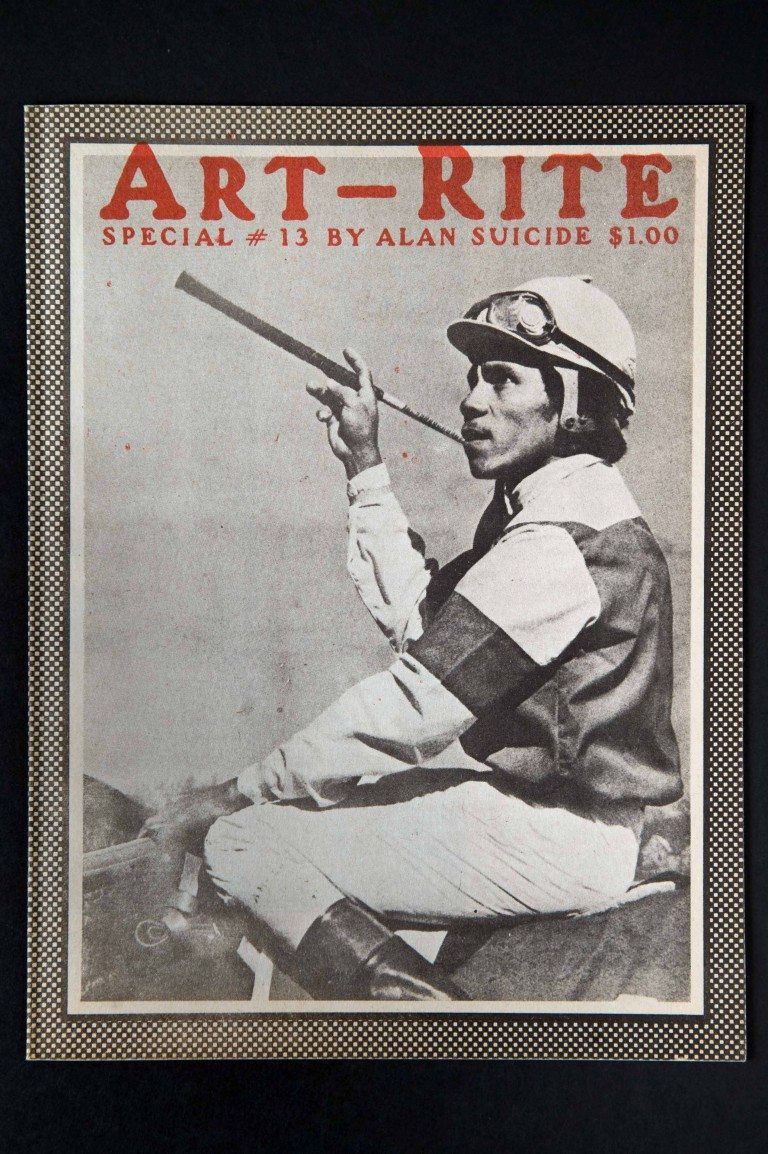

ALAN VEGA’S Legendary Art-Rite Issue #13

Un-made in the USA: presenting the complete issue of the downtown art journal guest-edited by the late artist and SUICIDE musician.

This Sunday, a hero of 032c passed to the other side: the New York musician and artist, Alan Vega. Born in Brooklyn in 1938, and one half of proto-punk, proto electronic music duo Suicide, his work spread from live performances to sculpture to curation. Now standard, in the early 1970s, the merging of gallery and rock band were a marriage of connivence for extremists: in the words of curator Mathieu Copeland, Suicide was only “able (or allowed?) to play in art galleries.”

Working, living, playing and making at the center of the New York downtown, his path regularly crossed with another lodestar of 032c: Art-Rite, the boldly by-artists, for-artists DIY journal founded by Edit deAk, Mike Robinson and Joshua Cohn in 1973.

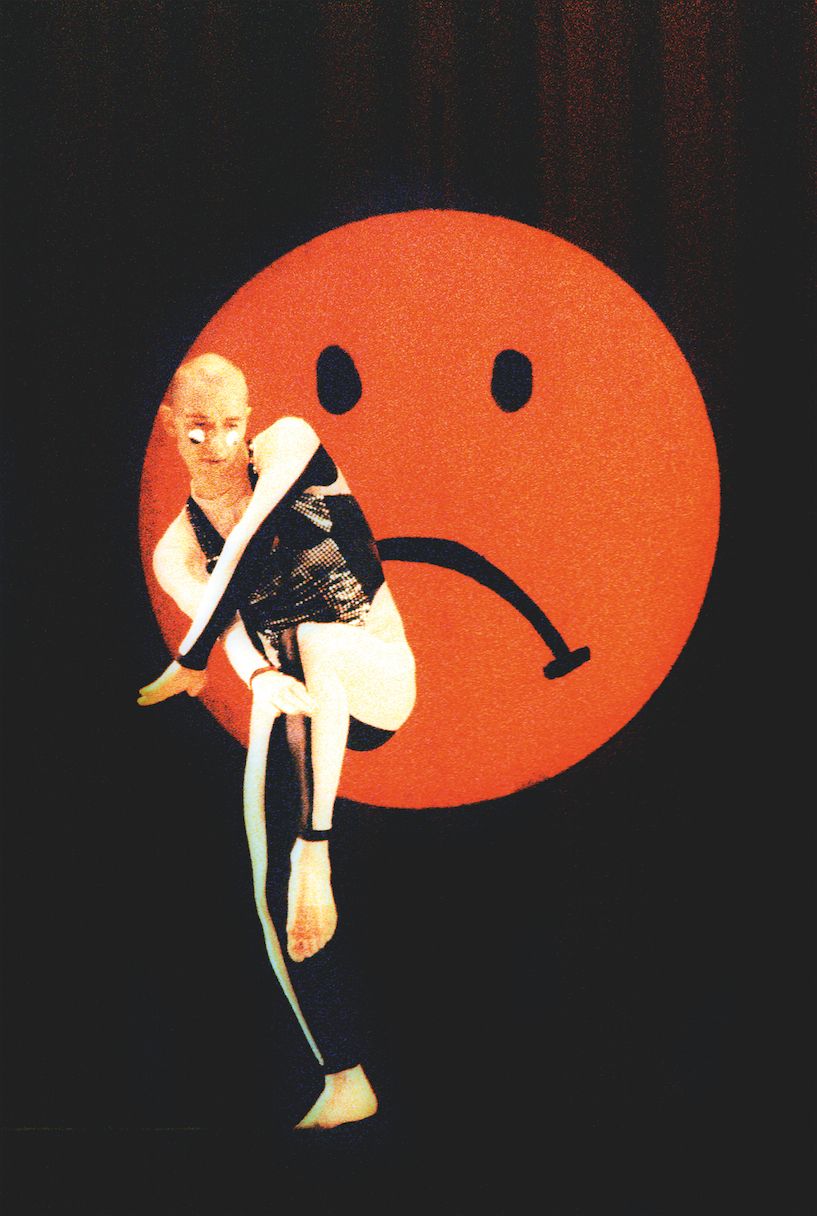

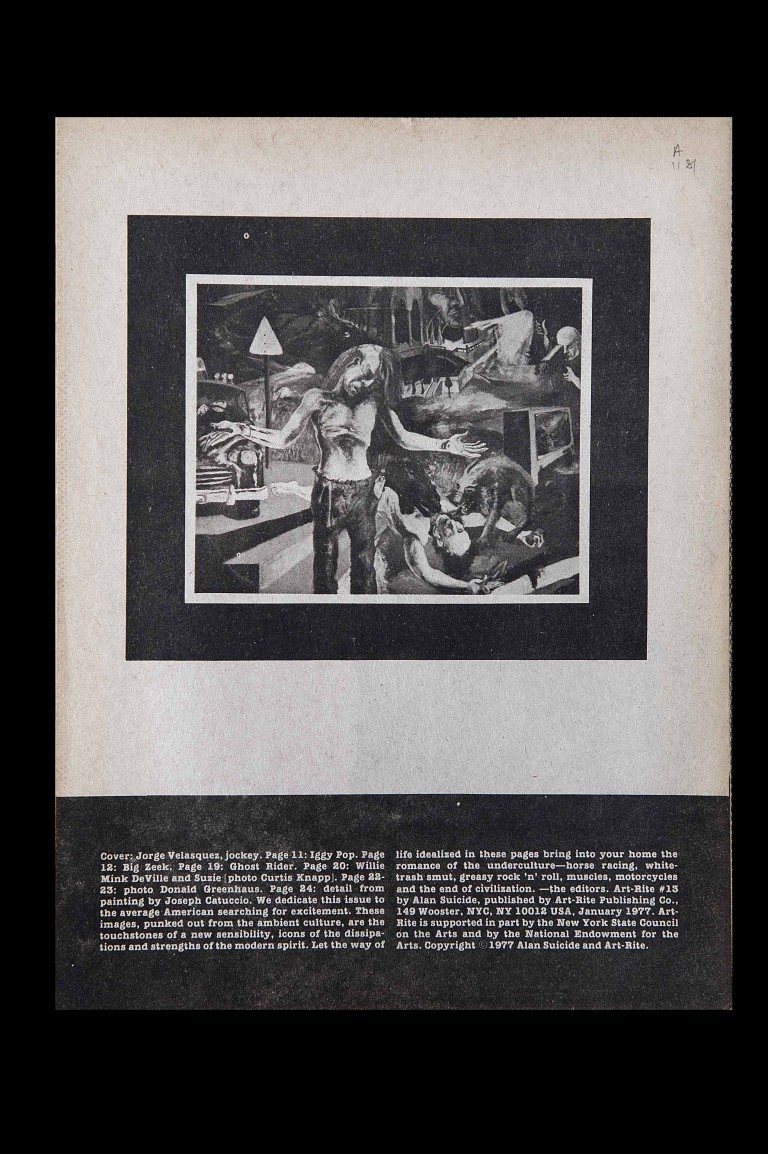

Having previously covered Vega’s work under the headline “Alan Suicide: Prophet of the Little Guys’ Apocalypse,” in 1977 Art-Rite turned over the editorship of Issue #13 to Vega, who curated across its 24 pages a set of found images. It was an H-Bomb in the desert: a moment for independent art magazine editors comparable with the Sex Pistols show at the Manchester Free Trade Hall few months earlier.

We are pleased to present the full magazine, online for the first time (to the best of our knowledge), with an interview with Copeland, who in 2009 curated Infinite Mercy, Vega’s retrospective at Musée d’Art Contemporain in Lyon.

You were born the year of the issue’s release. How did you come to be so close to Vega and his work?

MATHIEU COPELAND: 1977 was a breakthrough year for Alan Suicide. Yet, we must remember that Alan, then Alan Bermowitz, in the late ‘50s, studied with Ad Reinhardt and Kurt Seligmann at Brooklyn College, focusing initially on painting and drawing. Over the next two decades Alan would gradually build an impressive body of work, and a radical philosophy on art and life. In 1969, Alan Suicide was a founding member of MUSEUM: A Project of Living Artists, one of the first alternative artist-run spaces in New York, and throughout the late 60s and 70s had exhibitions in places as varied as MUSEUM, OK Harris, Gallery Marc in Washington or the gallery of the University of Florida. Then in 1977 the solo issue of Art-Rite came out, the first Suicide album was released, and Alan Suicide became Alan Vega.

In 2006, I curated “Soundtrack for an Exhibition” at the Musée d’Art Contemporain in Lyon, France. I invited Susan Stenger to compose a soundtrack, a continuous piece that would last for 96 days. For this, Susan invited a stellar list of musicians to contribute to the making of this epic piece, including Alan Vega. From then on I have had the joy and privilege in working closely with Alan, especially in curating his first retrospective at the Musée d’Art Contemporain in Lyon in 2009, and editing the first comprehensive monograph on his work, bridging his entire body of work – from the light sculptures through to his drawings and paintings.

Julian Schnabel said “Alan Suicide alias Alan Vega has been meditating on the crucifixion, death and ecstasy with every sensory pore in his body.” How does this come through in the pages of issue of Art-Rite?

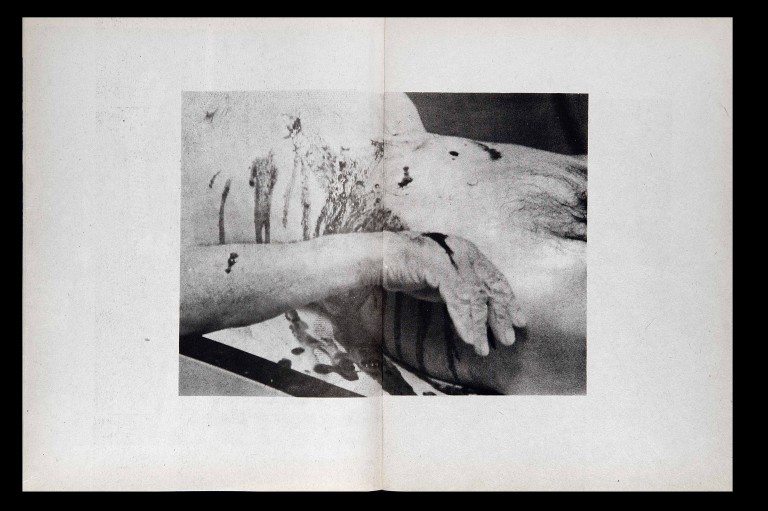

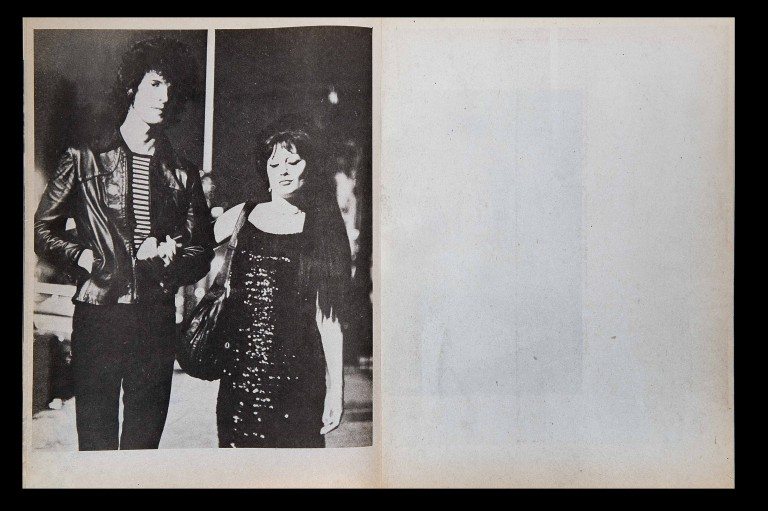

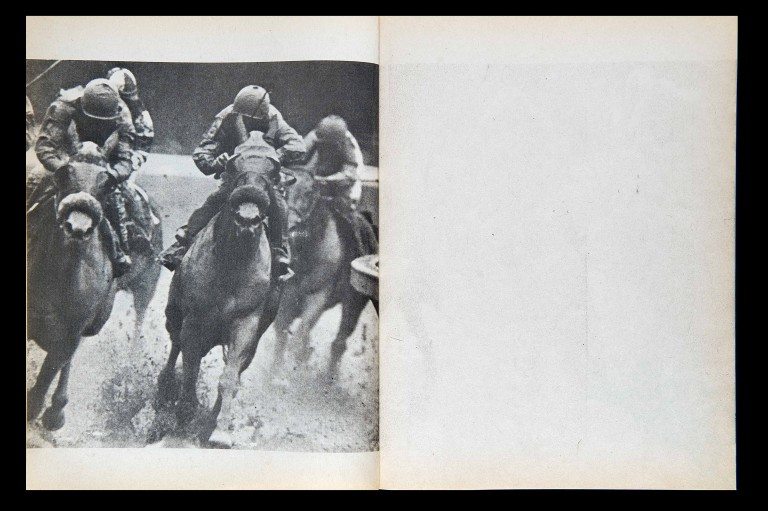

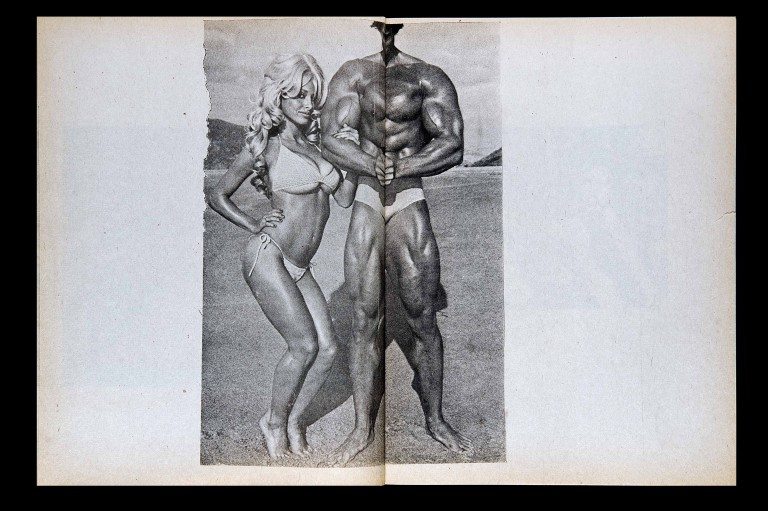

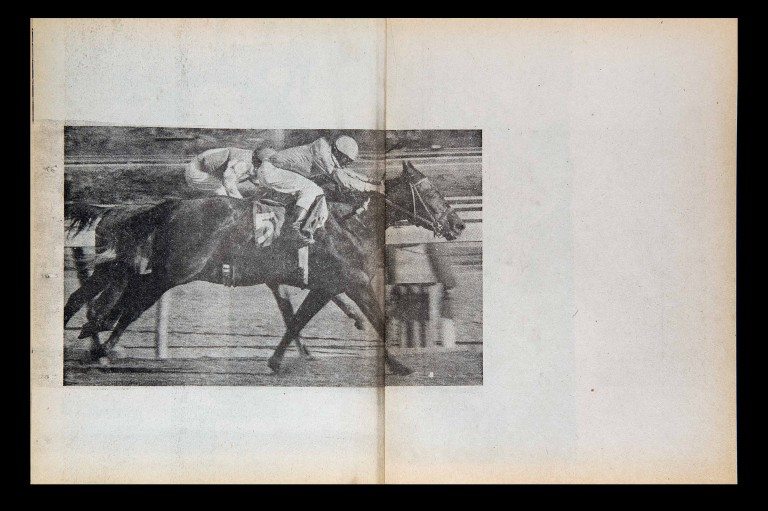

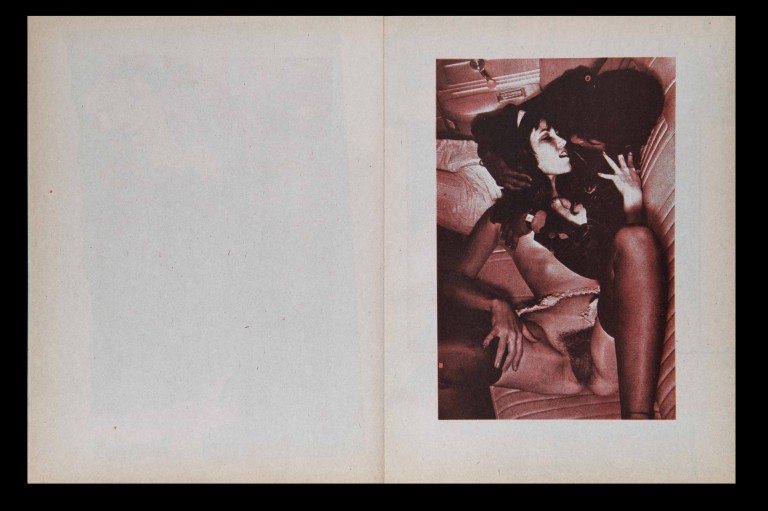

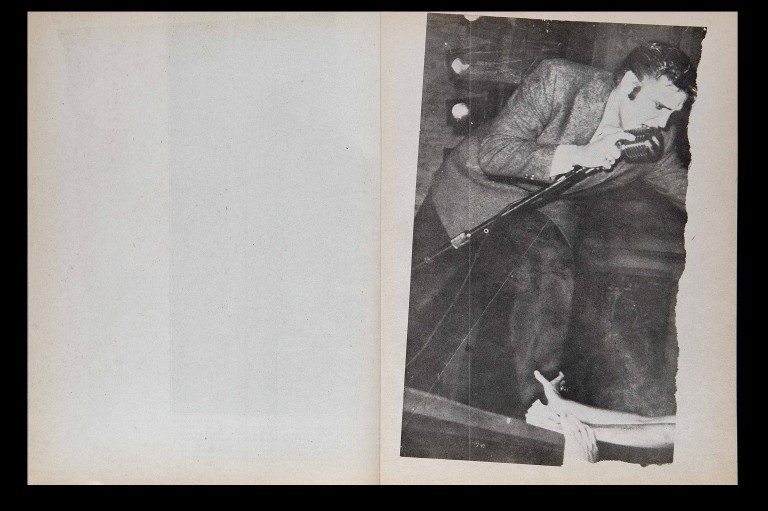

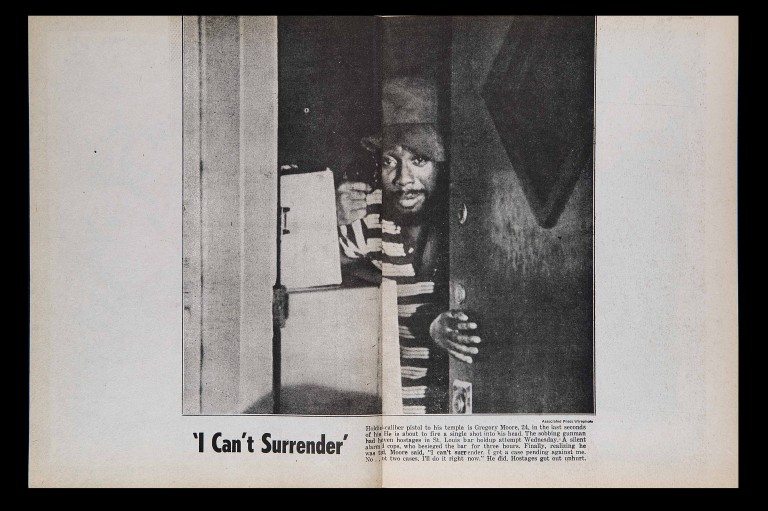

This issue of Art-Rite encapsulate all that created Alan’s personal cosmology, from horse racing (Alan’s passion) through to Elvis and Iggy and a critical vision of the Americana. Yet it is also striking to find in these pages a celebration of life, of popular culture (the Ghost Rider), sex, and crucifixion, as we can see in the details chosen by Alan of the painting by Joseph Catuccio. Mortality plays an important part of the making of this piece, as we can see in the double-spread of a picture taken inside a morgue by Donald Greenhaus.

A striking characteristic of Alan Vega’s art is its use of recycling. Alan Vega went to the streets to gather the raw materials for his works and presented them in the gallery. After the exhibition, he returned them to their primary reality by throwing them back to their origins. Somehow the same can be said about Suicide’s music – it encapsulates the energy, recycling the city’s electricity.

When I came to prepare the monograph for the retrospective, my desire was to reproduce in its entirety the solo issue of Art-Rite that had become a rare and collectible item. To further this desire, as an echo to this striking piece from 1977, I invited Alan to realise Let U$ Pray, a new 16-page booklet that concluded this publication, revealing yet again an up-front and uncompromising reading of our contemporary world.

“His art is a deep understanding that nothing lasts forever.”

At the time of Suicide, central New York was in ruins. It’s not any more. Can you separate Vega’s art from his place, and his time?

His using of the classical motifs, for instance that of the cross, insists that his art was for the historical then, as much as the present now. His art is a deep understanding that nothing lasts forever. Anti-aesthetic, anti-formalist, the equivalent of an “un-made in the USA” Arte Povera, Alan Vega’s work embraces the contemporary reality in which we are all immersed.