What’s the value of time that don’t end? JEREMY SHAW's Phase Shifting Index

|William Alderwick

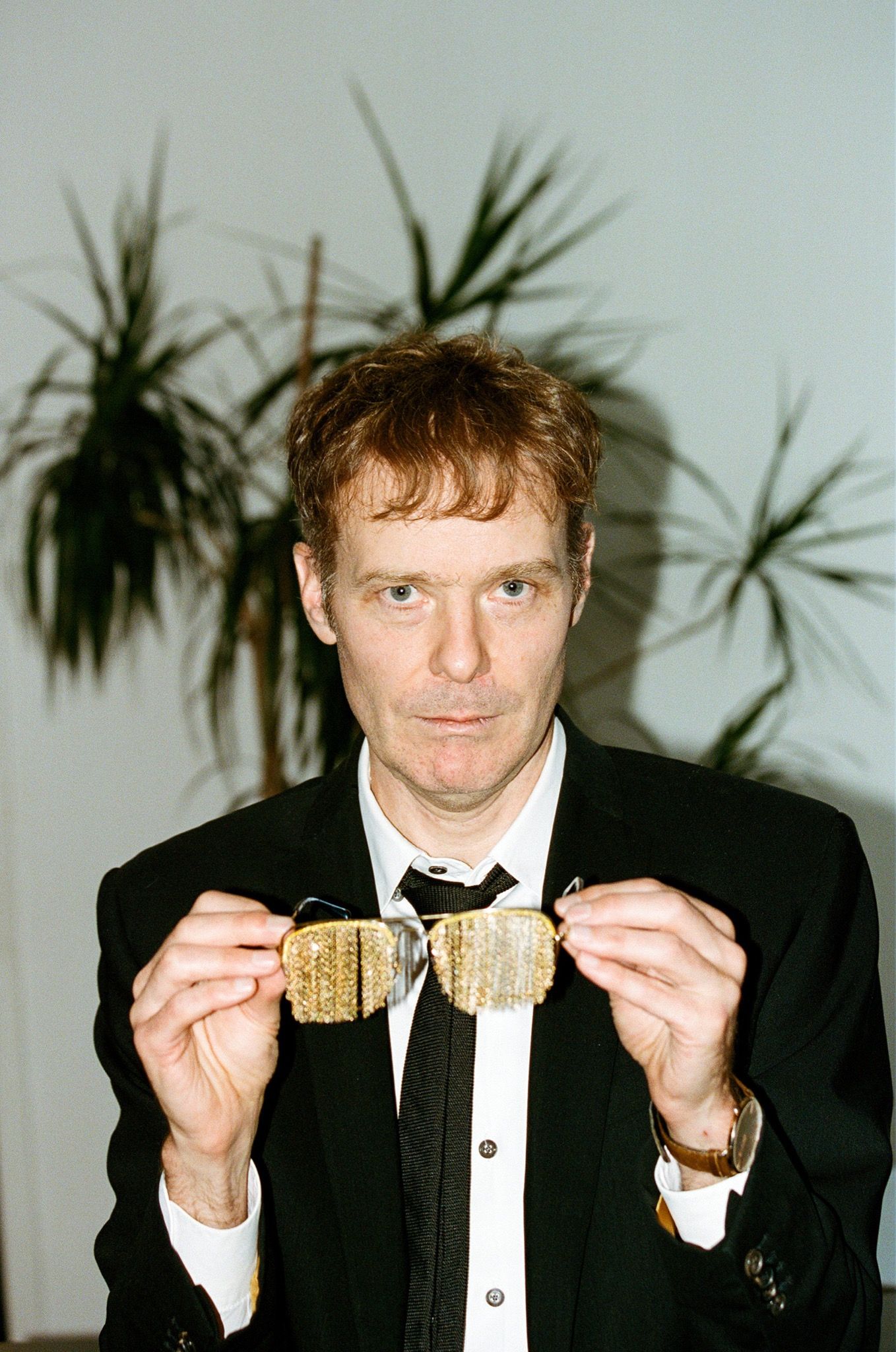

Phase Shifting Index, a major new exhibition by the Berlin-based, Canadian-born artist Jeremy Shaw opened at the Centre Pompidou in Paris in late February. The work is composed of seven films displayed on separate screens, each depicting a group of people try to escape from their world into a parallel reality using dance or therapeutic movements as a conduit. Through this post-documentary mix of formats, Phase Shifting Index explores the potency of belief systems to shape and transform our lived experience.

This is the largest and most expansive work yet for the artist, whose work combines conceptual rigor with a deep fascination for subcultures and the transformational effects of drugs. The piece builds on Shaw’s earlier works, such as the 2004 film DMT, which documented subjects under the influence of the titular psychedelic as they recount their trips in voiceover. Released a year later, 10,000 Hits of Black Acid takes a similar subject but bends sinister, featuring a sheet of LSD blotter paper smothered in solid black ink that creates, in Shaw’s own words, “a Malevich-like void in which all traces of actual LSD and subsequent possibility of enlightenment are lost.” Best Minds Part One (2008) comprises slowed footage of straight-edge hardcore kids dancing at a concert, their movements at once violent and cathartic. This Transition Will Never End (2008-ongoing), an ongoing compilation of appropriated wormhole footage from film and TV, documents cinematic representations of the theoretical interstellar phenomena, while also crafting a single endless sequence that jumps from one reality to another. But, perhaps more than any of these, the Quantification Trilogy produced between 2014 and 2018 most-clearly informs Phase Shifting Index.

Shaw gained international attention with Quickeners (2014), and then its follow-up Liminals (2017), which debuted at the Venice Biennale in 2017 – where the artist’s signature trippy data mosh visuals dominated social feeds throughout the vernissage. I Can See Forever (2018) completed the Trilogy, with each quasi-documentary or ethnological film in the series purporting to be an artifact from the future, exploring the various repercussions of a fictional event referred to as “the quantification”: when science discovers the formula for (or “quantifies”) spiritual experience, reducing all experiences of revelation to a predictable and thus reproducible neurological pattern in the brain. In other words, it’s a kind of scientific proof for the non-existence of god.

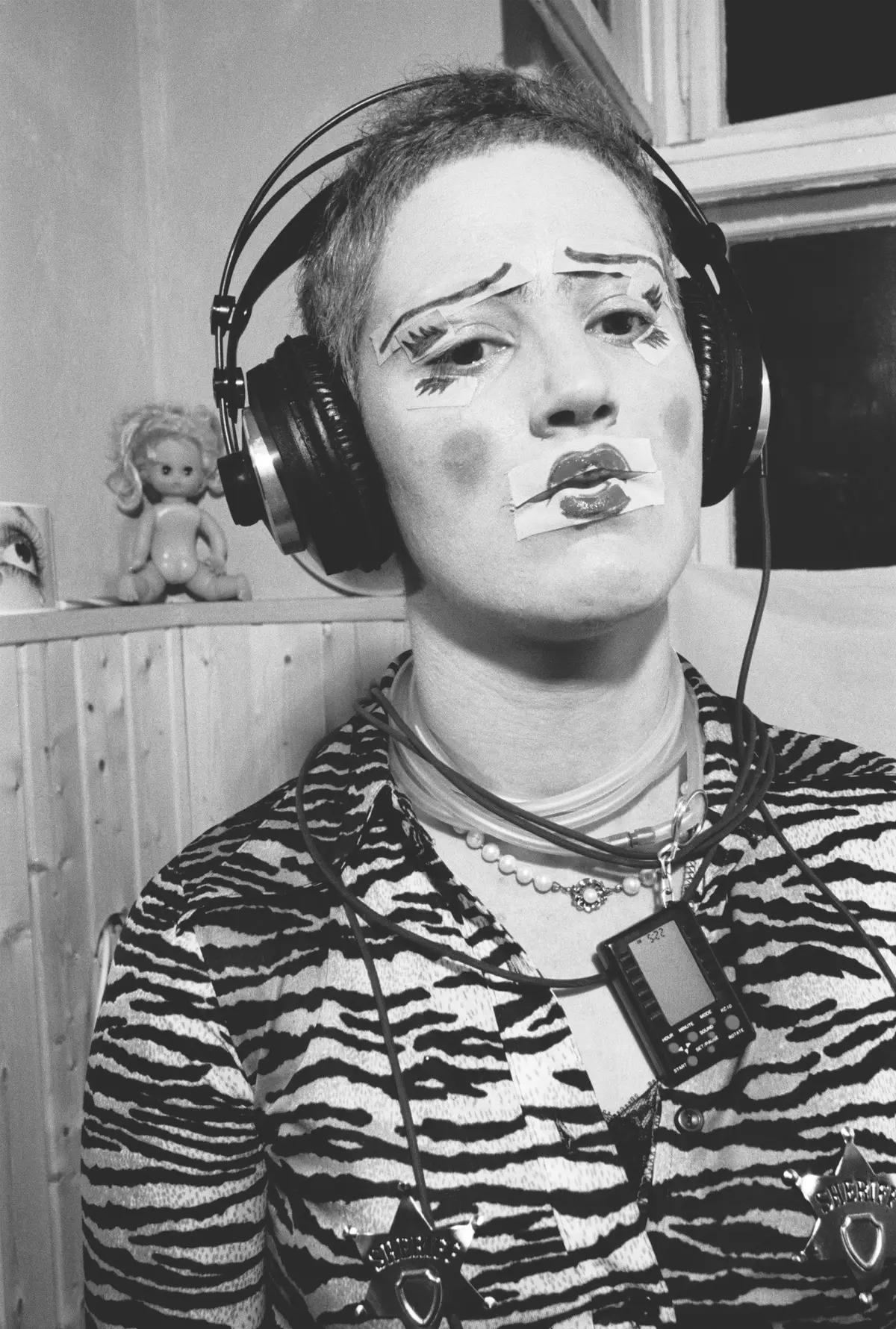

Quickeners saw the artist transmute found footage of The Holy Ghost People, an archival documentary of Pentecostal Christian snake handlers. Shaw rendered their voices into a glossolalic senselessness, interpreted for the audience via subtitles and a voiceover that recalls a 1950s style ethnological study or public service broadcast. Within the video, this transmission presents a mutant AI hive of quantum humans living 400 years after quantification, who are attempting to rediscover some lost sense of individual spiritual purpose through adopting anachronistic practices and rituals. Set 200 years earlier in their shared timeline, the sequel Liminals profiles a group attempting to transcend corporeal reality into an indefinable liminal space in order to escape the existential threat posed by the death of belief that would follow quantification. By removing the sense of fate, meaning, and purpose provided by spiritual experience, quantification sets humanity on a path to extinction. The Liminals group naïvely experiments with assorted objects, disco balls, and dream machines – new age paraphernalia shorn of their contexts and functions – chanting and swaying formlessly together in footage recalling some 1970s primal scream therapy or cult news report.

I Can See Forever (2019) brings us back to the immediate aftermath of quantification through a 1990s-sports documentary style profile of Roderick, the sole survivor and offspring of a group of experimental subjects infused with machine DNA. (The experiment was fatal for all other subjects because their networked m-DNA took over.) We meet Roderick as an adult, learn of his love of dance and witness a virtuosic, almost inhuman talent as we see him dance alone in a white studio space – a sumptuously beautiful performance of endlessly free-flowing improvised movement that morphs into digital distortion, carrying us over the edge of the film’s (and the Trilogy’s) vanishing point.

The Trilogy has a loosely consistent, potentially linear timeline, yet each episode presents equally alien propositions and is stylistically different enough – featuring changes in film stock, voice, and perspective – to convincingly come from radically different worlds. The narrators drift closer to the audience over the course of the films, from an anonymous external authority to a more intimate touch. Layers of each work elide and flex, opening space for interpretation, distance, and doubt to slip between. Nothing is quite what it seems, and within each film its other layers always seem to pull it elsewhere. These oscillations, almost a dance in themselves, build in intensity and frequency until reaching a crescendo together, when it feels as if the medium we’re immersed within can no longer contain its subject – sound blurs, frames stutter and grind, light cascades and the liminal bleeds. Across the distance of his work’s humor and criticality, Shaw seems be daring us to go along for the ride: how long do you hold out?

The temporal displacements of this narrative envelope help to create a cognitive dissonance that belies easy critical readings of the material. Ultimately, we do go with the flow, surrendering to the trip Shaw takes us on. In this way, the videos can themselves be read as attempts to make space for an experience: by attempting to not just frame a point of but also make it and represent it to the viewer, they can be understood as works about transcendence, as well as works of transcendence.

These outward signs of subjective decompression echo the phenomenological symptoms of perceptual dissolution, the de- and incoherence one encounters through imbibing psychoactives or pursuing techniques that induce trance states. Shaw’s signature data-mosh visuals – at once archival and embodying the technical representational possibilities of their time, in terms of formats, resolution, and CGI effects – also reach towards timelessly-flattened representations of subjective transcendence, of liminal states and enlightenment. The ultimate degradation of medium, the collapse of representational integrity, is an empty set, telescopically removed from its semantic situational baseline toward an abject emptiness. Its vanishing point?

The trajectory of the Quantification Trilogy takes us toward a radical interiority, or subjectivity as a mediated quantity. But Phase Shifting Index also suggests the possibility of something beyond quantification. More accessible, immersive, and larger scale, the latest work offers less to watch 1:1, alone in the corridor: the work is a communal experience, its “revelation” promising to emerge in the midst of the room, somewhere between its observers. It addresses a wider public with the aim to carry them further – and with less to hang on to – beyond its event horizon.

Shaw’s is a world of synthetic revelation, beyond DMT psych-revivals and mainstream wellness commercializations, beyond personal transformations after encountering tulpas, machine elves, or liquid fifth-dimensional blobs of living information on some trip. It’s a future where that Saint Paul road to Damascus moment becomes as available as your daily caffeine fix from your local barista, or perhaps more appropriately today, a revelation brought to you on-demand à la Netflix or Prime (as watched on the TV sets in I Can See Forever).

Quantification asks us questions of what happens after the death of religion, of belief, and of meaning sought in the unknown. What are our after-lives if everything that makes us human is reducible to science, if the universe is radically determined, even in the most profound moments of spiritual awakening? Ray Kurzweil’s technological “singularity” fails to account for the moving vantage point as we live through moments of historical inflexion. One could contend that this is precisely what Shaw’s work is trying to resolve, heralding some psychedelic apperception of transcendental temporal situatedness – whatever the fuck that looks like.

In our worlds of post truth, fake news, and social bubbles, the insular narcissism of a technologically-perfected consumer – for what else is the quantification of religious experience but the end game of capitalism’s virtual colonization of our souls through desire? – the existential dimensionalities engendered by multiverses of parallel realities are vital for transcending our mediated and pre-programmed limits, for reaching an/any other, and thus for the very possibility of connection, community, and love. Such is the Badiouian adventure of love: one becomes two, becomes infinite – an attempt one might anticipate lurking within Phase Shifting Index.

In the aftermath of watching the full trilogy on its first screening together at the Tate Modern in late 2018, and in anticipation of where the artist would go next, I spoke to Shaw through the development of Phase Shifting Index: first in Berlin at his flat, then in early production stages over Skype with the artist, and finally as the finishing touches were being made ahead of the opening.

William Alderwick: You’ve been in Berlin now for eleven or twelve years, but you’re originally from Vancouver, right? How did that move affect your work?

Jeremy Shaw: Yes. It was good moving here from Vancouver, which was super academic and rigorous at the time. I think it was starting to breed caution into my work. I found that being surrounded by certain conceptual practices — where you could tell someone everything about a work, literally, and walk away not needing anything more — became stifling after a while.

As if the work is reduced to the wall copy next to it?

More that there was a mentality, back then, that if you weren’t able to explain every single detail of the work you were making, then it wasn’t valid. That seemed to be the overarching manifesto of the Vancouver art world at the time. It was actually a very beneficial thing to be under for a while, to learn to be responsible for what you’re making, but to break [away] was also good, and necessary in order to evolve.

Did the energy and lifestyle of Berlin bring something else to the work?

I’m not sure if Berlin, specifically, brought something else, but the amount of space and time that the city granted me certainly aided in discovering new ways of working. The pre-Berlin works were a much more distant, critical take on altered states. After a few years living here, in 2012, I was invited to take part in a show titled One on One at Kunst-Werke, which was curated by Suzanne Pfeffer. The premise was that every work was only to be seen by one person at a time. So you could either make a work that people could engage entirely on their own, to have a solitary moment with something, which would be quite a beautiful notion, or you could really get specific and enforce an exact way of viewing — which is what I did.

I made a video called Introduction to the Memory Personality, that I wanted to feel like a strange clandestine hypnosis tape, something you might have found in a thrift shop discount bin. The video would only play when you sat down in a chair fixed directly in front of a rear-projection in a small container-like room, and it would shut off if you got up for more than a few seconds. You had to watch it from that exact position. I didn’t want the piece to be about hypnotism, I wanted it to be hypnotism. I wanted it to actually be the thing it was discussing — the artwork truly as this experience of watching this haunted tape. I wanted you to feel that, by watching it, you had just been implicated in something beyond the experience, like it tainted you somehow and now you were part of its story. That was a huge turning point for me; it was the first time I went for eliciting the phenomenology that I had only been talking about before. I really attempted to induce an altered state in the viewer.

From there, the work definitely became less tidy, less resolved. I got more and more into ideas of manipulation and cognitive dissonance, which was exciting because I’ve always loved being tricked by art and films, duped, not knowing if things are real or fake, or having super drastic plot shifts.

One press piece described your films as “para-fiction.”

I like saying “post-documentary.” That doesn’t necessarily tell you the film isn’t real — but it implies some new form or movement of sorts, something beyond traditional documentary. I try to keep the suspension of disbelief as long as I can, and it begins with how the work is labeled. But it’s nearly impossible these days. Like in the case of the premiere of Liminals in Venice, within 20 minutes of a press pre-preview someone had recorded the climatic rupture scene and put it on Instagram. You just have to rely on the world’s increasingly collective sense of amnesia in these cases, I guess.

When did you first find yourself attracted to the subject of altered states?

Honestly, since I was very young. I can remember that, as a kid, I would play these games with friends where you choke each other in order to pass out, and then come back from it moments later feeling totally dazed — like time had stopped. I was raised Catholic, so the notion of life-after-death, of something greater and beyond, was always present from a very young age as well. I also had a copy of Pink Floyd’s The Wall that I bought at a garage sale when I was 7 or 8 that seemed to really set the stage — I would listen to it over and over while staring at the illustrations on the inner sleeve, trying to make some kind of sense of it with my pre-psychedelic mind. I started experimenting with drugs quite early in my teen years and became consumed by music, dancing, clothes — certain subcultures I was participating in and others I would monitor through music videos and magazines. I also started reading lots of Beat literature, which lead to McKenna and Huxley — very common entry points, really. Later, when I started to become more serious about making art, my focus shifted deeper into other people’s dancing, other people’s spirituality and drug use — their ways of attempting to transcend, in a more universal sense. And, from there, I became consumed with the belief systems that form around these aspirations as well as the scientific attempts to locate and explain them. There are massive grey areas between transcendental experience and the scientific readings of it that I continue to find fascinating.

Are your films attempts to share your own experiences?

In a sense, yes, but not explicitly. I mean, I’d love to be able to relay that renewed sense of wonder that taking acid for the first time instilled in me. I was truly moved by LSD — totally shaken. Taking it changed my life, as did ecstasy and, later, DMT. These were real, key moments, where your mind is blown and you really do have that realization there’s more available to us than the reality in which we’re situated, or at least that we recognize on a day-to-day basis. It may seem naïve in hindsight, but the effect of those experiences on me as a human is incalculable. So I do think [communicating those experiences] has been a constant desire in some capacity — almost subconsciously — but also detailing the fraught attempts to do so. The inability to articulate such profound experiences is something I have often embraced with my work as well.

Your film Quickeners uses found footage from Holy Ghost People, Peter Adair’s 1967 documentary about Pentecostal Christians in West Virginia, correct?

Yes. I actually saw the film in art school though I don’t have a vivid memory of the context except for being totally captivated by the snake-handling scenes. Later, I came across an original 16mm print on eBay. I was sitting on it for years, knowing that I wanted to work with it but not sure in what capacity. It was only in 2014, when I had my first show coming up at König Galerie, that I decided to take it further. It wasn’t enough for me to simply appropriate the footage and make a music video-like piece, as I may have earlier on in my practice. I felt the need to sandwich it within something more expansive and narrative.

I saw Quickeners as an opportunity to alchemically combine many of my influences. Under the banner of science fiction, I flattened them into the same space without hierarchy — or, at least, the hierarchy became a debated element within the piece.

What’s the “quantification” referenced in the Trilogy’s title?

It’s a [fictional] moment in time where science discovered that all spiritual experience, no matter what the practice or religion, was created via an identical set of neuro-synapse firings in the brain. In turn, these could be predicted and completely deduced or explained. Therefore, almost the entire population took this as evidence against their own experiences, discounting their validity, and spirituality was essentially abandoned.

It’s the idea of science empirically explaining transcendental spiritual experience. If that was to happen, would it discount the experiences? Does that mean you didn’t see God, if they can tell you exactly what happens in your brain when you feel that you did? Or would that further confirm it?

As a result of this loss of spiritual practice, the area of the brain that was allocated for faith atrophied over time. Then it was discovered that it had actually become a necessary part of human biochemistry and thus, humanity is set on a countdown to extinction. That’s the “Announcement.”

Each film happens in the wake of some landmark event, whether it’s the “Quantification” or the “Announcement” or the “Acknowledgement.” Was that to distinguish these fictional narratives from reality?

It’s a way to establish these non-hierarchical sci-fi landscapes quickly. I rely on a very dramatic, dense first chunk of narration to set the tone and place the viewer within this paradoxical temporal zone. That intro text is also a real trope of science fiction, which is something I enjoy working around.

“A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away” —

Exactly. Sci-fi so often presents you immediately with something totally upending that you just have to go with it. The catch with mine is that they’re aesthetically presented as a historic reality.

Why adopt a documentary format for the films?

I found reworking the archival verité material of Quickeners so effective that I wanted to keep pushing in that direction. I wanted to continue manipulating time and history — or at least appearing to do so. Using the conventions of documentary facilitates this because people generally don’t question them. You almost immediately take them as fact. Especially when presented on outmoded mediums, a viewer generally trusts something that appears to be documentary when it’s on 16mm film or VHS. It’s history, it happened. The manipulation becomes more difficult to decipher. That is a huge part of the strategy with all these films: gaining a comfort and trust from the viewer that can then be subverted.

Because the tropes of the documentary format you adopt are so familiar, even if you walk in half-way through your films, you can still pick up the thread. The sense of familiarity carries you. This makes what happens next — the moments of rupture — hit you even harder.

Yes, they are quite strategically edited to really disrupt at these ruptures. They even shift in medium from the outmoded to something very contemporary. Aspects ratios change and audio becomes surround. I edit quite musically, in a sense. I think of tempo and pacing a lot. I watch the films again and again and again to establish a rhythm to the editing and think them out, much like writing a song. I’m constantly drawing them out in my book in a kind of bastardized musical-visual notation.

The Trilogy suggests that virtual reality and AI might make us lose what is essentially human. Is this something you believe?

I think it’s very hard to comment on something like that while living it. I’m as excited by these ideas as I am afraid of them. That’s how I make art, in general. There’s criticism and celebration — a skepticism to my belief. I do believe that there’s a danger of losing certain aspects of what keeps us connected together as humans, physically and mentally, emotionally, but then I’m also very excited by the prospect of what would constitute some kind of cyber-spirituality. Where could that take us if the rest of this fails?

There’s certainly a sense of cognitive dissonance involved in watching a documentary ostensibly from the future. This is compounded by the lack of any explanation for how these documentaries from the future actually get to us. The audience has to accept that, in the future, a wireless AI hive of quantum humans is making 1960s-style ethnographic films about itself, and that’s how it communicates.

Sure, the films are totally absurd and perverted, in a lot of ways. They are very intentionally overloaded with discrepancies that you don’t have time to get super deep into investigating. You have to basically give up on reason in order to follow the story, otherwise you’ll spend the entire duration trying to figure out what’s what.

The performance and choreography at the end of I Can See Forever is remarkable. How did that come about? It was shot before Liminals, right?

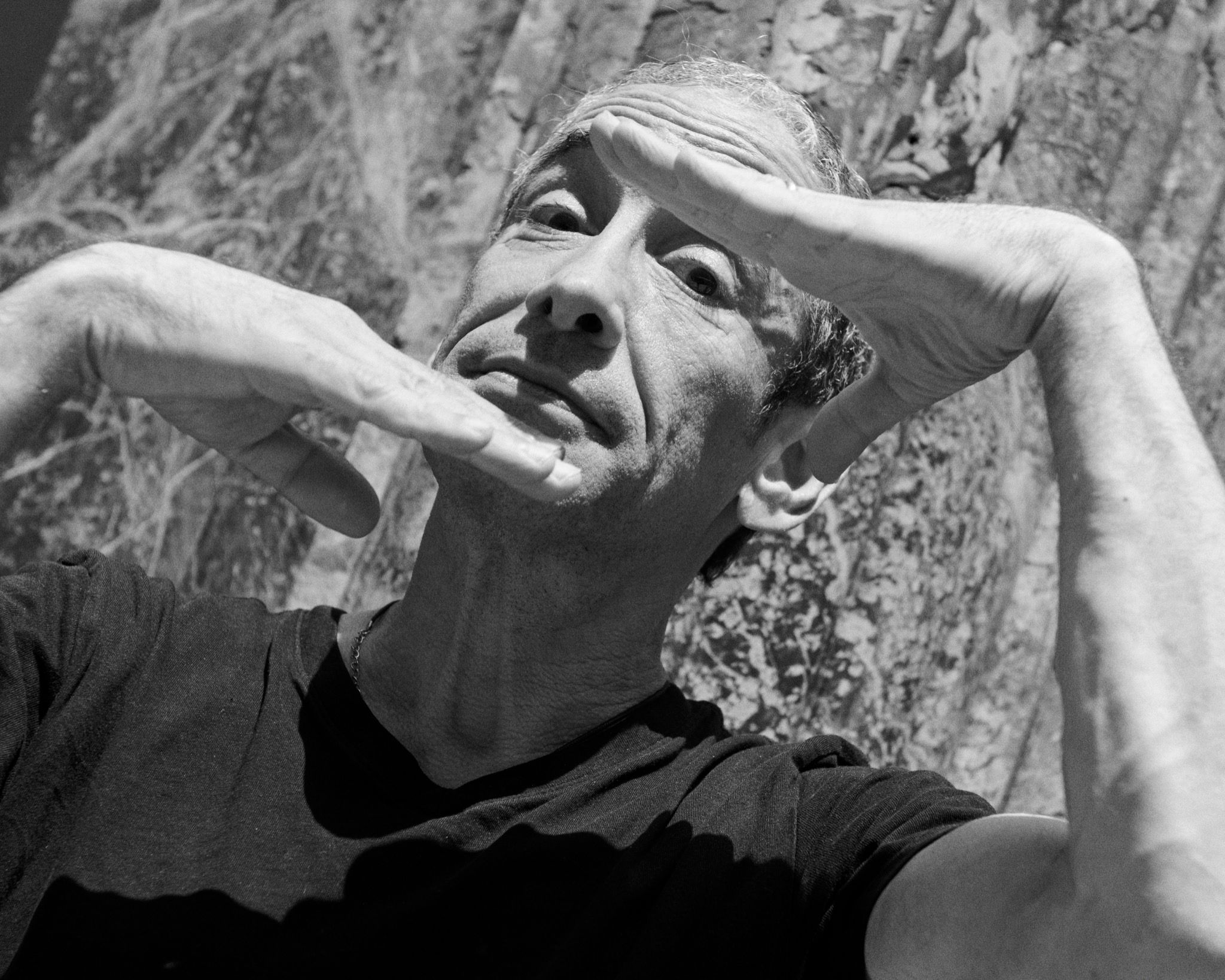

Yes, that was pre-Liminals. Roderick George, the dancer in I Can See Forever, is an ex-Forsythe [Company] dancer who I first encountered during a Tino Sehgal performance at Martin Gropius Bau. At the end of each day, all the performers would gather in the center of the exhibition space and do some kind of freeform improv. The day I visited, Tino had instructed Roderick to dance a solo – the only time this happened in the exhibit’s three-month run. I was totally hypnotized. Instantly, I knew that wanted to work with him.

I met [George] after the show and we talked for months about making a film but couldn’t figure out exactly what I wanted to do. So, I set up a shoot, and somehow had the foresight to put him in a 1990s look. We worked with a really base bed track, and I asked him if we could use a set choreography for the first part that he could repeat, so that I could cut it with continuity. The second part, though, is totally freestyle – and that is where he shines the most.

That’s how I Can See Forever initially came about: I was simply enamored by the way Roderick moves, and saw something totally transcendent in his virtuosity. That’s so rare. There are virtuosos, but how many people can fuck with the fabric of time? Like Roderick really distorts my perception of time when he’s dancing, you know? So, I had that raw material of the dance sequence, went off and made Liminals, and then came back and shaped it into the story of I Can See Forever. The entire narrative of the film was reverse engineered in order to work around this dance scene that had been shot 18 months prior, and to fit into the timeline of the trilogy preceding Liminals and Quickeners.

When he’s dancing, it seems like the movements he makes are never fully resolved – they’re always becoming something else. Any reference to a form or style morphs into another before the movement’s done.

Yes, you’re never quite able to digest how Roderick dances – he’s one perpetual series of virtuosic maneuvers folding in on each other. That’s what makes it so hypnotic – he’s like a human fractal.

After the wormhole-rupture at the end, I Can See Forever loops back to the beginning, and you’re in this slightly drippy, bleached-out, almost-chill-wave-music-video sunset, as if you’re watching the actual television depicted in the film.

The last two films of the trilogy both have four distinct stages: the documentary, the cathartic dance, the meltdown, and then an abstract, ambient section of some sort. With I Can See Forever, this abstract conclusion is an analogy to the idea of the infinite in the title. Roderick talks about getting there, to forever, but when he does and when he attempts to translate it, it ends up being the same cliché we’ve seen a million times before.

At the same time, he also mentions that maybe clichés like that are all that we have – they enable information relays and translation. The actual thing, infinity itself, is likely beyond our capacity as humans to elucidate.

I’m curious to hear more about your thoughts on time – in a general sense, as itself an object – and how you’re exploring it in the films?

Well, it all comes down to time really, doesn’t it? That’s what an altered state does: skews time. That’s how I always define them, in any case, as something that stretches or bends or speeds up time – something that distorts the ability to gauge time as we know it in this reality.

The films are written to be constantly referencing and challenging your relationship to time – manipulating it by putting the historicity of a time-based medium out-of-time. In Quickeners, one of the Quantum Humans afflicted with Human Atavism Syndrome says, “What’s the value of time that don’t end, anyways?” I don’t know, I just really like that line. It could sum up a lot of what these films are tapping into, in the human sense. What does anything mean to anyone if it lasts forever? Or what will it, if we get to a point where forever becomes a reality?

In a way these films allow us to think of time differently, because they’re constantly pulling us out of a particular abstract moment or narrative context.

That was always a goal: to create something that felt autonomous and succinct but also totally out of time. Something you couldn’t quite place and yet you were still convinced, to a certain extent, that somehow, at some point, may have taken place – or may take place.

What is Phase Shifting Index about?

It’s a seven-channel video installation with seven different fabricated groups that are all concoctions of disparate areas of subculture, dance, movement therapy, music, spirituality — existing in their own worlds. Each group is engaged in some type of embodied corporeal practice and presented on the media from the era they appear to come from — the late-1960s to the mid-1990s, from 16mm to VHS to Hi-8. The worlds they inhabit are related to the past films, with recurring references to the “Quantification,” “machineDNA,” “The Unit,” and many of these other ideas. At its core, the work explores the notion of inducing parallel realities through belief and movement.

The films play independently, simultaneously on loop and then, every 26 minutes, they start to unfold into chaos. They then land in a kind of trans-temporal sync with all subjects from all films doing the exact same choreographed dance routine.

The films all have narration, but it’s less urgent, less skeptical [compared with past films]. It’s been made and installed so that you can walk from one film to the other, and it doesn’t require digesting the complete narrative of each film necessarily.

Where did these various groups come from? In the early production notes I’ve seen, some are styled like 60s US military cadets, while others as if New Romantics?

They all came out of my notes and research from over the years — things I’ve wanted to see on screen, ideas I’ve had that hadn’t yet found a home. Maybe it’s a type of dance, or a certain fashion aesthetic — I’m constantly making notes about things I want to see or to combine at some point. But these are generally just aesthetics that I have mined, as each group has its own motivation and belief-system towards escape to a parallel reality that is not necessarily in sync with what that group would have been into in a historically accurate context.

Do subcultures create their own realities?

Any time you put your belief deep enough into something, to the point that it becomes your primary motivation, I see that as a type of self-styled reality.

In Phase Shifting Index, the narration is delivered from several hundred years in the future. The narrator is recording from a place where the discovery or the acknowledgement of parallel realities is itself reality.

Yes, in the work, the films are positioned as the first recorded evidence of the capacity to physically manifest a new reality through belief and movement.

Like the caves of Lascaux, which house some of the oldest-known paintings?

Yes, exactly that kind of idea. Whereas in the Trilogy, the narrator was skeptical of the information being presented, the narrator of Phase Shifting Index is reporting about the success of these groups in achieving their goals. He sounds almost as if he’s speaking to a dictaphone, noting to himself the descriptions of the disparate groups who have pioneered this phenomenon.

Parallel realities and multiverses are increasingly prevalent tropes in popular media. Is there a reason why you think these ideas are resonating with us, specific to this historical moment?

We’re in a time of crisis, and that always provokes searching for something beyond. We’re getting more and more information about quantum physics that is exposing areas of great uncertainty in what we’ve understood as empirical rationality. The revival of interest in psychedelics, and the dropping of stigmas around their experimentation, is coming together and overlapping with so many different areas. For example, whereas 20 years ago the majority of hip-hop was about keeping it real and maintaining a very grounded existence, I’ve noticed a really, really big shift to consciousness-expanding or psychedelic hip-hop music and lyrics and imagery. That’s just one example, but many things seem to be boiling over simultaneously in this regard.

The Age of Aquarius has finally arrived. In 032c Issue #36, food writer Michael Pollen spoke about his psychedelic adventures.

Psychedelics have totally become a mainstream topic, as attested by a very mainstream food writer now becoming an authority on them. I think the first time I really realized this was happening was when Lindsay Lohan started telling the world about her Ayahuasca trip, which is quite amazing.

For the more mainstream audience at the Pompidou, have you dialed down the cognitive dissonance or is that still at play in the work?

There’s a viewing platform in the Pompidou install, so that you enter from above the piece, because I wanted to have a place where you could really watch the sync moment in its cross-screen entirety. I find it quite compelling to just sit up there and watch them play out on their own, before the sync, together, without really being able to hear much distinguishable audio, only a murmur. It’s like how Bowie watches all those televisions at once in The Man Who Fell to Earth. So this feels like a kind of easier access point perhaps for a more mainstream audience. To enter from above and just take in this multi-screen landscape.

But once you start to watch the individual films, the cognitive dissonance aspect is definitely still there. This one is may be initially a bit easier on the brain as the narrator is friendlier in tone, but the films have equal or even more paradoxical and manipulative elements than before and the fact that there are seven playing simultaneously only amplifies that.

Credits

- Interview: William Alderwick