in terms of a coalition but as having been part of a particular period of collective thinking.

Immanuel Wallerstein recently talked about “de-commodifying institutions,” specifically things like libraries and museums, against a neo-liberal impulse that sees everything in terms of profit motivs. In Russia is it the case that this initiative is being taken by the private sector, by a new generation of philanthropists – in Strelka’s case, Alexander Mamut and Sergei Adonyev? Do you see this as a kind of inevitable trend?

I don’t see it as an inevitable trend but it seemed a kind of unique opportunity to see whether or not we can give it strength, whether or not we can make this into a portrait, a model for other conditions that might be compared to that kind of decommodification.

True experiments may only happen in an institution that hasn’t become an institution yet – i.e. when it is happening for the first time. That seems to me to be one of the exciting prospects of Strelka right now.

You don’t have to be a rocket scientist to discover there is a lot of angst in many educational institutions. With Strelka, it’s the appeal of being a part of something without a history, something limited in time. It is an exceptionally pure example of an experiment.

Are you optimistic about education as it becomes more and more subject to the demands of the private sector?

I am typically not impressed with the franchise model that they are experimenting with in the Gulf. There is an enormous effort to improve education in China, but still they are also tempted by other models. I have a sense that it is not a lost world – but that it is ripe for alternative models. Maybe the most important one is the way in which current culture, media and technology condemns people to a cyclical cancelling of their knowledge. This is one of the reasons why imagining an alternative to the four-year model becomes very interesting.

We go back to school again and again maybe?

Yes. You have the sense that every six years or so you ought to go back to some other kind of school, that you need additional food for thought. In this scenario, a future institution no longer works on duration but on intervals, on continued learning. This could be very fascinating.

When talking of experimental education one often goes back to Black Mountain College. One of its key influences was John Dewey, who said that a true democracy consists of an equation that includes at its core, education and civic society. Do you think Strelka ought to aim for these kinds of ambition, or is that a symptom of the nostalgic? Does its physical presence in Moscow allow for such civic potential to take place?

There’s that dimension in this initiative. Reading between the lines, it explicitly expresses a serious attempt to create a civic enclave. They have already succeeded in creating a kind of visible base, which is surprising, that will bring a strong and alive moment in Moscow, which feels really new and not debased. It seems like the two ingredients could co-exist.

The word “Media” has equal billing with “Architecture” and “Design” in Strelka’s mandate. Is this an ambition to turn the thinking and research over to public life?

Yes – I always thought that one of the ultimate frustrations of an architectural education was that it culminates in exactly nothing: you get end of year shows, but nothing else. Therefore if there was real content produced it becomes critical to get it “out there.” So perhaps another reason that Strelka is so attractive to me is that each of the people involved are in one way or another connected to media, and this suggests not only a potential access, but also a potential in terms of experimenting with different ways of communicating architecture.

I’m wondering if this educational aspect to your work can be considered a part of what you do in your practice within OMA, which we know as AMO; that is if it might be described as a separate but inclusive entity – otherwise, why is it important for you to continue to teach, in particular in venues such as Strelka?

Actually, in a certain way it is an AMO project. It’s simply one of the things we think we should do. The direct outcome of that perfect coincidence. But there is a private reason, I think I can say, and that is that 20 years ago – and I don’t know to what extent this is a generational issue – it seemed much easier to call together a group of ad-hoc people to gather around a particular issue and bombard it with speculations. You could get Chris Dercon, Hans Ulrich Obrist, Carsten Höller: they could simply come to the office. Everyone now is so engaged, so incorporated in a kind of seemingly rigid arrangement. So we look for other ways of finding that same collective ease of connection – despite everyone’s professional lives having become really, really rigidified.

Even though the illusion makes it look like it’s the opposite: that everyone is everywhere and doing everything with everyone else … Meanwhile, in reality, the notion of informality is disappearing?

Perhaps this is looking for another informality.

Credits

- Interview: Shumon Basar