CLOTHING OF CALAMITY: The Secondhand Trade in Uganda

|Declan Gibbon

Garments have many hidden lives and movements outside of high-street rails or Instagram posts, only in the last decade or so has the transparency of the industry been called into question. The majority of clothes are manufactured in third-world countries with cheap labour, transported via ship, sea, and truck and then reach retailers and customers. However, the energy and movements of the trade only increase from then; clothes are donated, sorted, and then travel back to third-world countries to begin a brand-new life. The interplay of numerous contexts and identities of clothing is often limited to the narrative of the first wearer or ‘thrift hauls.’ In Africa, in the hotspots of Kampala, Accra, Nairobi, and Johannesburg, second-hand clothing plays an important role in the lives of creatives, citizens, and post-colonial movements. Each year, 53,000,000 tons of discarded clothing are incinerated or go to landfills according to the Columbia Climate School, what they fail to mention is that most of these landfills are countries in the Global South. Due to American lobbying and worldwide pressure, Uganda, among other East and West African countries, receives 70 percent of imported used clothing. The second-hand clothing trade in Africa is extremely profitable for importers and the charities and companies in Western nations that utilize Africa as a waste-disposal. The mercantilist nature of the trade implies that African countries are trapped in the self-fulfilling inequality and exploitation of it, choice and agency are foregone in favor of money, greenwashing, and the world’s recycling.

Owino market is Uganda’s primary source of second-hand clothing, located in the country’s capital. Talking to traders and resellers in Kampala, several of them mentioned their excitement of receiving Zara clothes in bales drowned by cheaper-quality fast-fashion. The golden age of second-hand fashion is long gone. The clothes donations of the West are no longer the well-made and designer goods of the 1990s and early 2000s but the synthetical aftermath of the calamitous over-consumption of late-stage capitalism. The discourse on second-hand garments predominantly tackles two issues. First, the dumped clothing saturates the local industry with an uncompetitive source of textiles, stifling local businesses. This dumping pays little consideration to the fashion trends, economic conditions, and freedom of choice in sub-Saharan African countries. Ugandan, Kenyan, and Rwandan politicians have made numerous remarks on the trade’s degradation of African esteem, agency, and identity, viewing the reliance on second-hand clothes as humiliating.

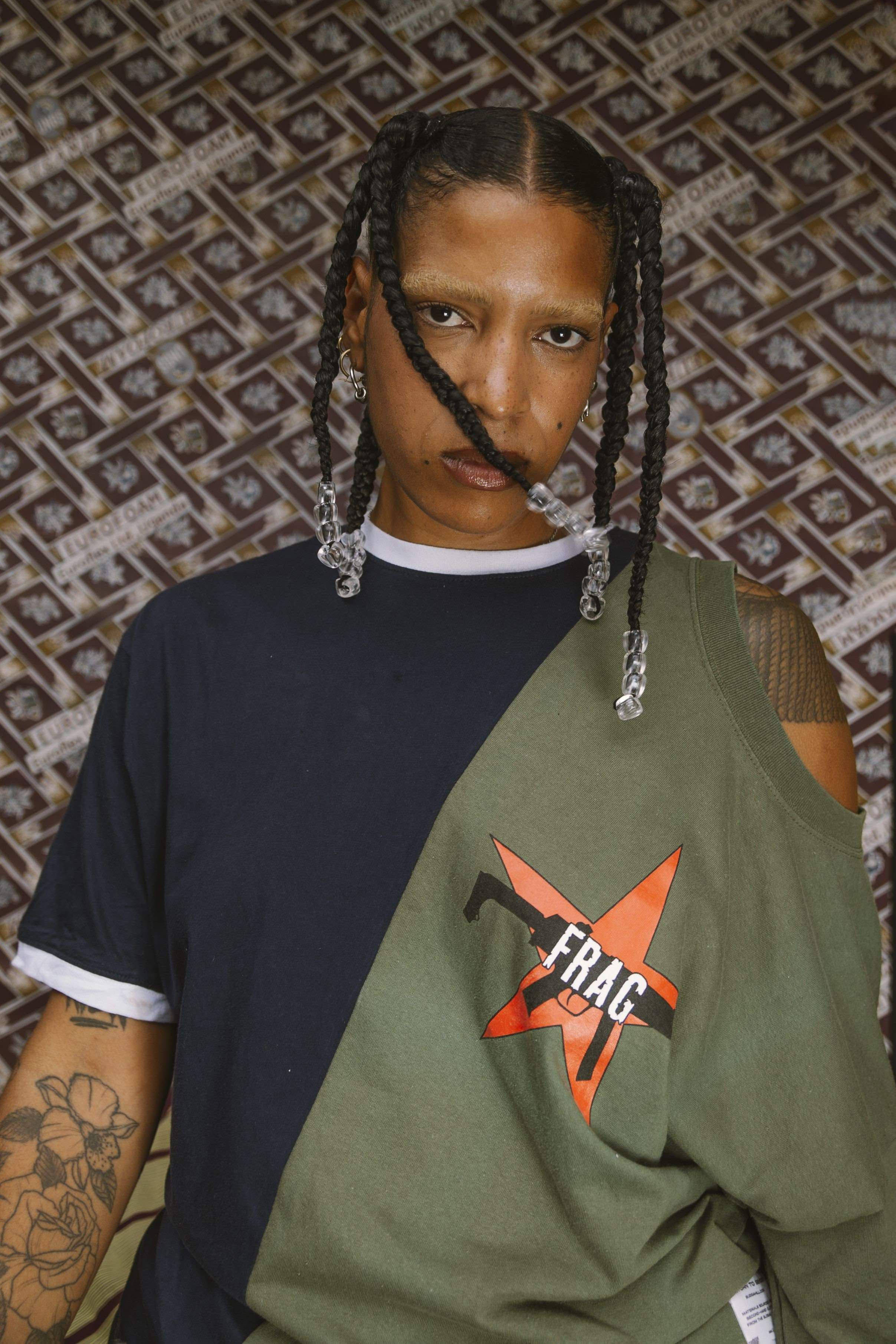

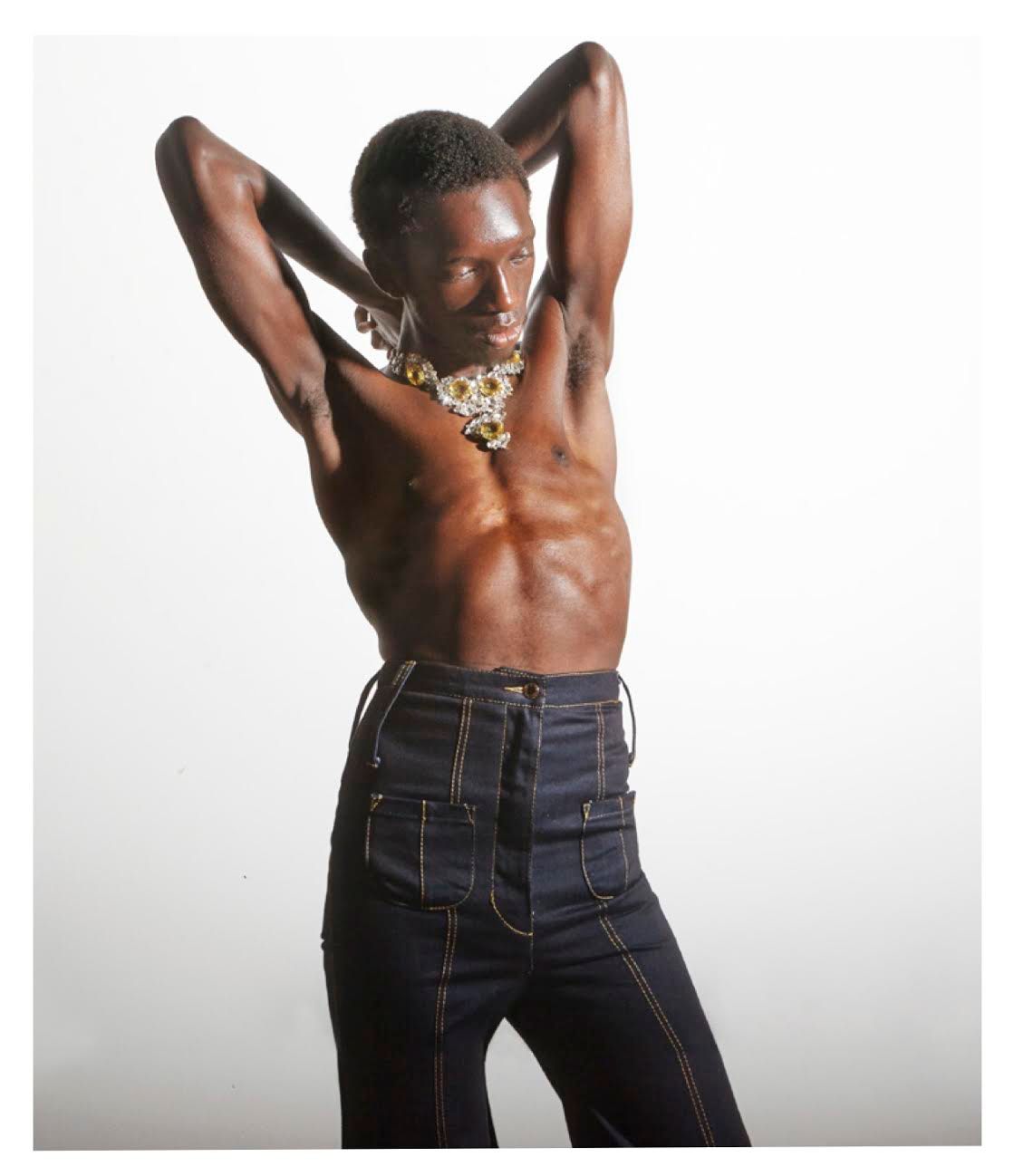

Bobby Kolade is the lead designer and owner of the brand Buzigahill, based in Kampala, Uganda. Kolade reworks pre-owned clothing into hybrid high-fashion designs, and all of his repurposed garments come with a passport, stating the country where the bale originates, their materials, and date of second manufacture in Uganda. Kolade was based in Europe for 13 years, making a name for himself in the high-fashion world, working for companies such as Maison Margiela and Balenciaga, before returning home. “In Europe, I wanted to create something sustainable. I had spent 18 years of my life in Uganda, and I had no idea that we produce amazing cotton, so I wanted to go back. It was the most obvious thing to do. When I returned, it really didn’t work though. The industry is deteriorating, and we only have two textile mills remaining.” Kolade continues, “We have never been able to recover from the political unrest and collapse of industry in the 1970s. I realized there was no way to work with Ugandan cotton to create a brand or develop anything. Again, it seemed like the most obvious thing to do was work with second-hand clothes because that is what we have in abundance without limitation.”

The cotton industries across Africa were initially developed by the British, who used forced labor to export to their industrialized factories. While Uganda has been producing cotton since the 19th century, the post-independence era saw the industry deteriorate due to political instability, civil war, and economic liberalization in the post-Cold War era. In the 1960s, Uganda was the largest cotton producer in Sub-Saharan Africa and produced on average 470,000 bales (185kgs per bale) of cotton yearly, of which 85 percent was for local consumption. “It makes more sense to export [high-quality cotton]. The price of local production is never going to be able to compete against the imported second-hand garments and fast-fashion,” Kolade explains.

Clothing consumption has drastically increased globally due to fast fashion’s ability to provide low-cost and on-trend apparel, but at the cost of the environment and workers. The average American throws away 37 kg of clothing a year, and the average consumer buys 60 percent more than two decades ago, keeping it for half as long. Only one percent of clothing is recycled to make new textiles, as the chemically linked polymers in the fiber of contemporary clothing degrade with washing and wearing. Influencers on social media gain social and ethical clout by donating to thrift stores the clothes they no longer wear, the problem is not the donation itself but rather the cycle of consuming more clothes than practical and then having an easy, and applauded, way to discard them, to make space for new ‘hauls’. Developed countries need to consume and demand less, clothing donations are for the most part, just throwing away garments.

The extraction of African resources have long fueled development the West. Numerous sources, who do not wish to be named due to the political instability and repercussions of the country, complain about only having access to bad fabrics that are toxic and that the government are the secret owners of second-hand and fast-fashion imports and as such, can avoid taxes. Local textile industries are no longer able to meet domestic demand; worn garments now make up over 81 percent of Ugandan’s clothing purchases. African countries on average export more than 90 percent of the cotton lint they produce, domestic cotton consumption has decreased by a quarter since the 1990s. Second-hand clothing and comparatively cheaper Chinese imports unfairly compete with underfunded, underinvested, and ignored local industries. The gravy-train of kickbacks, bribes, and corruption runs efficiently with the short-term trade in imports and duties rather than the long-term investment in import-substitution.

In his seminal work, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa (1972), Guyanese historian, activist, and author Walter Rodney argues that the combination of power politics and economic exploitation has directly caused the inadequacy and un-competitiveness of African political, social, and economic development in the 20th century. While it is argued that the book oversimplifies the complex forces and spheres of colonial influence and trade, yet when looking at the context of second-hand attire, one cannot help but see direct and stark parallels between his thesis and the lived experience of many Ugandans. He explicitly refers to the continent as “underdeveloped” rather than as “developing," to emphasize that the past and present exploitation of Africa has led to skewed balances of power. In certain spheres of industry and within the global order, Africa is more underdeveloped than it was 50 years ago when Rodney published his work. The imperial and contemporary mechanisms of under developing the continent are perhaps more pertinent than ever. Rather than being defined by a lack of resources, underdevelopment is caused by the uneven and unjust distribution of the wealth of these resources in the global system. He problematizes the economic, political, and social relationships with Africa and the rest of the world, which is explicitly captured by the crates of valuable raw materials leaving the ports of Africa and the returning crates of textile waste, now from both the West and the East.

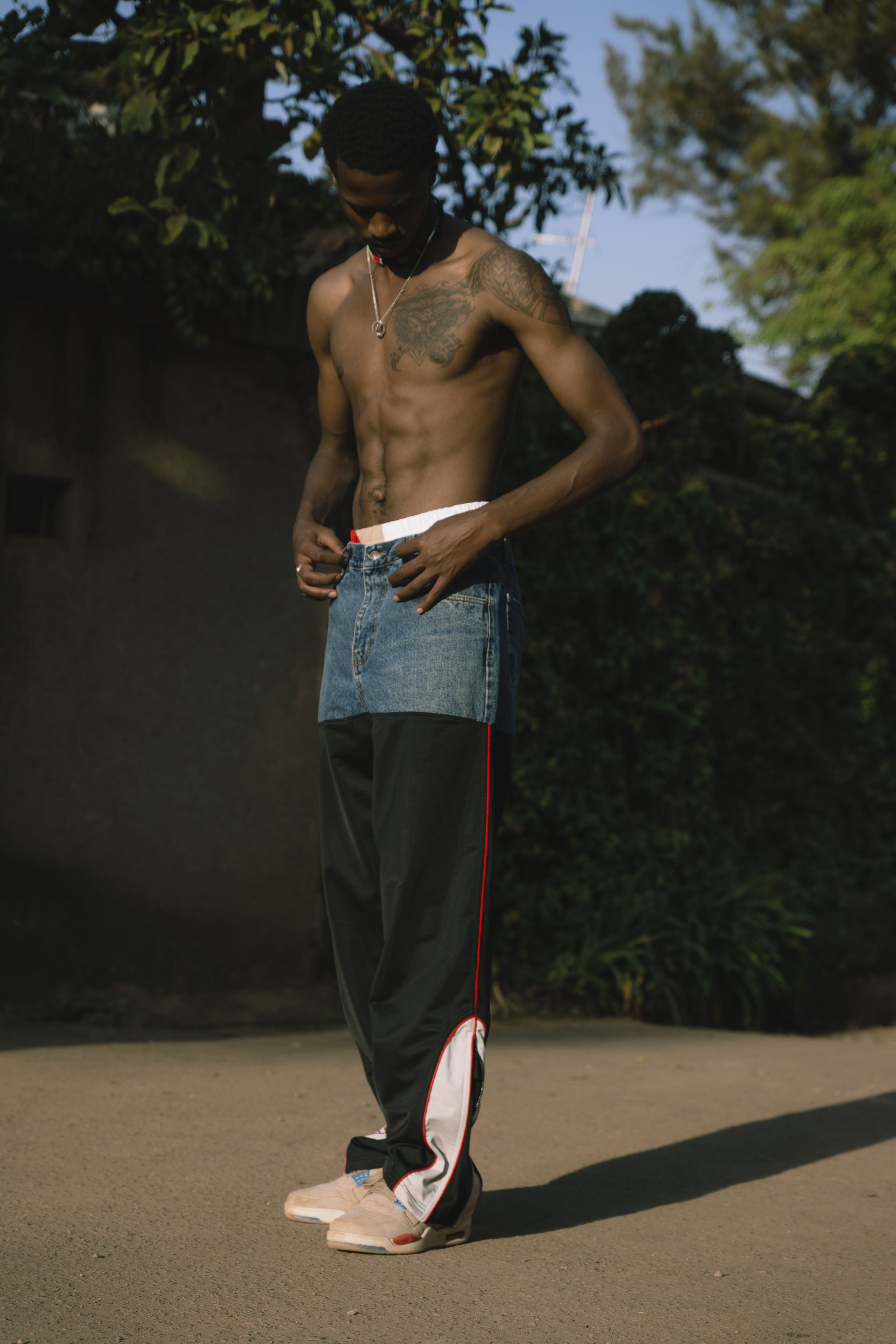

Due to the inaccessibility of quality textiles, economic limitations and bureaucratic barriers to entry, acclaimed fashion designer and founder of Kampala Fashion Week, Gloria Wavamunno has recently been forced to downsize her own brand, GWAVAH. She notes that, “The government have upped the tax for fabrics, and living expenses have gone up. The cost of electricity and frequent power cuts make using machinery unprofitable.” Musema Robert of the brand Msema Culture enthuses this narrative, saying that he is forced to use second-hand textiles in his designs as it is significantly cheaper and of higher quality than the available textiles. Robert continues that it is unprofitable to use new fabrics as the price of his design cannot compete with the availability of cheap second-hand clothing. Robert, for the most part, has now given up on making his business accessible to the wider population. “When I mix second-hand denim with African patterns and fabric, I target a Western audience because they understand the story [African patterns and environmentally friendly textiles] and have the purchasing power,” Robert comments. Catherine & Sons, a clothing line also based in Kampala, aims to alleviate the flood of secondhand clothing by similarly dissembling and reassembling secondhand garments, using them as raw materials in a closed-loop value chain. Founder Edward Sempa says, “we focus on using secondhand denim and linen because it’s easy to work with and we have no other option. It is really hard to scale it up.”

The re-use and thrifting movements in the West have ensured that most high-quality and sought-after garments do not make it to Africa. (Fast) fashion brands host secondhand clothing marketplaces online and in their stores, which further limits the export of better quality goods. On the surface appears as a shift towards circularity. In practice, however, the core business model benefits from and therefore maintains models of overproduction. Take-back schemes promote further consumption by offering vouchers for used clothes, which probably end up in landfills anyway. Remake’s 2021 Fashion Accountability Report stated that there are no brands able to prove their circular initiatives replace the production of new clothing. Resale runs in parallel with traditional retail and customers are stimulated to buy more with their morals greenwashed by persuasive PR campaigns. “Why would the collection centers put 100 percent wearable clothes in a bale? You are sending it to an importer who pays you before the goods even arrive who then sells it to a vendor before they even open it. Once the vendor opens it, who the fuck cares? They can't return it. The small guy gets fucked as always,” Kolade loments.

Kolade also runs the podcast Vintage or Violence together with filmmaker Nikissi Serumaga. Vintage or Violence uses the lens of the secondhand clothing industry to analyze and discuss economic inequities as well as to reimagine a future for their local context and industry. Kolade and Serumaga have both lived across Europe and America and have been involved in the trade in numerous contexts. The crux of the matter is context and agency. “I went thrifting last month in Berlin with a friend, and we are looking at the same brands we get here, but they have all the cool stuff. We get the lower grades of the same brands. I was just offended, really offended,” Kolade recalls. The same goes for Surumaga, who says in the podcast about her experience thrifting in Toronto and Johannesburg, “vintage implies choice. It implies exploration. It implies safeguarding, keeping, and enjoying. Secondhand clothing here, and why we call it violence in our podcast is because there is no choice. There is no option. Where is the joy in no choice?”

Cameroonian academic Achille Mbembe’s book On the Post-Colony (2001) deals with the topics of violence, privatization of the public, and the appropriation of livelihood. The relations between salary, citizenship, and clientelism in Africa are intrinsically tied to government allegiance. In colonial times, proximity to governments, colonists, and officials granted access to resources and opportunities that the “wretched” would not be able to access. These debates of agency and power and the proximity to government, whether colonial or democratic, narrates the story of secondhand textiles. Despite being a self-funded recycling business in the West, the clothes are still viewed as charity, as goods that Africans are not able to access, and as a humanitarian need. Ato Quayson says that the book explores "the complex interplay of consent and coercion in the post colony and the carnivalesque disposition of both rulers and ruled in the production and maintenance of hegemonic relations of power and subversion.” Kolade remarks on the Ugandan environment that it “isn’t made for start-ups, or anything of this nature, to succeed. My accountant told me the other day that if we do everything by the book, we are never going to make a profit.” Exploitative trade practices continue while Western ignorance and fetishized projections of guilt further exacerbate the extent of the trade.

Cheap and low-quality fast-fashion imports and the slowly degrading quality of second-hand imports are direct competition to local brands and factories, and surprisingly, these two industries often work in tandem. Wavumuno complains that China is her big competitor because of how quick they can copy her designs and fabrics and then produce and distribute them. She continues that “A lot of government officials get fast fashion clothing from China and get it in here tax-free or even by labeling it as second-hand.” She believes that while fashion is evolving because of the internet and trend-first fashion is everywhere, the clothing available in Uganda has “fabrics that are toxic, and the clients of these imports don’t mind as long as they are wearing Beyonce’s or Rihanna’s look.” Kolade backs up these claims, “we had this one story where imported shoes were rubbed up a bit to make them look secondhand because no one will buy a brand-new pair of shoes from China. Clothes and shoes made in China for Africa are way more inferior than the products made for Europe or America, so it is better to buy them secondhand.”

The most important question about the secondhand trade, cheap imports, and decreased production is: who gets to decide? Colonial powers got to decide the cultural and institutional fabric of society for a century. America got to decide neo-liberal policies. Collection centers in the West get to decide what they import. Fast fashion gets to decide what they dump and where. Governments get to decide what they invest in. However, secondhand clothing imports can contribute to the textile value chain, as we have seen with Buzigahill, Gwavah, Catherine & Sons, Msema Culture, and others, through the up-cycling and appropriation of ‘landfills.’ Africa is the untapped, and final, frontier of significant global growth, rather than as a market of extraction and import but of cultural and creative export. The globalization of the world is explored through the repurposed clothing of Kampala's fashion industry, the transformation of the discarded to an item of higher cultural and monetary value is a striking example of working with the odds piled against them. Returning these garments to the sender is holding a mirror up to the obese face of fashion, its guzzling mouth, fetishistic eyes, and over productive glands. The industry can’t help but see the flaws in its past, present, and continuing trajectory of exploitation and extraction. Slowly but surely, the fashion coming out of Kampala is the watershed that is eschewing the destiny of clothing and enthusing an ethical movement of thoughtful consumption and creation.

Credits

- Text: Declan Gibbon

Related Content

Menswear Metaphysics: GRACE WALES BONNER’s Bejeweled Visions

Between China and the Arabian peninsula, a “maritime silk road” powers global capitalism – even in the age of the cloud. LALEH KHALILI explains.

Legion of DUMA: Nairobi’s hardcore duo premieres a new video

Post-Food, Post-Fashion: NHU DUONG Makes Uniforms for SOYLENT

The First Fashion Blogger and the Dandy Ethic of Capitalism

Texting with HERON PRESTON Before the Presentation of His First Collection