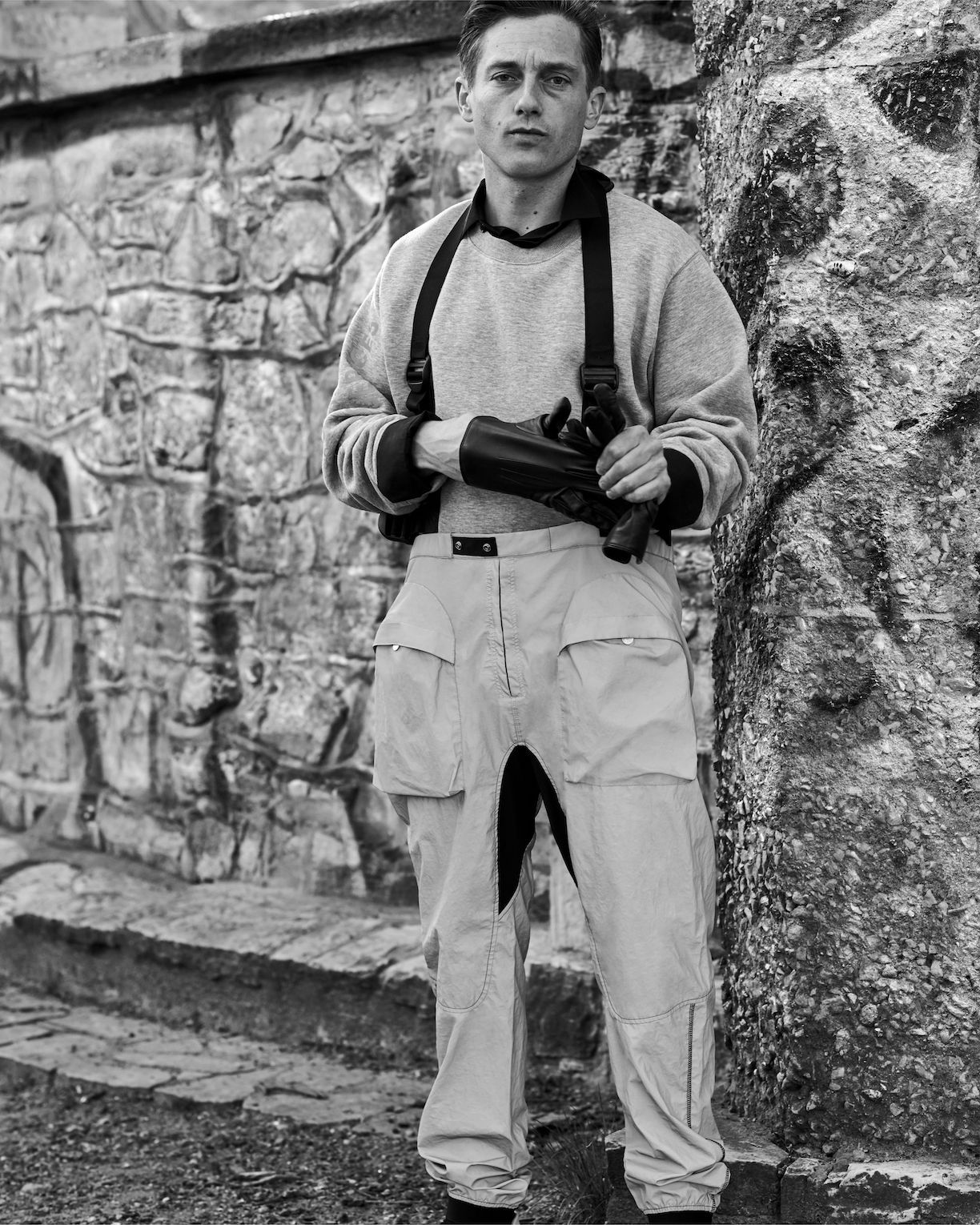

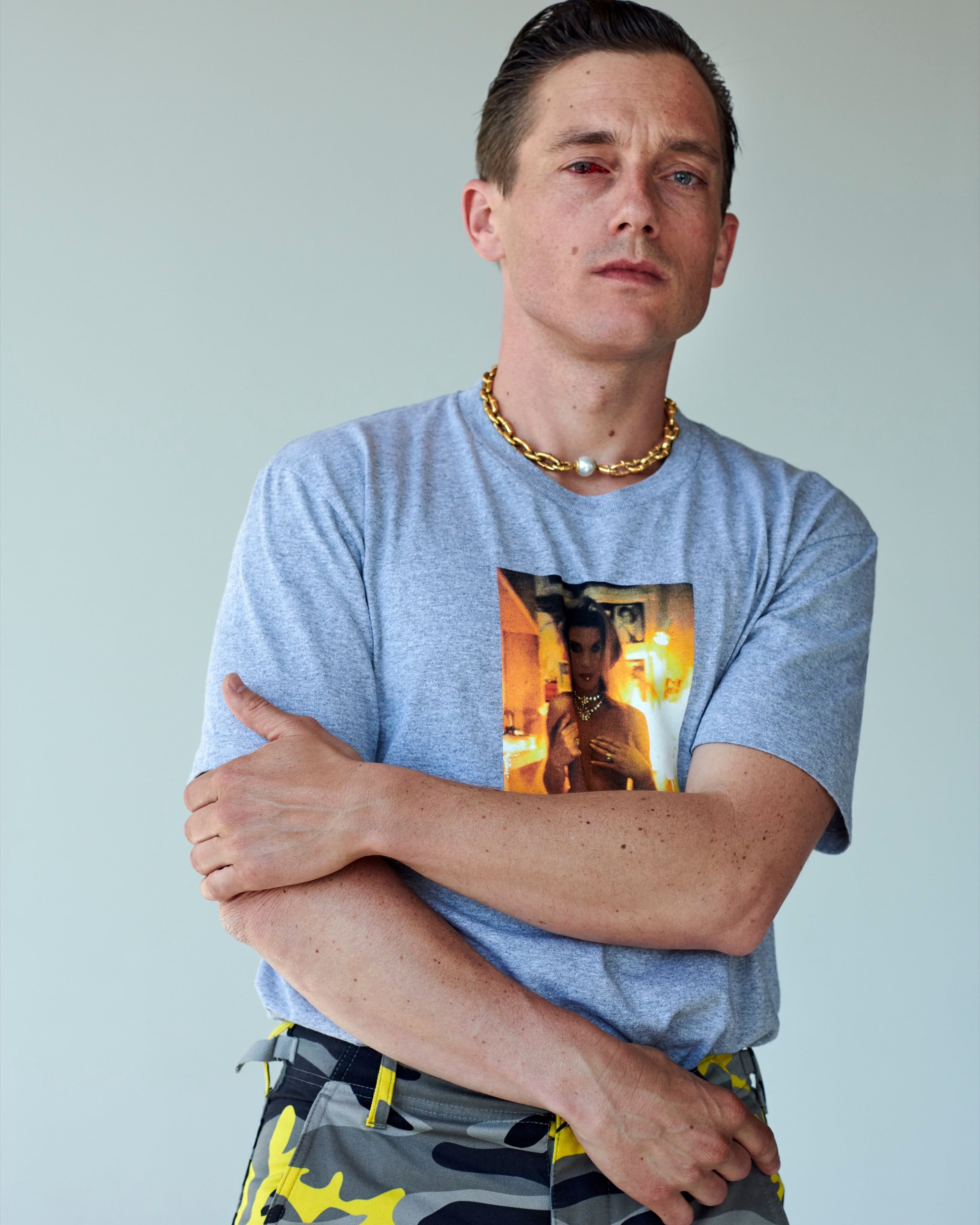

Volker Bruch, ANTI-HEARTTHROB

|Eva Kelley

In the police headquarters Rote Burg [“Red Castle”] on Berlin-Alexanderplatz, Commissioner Gereon Rath moves his flinching body down a long wood-paneled corridor. Every forced step saturates the gray-yellow beneath his eyes a tint darker. As he flings open the green door to the men’s bathroom, his sweat-drenched hand reaches for the aluminum case of morphine phials in his breast pocket. Rath then seizes, convulsing on the floor of the stall, hands pressed on the cold tiles, unable to grip the remedy that remains packed close to his heart.

In Tom Tykwer’s television series Babylon Berlin, currently showing on German TV channel Das Erste, Rath’s body – inhabited by actor Volker Bruch – is a microcosm of a city suffering from PTSD. Set in the late 1920s, the show’s universe is complex and moody, depicting a world between wars. Political fringe groups were gaining momentum, the far right and the far left. Berlin was a ticking time bomb. Seeking a cure for their restlessness, a generation of postwar insomniacs flocked to clubs like Moka Efti on Friedrichstraße, watching cabaret stars in drag perform a capella revues and scarfing down frozen octopi.

Nearly a century later, Volker Bruch sits four kilometers from this bathroom stall in Berlin-Kreuzberg, and is finishing his double espresso macchiato. His headquarters at the Rote Burg is now a large shopping center. Bruch, whose relaxed posture and dirty blond hair are a stark contrast to his character’s appearance, has been featured mostly in the German film world since graduating from the Max Reinhardt Seminar in 2005. He has just returned from California, where Babylon Berlin was released last fall on Netflix US to critical acclaim.

Is it strange to be more famous in the United States than in Germany, your home country?

Fame is not a value that is measurable for oneself.

Bruch’s soft demeanor is often broken by sudden jolts of intensity. He stares directly into my brain through eyes framed by hazel lashes, head tilted slightly downward. My mind dizzies. I am at lunch with the anti-heartthrob.

What we are occupied with in the present are relationships, private things, selfish things. To most people, falling in love or breaking up is so much more important than the outcome of an election. But in 100 years, nobody will be interested in who I was dating.

If you could time travel, where would you land?

We lean toward romanticizing timespans. Perceptions are always very emotional.

In the first scene of Babylon Berlin, you are being hypnotized.

My character’s inner demon receives attention there. At that time, most men over 30 had fought in the First World War. Many were traumatized, they couldn’t cope. They would shake, their bodies unable to control themselves. The psychiatric facilities were overflowing with soldiers and the general opinion was that these men weren’t “man enough” to serve the German homeland.

Have you yourself ever been hypnotized?

I find it very interesting, especially NLP, neuro-linguistic programming. You feel like you’re having a normal conversation, but there’s a subliminal message you’re being fed.

It is a stormy afternoon and Bruch has arrived early to avoid the announced downpour. Still, he wears shorts. In Babylon Berlin, the pained will to oblivion in his eyes comes through in even the most pixelated stream, but in reality, he is mysteriously zen. I wonder what Bruch would look like after being in a fight.

Why do you prefer film to the theater?

I am fascinated by so many adults working toward crafting a moment. The unconditional attention of 50 people on a set, that’s incredible. It’s magic. It’s about life and death in that moment.

Did you have a backup plan?

No. Never.

Credits

- Text: Eva Kelley

- Photography: Bruno Staub

- Fashion: Marc Goehring

- Grooming: Patrick Glatthaar

- Digital Operator: Nicolas Schwaiger

- Photography Assistant: Simon Screiner

- Styling Assistant: Eleftheria Orfanidou