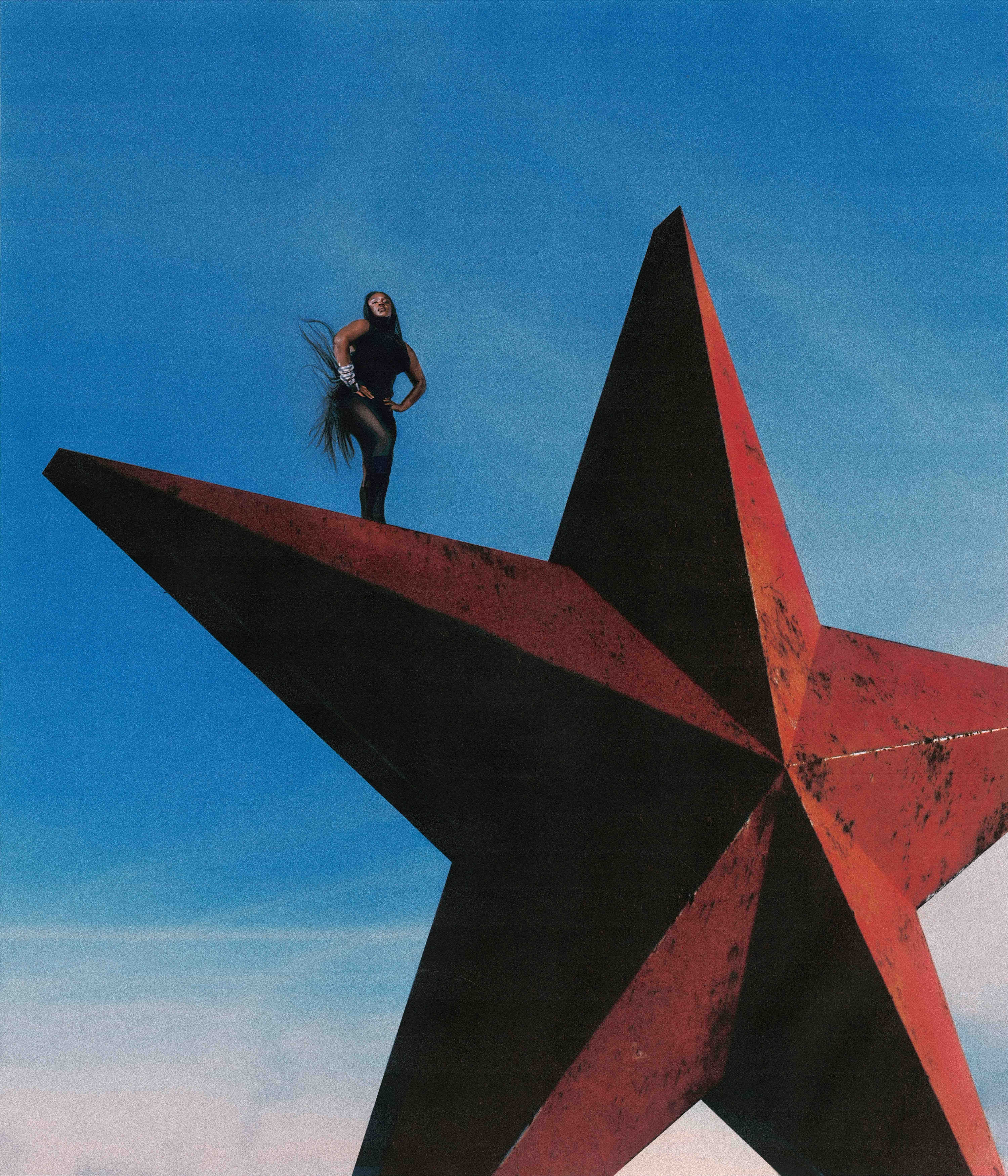

Amaarae: Black Star

|Phillip Pyle

Two songs into Amaarae’s BLACK STAR (2025), the Ghanaian-American artist and producer’s scintillating new dance music album, rapper Bree Runway introduces us to “CzechSlovakAtlanta,” a place of unbridled frequencies, possibilities, and encounters that perhaps only Amaarae’s music could take us. On the precipice of that pulsing zone, Runway asks, “Do you like disco, rave?танцевальный клуб?”. Then, Amaarae breaks it all down into a rapid-fire club track where ketamine, coke, and molly are aplenty and the only imperative, whether you’re in Central Europe or the American South, is to “serve somebody.”

BLACK STAR is an album marked by its movement. Alchemized from Amaarae’s desire to recreate the sounds that first entranced her during childhood and her time spent immersing herself in the nightlife scenes and music histories of Miami, Los Angeles, São Paulo, Detroit, Chicago, and her hometown of Accra, the albumtraverses the spectrum of Black dance music with a futurist bent. Lasers shoot, guns pop, and whistles blow as the album cycles through Afrobeats, Jersey club, Detroit ghettotech, Chicago house, Brazilian baile funk, and Ghanaian microgenres, including azonto and kpanlogo. Along the way, an ever-changing cocktail of bumps, pills, doses, and dark liquors distend and suspend time, making space for hours on a sweat-laden dance floor, backroom rendezvous, and even a second to merely people watch from the fringes. By the album’s end, one is left with a dizzying number of takeaways. The chief of which is that Amaarae asserts herself as a star whose prowess is neither limited to genre nor geography.

One week after the release of BLACK STAR, Phillip Pyle spoke with Amaarae about the childhood memories behind some of the album’s most notable moments, her ideas for the future of Ghanaian music, and embracing her vocals as a curatorial choice.

jacket VIVIENNE WESTWOOD earrings MUGLER

Phillip Pyle: This album was born in transit. Were there any moments, be they childhood memories in Accra, New Jersey, or Atlanta, that particularly shaped this album?

Amaarae: There are so many moments that shaped the sonic direction of this album. When I was probably four or five, “Believe” (1998) by Cher came out. I lived in Ghana at the time, and I loved that song because Cher bore an uncanny resemblance to my aunt. I would look at the video and be so confused, thinking, “Does my aunt have a sister? Or is that my aunt on TV?” It’s a beautiful song, but I’ve loved it all my life because of this one minor detail.

"Starkilla" goes back to my time in Mount Olive, New Jersey, when I was 13 years old and on Myspace. I went to this girl’s page and she had "Discoteka" by Starkillers on it. I thought, “Holy shit, what is this?” That was the beginning of my introduction to trance music and getting into Deadmau5 and Kaskade.

For me, everything starts from songs that I loved as a kid. I grew up wanting to recreate those feelings. Then, during this project, I was having a lot of fun in places like Miami and Brazil, and I didn’t want to make a project that felt as heavy as Fountain Baby (2023). There was so much going on in Fountain Baby. It’s very maximalist. This album is a bit more minimalist. It’s also a bit more daring—more fun, more punk, more exciting.

PP: Are there other ways that this era differs from the Fountain Baby one?

A: Everything is more community based—even the visuals. I went back home to Ghana and invited all of the alt kids, all of the taste makers I’ve known for the last ten years. I was like, “Hey, we’re shooting this video for ‘B2B,’ pull up and let’s turn this into a party for us.” That is what the album is about. Fountain Baby was very internal. This time around, I decided to tap into the fans and the community that made me.

PP: Were you still tapped into the scene in Accra or did you need to reorient yourself?

A: No, absolutely not. I go back every year. I chair the only ballroom event that we have there every year. I’ve been a part of the scene for a good ten to 15 years. Those are my people for real, not for fake.

PP: You’ve moved between Ghana and the US throughout your life. You also lived in London for two years. Has your relationship with Ghanaian identity changed over the years?

A: I’ve come to appreciate it way more. I’m proud of where I’m from. I’m proud to represent it, but I’m also proud to be an outlier who not only represents the country but represents the outliers of the country. I think that traveling through the world made me appreciate where I come from. It’s made me appreciate my nationality and what that nationality has given me from a cultural and educational standpoint.

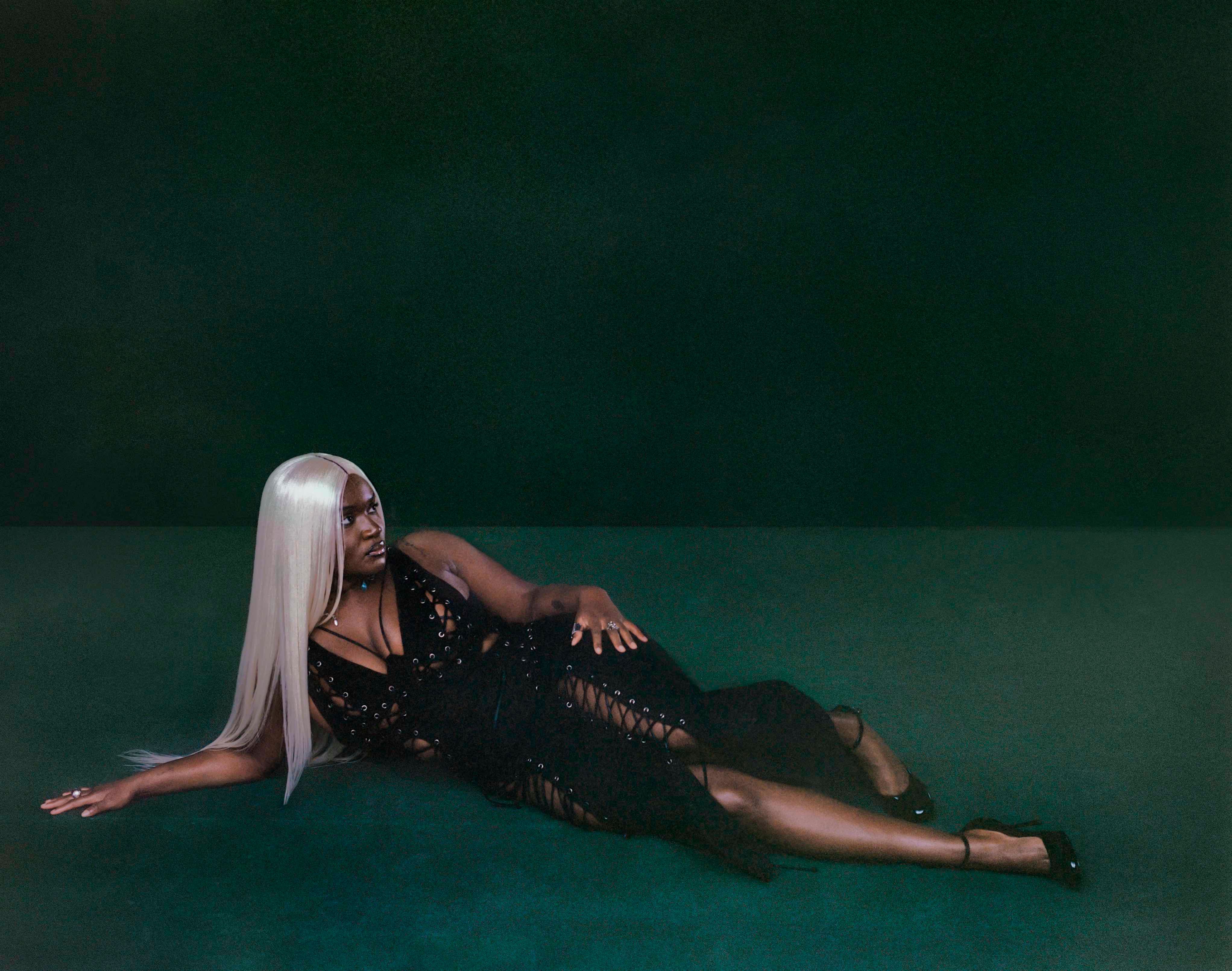

bodysuit ATSUKUO LATEX shoes CHRISTIAN LOUBOUTIN

PP: You recently posted a video on Instagram with Bree Runway, who is of Ghanaian descent, where you debunked false claims that there are no Ghanaian artists on BLACK STAR. When you put so much time into crafting a sound and a concept, are there particular criticisms, whether true or not, that are harder to deal with than others?

A: A lot of Ghanaians had an issue with the “no Ghanaian” thing but it was just because they didn’t see Ghanaians represented in the way that they typically do locally. For me, this was an introduction of Bree Runway to a more localized Ghanaian audience.

Outside of that, I also got a lot of criticism for the production. A lot of people were like, “this doesn’t reference Ghanaian music and culture in any way.” I debunked that as well. I have a vision for what the future of Ghanaian music sounds like, and this is my interpretation of it. I’ve taken from local sounds such as azonto, kpanlogo, hiplife, and highlife, and this is the future that I see our music going in. Otherwise, it’s going to stay stagnant.

For people to say there’s no Ghanaian influence is crazy because there’s always been Ghanaian influence in my music. But I’m such a fusionist that, instead of using typical instruments that you hear in a rhythm, I’m going to use a kick for the same rhythm change that would typically be a clap or a snap.

I also think a lot of fans who loved Fountain Baby hated this album. And I’m like, “What were you expecting?” Fountain Baby sounds completely different from my first album, THE ANGEL YOU DON’T KNOW (2020). In order for me to keep going and keep people on their toes, I have to evolve. I’ve learned to not care about criticism because I know the time, effort, and the research that I put into things. I’ve put in the 10,000 hours. And I know that if I make a product, I can stand by it. All that matters is that it’s not a lazy, under-researched, under-executed effort. The story is: I don’t give a fuck.

PP: I’m assuming that people didn’t like the pivot to dance music even though you are still interpolating a lot of pop elements throughout this album.

A: I saw a lot of people who hated the Cher interpolation. I thought that shit was fire. I don’t know who on Earth is going to think of “do you believe in love after drugs?” Even with “Starkilla,” which has the Kelis reference, a lot of people were like, “What is ‘When this beat go blama in CzechSlovakAtlanta’?” To me, that feels like comedy. But, also, if you’ve ever heard “Discoteka,” it has a very weird cadence and feeling. The lyrics are cerebral and strange. I wanted to bring some shit like that to “Starkilla” but in a more ghettotech, Black, urban way.

PP: It’s interesting to hear that people were disappointed or didn’t like the ties you were making to locality. Even with “Starkilla,” I saw the Euro techno beat paired with “CzechSlovakAtlanta” as a way of gesturing toward the diaspora of dance music at the same time that you’re referencing its Euro popularity.

A: Thank you! I think because Fountain Baby was so layered, people thought, “she’s so heady and so intellectual.” But when I do something simple, the same intellectualism or thought process isn’t applied. Even the simplicity, in and of itself, is an intentional choice. When you say something like, “CzechSlovakAtlanta,” it means whether you’re in Czechoslovakia or Atlanta, bitch, this is supposed to be for everybody.

dress DILARA FINDIKOGLU bangles DINOSAUR DESIGNS shoes CHRISTIAN LOUBOUTIN

PP: That feels like the thesis of the project.

A: Type shit! That’s what I think, but you know… [Laughs]

PP: You’ve said that you typically sway in the corner at a club, which is also what you’re doing in the video for “Fineshyt.” Have you picked up on dance music knowledge and dynamics through just observing from the peripheries over the years?

A: I’m not observing as someone that’s in the field doing research. I go to the club to have fun and dance. When I’m sitting and looking, I’m just people watching. But, from a musical standpoint, I’ve been listening for years and years to Claude Young, DVS1, Kaskade, Deadmau5, Modjo, MJ Cole, and Sia when she was doing garage. The list goes on and on. I was just a kid who loved music, and I think that I can tap into and put my own spin on anything I want to because I’ve spent so much time listening to and actively being a part of music.

My pivot to dance music came from two things. One was thinking about what to do after Fountain Baby that would excite me, in a genre that I haven’t forayed into. I even think about my GOAT Beyoncé dropping Renaissance (2022), which built cultural cachet and changed the understanding of the average fan, such that Charli XCX could come and have an ascent.

Second, from a political standpoint, the world is a crazy place. Artists are creating music that fosters community so that we can come together and exchange ideas, love, and passion. Eventually, that starts to unify a collective against the political structures that are trying to oppress us. So, when I approach my music from this standpoint, it’s because I want to build collective community and consciousness. It’s also indicative of where I’m at in my life. I want to have fun. And when Beyoncé did it, I was inspired. I thought, “That’s a lane that I can put my own spin and African interpretation on.” And that’s what I did.

jacket VIVIENNE WESTWOOD shorts VIVIENNE WESTWOOD shoes DUHA earrings MUGLER

PP: A project that surveys dance music is inevitably going to be about queerness, too, which is something you explore on BLACK STAR as well as on past projects. Throughout the process of making the album, did it take on a heightened political dimension due to recent rollbacks—in the US, for instance—in LGBTQ+ rights and other conservative trends in global politics?

A: I didn’t come at it from a political standpoint. If I did, a lot of the language would have been different. I came at it from the idea of bringing people together. I think that when people come together, conversations inevitably start or ideas are shared. When I was thinking about the climate that we’re living in, I didn’t want to bring something dark into the world. I wanted to bring something energetic, fun, and funny. This is my contribution. As an artist, my goal is to bring joy to people. What they do with that joy is their responsibility moving forward.

If you really think about some of the ideas or themes that are consistent throughout the album, I’m standing firmly in my beliefs in a very clear and open way. That in and of itself is a mission statement. It’s a statement not just about love and acceptance but also about being brave and clear in what you want and how you want it. I think that’s also visible through the visuals, which all include my community. You don’t see me unless you see like 50 bad bitches—unless you see me in a setting where people are dancing, in a space that’s quirky, like the “S.M.O.” video where I’m buffing an ass cheek. I’m trying to bring some sort of reverence to this world, but in the context of community.

PP: How did the features expand this sense of community?

A: The first voice you hear is me, the second voice is Bree Runway, the third voice is PinkPantheress, and the fourth voice is Naomi Campbell. I don’t know how much more “Black star” it can get. You have the Black stars from Ghana, the avant-pop auteurs from London, the most iconic Black supermodel of all time, and the OG of The Gap Band, Charlie Wilson, who has made everybody dance from 1950 to now. I think that that speaks on its own. I’m representing all of these different lives and all of these different stories that have brought us confidence, joy, and, as Black people specifically, a boldness that we’ve been able to explore art and music with. To me, these people are some of the best representations of that.

PP: Were all of the features people you originally had in mind? I’m curious how Naomi Campbell got involved.

A: The initial idea was for Naomi to do “Starkilla,” but it didn’t feel aligned. “ms60” is a song about getting the angles on some fashion shit, and I thought, from a curator standpoint, how fucking dope would it be to get Naomi Campbell to do ad libs while I’m rapping? I saw a lot of people say, “Oh, that Naomi Campbell feature wasn’t utilized properly.” I think it’s fly that she’s doing ad lib while I’m rapping. None of you bitches have a Naomi Campbell feature. She came to the studio on her bodyguard’s back because she has sciatica, and was like, “Alright, I’m about to knock these ad libs out for you.” Like, please! To me, that feels iconic.

With PinkPantheress, I literally woke up and thought, “What if I put PinkPantheress on “Thong Song” but on some hyper-pop shit mixed with tech house?” I explained the idea to her, and Vicky [PinkPantheress] sent me a whole song back. I was like, “Alright, if we approach it that way, it would sound more like a PinkPantheress song, so I need to take some parts out and approach it from the Amaarae perspective.” She was really graceful, and we went back and forth on that song together.

With Charlie Wilson, I just had to get a song with the OG—just because of how involved he’s been in my life. The Gap Band has soundtracked so many iconic Black moments, from Black barbecues to Black weddings to Black parties to Black concerts. Charlie was also involved in another generation with Snoop Dogg, Pharrell, Justin Timberlake, and Kanye West. He’s been such a part of the fabric of Black music that has been forward-thinking, genre-bending, and world-changing to me. When he agreed to do it, it felt like the ultimate co-sign.

PP: In the past, you’ve called yourself a “producer first, writer second, vocalist last.” With BLACK STAR, would you add curator to that list?

A: One-thousand percent. I’ve executive produced all my albums. I’ve always picked my features, I’ve always done the tracklist. I’ve always thought about the production from the inception of the concept. I don’t receive beats from other people, then think, “All right, now let me write.”

I’ve always been a curator—you know what I mean? I feel like I’m a curator first, executive producer slash producer second, writer third, vocalist last. Vocals are just a means of being on my own tracks.

PP: And it’s your means of communicating your concept.

A: Exactly. I could be a producer but I don’t know who could say the things that I want to say as well as I can say them. So, I have to find my way around how to use my voice—because I’m not the best singer in the world, and I’m totally OK with that.

dress DIPETSA shoes DREAMING ELI necklace DOSISG6C

Credits

- Text: Phillip Pyle

- Photographer: Michelle Helena Janssen

- Styling: Elshhyy

- Makeup: Sk1nnyy

- Hair: Ivy May

- Production: Marvellous Last Night

- Executive Producer: Max Alan

- Art Director: Kenechi Carmel

- Movement Director: Ayanna Birch

- 3D Artist: Ben Dosage

- Models: Nalu.lu, Tadi Bravo, Biba Williams & Syren Gray

- Lighting Tech: Cassian Gray

- Production Coordinator: Isaac

- Styling Assistant: Dianah Gwendu

- Lighting Assistant: Ian Man

- Art Assistants: Francesca, Noairakira & Ikemdi