LEE “SCRATCH” PERRY

|Arno Frank

UNESCO DECLARED REGGAE AN INTANGIBLE CULTURAL HERITAGE. NO OTHER ARTIST EMBODIED ITS HISTORY BETTER THAN LEE “SCRATCH” PERRY, THE LATE FATHER OF DUB.

The woman behind the wheel has a joint in her right hand and a smartphone in her left, white wine in her blood, and everything under control. Now and then the Hyundai veers onto the shoulder, but Mireille, 59, just sighs and jerks the steering wheel back into place. The SUV wobbles but doesn’t tip over; we keep going down the winding coastal road, the Caribbean Sea in the moonlight on one side, and the dense forest, in total darkness, on the other.

The imposed curfew in the district doesn’t apply to the passengers in this car. They’re looking for a club, a restaurant, a place where night can turn into day. “My husband doesn’t get in small cars anymore,” Mireille shouts over her shoulder. “It’s too dangerous here on the island!” Then, turning to her right: “Right, Lee? Do you hear me? Lilli? Lilliput?” Rainford Hugh Perry, known as Lee “Scratch” Perry, doesn’t look up, even when she hits the brakes. He’s deep in thought, absorbed by the notes he’s relentlessly typing into his smartphone: Rainstorms swords rainboards swords dancehalls dooms lucefifer rooms dancewalls … rooms Adam Jamaica adambammbed adami bamb.

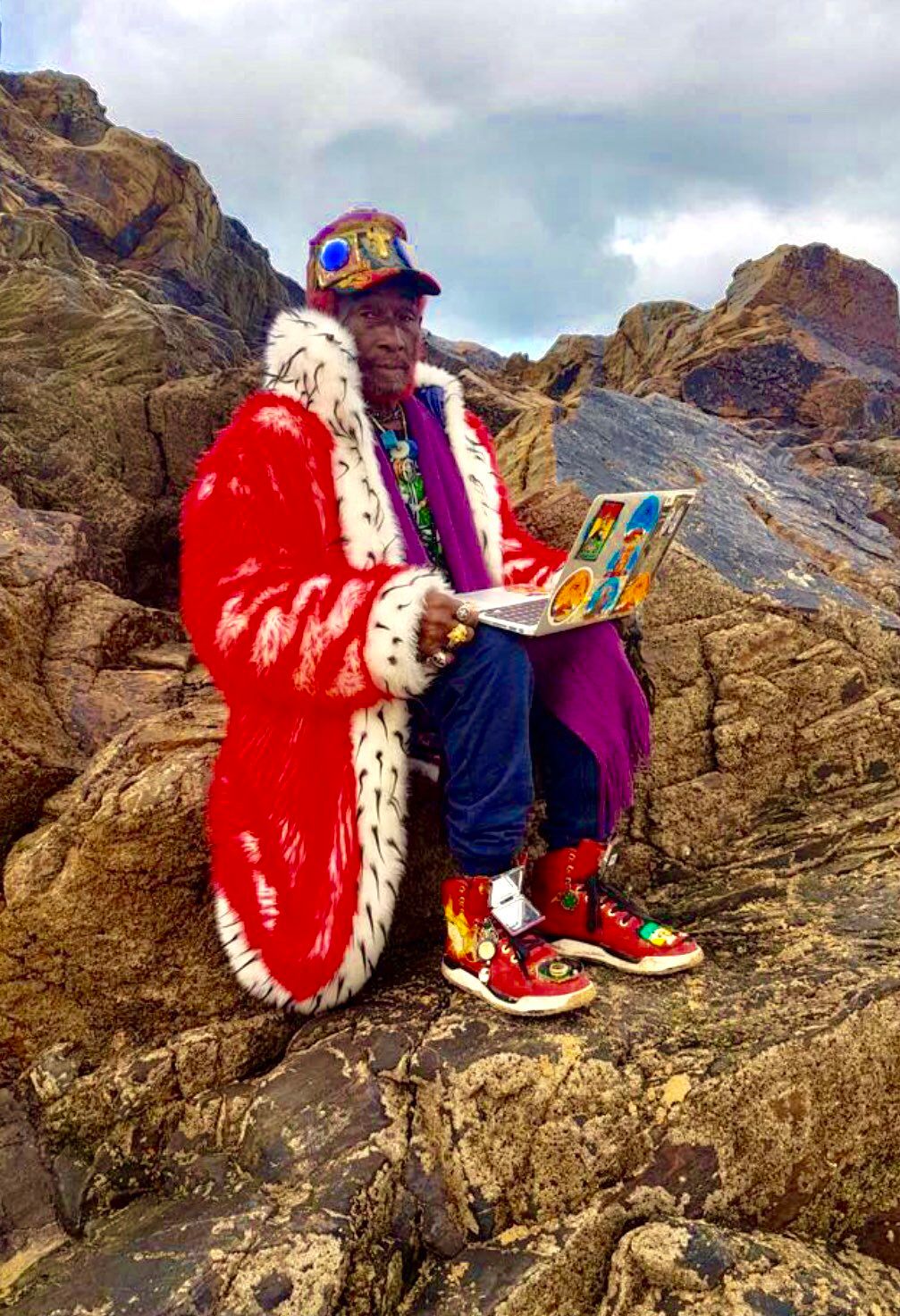

Underlit by his glowing screen is Perry’s baseball cap, decorated with an assemblage of butterflies, mirrors, shells, pebbles, feathers, and various shiny objects. He’s also known to get creative with his shoes – usually lightweight boots, though tonight he’s wearing plastic slippers with red socks, a t-shirt featuring Son Goku (hero of the Dragon Ball manga series), and a tracksuit in the Jamaican national colors. His hair and beard are dyed red.

Perry has 83 years under his belt, and has been married to Mireille for 27 of them. By now he knows she’s got the car under control. He’s immortal anyway, he likes to say – like the clouds, or a melody.

Anyone with a hit song is immortal in pop music, but most of Perry’s hits have been productions for other artists. He’s been on the charts under his own name a few times, but remains relatively unknown to the mainstream. His most successful single was “Return of Django,” a short instrumental piece recorded with The Upsetters, his former studio band. It made number five on the UK Singles Chart, back in 1969. Perry’s legendary status, particularly among musicians, is transcendent, not commercial: he’s one of the very few true “musician’s musicians” out there.

In the 1970s, pop stars – think Robert Palmer, Paul and Linda McCartney – made pilgrimages to his Black Ark studio in Kingston. In 1977, Perry produced the single “Complete Control” for The Clash in London; on the other side of the Atlantic, he was the inspiration for Afrika Bambaataa and the late 1970s South Bronx scene that birthed hip-hop itself. Jay-Z, The Prodigy, and Primal Scream have sampled his work. The Beastie Boys’ 1997 “Dr. Lee, PhD” is all about Perry, who has a writing credit and sang on the track. Keith Richards has called him a “shaman” and the “Salvador Dalí of music,” and compared his gift to Phil Spector’s: an ability not only to hear “sounds that come from nowhere else,” but to translate them to other musicians. He is the Aristotelian “unmoved mover” of modern music: the origin of all things, pure activity and source.

Perry also helped birth reggae and its psychedelic sibling, dub, boiling down the rhythm to its fundamental components – drums and bass, reverb and echo and space. Together with King Tubby, he laid the foundations for every genre of modern dance music: techno, house, drum and bass, dubstep. Over hollowed out beats, he has sung his own praises and defamed his rivals in improvised chanting – a precursor to rap called “toasting.” Embracing everyday sounds over classical instrumentation, he introduced bricolage to pop music. Through his reworked “versions” of existing songs, he elevated the remix to a cultural form. Since then, no composition has ever been finite: each one can be the source of endless variations of itself. Alongside only a handful of other pioneers, he is a representative of the Paleolithic Age of Pop, the influential spirit of which continues to wander, leaving its mark on every new musical field.

On short notice, he cancels a meeting in Kingston via WhatsApp voice message. There’s “too much jubilation and hustle and bustle” there, he says. In 2018 UNESCO declared reggae an Intangible Cultural Heritage, to the pride of the nation. The Jamaican capital was where it all began, but the original roots reggae has since been deposed in Kingston, ousted from the soundscape of the city by the mobile sound systems of dancehall, and consigned to history.

There’s a small museum for Peter Tosh in Kingston, and a stately one for Bob Marley. The “One Love Tour” starts at $40 a day and includes Marley’s recording studio and home, where “the original rooms have been kept as they were” – minus the life-sized hologram and the gift shops. Photography is strictly prohibited. The museum is Jamaica’s answer to Disneyland – Marleyland.

An authentic place of worship still exists, however, and it’s only 15 minutes away by taxi. The Kingston suburb of Washington Gardens was a middle-class residential neighborhood when Perry moved his studio there in the early 1970s, before the political upheaval and economic decline of the 1980s. The smell of the nearby garbage dump blows in on the breeze. Dogs doze in the shade of large trees and goats leashed to old truck tires graze.

The building at 5 Cardiff Crescent is not accessible to the public. Its iron gate is adorned with a portrait of the political activist Marcus Garvey, guardian saint. Living in what remains of the compound is Poppa-Son, 63, one of Perry’s younger brothers – half resident, half guard, like a priest looking after a reliquary. He lives off of occasional road maintenance work, fruit from his garden, and entrance fees from the rare visitor wanting a tour.

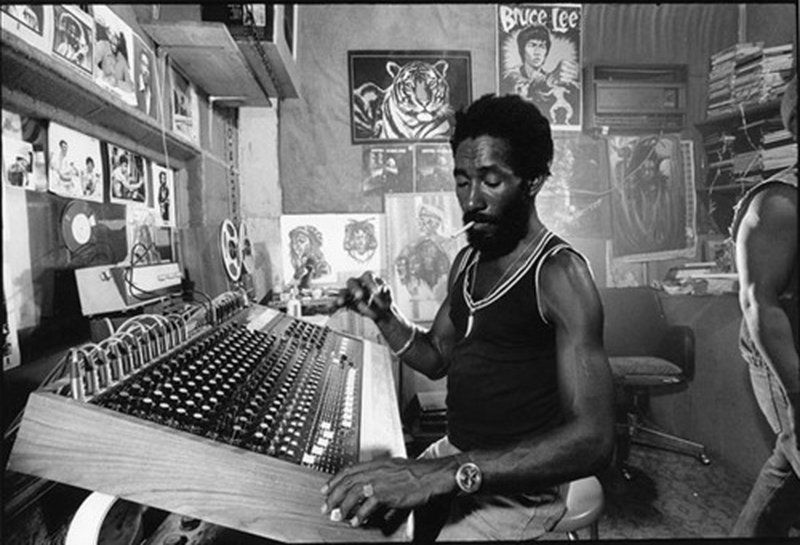

Behind the house, past the pigeons cooing in the crates on the roof, abandoned chicken cages, and dried up fish basins, are the ruins of the legendary Black Ark studio. Inside the soot-blackened box: old Red Stripe beer bottles, a tube television, a bicycle frame, and shards of glass in the ashes. Vegetation grows through the windows; once state-of-the-art equipment – an old mixer, a keyboard – sits in the corner, left to the elements.

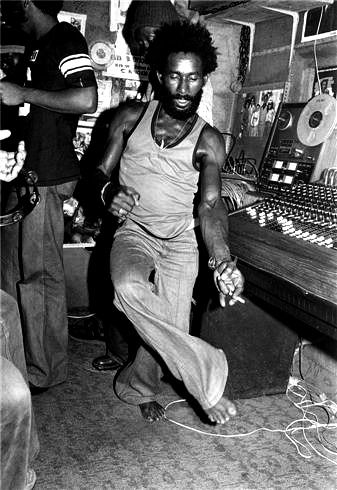

It was here that, in 1973, Perry started conducting his “experryments”: intuitive, improvised, unencumbered by musical convention. Playing music and smoking weed, he understood the studio itself to be an instrument, a being. He ritually blew smoke over the recorded tapes to immerse them in the “holy ordinations of ganja.” He covered this space in chicken wire to achieve a more rattling sound.

Bob Marley once rented out the studio, having turned up and asked Perry to show him the way to the stars. “He rang my bell and wanted to know if I could help him,” Perry eventually tells me. “And I could. Bob Marley lived in my house and I helped him. I gave him the reggae to get rid of the reggae. Bob Marley lived in my house and now his family is rich.” Perry’s relationship to Marley is complex – sometimes Marley’s a thief, at others a pirate, but he’s always a friend. A wall in the corridor reads “Bob Marley dead, Peter Tosh dead,” scrawled in black paint.

Inside the house, the concrete walls are painted from floor to ceiling, inscribed with words, covered with pages from magazines. The image of Haile Selassie – the last Emperor of Abyssinia, savior of the Rastafaris, and the person Perry understands himself to be a playful manifestation of – is everywhere. Conan the Barbarian, the Black Madonna, Aladdin, Bruce Lee, Princess Diana, and the Eye of Horus all make appearances. Alongside them are collages (of twigs, incense sticks, banknotes, candle wax, and old VHS tapes) and a quote from Victor Hugo: “Wind, waves, flames, trees, streams, rocks, everything lives! Everything is full of souls.”

Perry’s chaotic productivity took a toll on him eventually. He overspent himself with countless new “versions,” not just of his songs but of his own persona, alternately going by Inspector Gadget, Pipecock Jackxon, or Super Ape. He told journalists that he came from Sirius, millennia ago. He worshipped bananas, ran backward through the city, and received guests with a garden hose. He drove around with maggoty meat strapped to the hood of his car. People started to fear him, and he was even scared of himself. Perry types in his smartphone: You hello gritty hello New York City hello hello Kingston city hello Stonehenge hello revenge LOL venge how do I superhero hello super supermarket hello Sue hello black convertible.

When the Black Ark studio went up in flames in 1983, some called it the end of the roots reggae era. Others called it arson, and speculated about gang-related shakedowns, crossed wires, and the extent of Perry’s drug use. Poppa-Son was with his brother that morning. “Lee was trying to drive out the demons,” he says. “He lit a fire on a plate. It got out of control. We tried to put it out with buckets … It was an accident.”

After the fire, Perry left the Caribbean, eventually moving to Europe. He fell in with a bad crowd and, gradually, into oblivion. He lived as aimlessly through most of the 1980s as his music from the time suggests. It was Mireille Rüegg Campbell who finally saved him. A Swiss businesswoman who had worked as a dominatrix in Zurich and as a reggae record dealer in London, Mireille took the burned out star under her wing: “I want to be involved in everything you’re doing,” she told Perry. She quickly rebuilt him, got him into shape. The couple married in a Hindu ceremony in 1991; the first of their two children had already been born.

“Without Mireille, Lee would have died a long time ago,” Adrian Sherwood says on the phone. Considered to be one of the most important dub producers today, the Brit came to music via punk and old Black Ark records. Sherwood has accompanied Perry since his comeback in the 1980s, and produced his latest album, Rainford. “I wanted to do it like Rick Rubin did with the later years of Johnny Cash and record music that is finally worthy of the legend, where everything comes together – reggae, dub, everything he’s ever done, the whole madness.” Mojo magazine called Rainford Perry’s best album in 40 years. Mireille thinks the record is “terrible.” She puffs on her joint: “Lee sounds so old on it! Right, Lee? You should make dancehall with a young artist! That’s what people want to hear!”

Perry shakes his head almost imperceptibly. “You know what you know. And I know what I know. There’s dirty and clean music, and dancehall is dirty, the dance of the devil. Boredom is the devil, stress is the devil, dancehall is boredom and stress. Clean music is the music of the soul. Every good music has soul.” He rhapsodizes, then reaches for his phone: Well done with hell bitchis donefari season … unbeefsin Akers I’m feeders satan … of late tantan sinernnamicks mo … morning.

Transplanted by his wife to Edelstein, 40 kilometers south of Zurich, Perry was like a flowering hemp plant in a greenhouse. But after all those years away, he still only truly feels at home in Negril, a village on the westernmost tip of Jamaica. He worked there as a bulldozer driver after he dropped out of school, until he suddenly started hearing voices in the earth: “The stones ordered me to go to Kingston Town and to give my music to the world.”

Perry’s house in Negril is right on the shore. It has its own marijuana plantation on the roof – the finest sensimilla. He sleeps during the day and wakes up just before sunset with the crickets, whose shrill song can also be heard on Rainford.

Perry loves insects like he loves every living thing. He strokes the bark of a cedar tree and exalts its texture. Holding a hibiscus blossom in his hand like a wineglass, he mumbles praise for its scent, then takes a picture. He lures a dog over to feast on the rest of his chicken wings, but when the animal doesn’t trust him, he insults it: “Pussy!” Then, he gets back to typing in his smartphone. Criss unwell cry sis fell in America no hearings gratings mareouta hairsputs phrroah China China gangs attacked sinidad jimmy god sinihog Kong queens killer ginger prince … earth rings head. “My head is a computer,” he says of his anarchic wordplay. “The brain of a child. It needs input.” Then, knowledge will flow.

There are few artists with whom you can be so silent. Perry doesn’t even give interviews – he gives “outerviews.” Conversations collapse. Sometimes he speaks in tongues; sometimes he knocks out a rhythm on the table. If it catches on, he starts free-versing, quoting the Bible or pop culture, the sibylline hum of his thoughts carrying him from one thing to the next – his red dyed hair, chicken blood in cocktail glasses, how he would fight the devil “with an army of mosquitoes.” “When I piss, rain comes over the land, and when I shit, thunder rolls!”

Here, he’s untouchable, gliding through the night and past the police checkpoints unmolested. Closed restaurants open up for him. At the Negril Tree House Resort, our club for the night, they put a table on the beach for the awe-striking Perry and his entourage. He’s holding court, a king crowned in glittering bric-a-brac. The public at large keeps their distance, and observes.

There’s a field researcher here – Evan, 30, a graduate student from Detroit and this evening’s minister of higher learning. (He’s working on a film about Jamaican culture and considers himself to be on a “spiritual journey.”) As a gift, he brought Perry a copy of Laozi’s Daodejing. Neville, a friend of Perry’s from back in the day, is currently flipping through it. Neville has gray dreadlocks and a gold tooth, and smiles as he explains why a Rasta never uses the word “believe”: it’s because there’s a “lie” in it. Neville is chief theologist in Perry’s retinue; questions like “do the Jews and Rastas belong to the same tribe?” are addressed to him, and he’s responsible for saying grace at table.

He is also minister of agriculture (weed) and industry (production of joints and spliffs). Perry only smokes pure grass because he is “allergic to cancer.” He gave up tobacco and alcohol years ago. Mireille is the priestess of health, home, appearances, finances. Perry isn’t particularly interested in business – it has the word “sin” in it, which is why he spells it “bizznizz” instead. Mireille has some regrets: her husband has sold rights to his music for less than their value – “Nobody knew that reggae would be so big!” – and doesn’t charge enough for concerts.

Lilliput gets in his head at dinner, and Mireille cuts the food on his plate and makes sure he eats it. Then he gets up to stroll alone in the darkness, down to the water, looking up at the stars. “Leave him,” Neville says. “He’s just going for a piss.”

Later, in the parking lot, Perry suddenly stops. “I see a face in the cotton tree over there. Those are eyes, that’s a nose.” And the whole group stands and stares. “I see the mouth!” Mireille exclaims. “Are those ears?” Evan asks. Neville takes a picture of the tree and shows it to Perry. He studies it for a while with his Haile Selassie face, then finally says, decisively: “We were all wrong. It’s a lion.”

Credits

- Text: Arno Frank