Barrikadenwetter: Image Acts of Insurgency with WOLFGANG SCHEPPE

|Phillip Pyle

The anarchist Mikhail Bakunin coined the term Barrikadenwetter in the newspaper Dresdner Zeitung whilst fighting alongside bourgeois revolutionaries, Richard Wagner and Gottfried Semper, in the Dresden May Uprising of 1849. Meaning literally “barricade weather,” Barrikadenwetter surfaced amid attempts to oust King Friedrich August II of Saxony as a term to describe the historical moment when a revolutionary subject emerges through collective action as an obstacle to the state’s rule.

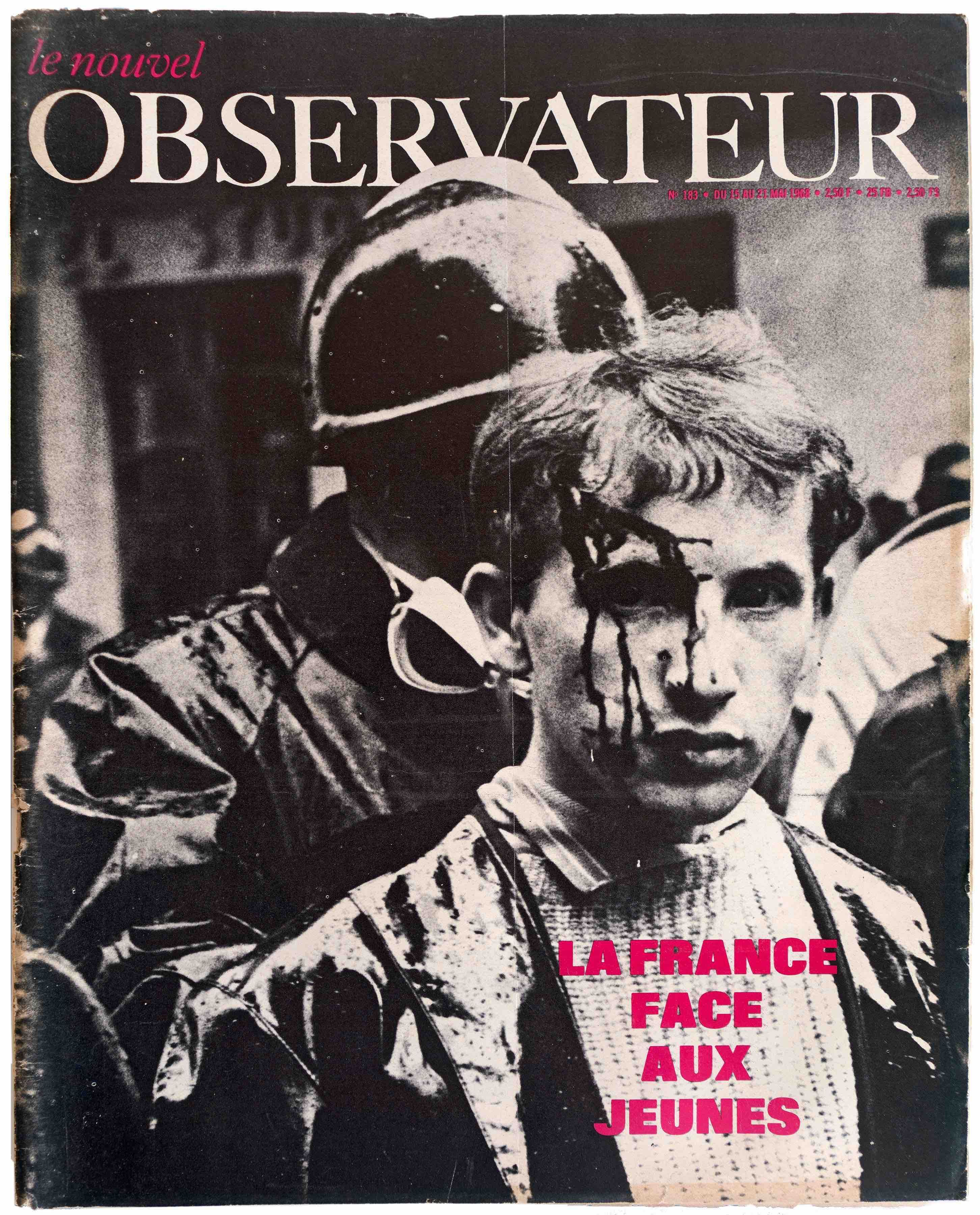

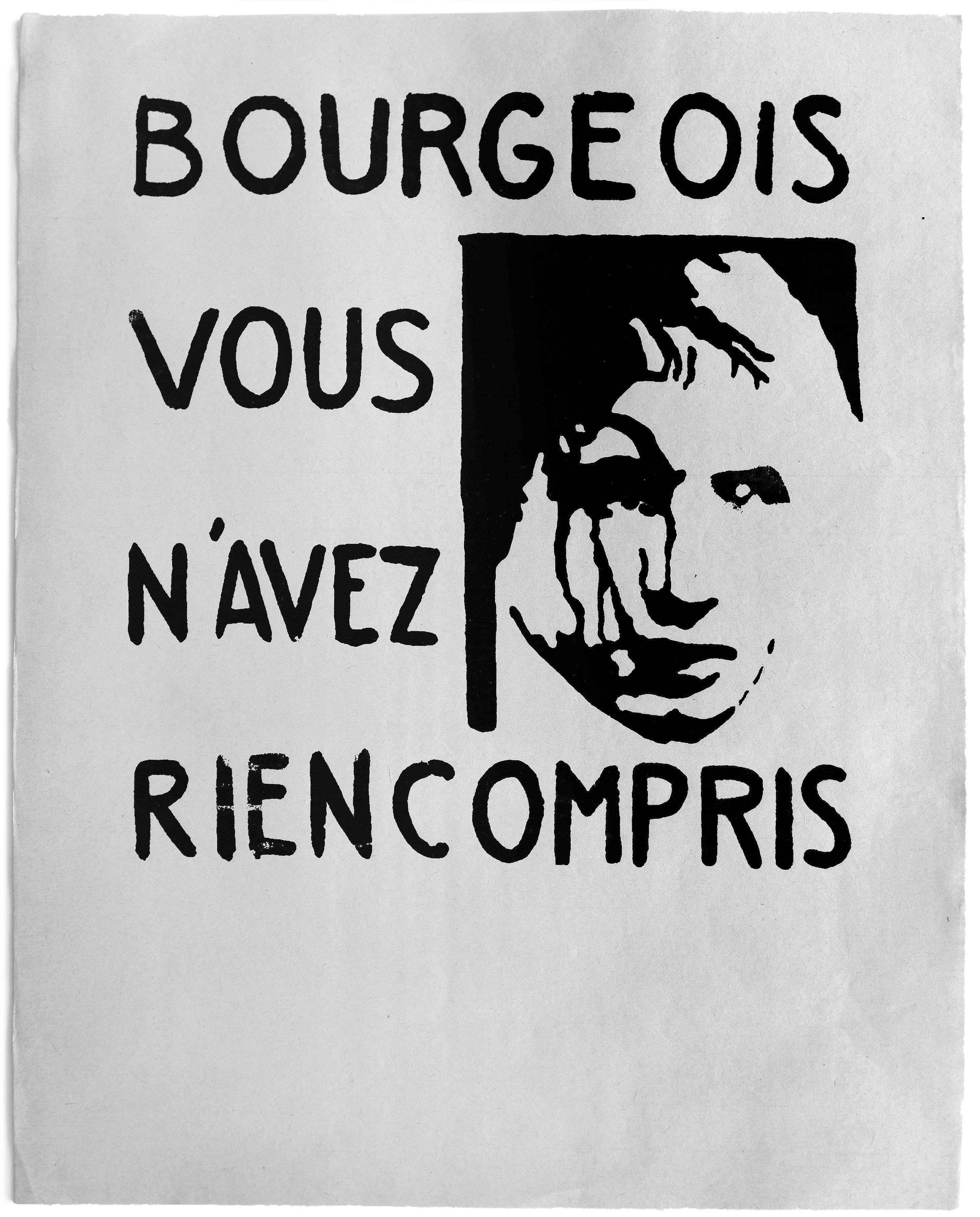

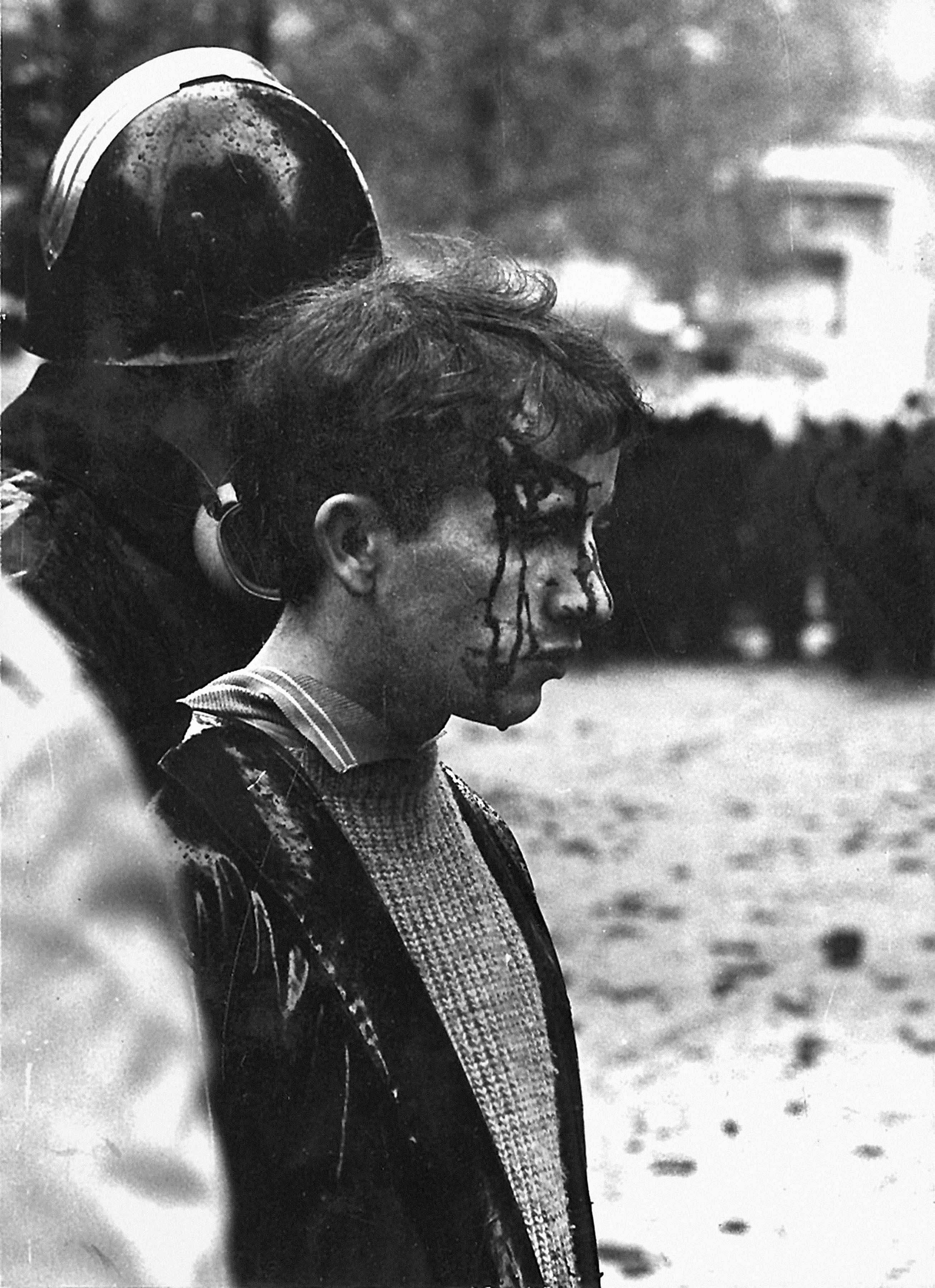

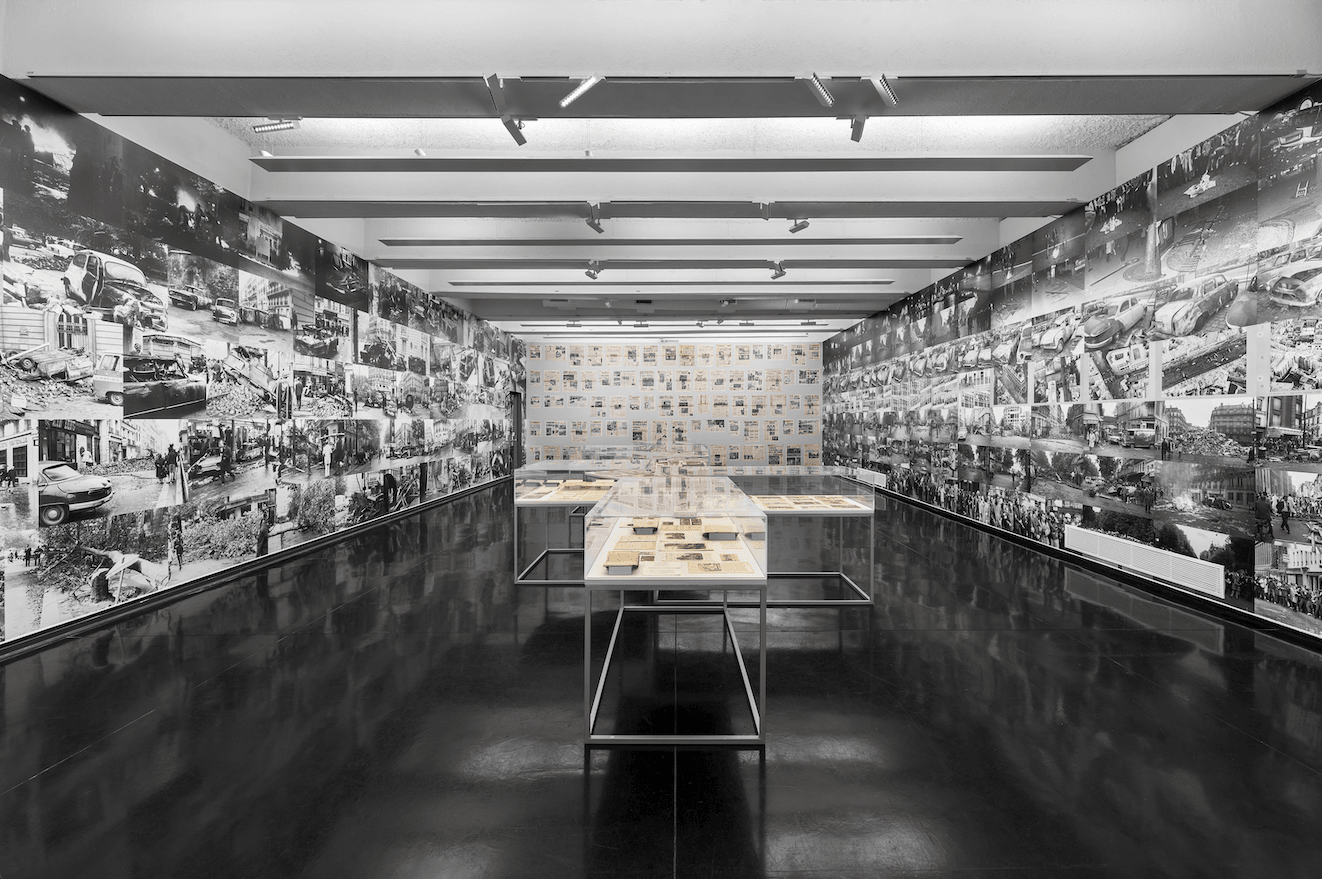

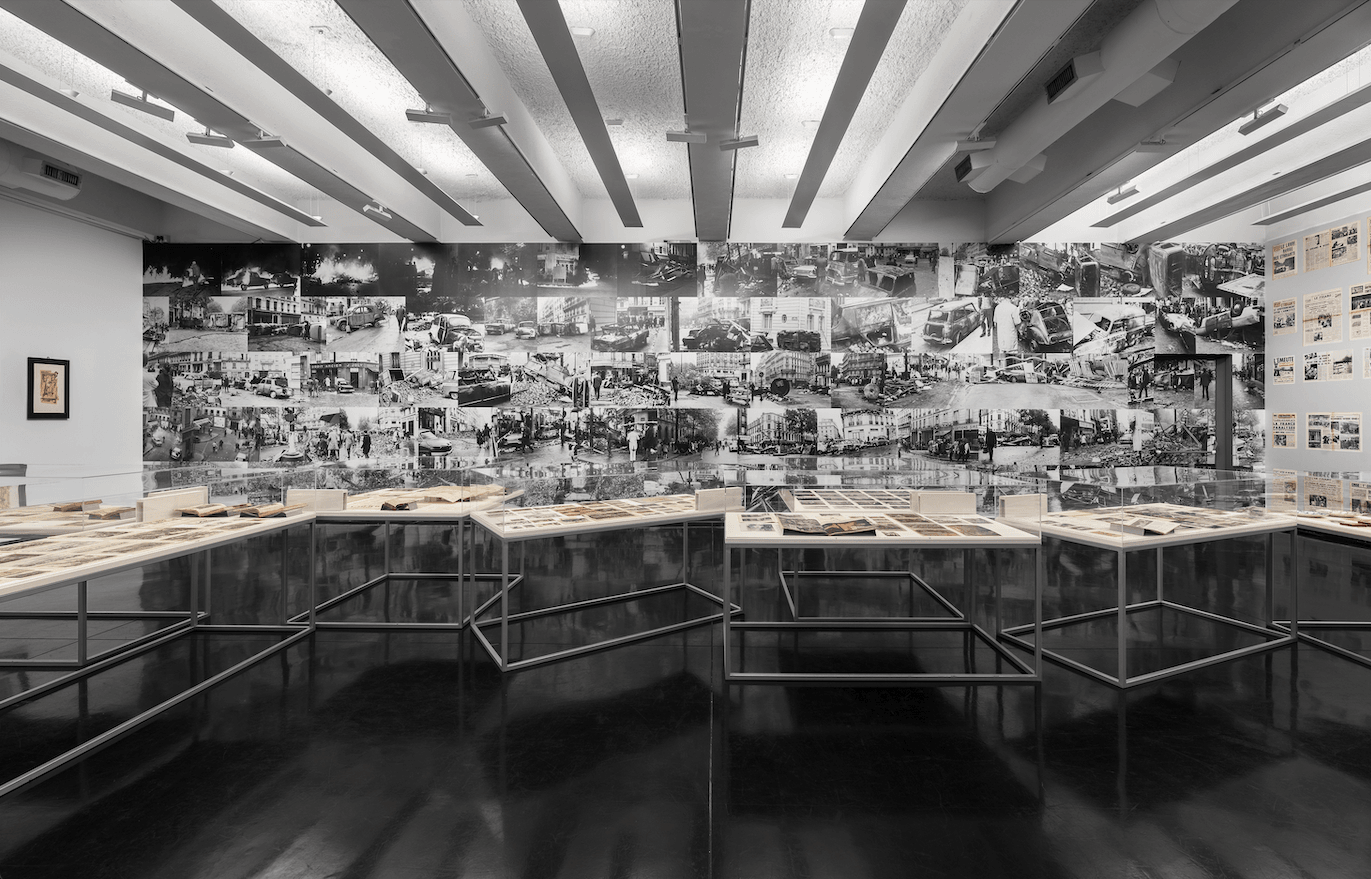

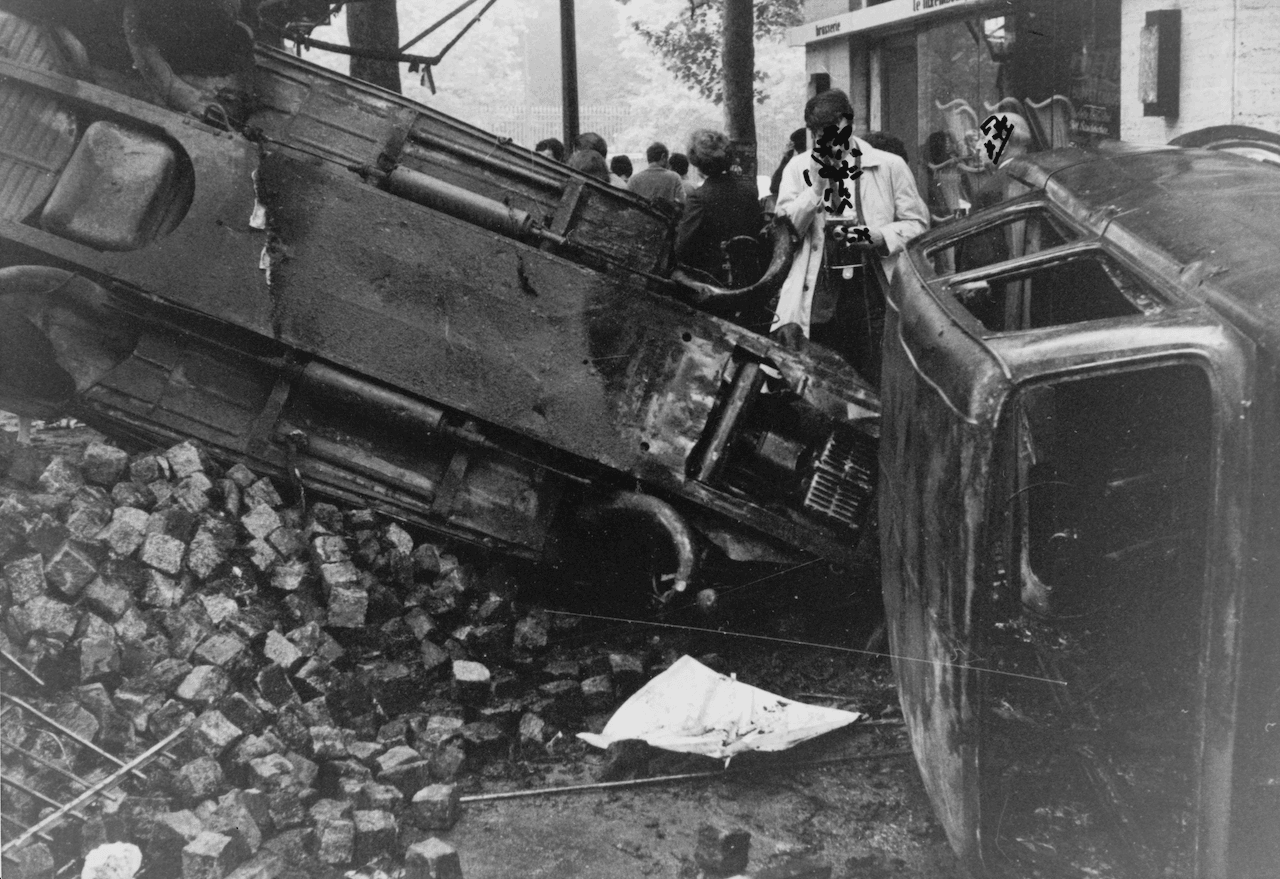

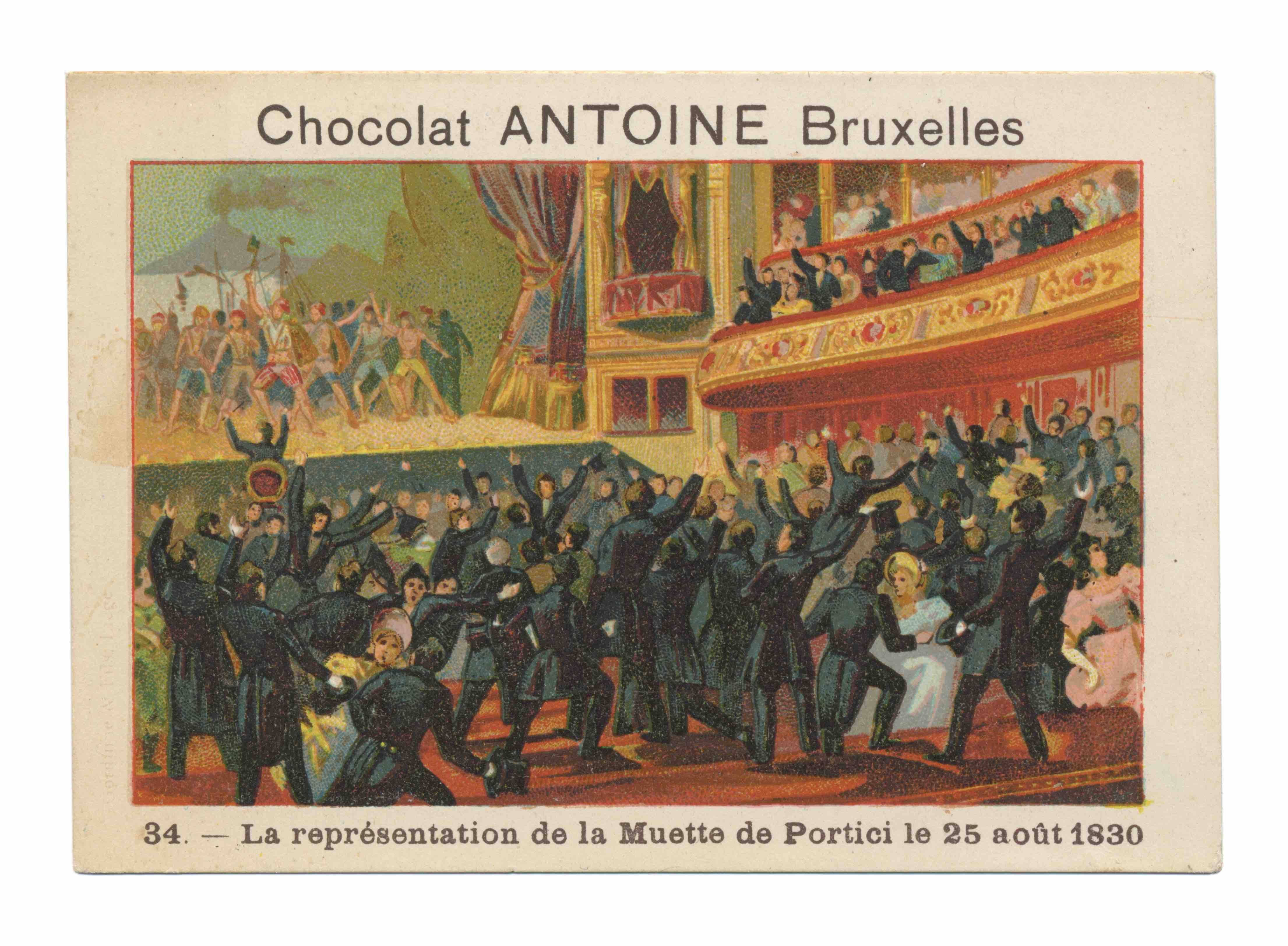

Taking inspiration from Bakunin’s term, the recently opened exhibition “Barrikadenwetter: Image Acts of Insurrection” at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Rome (MACRO) investigates the history of the barricade from the late Renaissance to today. The exhibition is curated by Wolfgang Scheppe, Bastiaan van der Velden, Sara Codutti, and Eleonora Sovrani of the Arsenale Institute in Venice, an organization dedicated to researching the politics of representation and societal use of images. The show divides images from the May 1968 revolts in Paris—along with dozens of other materials documenting the history, iconography, and symbolic meaning of the barricade—into three points of view: that of the rioters, of the media, and of the state (aka the police). These POVs represent what Scheppe describes as three different deictic image acts. Taking inspiration from philosopher J.L. Austin’s theory of speech acts, which stipulates that language has the ability to perform or provoke action, Scheppe’s theory of the image act suggests that images, more so than words, have the unique capacity to incite real action.

In September, Phillip Pyle spoke with philosopher and curator Wolfgang Scheppe around the opening of “Barrikadenwetter: Image Acts of Insurrection” at MACRO. Scheppe will be joined by Bastiaan van der Velden and co-founder of NERO Editions, Lorenzo Gigotti, on December 1 at MACRO for a discussion around the exhibition, which is on view through February 18, 2024.

PHILLIP PYLE: The archival approach to “Barrikadenwetter” reminds me of Georges Didi-Huberman’s work on “uprising” gestures. He posits that images and gestures act dialectically in “conflicts, antagonisms, agonies and affects” and that “people endlessly rise up.” This dialectical entanglement haunts many of the barricade images you’ve selected for this exhibition. Can you speak to the resonances between barricade images from different historical events, and how these dis/similarities rely on strategies of visual politics?

WOLFGANG SCHEPPE: I’m neither convinced barricade building is a teleologically endless ahistorical cycle nor that it is an anthropological constant in the nature of conflict. Our research, very much in contrast to the interest in a timeless phenomenology, is devoted to the precise analysis of historical preconditions and conditions for the emergence of specific barricades in specific street clashes, the protagonists of which must be precisely distinguished. At the end of my essay “Taxonomy of the Barricade,” I instead explain the emergence of a totalitarian control by state power, which has already entered a stage of technological possibility that may end any form of insurgency the moment it occurs.

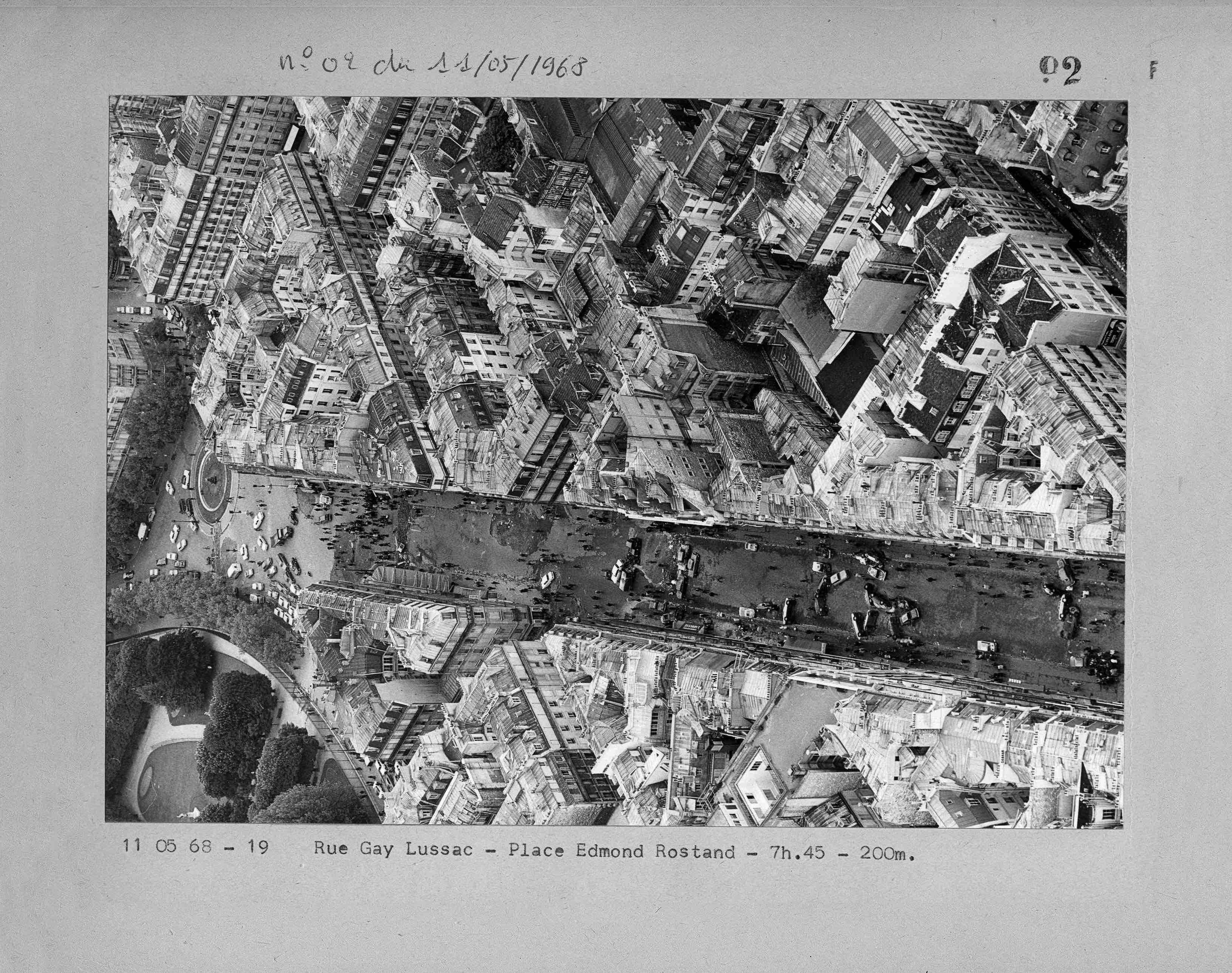

The pictorial order of a regime of surveillance applied during the last wide-ranging insurgence in Europe in May 1968 designates a critical moment in the development of governmental visualization strategies towards a totalitarian god’s perspective on the urban fabric. In the earlier Californian Watts riots of 1965, aerial surveillance by aircraft was initially exclusively only done by the media, a television station employing an ex-Vietnam helicopter pilot carrying a video cam. Among other characteristic typologies of authoritative monitoring aspects, the Archives de la Préfecture de police de Paris marked the historic beginning of the deployment of helicopter-based aerial photography as a means of governmental crowd control in a situation of escalating insurrection. The political will to gain an unobstructed view on any individual motion pattern leads to epistemically new technologies that combine observation with political governance and the use of force as recently manifested in the agency of drones and face recognition.

PP: The essay “Under Leviathan’s Eye” in your book Taxonomy of the Barricade was informed by the Paris revolts of May 1968, the event that this exhibition also hinges upon. In expanding this study to encompass a broader history of barricades, were there any unexpected findings?

WS: We arrived at new insights concerning the nature of image actions or deictic actions, as I would say. Those concerning the characteristic transitions in the iconography of the barricade after 1830, and at the recognition of the significance of the barricade’s obsolescence in terms of military strategy for the unfolding of its metaphorical power as expressed in the art of the early 20th century avant-garde. In most historical cases, the barricade as an obstacle proves to be only transitional, intended to impede and slow down the advance of a sovereign adversary, since this opponent, as the epitome of hegemonic power, usually retains the upper hand militarily. Advances in light mobile artillery gradually rendered barricades useless, at least as a strategic instrument. But at the same moments, their symbolic meaning appears with unexpected significance - with repercussions right up to the present day.

PP: What was the process for choosing what events, images, and narratives to connect with Paris? What’s the significance of this exhibition taking place in Rome?

WS: The performative motif of the barricade developed in Paris. It was initiated by the Holy League (La Sainte Ligue) with the Day of the Barricades on May 12, 1588 during the French Wars of Religion. It continued with the so-called Fronde, which culminated in the Parisian Barricade Battles in August 1648. Two hundred years later it spread across the world as a method of urban rioting in multiple conflicts of the 19th century. Beside Paris, Rome is the only major city that saw serious barricade building in both 1848 and 1968.

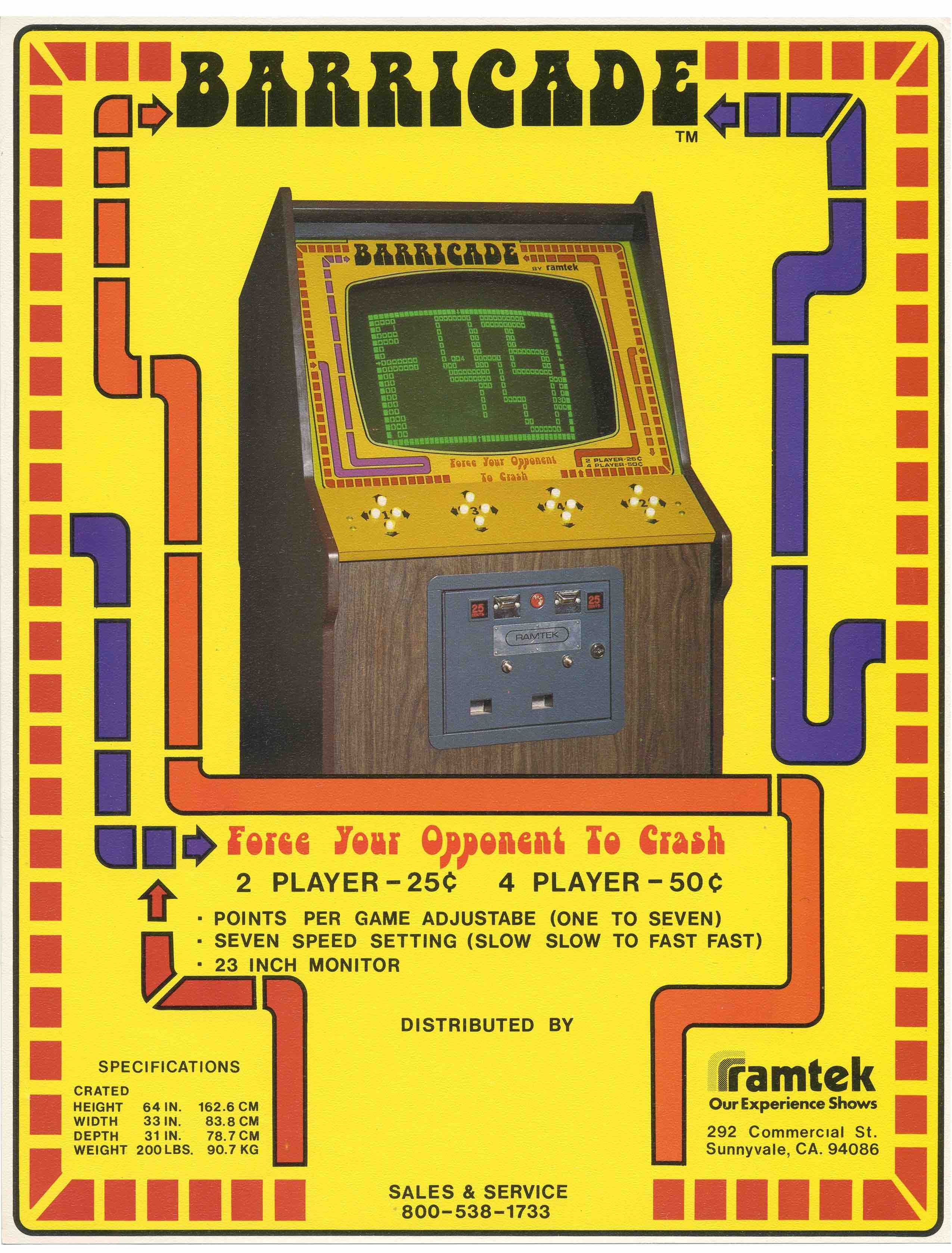

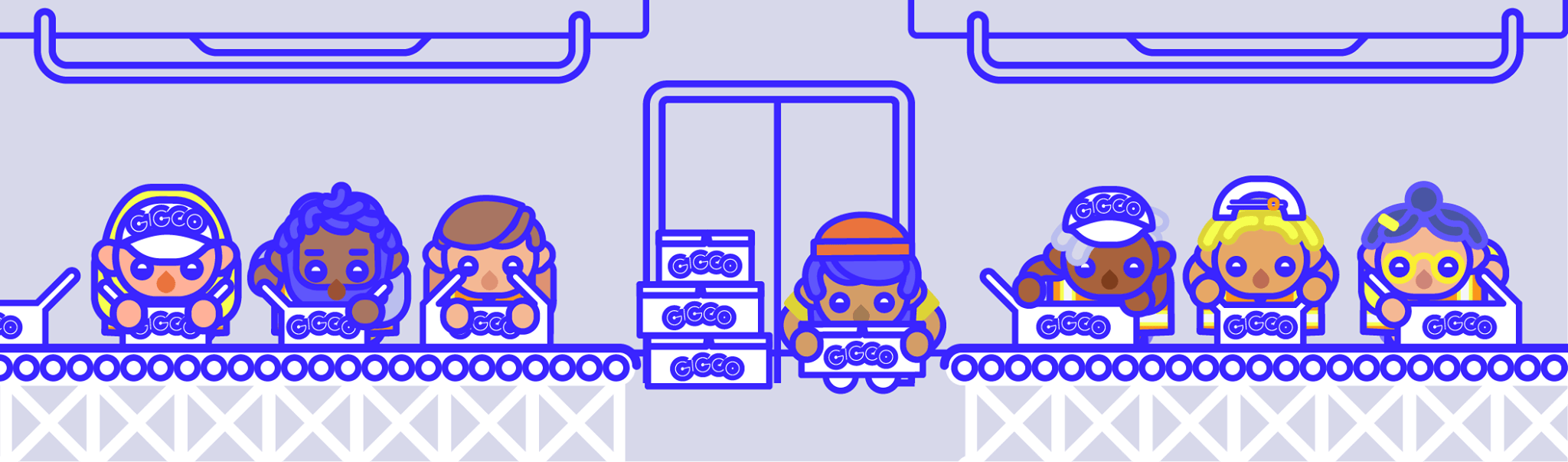

PP: The exhibition includes popular visual culture representations of barricades, including the 1976 arcade game Barricade—which was an early example of the “snake” videogame genre. What’s the importance of this pop culture element? Why did you choose to include this?

WS: The performative power in the metaphor of the barricade lies in the fact that, for the ruling class, its erection represents the sudden and spontaneous emergence of unity among a serious mass of the people who have taken action. The apparition of this spectre must seem frightening to any government. The pride in this sole tool of an otherwise inferior class made it a powerful popular symbol in all cultural spheres, be it games and entertainment.

PP: Many barricades have a readymade quality to them. Is there any relation between them and DADA and surrealism?

WS: In many ways, DADA drew its strongest visual inspiration from the logical structure of the barricade. In the context of the November Revolution, several members of the Berlin DADA group were involved in the armed struggles of the Spartacus uprising from January 5 to 12, 1919, such as Raoul Hausmann, [artist] Hannah Höch’s husband. He wrote, “Spartacus was on the streets, everywhere, and Dada was stirring in shaken Berlin.”

PP: You argue that barricades had a great influence on early 20th century avant-gardes but only use Hannah Höch’s collage as the single artistic demonstration of this. What is the theoretical commonality between avant-garde techniques and the barricade? And why did you only use a single artwork in the exhibition?

WS: The logical structure shared by both early avant-garde movements and barricades is this: Elements from the inventory of society are being abused to overcome the latter. In visual arts, the collage is evidently equal to the structure of the barricade. But the abusive composition of random elements and heterogeneous fragments taken from the inventory of bourgeois society in action against it (as in the logic of the barricade) can be found in all genres of art: the Situationist détournement, the cut-up technique of the Beat Generation, and Brecht’s Verfremdungseffekt in literature; the assemblage in sculpture as seen in the oeuvre of Vladimir Tatlin and Kurt Schwitters; the pastiche and the sample in music, from Erik Satie, Charles Ives, Walter Ruttmann to hip-hop; Constructivism and Deconstructivism in architecture, for example in the work of El Lissitzky; montage in film, as described by Sergei Eisenstein.

The Dadaists in Berlin–that started it all–and Höch herself were involved in the November Uprising in 1919. Höch saw the barricades in Berlin that were put together from random materials found in the urban fabric, most famously the paper rolls of the Mosse-newspaper printing facilities. Her collages are clearly hinting towards this logical structure: To divert and detour elements that originate from the very society you are criticizing. To give an initial indication of this fundamental art-historical theorem, we use an outstanding collage by Hannah Höch to illustrate this thesis. However, we are working on a publication and subsequent exhibition that will provide ample evidence of this new concept across all art genres.

PP: While the relationship between totalitarian perspective/control and aerial photography of barricades feels rather intuitive, something less clear is happening in the personal photographs of barricades included in the exhibition. I’m thinking, for instance, of the snapshots of women smiling as they pose with a rock barricade. How might quotidian and personal representations of these structures shift our understanding of barricades?

WS: The examples you point to are Sebaldian in nature. We will never find out what inspirations of utopian poetry individuals draw from their experiences with barricades. But we became aware of the existence of such sentiments at the opening in Rome. Several older visitors were quite emotional when they told us about the days they were involved in the street fights in either Paris or Rome. They tried to find themselves in the pictures. Even in the days of the Commune in Paris in 1871, posing in front of barricades, some of which were erected just for the photo oppurtunity, was a widespread occurence. After the suppression, the state authorities used these portraits as evidence against those portrayed.

PP: You begin “Under Leviathan’s Eye” by suggesting that the state’s will to supervise society has reified itself in the instrument of the armed drone. With the drone, the eye of the state becomes an eye that sees and acts, that observes and kills. The absolute power this grants to the sovereign mimics the power that the sovereign holds over human life (and death) in states of exception and emergency. If the armed drone is now ubiquitous does that mean the state of exception, too, is possible everywhere, at all times?

WS: As Carl Schmitt, the German political theorist and Nazi law professor, so accurately explained in his cynical precision: Sovereignty in general is defined as the power to initiate a state of exception. Every legal provision implies its overcoming in emergency law as normality in its application. The law must express the respective will of the state authority and is made appropriate to this at all and any times. No bourgeois legal philosopher has ever come so close to the truth of all government that makes use of the authority of the law.

PP: When thinking of barricades, aerial photography, surveillance, and armed drones, I cannot help but think of the works of contemporary artists and theorists such as Trevor Paglen and Hito Steyerl. Can art alight methods for resisting oppressive optic regimes?

WS: I’m afraid that’s a false hope. I don’t believe that the overwhelming will to conduct one’s political action within aesthetics and to make it succeed on the art market replaces a precise and persistent research in order to achieve positive knowledge. In these days of brutalization, there is little else left but to spread seriously acquired knowledge.

Credits

- Text: Phillip Pyle

Related Content

HISTORY OF THE WORLD: A POEM BY PETER DE POTTER

ALVIN BALTROP and the Unofficial History of Cruising on Manhattan’s West Side Piers

Architecture of Resistance: The Barricades of Kiev

Mining a Counter-History from the Past: WILLIAM S. BURROUGHS and Subcultures in Kansas

Monstrous Thoughts: Philosopher EUGENE THACKER on the “New Golden Age of Horror”

Gamifying Resistance: SPEKWORK’s Political Video Games

BIFO BERARDI on Political Impotence and the Rise of Global Silicon Valley

An Artist Reports on the Future of Europe