American Menace by Pouria Khojastehpay

032c Gallery is pleased to present “AMERICAN MENACE” by Dutch-Iranian artist Pouria Khojastehpay. On view from February 21 to March 26, 2025 at 032c Gallery Berlin, the exhibition “AMERICAN MENACE” is an investigation of the culture of incarcerated gang members and the American prison system through self-portraits, mug shots, letters, and architecture. It is interested in the relationship between architecture and conflict and how form, function, and aesthetics are deployed to not only optimize systems of crime but also those who intend to fight it.

Unique artworks from the exhibition can be purchased HERE. The books “Mughshawtys” and “Crowbar Hotel” are available for purchase HERE.

Pouria Khojastehpay, Resisting Officer Without Violence (from Mugshawtys series), 2024. Fine art print on laminated aluminium, 55 cm x 55 cm, 1070 EUR.

Khojastehpay has assembled a series of images that were originally in two books he edited, designed, and published with his publishing house 550bc. Founded in 2018, 550bc is part of Khojastehpay’s research practice that is focused on the intersection between conflict, visual art, and the intricacies of (organized) crime. One work series in the exhibition is extracted from his book “Mugshawtys,” which showcases images from Josh Jeffery’s Instagram account of the same name, depicting archived American female mugshots alongside the details of their crimes. The other work series on view includes images that have never been shown before and stems from “Crowbar Hotel: Live from CDCR”—a collection of contraband smartphone photos taken in prison by incarcerated members of the gangs Bloods and Crips. “AMERICAN MENACE” juxtaposes these two image series, almost drawing a binary line between genders and their respective implications.

In conversation with the gallery’s artistic director Claire Koron Elat, the two discuss whether crime can be a luxury product and the complexity of American prison architecture.

(right) Pouria Khojastehpay, Failure to Appear, Speeding, and Driving with Unregistered Tags (from Mugshawtys series), 2024. Fine art print on laminated aluminium, 55 cm x 68 cm, 1070 EUR.

(left) Pouria Khojastehpay, Reckless Endangerment and Reckless Driving - Evading the police on a motorcycle (from Mugshawtys series), 2024. Fine art print on laminated aluminium, 55 cm x 68 cm, 1070 EUR.

Claire Koron Elat: Your publishing house 550bc is interested in the intersection of conflict and visual arts. How exactly do you define this intersection and what made you interested in it?

Pouria Khojastehpay: My interest started at a young age, and one of the main origins was my parents' experiences of the Iranian Revolution and its aftermath. My dad, a war veteran, would show me photos he took during the war with Iraq in the 80s—casual shots, like him in an Adidas t-shirt holding a Kalashnikov. They weren’t glorified, but they had a certain aesthetic that drew me in.

Later, as a teenager, I got into movies about gang culture and prison life in America. This was influenced by one of my cousins—someone I looked up to. He was a bad motherfucker, and his whole look made an impression on me. That added another layer to my curiosity. Those influences were among the first things that sparked my interest in the intersection of conflict, crime, visuals, and storytelling.

CKE: And why did you decide to deal with these topics in printed material?

PK: I never really planned to publish so many books. I was just collecting them for myself. Over time, I started focusing more on gang and war photography. A lot of the books I had were also tied to my Iranian heritage. At some point, I wanted to find a book about crime in Iran, but when I looked, there was nothing. Not even in literature. It was a subject no one really talked about, even though I knew it was out there. I had contacts in Tehran who were part of that world, so I reached out to one of them to see if he’d be open to sharing insights or photos. He was, and he started telling me who was running what, who was gone, who had reformed. He even sent me photos. Some of his uncle, some of his own associates. At first, I only planned to do that one book, but then it grew from there.

CKE: How do you come to the subjects for the books you have published that deal with different specialized themes?

PK: It depends on who reaches out—whether it’s the subject themselves or a fixer, someone who connects me to the right people. From there, I look into what’s already out there on the topic and see if it interests me. It has to resonate. I never force anything. It all happens naturally, and that’s how trust is built. I’m not an investigative journalist. Everything is approached in a friendly, relaxed way.

(left) Pouria Khojastehpay, Crowbar Hotel 5 (from Crowbar Hotel series), 2024. Fine art print on laminated aluminium 56 cm x 55 cm, 1070 EUR.

(right) Pouria Khojastehpay, Crowbar Hotel 10 (from Crowbar Hotel series), 2024. Fine art print on laminated aluminium 55 cm x 55 cm, 1070 EUR.

CKE: You mentioned that one of the reasons you founded the publishing house was because you felt like there was something missing around certain topics. Do you still feel that way?

PK: There have always been publishers covering these topics, but I got tired of traditional photography. I lost interest in seeing everything through a photographer’s lens, filtered by them and their editors. That’s when I became more drawn to archival work and self-made content from the subjects themselves.

One of the books that pushed me in this direction was by a German photographer, Arwed Messmer. He made a book called Reenactment, MfS, where he went through old East German archives and created a seamless narrative—without taking a single photo himself. He used existing archival material to tell a new story, and that approach really stuck with me.

Another big influence was Teen Angels magazine. It was built entirely on self-made content—Chicano gang members and inmates sent in their own photos, letters, and drawings, and the editor just compiled them into something raw and authentic. There was no outside filter, no photographer shaping the narrative, just the culture speaking for itself.

With social media, this kind of content became more accessible. There wasn’t a publishing house focused on this niche, and there weren’t many books made in this archival manner of fashion. So I decided to fill that gap. But I still work with some photographers and find traditional documentary photography important and necessary.

CKE: Do you usually travel to the places you make books about?

PK: It depends. Sometimes it’s close. You meet someone. But for example, I haven’t been to Brazil or Mexico yet.

CKE: Do you prefer working with a middleman or being in direct contact with the subjects?

PK: I always prefer to have direct contact, but sometimes that’s not possible. Some subjects want to stay anonymous, which is safer for everyone. It really depends on the seriousness of the situation—how much heat is on them, whether they’re on the run, or if there’s any risk for me or the fixer. In those cases, the form of contact depends on what makes the most sense. Other times, it’s more casual, and I end up meeting someone through certain social circles.

CKE: You grew up with a war veteran father and then came to the Netherlands as a refugee as a young child. How do you think that has impacted your work and your upbringing?

PK: I was a baby when we fled, maybe one year old, but we spent six or seven years in a refugee center. At first, we moved around a bit, then we stayed in one place. This was from the early 90s to the 2000s, during a time when multiple conflicts were happening at once. The Somali Civil War, the Yugoslav Wars, the Gulf War, the rise of the Taliban in Afghanistan. Refugees from all over were coming to Western Europe, and at the camp where we lived, people from all these different backgrounds ended up together. So, I grew up around kids and families from war-torn countries. As a kid, that was just normal. It was the environment I knew. As I got older, I started to understand their backgrounds more and why they were the way they were.

“Mugshawtys” book cover, Crowbar hotel book

CKE: It’s clear how much war and other conflicts impact the lives of families and individuals, oftentimes until the end of their lives. The topics you deal with also often go hand in hand with social precarities and racial discrimination that then kind of “automatically” lead to crime. As you said, if you grow up in a certain environment, this is the state of normalcy for you. So, if you grow up with crime, violence, and drugs, this might be the normal state for the rest of your life. And since we’re also showing some gang members in the gallery show, there are certainly many cases where that was the situation. It’s quite tricky, since it doesn’t excuse any committed crimes of course, but perhaps explains their background.

PK: I don’t think anything justifies crime, but when you grow up in a certain environment, it becomes generational. Especially with the portraits in Crowbar Hotel—a lot of them don’t know any different. They have certain role models, limited choices, and face systemic racism in court. Once inside, prison politics take over. Short sentences turn into longer ones because survival often means joining a gang or doing something for protection.

People commit crimes for different reasons—survival, desperation, the thrill, fast money, or a sense of belonging. Some are calculating and predatory, taking advantage of whoever they can. Circumstances, trauma, systemic failures, and personal choices all shape who someone becomes.

To give an example, when you keep getting rejected for jobs based on stigma alone, at some point, you say, “Fuck you,” and find another way to make money. In Europe, some ethnic youth facing that reality turned to organized crime. During the Syrian Civil War, others left to fight for ISIS or against them with rebel forces. That kind of decision-making process and those moral dilemmas are what intrigue me.

CKE: Do you think it’s the government’s task to work more on prevention?

PK: I don’t know if you can blame just one system or institution. It’s more complicated than that, and a lot of it comes down to individual circumstances. As for prevention, I don’t have a clear answer. In theory, the government or society should take more responsibility, but in reality, things are rarely that simple.

CKE: In the show and in the book Crowbar Hotel, there are a number of different drone images showing different prison complexes in the US. You see how there are architecturally and visually striking parallels between the layout of prisons, war bunkers, and military installations. When you investigate these relationships between architecture/aesthetics and crime and conflicts, what exactly have your findings been?

PK: Yeah, when you look at American prisons from above, especially most of the CDCR facilities, the similarities to military installations are hard to miss. A lot of them are built like a bunch of war bunkers. Isolated, heavily fortified, and designed for control rather than rehabilitation. Many are stuck in deserts or far-off rural areas, making them hard to reach. That distance makes it easier to forget the people inside. It also makes it harder for families to visit, which adds to the isolation.

The farther these prisons are built from everything else, the easier it is for people to ignore what happens inside. Out of sight, out of mind.

Pouria Khojastehpay, Crowbar Hotel 6 (from Crowbar Hotel series), 2024. Fine art print on laminated aluminium 55 cm x 55 cm, 1070 EUR.

CKE: There is a statistic that while the United States has around five percent of the world’s population, it has 20 percent of the world’s incarcerated people. In comparison, China has like four times more inhabitants but much fewer incarcerated people.

PK: I think it comes down to a mix of things. Strict sentencing laws, mandatory minimums, the war on drugs, and racial bias all play a role. Every state has its own system, so in some places, it’s way easier to end up behind bars than in others. People serve long sentences even for minor offenses, and once you’re inside, it’s hard to break out of the cycle, especially with how prison politics work.

CKE: That’s crazy. At the same time, your books are visually appealing and play with design language.

PK: I mean, the books are open to interpretation, but there’s always context. Each one includes background information, whether it’s about gang members in prison or drug cartels in Mexico. There’s always a narrative, sometimes even academic research. At the same time, they’re visually appealing, which is why some people buy them just for that.

In the end, they’re coffee table books. They’re meant to be displayed, and they’ve become hyped and in demand. But they’re still rooted in anthropology and sociology. A professor even called it visual criminology. People who think I glorify anything usually haven’t read them. If you just see the content on Instagram, I get why it might come across that way.

CKE: Would you say that you’re also explicitly playing with this juxtaposition of gore and “glamorous,” or “Instagrammable,” images since it draws a bigger audience?

PK: Yes, I have to. In the end, it’s a product, and coffee table books a luxury product.

Take Scarface, for example. It’s really a story about greed, paranoia, and self-destruction, but because it looks stylish, people admire it. They watch it, see the lifestyle, and want to be Tony Montana, even though the film is actually a warning. Same thing here. You have to make it visually appealing to pull people in. They’ll see the cool pictures first, but hopefully, they’ll read the text and start thinking about the consequences of that world. Which is often prison or a casket.

CKE: The world we live in is also a lot about the intricacies of right and wrong. Would you judge between right and wrong? And, when you talk to some of these subjects, do they distinguish between right and wrong?

PK: The world isn’t just black and white, but of course, I judge between right and wrong, like anyone else. Some things are just cruel, and there’s no excuse for them. But when you talk to people who’ve committed crimes, it’s never that simple. Some fully know what they did was wrong. Others justify it, twist the logic, or see themselves as victims of the system. And some don’t care at all.

When I talk to some of my sources, it’s clear not everyone sees right and wrong the same way. Some regret it, some think it was necessary, and some never even questioned it. It depends on the person, their background, and how they see the world. I try to understand where they’re coming from, but that doesn’t mean I agree.

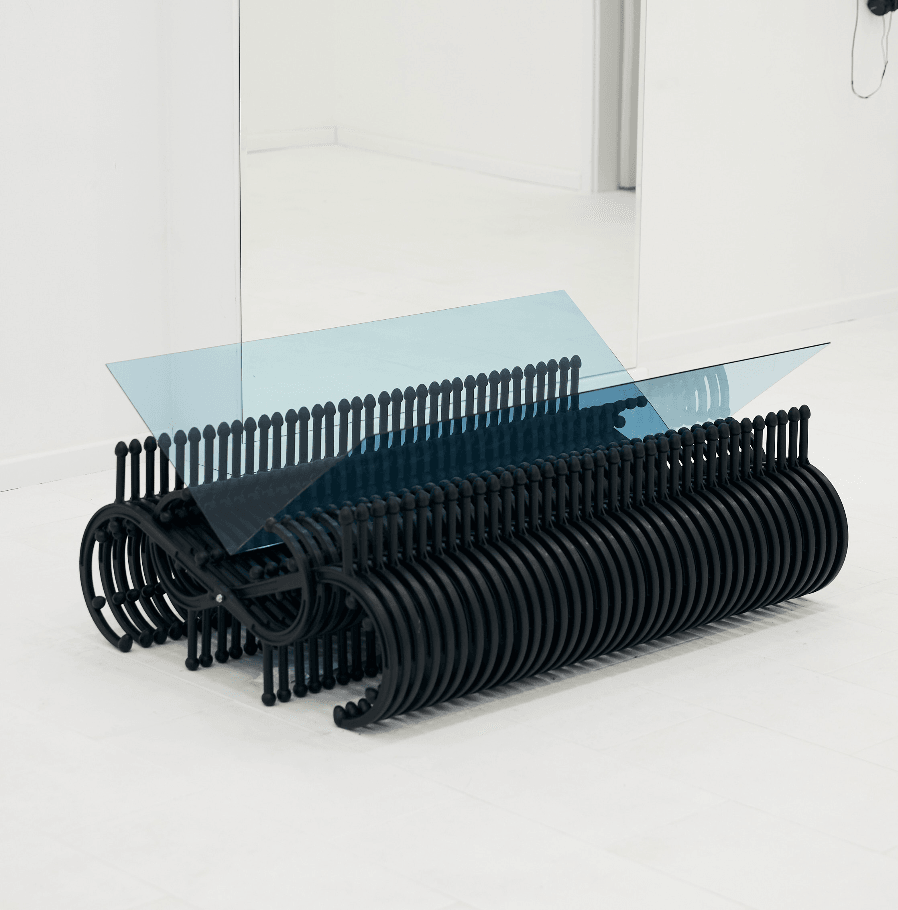

Documentation of “American Menace” by Pouria Khojastehpay at 032c Gallery

A portion of the proceeds will be donated to Homeboy Industries.

SOCIALS

Credits

- Installation View Photography: Robert Hamacher