A Photograph Is a Photograph: LIZ JOHNSON ARTUR

|Katja Horvat

There is a continuous narrative to Liz Johnson Artur’s body of work, which is dedicated to capturing and preserving memories while building an ever-evolving archive. Her Black Balloon Archive, which she started in 1991, is driven by her desire to create tangible memories and connect with people using photography to investigate and engage with others.

Black Balloon Archive is a visual representation of the way the artist experiences life, capturing mundane encounters. Johnson Artur’s work is instinctual and her archive is “a matter of accumulating photographs and trying to make sense of them.” With a practice rooted in personal identity, she explores ideas through lived experiences.

Her all-inclusive approach explores commonalities and differences within the cultural contexts in which they occur. In the moments she captures, she is fully present, and as she often remarks, it's all about “tasting it, relating, and experiencing the moments together,” even if sometimes just for a few brief seconds. Artur Johnson’s ethos is one of shared humanity.

KATJA HORVAT: I want to start this off with Dusha. In Russian and Slovenian, which is my native language, the word means soul. “Dusha” was the name of your first museum exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum back in 2019 but in retrospect, the word basically sums up your oeuvre, and what you are after in the photographs you take.

LIZ JOHNSON ARTUR: There you have it. Being from Slovenia, or any other ex-Yugo country, you understand it right away. I try to gain people’s trust and make them feel comfortable, so I can really capture one’s soul and essence. And when I do it, I try to do it in the simplest and most sincere way. I don’t like analyzing things and dwelling on a moment, I want to be in it. I want to taste it. I want to hear it.

KH: Getting someone to trust you right off the bat is a special skill. It’s the same when you conduct interviews, you have a limited amount of time to make it work. But words are a bit easier compared to being photographed. Letting someone in your space like that, let alone a stranger. Well, that’s a stretch.

LJA: It is a stretch, and believe me, I’m the first one to point that out. No one can just come to me and take my picture, I’m very fussy about that, so when I do it to other people, I know what I am stepping into. When I started out, I was quite shy because I wanted to get as close to these people as possible and not just take a photograph—I wanted to see into their soul and capture that. But it’s like anything else in life. You live and learn; you work through obstacles and one day you get there.

The main thing is respect. Getting into someone’s space with a camera can be very disrespectful. But I try to be with people. I try to immerse myself in the moment with them. When I take a picture, I’m very upfront, you can see what I do, and what I am after. I want a certain picture. I don’t just want to take a picture of someone, I want more. When you put this in words, it sounds almost above reality. But the truth is, as human beings, when we see each other and there’s something that attracts us, we create moments that can be very brief but also very special.

KH: Throughout the years, even with the rise of the digital world, you have stayed consistent in how you construct and take images. Social media, and also many photographers nowadays, almost work against the real moments you are describing.

LJA: The digital world is interesting. On Instagram, you eat and eat till you’re so full you have to stop. And then five minutes later, you’re hungry again. I like to eat food that stays and nurtures. For me, only a physical photograph will do. I distinguish between images and photographs, and I want photographs.

My greatest fear is to hurt people.

KH: The downfall of analog photography is that usually you can’t see the image right away. You can’t correct it or perfect it. How is it with strangers when you take their picture, and they have no reassurance of what’s there? Do you ever show them the image?

LJA: In the beginning, it was difficult because there was no way of getting it back to them. Now, you can email them the pictures. But it’s very difficult to give back to so many people. That’s why, for me, what I do has a lot to do with trust, because oftentimes they are not going to see the picture. What I tell whoever I photograph is that I am putting them in good company. The company I’m building is one where people are going to like each other. It’s my world.

But I have to say that most of the time people don’t ask for a photograph if they feel good at that moment. Also, I am there with my old analog camera, and I don’t just snap—they understand I come from a different place.

KH: If you have something tangible—be it an image or any other artwork—and if you compare how it feels seeing that work on social media versus seeing it in real life, it’s just a completely different language and longer lasting experience/memory.

LJA: For me, photography has everything to do with the fact that I am able to touch it. It connects back to my childhood and to a box of images my mother kept. Touching those made me curious about what they represented, about the memories they were holding. All these years later, that’s still my main drive.

KH: What comes first when you engineer a photo? Do you see someone doing something and you’re like “Okay, I want to capture this moment,” or do you see a person and you’re like, “Okay, they have it in them. Let’s try and do this.”

LJA: It depends—there are all kinds of moments. If I go to the Easter service in a church, then I want to have it all, like a kid in a candy shop. In that process, of course, I go for the moments that catch me. I can’t say it any other way. Every photographer has something that pulls them in, and I guess that’s why we all manage to create different photographs, many times from the same subject.

You can’t make sure that everybody’s going to like you, but damn it, if you’ve got some skill you can make sure that people don’t ignore you. — David Foster Wallace

KH: Funny you mention church, as one of my favorite images of yours, which might also be one of the oldest, is from a service where you captured all these women kneeling and praying, all dressed in white. And it’s not the religious aspect of it, even though it’s a photograph taken in a church. It’s the holy thing, which is part of many of your images, even if they’re portraits from the street.

LJA: The religious idea that you talk about is actually something I often think about. I’m not a religious person, but it’s true, there’s something holy or, let’s say, spiritual about many moments I see and capture. It might also be the feeling of togetherness, being in the same space at the same time that may evoke that. Just the notion of sharing—whether you share food, stories, or memories, there is always some connection that is built throughout occupying certain spaces and moments together. When you mix all that together, something higher can come out. Not always though, and that’s also OK.

KH: There is this quote from David Foster Wallace that comes to mind. He said, “You can’t make sure that everybody’s going to like you, but damn it, if you’ve got some skill you can make sure that people don’t ignore you.”

LJA: There’s a point to that, for sure. My goal was never to be liked. My goal was always to capture something I saw, to keep that memory alive, to share it, preserve it. And it’s not always good, I have been in all kinds of places and spaces. With people being in different kinds of moods.

KH: You have photographed so many people from all walks of life. What is usually stronger at first sight, personal or social identity?

LJA: To me, it’s definitely the personal identity. What I photograph is also not a type. The encounters are very personal in the sense that I don’t approach someone because I think they’re a type. For me, it’s always breaking it down and going down to the bone. I’m interested in you as a person. And yes, I might have no idea about who you are, but I can see who you present. That to me is exciting, but it’s a very individual thing.

KH: Sometimes it only takes a second and our world changes forever. Was there ever an instance that really changed you?

LJA: There are many. But one of the biggest moments, which happens every time, is when people say, “Yes you can have my picture.” And then they stand in front of me. I’m blown away every time because no one stands the same. No one photographs the same. To me, that’s the biggest thrill. There is something about someone recognizing themselves, and feeling good about themselves. It’s very enriching. I can’t tell you what I take from the situation every time, but you do take something that changes you.

KH: To be honest, we all just want to be seen one way or another. I would assume getting some sort of validation—of you recognizing and assessing their moment as important enough to capture—must somehow feel good.

LJA: So true, and it’s funny because you get a lot of, “Oh no, I don’t look good in pictures.” And I’ll say, “But it’s my job to make you look good.” Hopefully, you start a conversation and see where it takes you. A photograph is a photograph, it’s not something that will feed you, nurse you. But it does give you a good moment and having a good moment with someone is a good thing. There’s also a lot of vulnerability out there, so I really appreciate it when people say yes.

KH: Lastly, what is your greatest fear?

LJA: My greatest fear is to hurt people. I do it—there’s no question about it, but it’s a real fear.

A selection of works by Liz Artur Johnson are now on view in the current Tate Modern collection display.

Credits

- Text: Katja Horvat

Related Content

Editorial Roundtable: EMMANUEL BALOGUN and KK OBI, visionaries of Boy.Brother.Friend

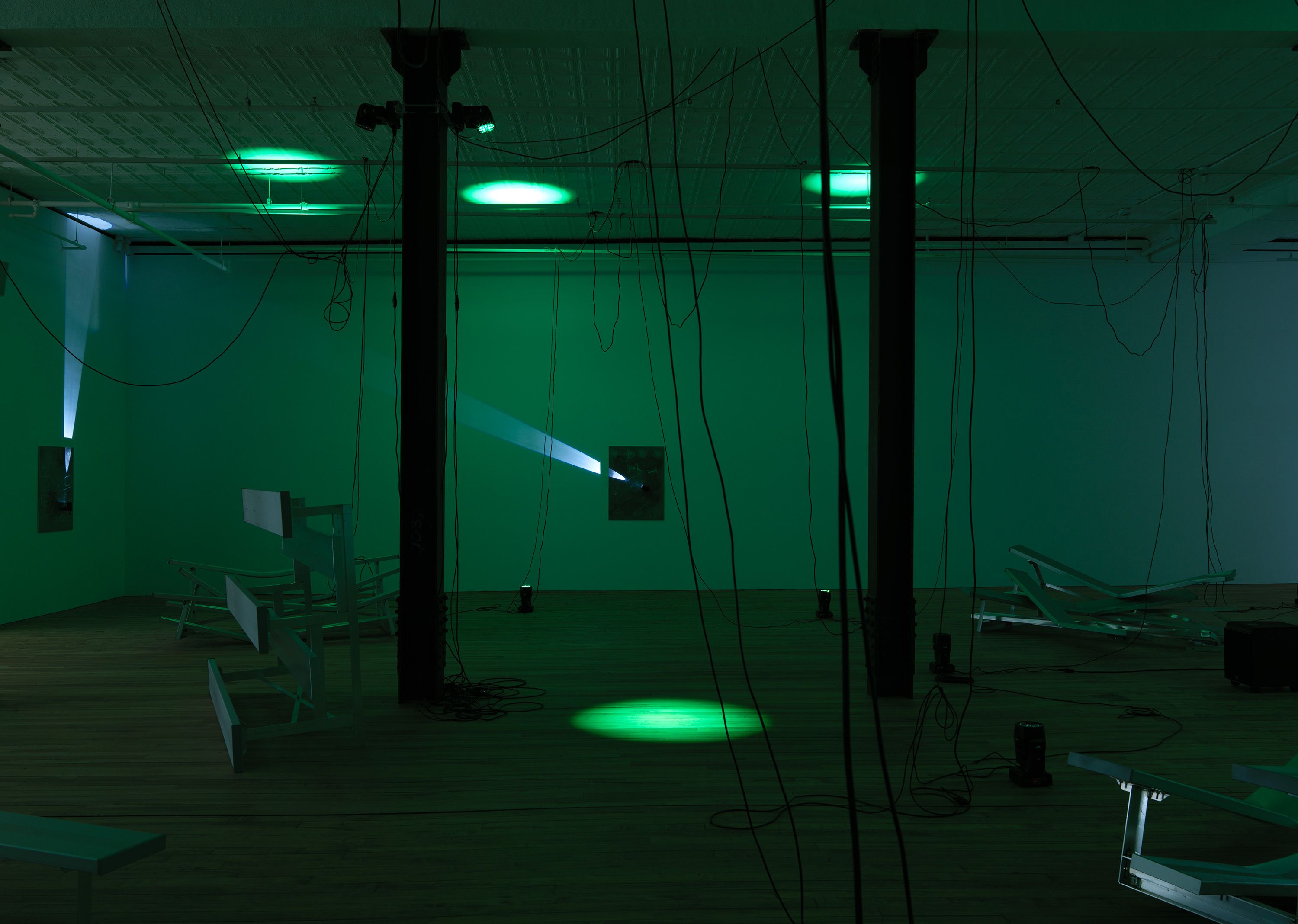

In conversation with EBONY L. HAYNES and NIKITA GALE

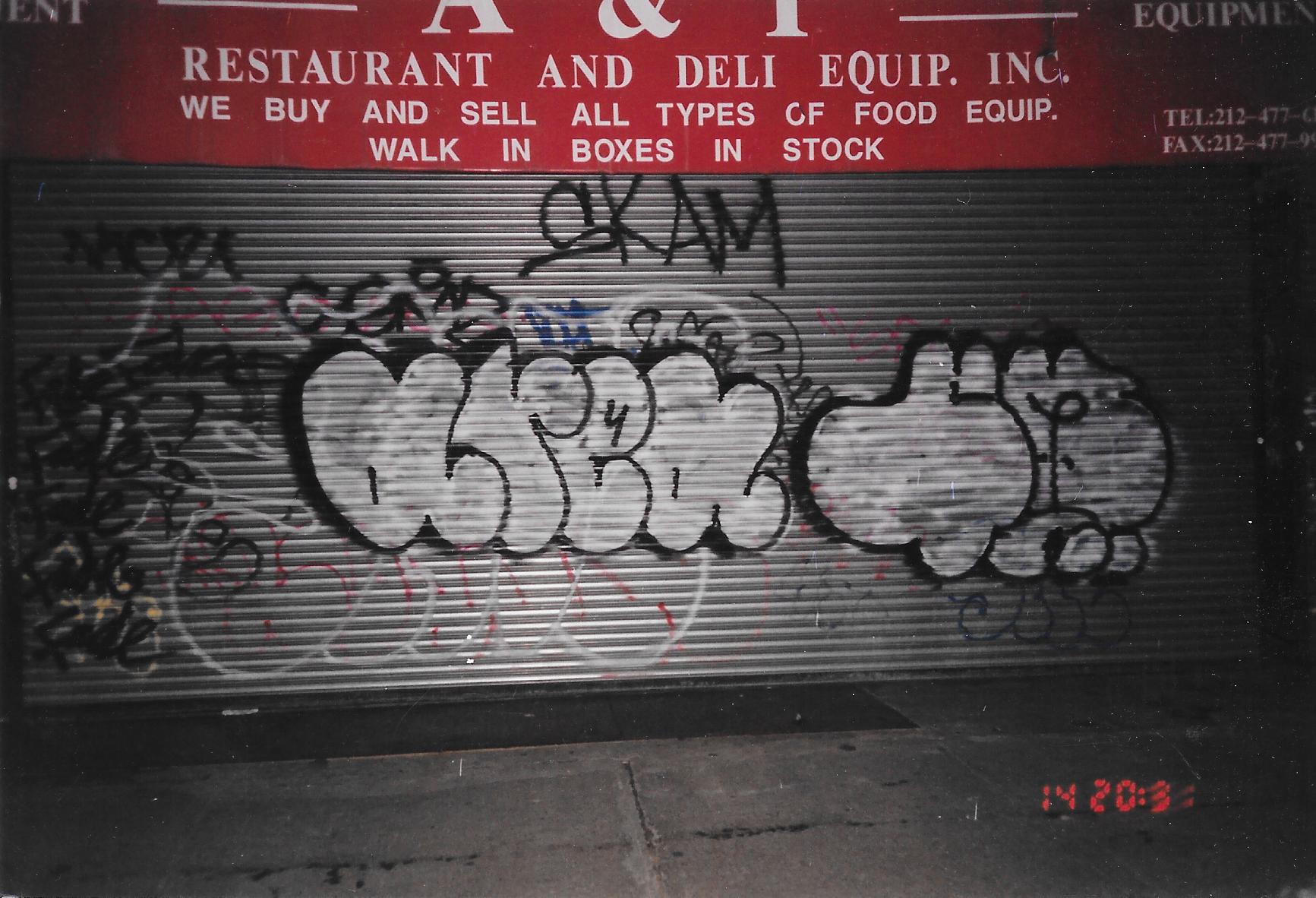

In Conversation: IRAK – KUNLE MARTINS AND BEN SOLOMON

Total Luxury Spa’s LIQUID STATE

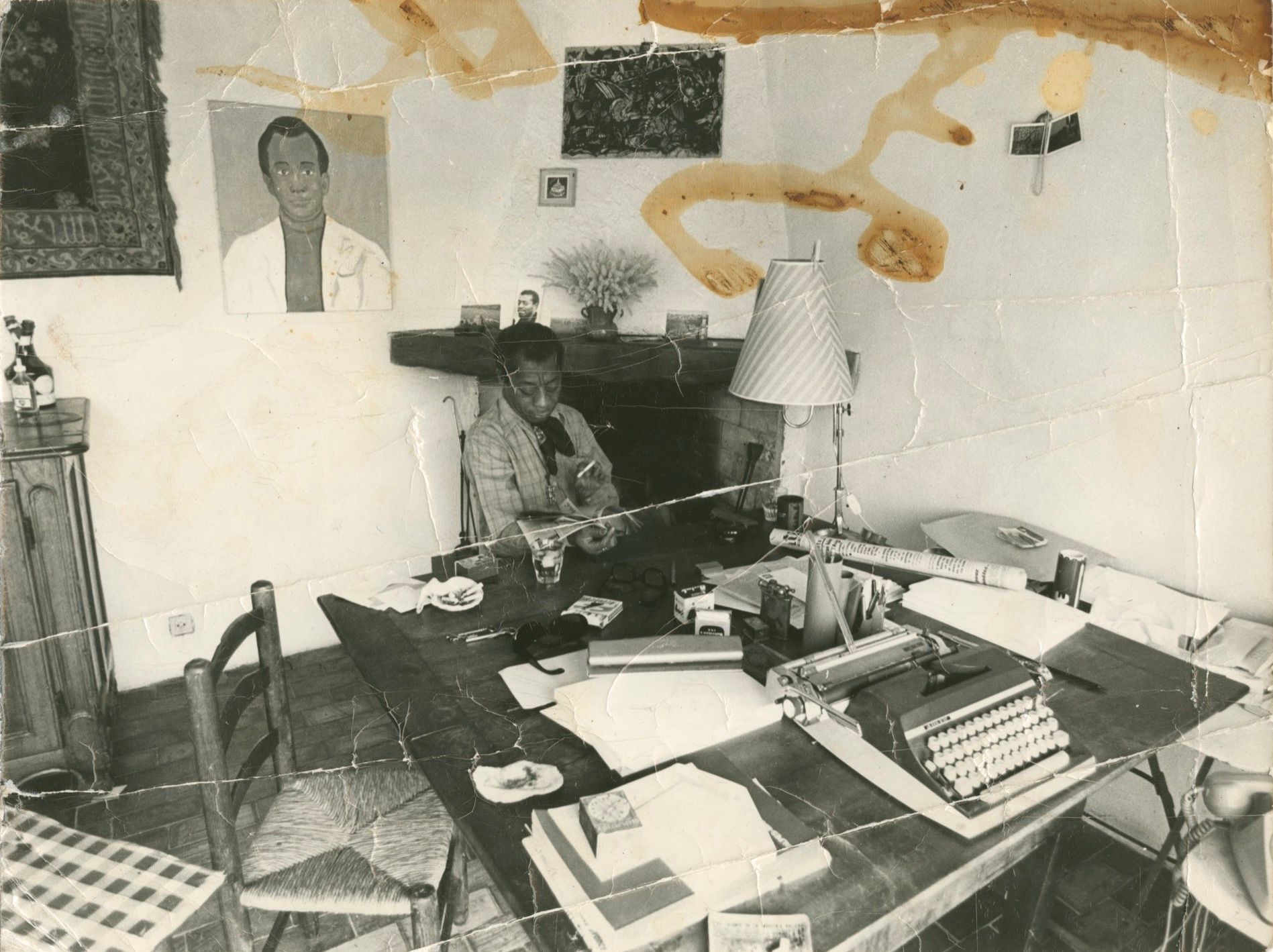

House as Archive: James Baldwin’s Provençal Home

“Sr Jeanne Wavy Boots w. Gazanias and Snails”: Wall-to-Wall ANTHEA HAMILTON for LOEWE Women SS21

Meet SCOTT WATTS: the 21-Year-Old Behind Contemporary-Tech Label gallery909

bLAck pARty