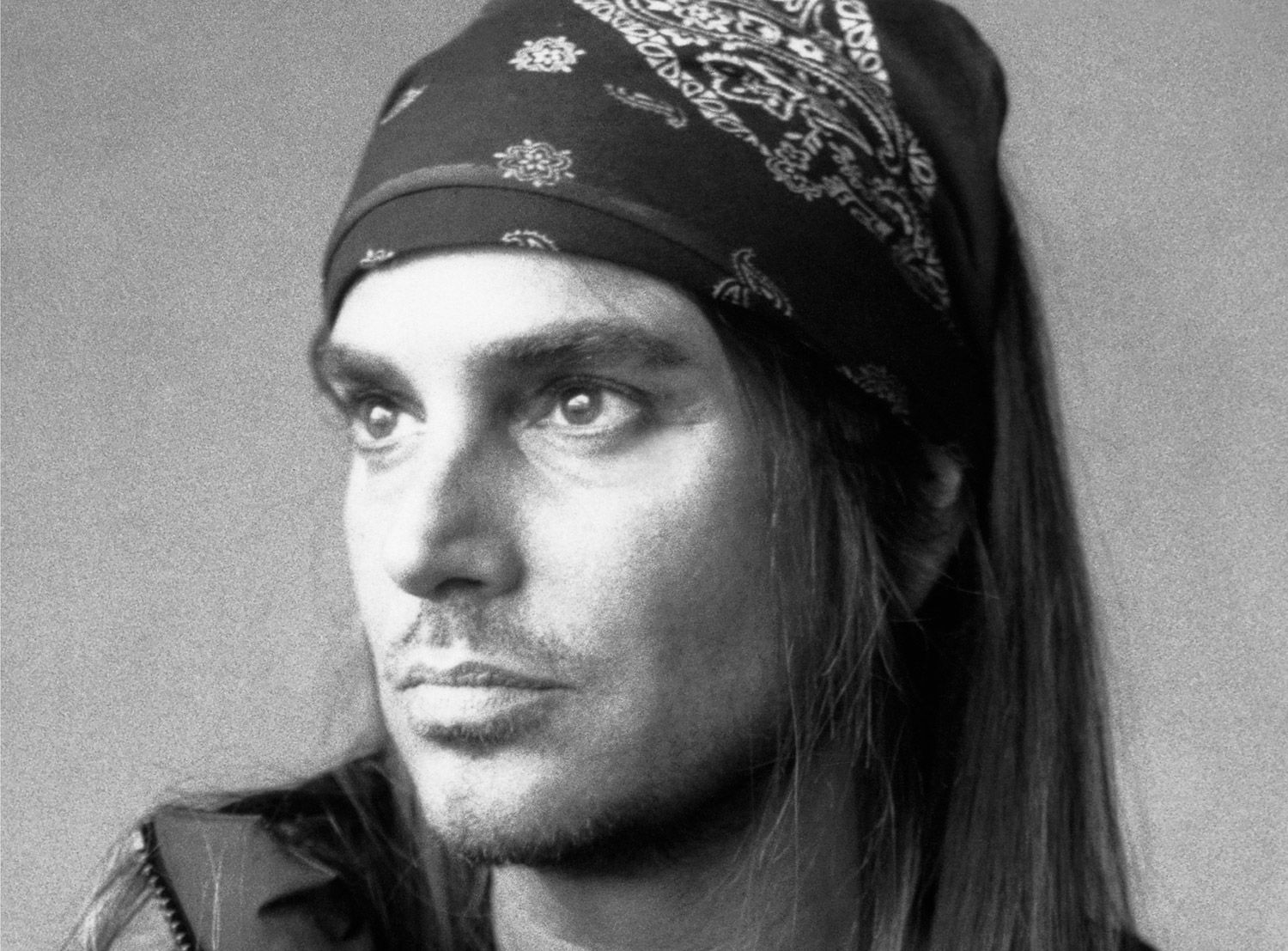

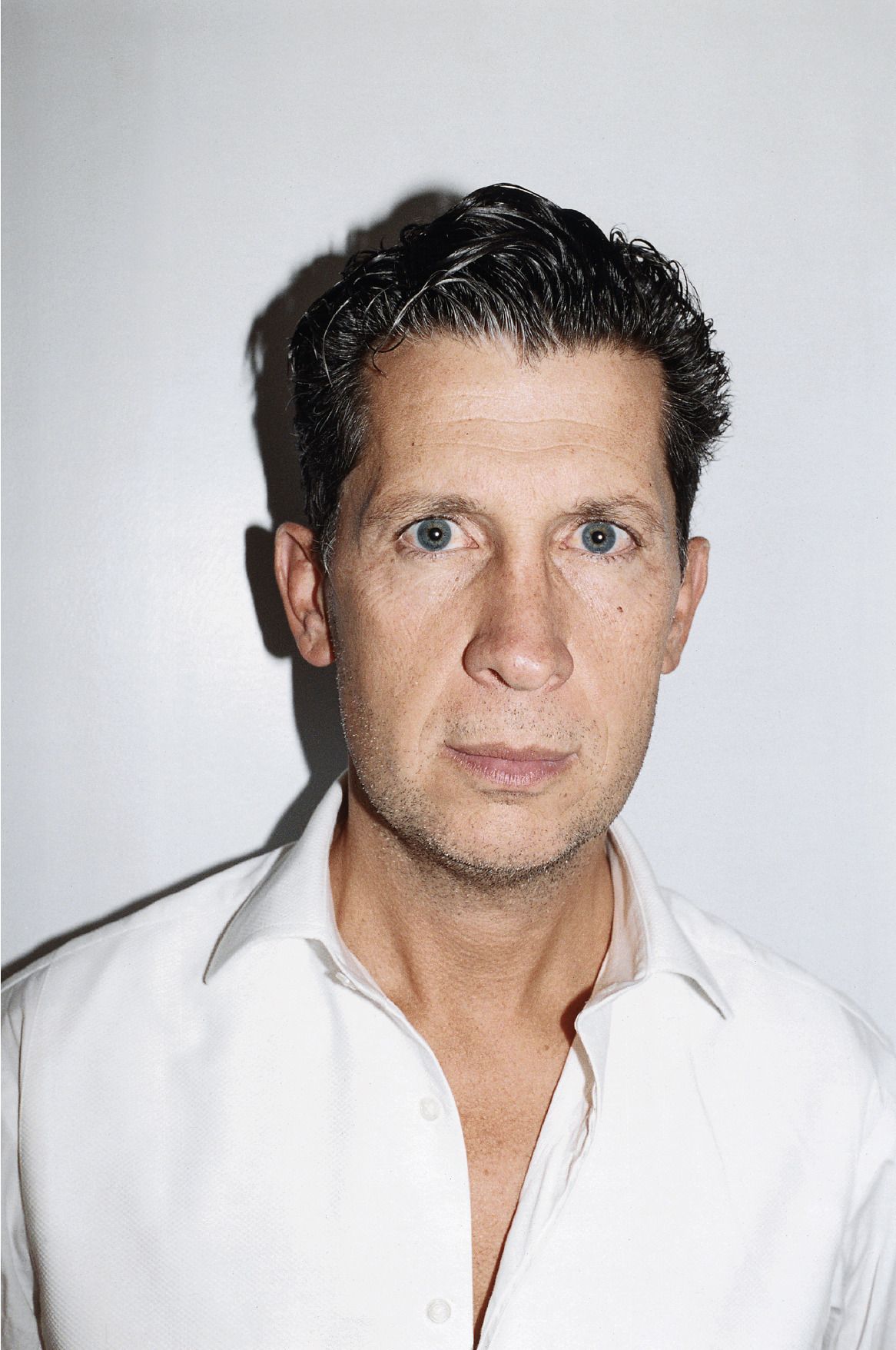

WHAT I DO IS WHAT I LIKE: An Archival Salute to STEFANO TONCHI

|Payam Sharifi

After ten years at its editorial helm, Stefano Tonchi has stepped down from W magazine, disillusioned following Conde Nast’s decision to sell the publication to Surface Magazine. “What is required is a larger vision, a proven track record, international experience, a robust business model with multiple revenue streams, and an ability to anticipate market trends, and ultimately, to innovate,” he told WWD of his departure.

With a CV that includes tenures at Esquire and L’Uomo Vogue, but firm roots in the realm of niche magazines, Tonchi has always been close to our editorial hearts at 032c. Back in 2007, for 032c Issue #14, we spoke to him following another professional milestone: his appointment as editor in chief of T: The New York Times Style Magazine, and the publication’s entry onto the global arena as part of the International Herald Tribune. A lot has changed in the print sector in the last 12 years, but we, like Tonchi, continue to believe in the thriving of our medium – and in its fundamental capacity to evolve alongside digital technology. As interviewer Payam Sharifi wrote in his introduction to our original feature, back before the great recession and the dissolution of the IHT: “Every so often, a publication comes along and ties up those very loose ends nés art and commerce.” Often, Tonchi has been the editor behind these rare apparitions. Stefano, we salute you!

PAYAM SHARIFI: 032c has always had a particular interest in the sense that some of today’s mainstream magazines are operating in a space that is more “avant-garde” than so-called underground publications are …

Stefano Tonchi: I worked in a lot of underground magazines and publications, but I think there comes a time when you want something different. “Niche” publications, I would call them today, more than “underground.” I don’t think that niche publications are not interesting anymore, but everything is very kind of over-ground out there. I think that what you call a niche publication is something smart, something that is still very interesting and still a way to get into the world of magazines, if that’s what you want to do. What I learned, putting together the magazine I had for three or four years –

What was it called?

It was called Westuff. And it was very much about what’s interesting about the Western world.

But you were currently in the Western world when you did this.

Absolutely. You have to think about the early 1980s – Italy was very insular as a culture. And suddenly, in the middle of the 80s, it was part of a larger culture, a European culture, an international culture. We had a very selected kind of pop culture, and very little music. Until the early 80s, we could not even have concerts, because they were forbidden. So suddenly we got exposed to all this great news, and we wanted to create a magazine that had the flavor of, like, Interview magazine, which suddenly we could buy. But going back to the experience that you gain with this kind of publication, when you have to be the editor, the publisher, the graphic designer, the guy that makes the phone calls to get things from one place to the other, that makes the Xerox and that books the hotel, and writes the headlines, you understand all the different steps that go into a publication. It’s just that there comes a time in your life when you say well, I want to understand how a larger publication is made.

From Westuff magazine I went to L’Uomo Vogue, this large magazine. But in the end it was like, what, a 30 or 50 thousand copy distribution. So I came to the United States and I worked at American Condé Nast, at Self magazine – that was 1.5 million or something like that – and then I worked at Esquire. It was really a discovery because it was, especially at Condé Nast, all about research groups and focus groups and you’d get all these numbers – what sells, what doesn’t sell, at the newsstand, what people want, what they don’t want, do they want blond hair, blue eyes … The Times is a nice combination – it has a very large distribution but at the same time it has a very, very specific distribution: it’s

only for people with a certain education and a certain level of income. Because it’s a newspaper that’s expensive to get, especially when you don’t live in New York – I think it’s 5 or 6 hundred dollars for the subscription. So you have a large audience but at the same time you have a niche audience.

When you think about your first publication, Westuff, you were essentially creating a publication for your immediate circle, your peers …

Absolutely, that’s how you start …

And now that you have a readership of I don’t know how many million, how does that influence, say, the transition in terms of editorial choices?

I have to say, I still kind of follow my instincts. A lot of what I do is what I like, and what I would like to find in a publication, and usually, if I get tired of something, I feel like my readers will be tired of it too. And that’s the way I make a lot of editorial choices. It doesn’t mean that you don’t consider your place in the market, or your readership, or where you stand in terms of a publication, and the things that you can do and the things that you cannot do.

I think to a certain extent, publications embody places. And I think, within our much more globalized world, there is a Berlin ethos with 032c. You know, Paris is throughout the pages of Purple. How much does T convey New York-ness, how important is it to convey a sense of space, for a publication? Or its origin?

Well, T is a very specific deal – it comes with The New York Times. New York is part of its name. But in that sense it’s a very American publication.

More than a New York one?

Absolutely. I personally don’t think about New York as a geographic place. I think about New York as an idea; it is a place of the mind. I really believe this. There are people who are New York in their minds – it doesn’t matter if they live in Georgia, or if they live in California, or if they live in Washington. It’s a liberal state of mind; it’s an international state of mind. Maybe there are more of these people concentrated in New York or on the East Coast or in California than across the country, but it is a very American state of mind, and it’s sad that there are not more of these people. In fact I think T is something that is very much for people that are in a certain state of mind – they like to travel, they are curious, they like to read, they like to discover, they have a certain sense of adventure …

And meanwhile, you are globalizing the T brand. The International Herald Tribune now carries your supplement …

Yes, and I hope the company will keep investing in the brand’s success. We reorganized the calendar: we now have four design issues, four travel issues and seven fashion issues. And the partnership with the International Herald Tribune will allow us to reach out of the States and be really international. People will be able to get T magazine from Moscow to Tokyo, from London to Dubai, the same day as it is published in New York.

You also launched the T website with a big gala in Milan during the women’s fashion week this fall – I even heard people were impressed to see you standing at the door all night, greeting guests. So how is the website squaring with recent brand expansion?

Well I was asked by the newsroom to build a website for T magazine and I tried to create something that you can experience with large images, sounds, and lots of videos and interactive features. We are working with video and film directors like Jake Paltrow and Zoe Cassavetes and with digital artists like Jennifer Stainkamp to define the look of the content that will be specific to the website and different from what you can find in the printed magazine. We are just starting to see if that’s possible for a website that has to be mainstream and user-friendly for a large, multi-age audience.

How do you explain the success of T , both creatively and financially, within the NYT structure?

When I arrived at the NYT five years ago I really believed in the power of newspaper supplements and the staying power of luxury magazines. The NYT did not. They had decided to focus on the web as the future of the company. And they still do so. Following the experiences of European newspaper supplements I believed that the NYT’s

advantage was its very wide, very smart, and very rich audience … but one that is not too jaded like those of other fashion publications. Behind every success there is a business plan and this one definitely worked.

What can be learned from this success? I don’t mean just vis à vis the growing influence of the web – what does it say about doing print magazines in the future?

I have always believed in quality. I came from a magazine background, from elite publications like Vogue and Esquire, and I believed that a larger audience was ready for more quality and more challenges. I always thought about Apple and their products. You do not need to talk down to your audience. Especially if you work at the Times; even more so if, like T, you do not need to sell at the newsstands. I knew how to make advertisers happy and I was lucky to have considerable freedom – I was flying under the radar of the NYT newsroom while they were interested only in web ideas. But the web will not kill magazines. Maybe newspapers, but not in the short term. After all, I do not see a reason why not to work on both sides of the business at the same time. Why leave the luxury magazines business only in the hands of Condé Nast? Luxury magazines will last and will stay successful because they offer something that the web cannot deliver, at least not now. Beautiful images, easy access, and the pleasure and the habit of a whole generation – aged 30 to 60 – who grew up and who lives with magazines. They are going to buy them as long as they live. And they have plenty of money to spend.

So, you have an editorial background, and there’s a kind of drive in publications towards art directors leading editorial charge recently. Is there a threat to text nowadays?

Actually I come more from a photography/art background than from writing and editing. Especially from the moment I moved to a magazine like Italian Vogue, when the words are really irrelevant. So I would say mine is more a photographic/design vision – even the word “vision” says something. You know it’s interesting, I usually do defend the words anyway. I try. When I talk to the art department I don’t always take their side in terms of “less words is

better,” “let’s eliminate the text.” That’s the point that really annoys me. Something that I learned after coming here from niche publications is that the primary reason we do this job is to communicate. It’s what we do – whether you want to communicate to ten, or to a million. You have to make yourself understandable. You can do it through pictures – and I think you can tell a lot of stories through pictures; even putting one picture next to another picture can completely

change their meanings. But usually you have to use words. A good heading and a good text become very important. And usually in niche media, you give so little importance to the words. You make a text completely unreadable: it doesn’t make any sense because it’s written without any meanings, or you use the type just to design. I’m not against type that is unreadable, but then I call it a design page; I don’t call it something else. Those are some of the major arguments I have with the art department or the graphic designers – I’m not somebody that loves their dictatorship, even though I come from that background. In the same way I don’t believe in the dictatorship of photography. At least fashion publications in America seem to place an importance on writing more than their European counterparts …

How do you see the difference between what America expects from a publication, as opposed to your experience with European lifestyle and style publications?

I think Americans expect older journalism and a much more linear narrative than we do in Europe. In Italy, we have a tradition of journalism that’s more, say, subjective, that has more space for opinion. There is a lot of first person, there is much less certainty. Americans look in their journalism for more information and more objectivity. They like direct narrative. You have to go step by step.

How would you translate that into your style?

Well you try to be a little bit more literal, a little bit less abstract. We do it less than other publications, because we have the luxury of not having to deal with the newsstand. That is a huge luxury. But everybody in Europe or in Italy understands that what you see published is more a source of inspiration – not instructions on what clothes to run into the store to buy, for instance. Here it’s much more direct. The information has to be fact-checked; if the reader doesn’t find what you sent him to the store to buy, he’s going to get back to you – if a garment is not available for some reason,

we have to write, “Made to order, this is the number to call.” And in that sense I think about certainty.

“We like to say that fashion is the closest thing to a “mirror of society” – just because then you have to justify everything that happens in fashion with some social of political reason. That is not true. When you think about fashion and contemporary society, fashion is a mirror of it – but a mirror in the mood, a mirror in the atmosphere, a mirror in the sensibility. … That doesn’t mean that the skirt gets long because the economy is bad – that’s really an old way of reading fashion to make it more relevant than what it is. That’s not the thing. Fashion expresses the mood of people much more than other media.”

Would you call that rigor?

It is. And I see in this certainty a kind of honesty.

I feel that in T, there is a drive towards sincerity. Before, let’s say ten years ago, I felt there was always a little bit of distance, a bit of tongue-in-cheek. Sophisticated, but it wasn’t taking itself seriously, because it was dealing with fashion, which was not considered “serious.” And I feel that there’s a deliberate thing, that there’s a drive towards sincerity.

There are no justifications for doing fashion. You take it seriously, you look at it – it’s not a cynical kind of approach in that sense. It’s from people that like fashion, like design, like travel, and are quite aware that there are a thousand things that will pass by but the moment you are there, you believe in it. And in that sense you could call it a sort of honesty, a certain sincerity, absolutely.

Do you think there’s a certain amount of uncovering the meaning behind what people don’t ascribe meaning to? A lot of times people tend not to think of fashion as having a discourse …

We like to say that fashion is the closest thing to a “mirror of society” – just because then you have to justify everything

that happens in fashion with some social of political reason. That is not true. When you think about fashion and contemporary society, fashion is a mirror of it – but a mirror in the mood, a mirror in the atmosphere, a mirror in the sensibility. It’s a mood mirror. That doesn’t mean that the skirt gets long because the economy is bad – that’s really an old way of reading fashion to make it more relevant than what it is. That’s not the thing. Fashion expresses the mood of people much more than other media. Especially at this specific time. That’s why so many great people are working

in fashion, so many designers who have been in many different fields before.

How do you see the specific evolution of fashion and lifestyle, and I would say even moving towards art nowadays, now that art has become more accessible?

Well especially with magazines, we are moving away from simple information and becoming more and more of a very decadent society dealing with the pleasures of life. What is lifestyle? It’s the things that we like to do, the things we don’t consider obligations …

So in some sense it has to do with leisure.

Yeah, I think so. When I think about it I think about the places you want to see and visit, the cultures you want to know more about. It’s the things around you, the objects around you, and you can include clothes there, you can include the home … And that’s what I call the “lifestyle capital.”

If I had asked Tyler Brulé [founder of Wallpaper and Monocle magazines] that question, his answer would probably have included work, obligations – recently pieces are always about airports and workspaces. And it’s interesting because you think of lifestyle as purely leisure … Or does it encompass work as well?

Maybe because I come from a very southern Italian background, I always think the part of your life where you are making the choices about what to do, what not to do, and how to do things is very important.

It seems like the line between work and leisure is very fine in your line of work – how important is the social side of what you do?

Today in our “society of total entertainment,” everybody needs to perform a social role. So, somehow I think about the social part of my life as an extension of my job. I still do have a private life, a family and personal interests. What I mean is that it is impossible to do my kind of job today without accepting to play the social part of it. Do I like it? Sometime it’s a pleasure, sometime it’s a real pain.

How have you witnessed the rise of contemporary art into lifestyle? The circus that is contemporary art fairs, the Marco Polo-esque tours of the world?

I think it’s just another area. Art is what fashion was maybe 20–30 years ago in that sense. It’s a way to express yourself, express your taste. It’s also a way to entertain and enjoy life. In the same way people used to enjoy shopping, now they enjoy going to art fairs.

It’s a different kind of shopping.

It’s a different kind of shopping. And I think it’s kind of interesting because we move to an abstract form – the focus of

what you look at is something much more abstract.

How so?

I mean, through the difference between looking at a very beautiful garment by Gianni Versace, evolving to looking at a

beautiful garment by Comme des Garçons. Moving from a portrait by Julian Schnabel to something like …

Damien Hirst or something.

Yeah, something like that. They’re a different level of abstraction somehow.

Do you ever see your work as an editor close to the work of a curator? Though curating has become promiscuous, everybody’s curating nowadays …

Yes, but it’s interesting to consider curating. Putting together a show in a gallery is very much like putting together an issue of a magazine. They’re similar experiences. You have to rely on the market, and on your own taste, and then on the story that you want to tell. You are dealing with a more abstract kind of story, and you can make your story more abstract in a magazine.

Is that like a theme of an issue?

Not really. Stories come together and suddenly you have a certain mood. But it doesn’t start like that; we don’t have monographic issues. Actually that was something that we did…

Probably a while back? That was very 90s.

Yes, it is. Very 90s, the monographic issue. I don’t think you can do that anymore, the times have really changed in that sense. Too many things go on at the same time, I would say.

“Behind every success there is a business plan and this one definitely worked.”

So how do you define “taste”?

It’s a combination of nature and nurture. Part of your taste is absolutely connected to your upbringing and your geographical roots. You have a certain sense of color; you grow up in an environment with a certain color palette. Grow up in Florence and unless you have some kind of eye problem, you will live in a palette of browns and beige and green. There are no neon lights. You get a certain sense of textures, of fabrics. And if you grow up in the Midwest, you

probably have a completely different sense of color. So you end up with how you put colors and textures together; there is a certain kind of history, and something comes from “nature” – it’s something you cannot really choose. And on the other side, there is nurture. You can develop a taste and work on your taste and decide on the taste that you want to project, and people think that it’s your taste. That’s very much what many people do here.

It’s almost like a layman’s approach to what you’re doing here …

I mean I also kind of hate the definition of “taste,” “good taste” – I find that very boring, when everything is done in good taste, when actually, people that have style make mistakes and they’re not about conforming. It’s about breaking the rules or taking risks and doing experiments and sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t. There’s nothing more boring than that sense of conforming to traditions.

This issue is very à propos given the debate surrounding 032c’s new design. Are “flaws” integral to a real sense of style? Must good design today move away from the so-called perfection of an over-designed environment?

Tradition and good taste are very often the enemy of change and evolution. To make mistakes and to reshape things is a necessary process. Aesthetics are an infinite chain of reactions: minimalism after excessive decoration, dirty and crafty after hi-tech and industrial. Don’t you find it funny to see all these new hotels trying to look like old castles and dusty English clubs after the over-designed Schrager/Starck hotels of the 90s? Graphic design, furniture design and fashion design are just mirroring our social and cultural processes.

Credits

- Text: Payam Sharifi

- Photography: Juergen Teller