ANCUTA SARCA Reshapes Deconstructed Sneakers

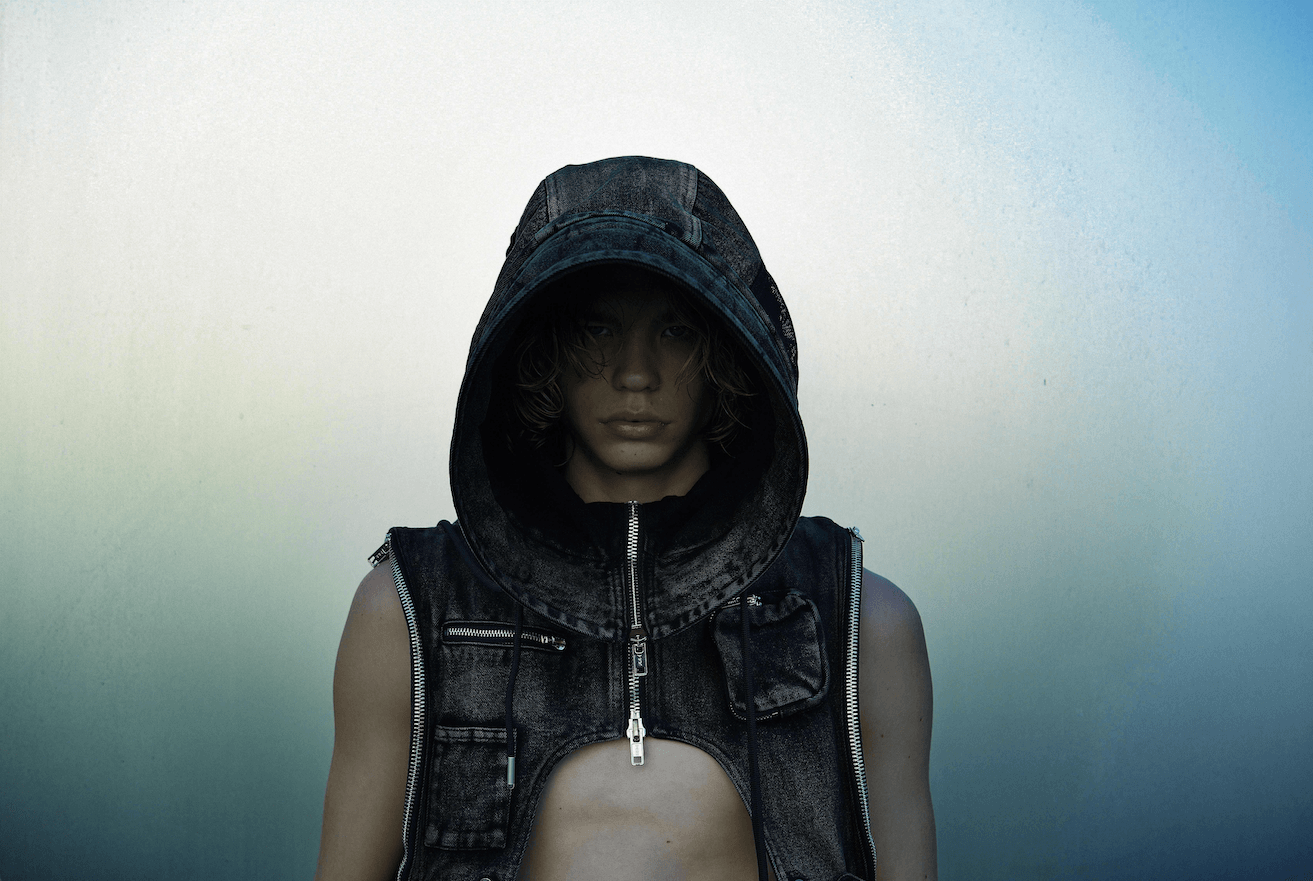

The surrealist designer Ancuta Sarca deconstructs old gym shoes and transforms them into new forms. With her use of vibrant colors, striking graphics, and elegant juxtapositions between casual sneakers and graceful heel structures, Sarca’s shoes have become a sensation, boasting a distinctive and instantly recognizable style.

What started as an up-cycling endeavor is now venerated on platforms such as SSENSE, Browns, and LN-CC, and being worn by the glitterati of Generation Z, including Rihanna, Bella Hadid, and Rosalia. Here, we talked to Sarca about her business plans, inspiration, and Romanian upbringing.

ALMA LEANDRA: Looking at your designs, I’m reminded of Meret Oppenheim’s Object (1936). Though not usable as a coffee cup, as it’s covered in fur, it’s still recognized as one. You reconstruct sports shoes and bring them into a new form that does not fulfill their original function. But they still don’t lose their recognizability. Are there any philosophers or artists that are important for your practice?

ANCUTA SARCA: Drawing continuous inspiration from artists such as Duchamp, I incorporate readymade objects into my collections, as I've always been drawn to the idea of seeing familiarity in an object. When people see my shoes—such as a pair of Nikes from the 70s now wearable as a heel in 2023—they encounter a sense of recognition intertwined with novelty. There’s a harmonic balance within the clash of opposites, such as between old vintage leather and modern sports shoes, and I have always sought out this interplay of the past and future.

In fact, the artistic principle of the readymade has always been a central aspect of my work, even during my time at university. I wanted to adopt a conscious approach by utilizing materials that didn’t require extensive collection development. This way, we keep the supply chain small and create bespoke products. I started my Bachelor and Master in garments but have been an avid shoe collector since an early age. At the core, I customized them to wear them personally. I never planned to start a brand, but friends and others wanted to buy them, leading to its organic growth.

AL: Are you trying to create a new narrative through deconstruction and reconstruction?

AS: I'm focused on forging hybrids, mixing, and combining antithetical products. I am using juxtapositions, such as feminine and masculine, or vintage and modern, to deconstruct and reconstruct.

AL: Do you find yourself drawn more towards deconstruction or construction?

AS: It’s a symbiosis of both. You must deconstruct to construct. What thrills me is that the exact outcome is unpredictable during the deconstruction phase—it’s challenging getting over that mental hurdle. We've created a new line where we use only deadstock textiles, such as garments or end-of-roll fabrics from textile warehouses, which slips more into the category of construction. Most exciting is combining them together.

AL: It's oddly comforting to see a heel in the form of a sports shoe because it makes it seem like it’s more comfortable to walk in. Did it initially feel wrong to tear apart sneakers and use them in the sport-estranged context of heels?

AS: It’s scary and pushes you to be more careful when you don't have a budget to keep buying if something goes wrong. But I let myself be driven by the excitement of what they will become. It's not like I was using vintage Chanel or rare designer pieces. I was using Nikes, something that you could find on eBay very easily. So, it's not lost if you destroy it.

AL: Your heels can also be seen as an homage to pop culture.

AS: While our exterior may give the impression of conforming to pop culture, our internal processes defy convention. The effort of sourcing is so slow compared to fast or luxury fashion. I acquire secondhand Nike sneakers, which we then transform through binding, deconstruction, and cleaning in London. I say “we” but really, it’s mostly just myself [laughs]. The revamped sneakers then travel to Italy, where they get stitched and assembled into heels. Everything else that goes into the shoes is pulled from deadstock.

AL: What do you think about pop icons, such as Rihanna, endorsing your work? Their association brings greater visibility yet often leads to fast fashion labels ripping off your designs.

AS: As soon as you put your shoes online for sale, anyone can buy them, there's no control over it. Things can escalate without you even realizing it. Without any marketing strategy, I was approached by people, mostly stylists and others that I admire, and I saw this as building relationships and helping my business grow.

AL: Many brands have authentication tags. Do you have a similar mechanism to prove this is a real or fake Ancuta Sarca?

AS: We're working on it. My trademark is registered worldwide. Naturally, that didn't stop fakes from circulating. I am trying to communicate with authorized stockists to exclusively sell my products. As a small brand, there are numerous things that still require implementation.

AL: What you do is classified as fashion design but can also be considered an artistic practice. Where do you see yourself in these two realms?

AS: I went to an art high school before starting at fashion university. I was always more drawn to artistry than to business and marketing aspects. My primary focus lies in design and creating a story, rather than creating something to sell. Commercial success is merely a byproduct. The initial idea was to create something innovative and modern, something that people haven't seen. Something that draws your attention and makes you want to wear it. I design as an artist. I do all my research. I think a lot. I draw. And I try to visualize more than pondering about sales strategies. This comes later. Growing up working class in Romania, it pushed me to not just make shoes that no one is going to buy in the store. It needs to have practicality, and I wanted to keep my feet on the ground.

AL: The art high school was in your hometown, Negresti Oas?

AS: It was the art high school Aurel Popp in the neighboring town, Satu Mare. I moved there when I was 14 to study in the art-specialized high school. We would do ceramics, sculpting, painting, and music, but I was only interested in the visual arts. It was remarkable. The school comprised a community of aspiring artists, in an unprecedented level of freedom compared to every other school in the area or throughout Romania as a whole. Art high schools are spaces where you can build your personality and broaden your horizon a lot faster.

AL: Did you move there alone or with your parents?

AS: One of my teachers managed to persuade my parents to let me attend this school alone. So, I’d travel there every Monday and return on Fridays. I was living in a dorm akin to a student’s residence.

AL: How has growing up in a small town in post-communist Romania influenced your perception of capitalism and production cycles?

AS: Growing up in the 1990s and early 2000s, right after communism fell, was a challenging time for my parents and grandparents. They struggled to adapt. My parents dedicated their life to working abroad in construction and cleaning. During this time, I was left in the care of my grandparents, my older sister, and brother. They didn’t have the same educational opportunities we had, but wanted my brother, sister, and myself to have a real education. So, all they did was work. That instilled a preset work ethic in me and the importance of excelling in my work. When I started working in fashion, I wanted to approach the production process and manufacturers differently. I witnessed the exploitation of the factory workers in the fashion industry and wanted more control over that aspect of my business. That’s why we produce in Italy and personally visit the factories on a regular basis.

AL: How did you end up in London?

AS: During my master’s program in Womenswear at the University of Art and Design of Cluj-Napoca, Romania, I undertook internships in London, one of which was with Meadham Kirchhoff. London impressed me so much that I wanted to return. I saw an opportunity to grow and develop myself and develop my cultural background.

AL: Your shoes deal a lot with feminine and masculine energy and to me suggest empowering women. How did growing up in a small-town shape your view on power dynamics between men and women?

AS: Our upbringing was very strict and quite religious. I speculate that this is why I went into arts. I saw some sort of freedom in creating and transforming my clothes into something that my mother wouldn’t let me wear [laughs]. The power dynamics between men and women were clearly unjust. That's why I always looked at how Western societies are structured and took all the opportunities at university to do internships abroad. My parents set a good example for us. We didn't really see that dynamic in the family, but the older the entourage, the more conservative the power dynamics were. She is just an extremely dedicated and caring mom and working hard and not doing much for herself. Ever. It was always us or the family first. I'm still questioning how this might have impacted me because I'm very career driven, but for her, it is primarily about her kids and being a nurturing mom.

Credits

- Text: ALMA LEANDRA

Related Content

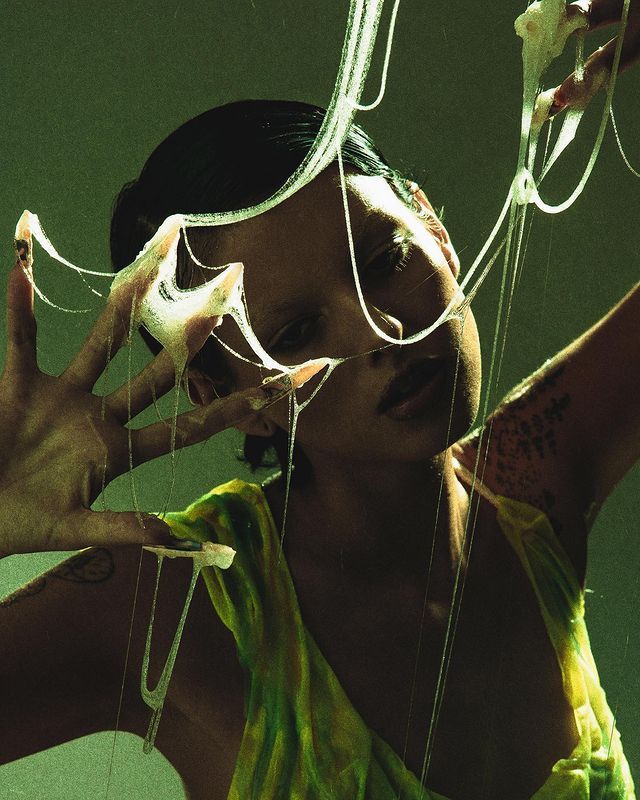

Digital Alchemies Resurrect the Dead

German Denim Dreams: LUIS DOBBELGARTEN's No/Faith Studios

Head Over Heels: AVAVAV

Notes From Underground: Slime Fetish

Slash’n’Lace: Welcome to the Couture of OTTOLINGER

Ukrainian Designer YULIA YEFIMTCHUK’s Extremely Soviet Vision of Post-Soviet Youth

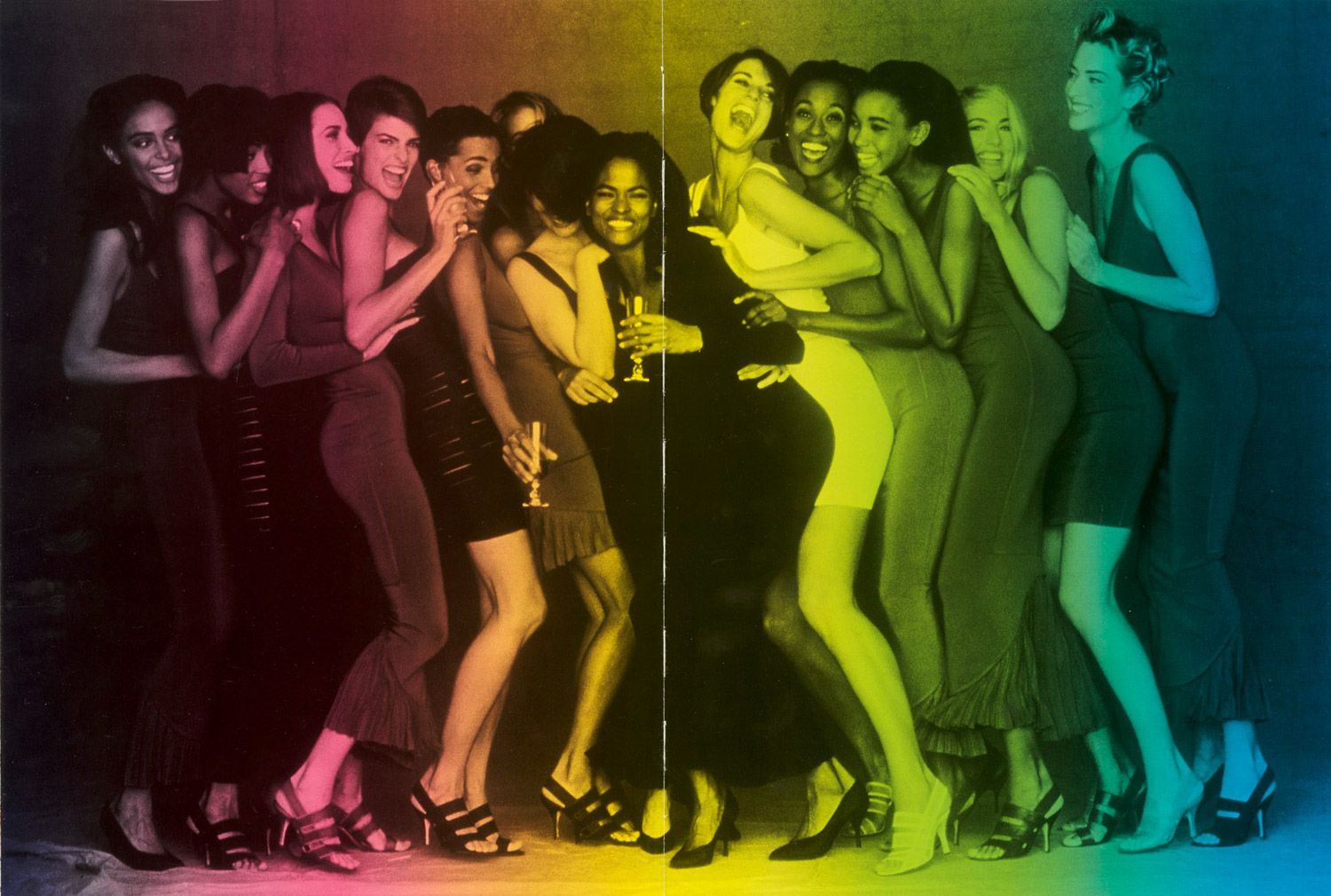

AZZEDINE ALAÏA Loves Animals & Women

Texting with HERON PRESTON Before the Presentation of His First Collection