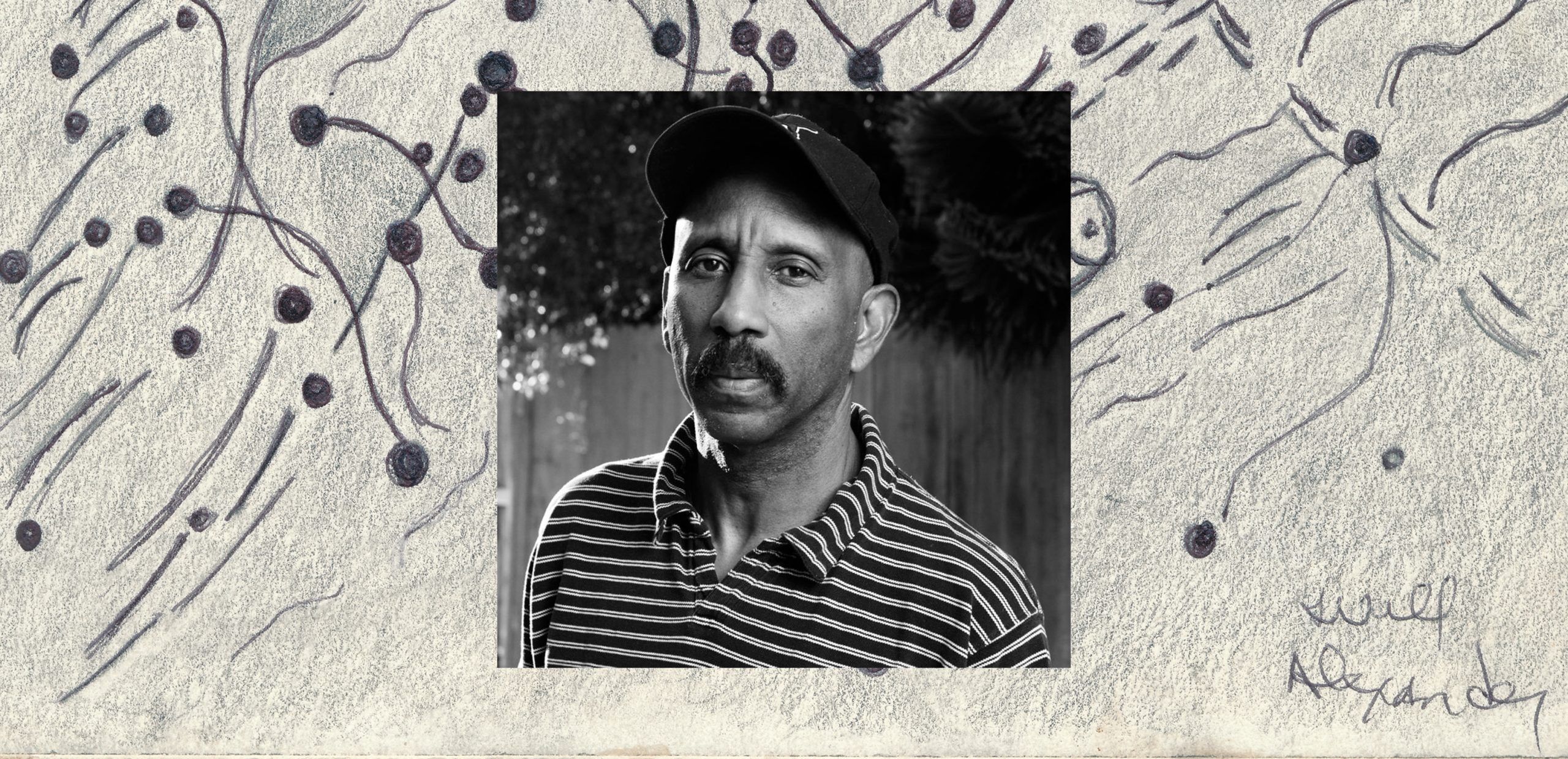

The Divine Purpose and Visual Ministry of JAMEL SHABAZZ

| Olisa Tasie-Amadi Jr.

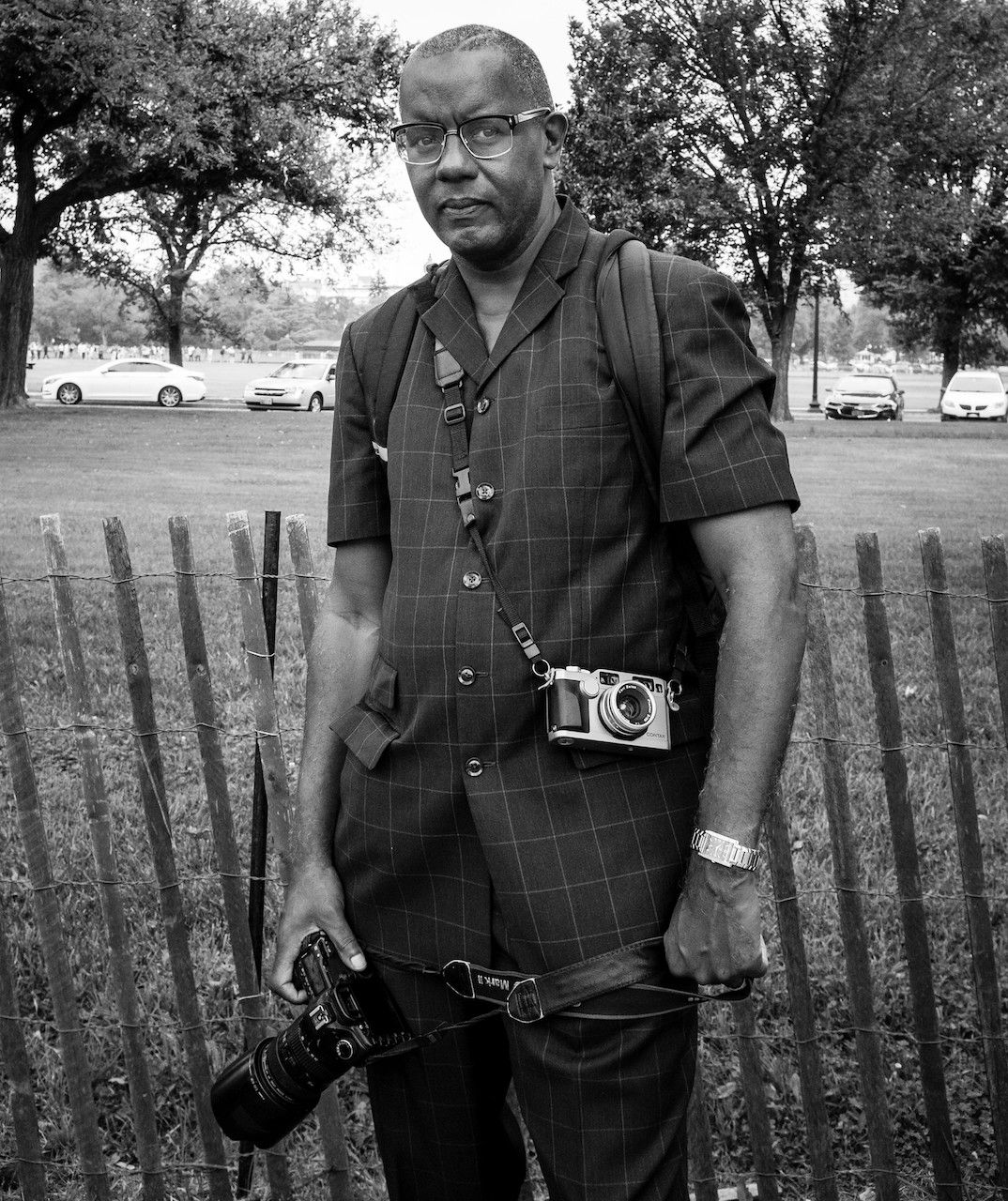

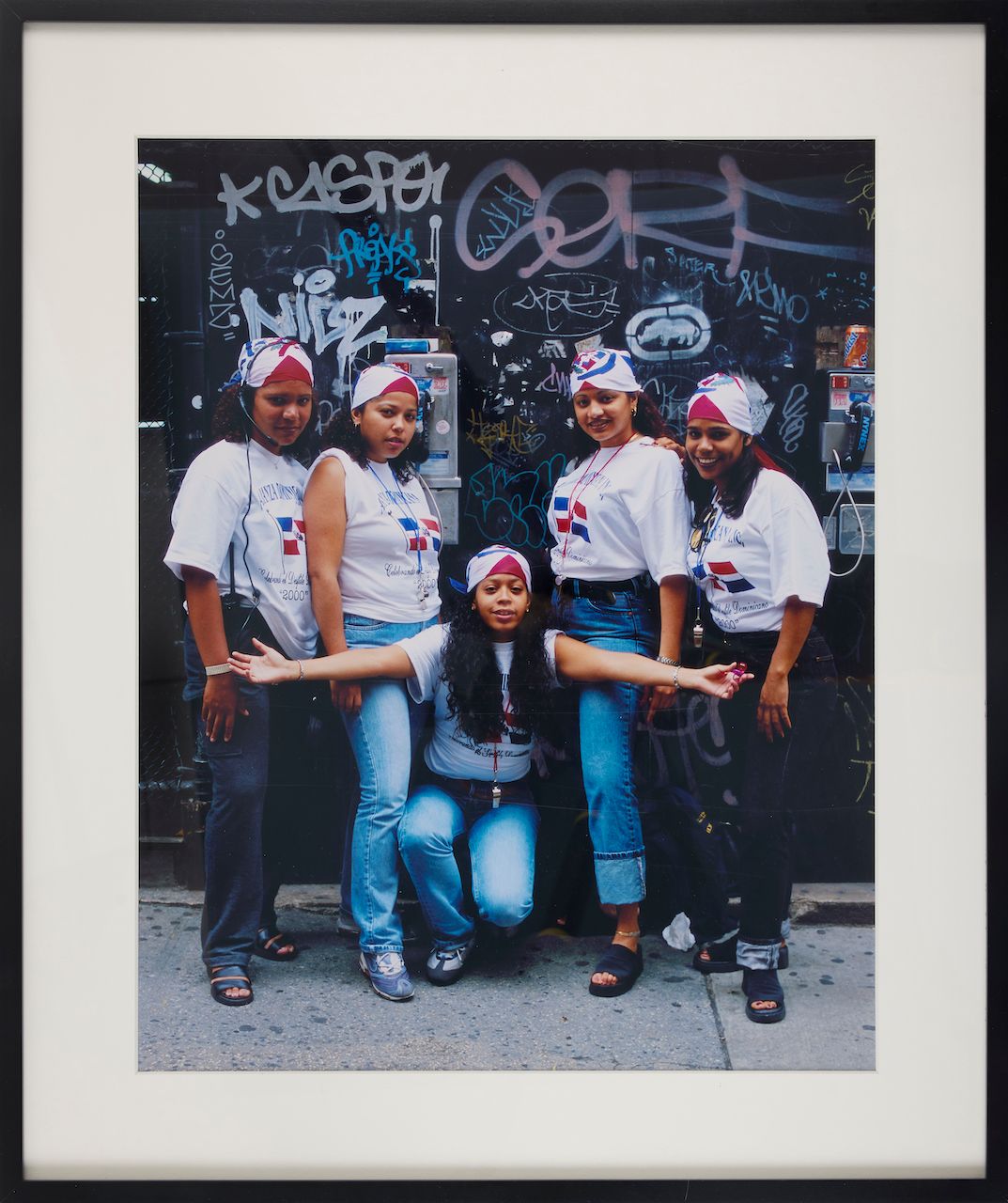

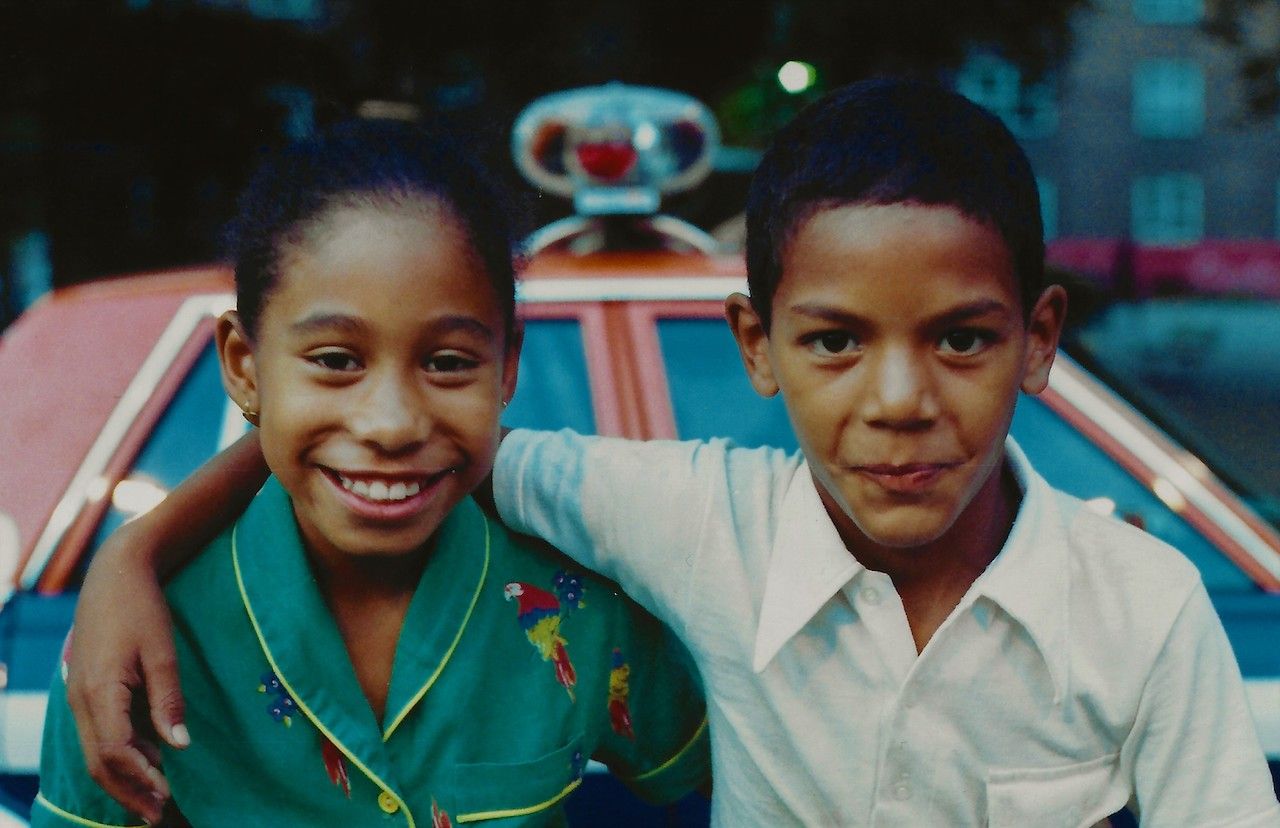

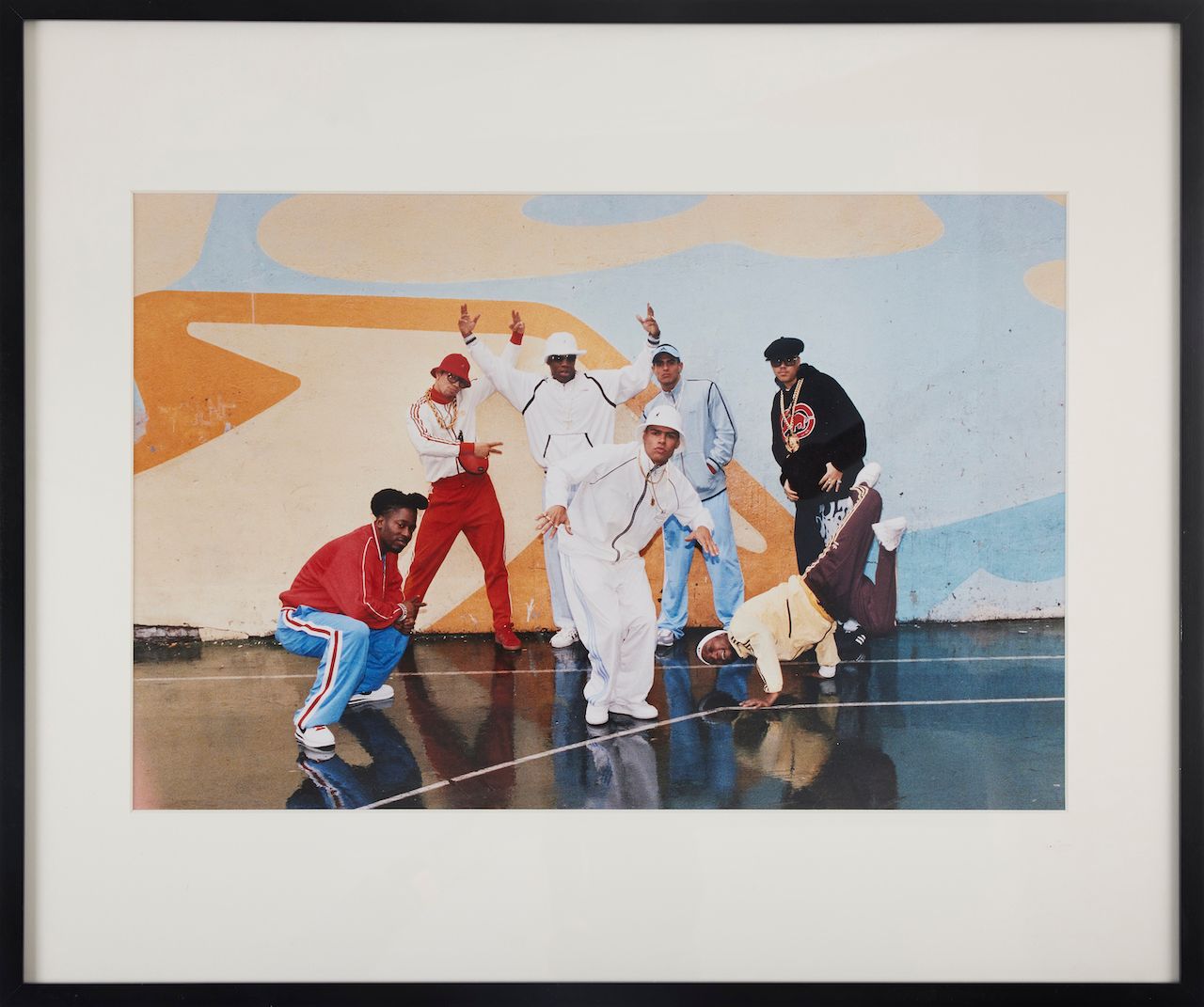

Every so often, you encounter an individual whose very presence triggers an unprecedented helix of enlightening emotions and newfound perspectives. For me, that person was the Black visionary, alchemist, and image-maker, Jamel Shabazz. From photographing antiwar protests and impoverished communities to fashion moments and street engagement, the legacy of Jamel Shabazz paints itself as an everlasting offering to humanity.

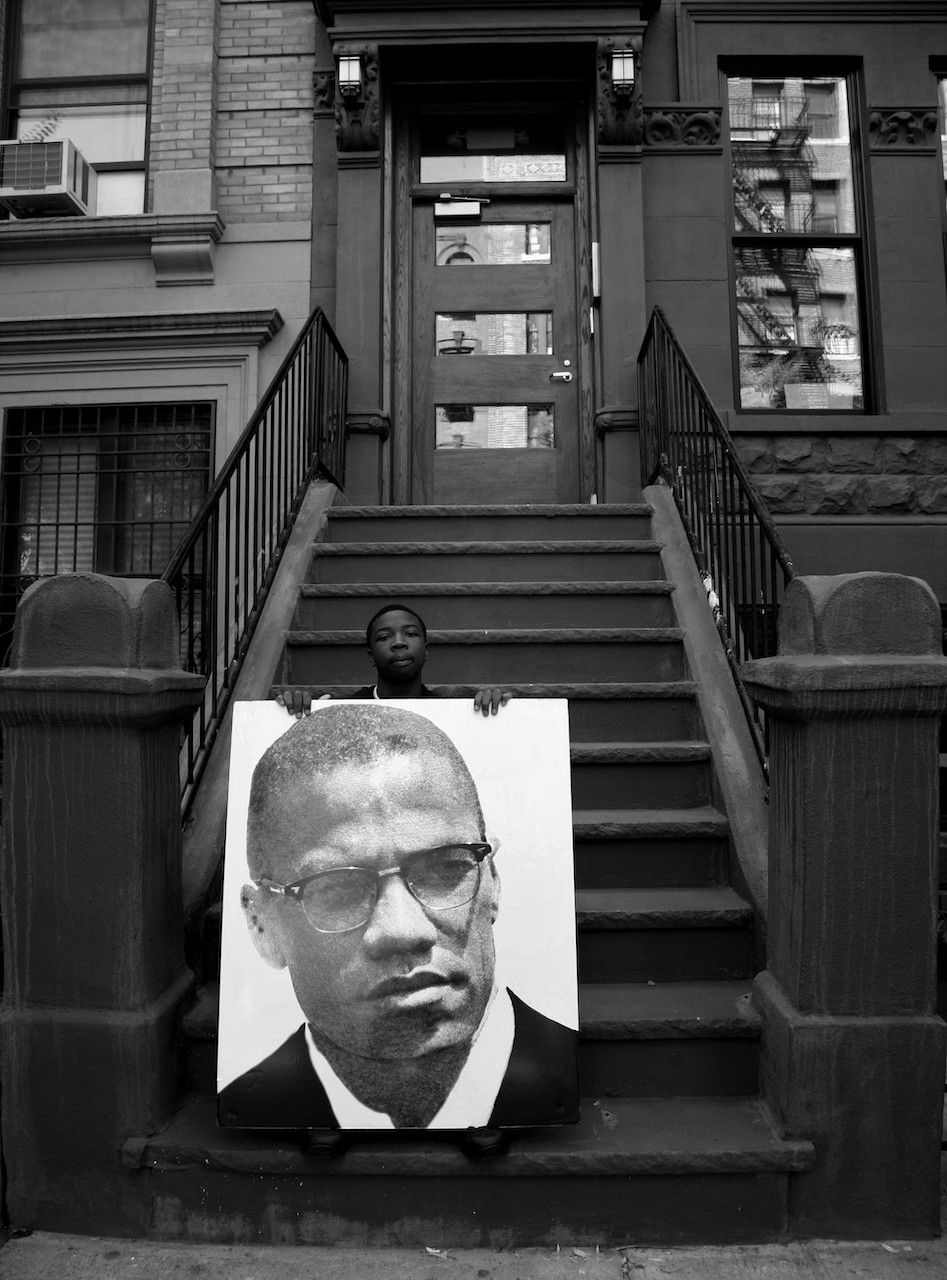

Becoming a symbol of conscious thoughts and engagement soon became Shabazz’s pivotal role within his community. Whether it came from the words of Malcolm X or the sounds of Earth, Wind & Fire, the influential photographer conjured a new form of his craft that went beyond its traditional conception and into a divine voice, solidifying the idea of photography as a form of enacting social justice. “I feel I have a responsibility as a conscious artist to use my position to document life with the idea of preservation of history and culture. It’s become much bigger than I am now, and so, I’ve become that filling in the gap through my work.” It is fitting then, this spring, that the New York native is set to present a newly curated collection of works that explore the abounding retrospective that his 40-year career has so intricately captured.

Olisa Tasie-Amadi Jr.: How do you feel about being referred to as the accidental pioneer of fashion or street style photography? And what has been your response to that title?

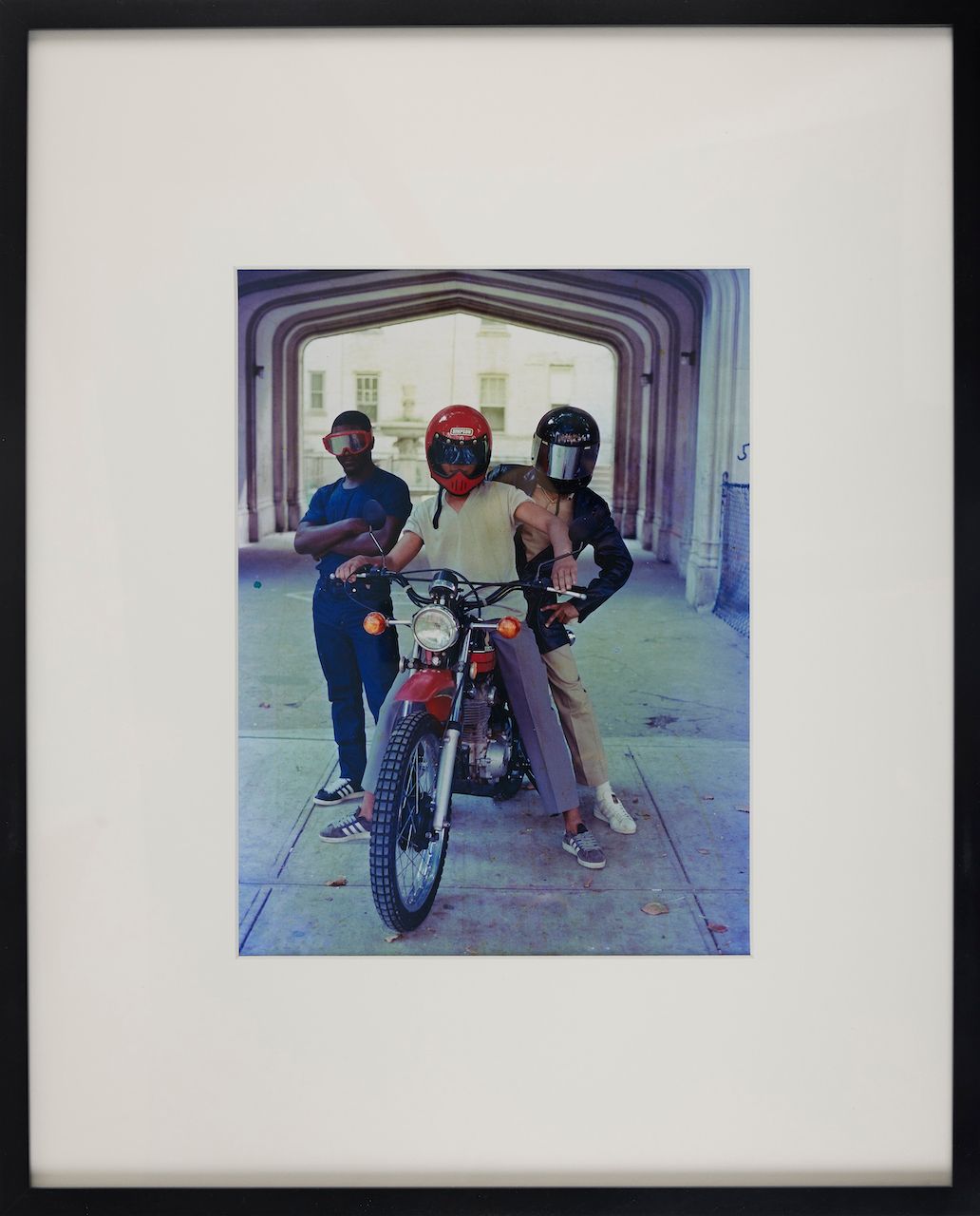

Jamel Shabazz: I appreciate that, though, my work has been about a lot more than that. It’s more about redeveloping a visual diary of my journey, connecting and engaging with young people in the streets, and speaking about the times we live in. When I came home from the army in the summer of 1980, there was a warzone where a lot of the young men were fighting and killing each other, so I felt that photography put me in a position to engage with young people. It was about photographing them, recognizing them, and having that needed conversation with them—that’s what my work is really about. I want to be known as more of a documentarian of our culture and our history, but yes, I do a lot of everything like fashion and things of that nature. Mainly, I contribute to the preservation of our history, in addition to being known as a good person and a good brother who just happened to have a camera. Speaking on the fashion aspect, my decision to shoot fashion allowed me to open doors for young brothers and sisters, so I volunteered to photograph them to build up their portfolios. When I took on jobs, I agreed only on the condition that I could bring on my own people. To see someone else elevated is all that gave me joy.

In that same spirit of loving humanitarianism, going back many years, your time in Germany seemingly transformed the nature of your work from its traditional conception of capturing and documenting, into a form of photographic social activism, as you repeatedly speak on using the camera as a way to save our people and unite the community.

It started in 1975, I think after I read an autobiography of Malcolm X, and transformation coursed within me. It was then that I realized that I had a purpose in life — to be a source of light and inspiration — despite the fact that I was only 15 years old, and it so happens that I picked up a camera which then gave me an additional voice. I was given an opportunity to simply speak about life and what we had to do to move forward as a people. I grew up during a very challenging time. In 1975, something happened and a lot of our parents were being divorced, so as young kids we went and strayed into the streets. At the time, I was just trying to find my way, and lucky for me the library gave me a sense of education and purpose. There was a mantra we were using at the time, “It’s nation time, it was time for us to build a nation,” and for me, I was really serious about it. Thereafter, as I went into the military, my foundation became stronger because I began to learn about the Black Arts movement and the role it played in educating people in various forms: photography, poetry, and music. I wanted to be a part of all of that. When I had these conversations, a lot of the brothers back then were very open to listening, and we would talk about all that was affecting us and how we had to stick together as one. Then, I’d take a photograph and that became the evidence of the conversation.

Going back a little bit to January 1977, news came on television, and it caused this massive transformation where a lot of people were growing into a massive space of consciousness, love, and respect for one another. Then one day, things started to change. Drugs started coming into the community, so I came home and I was pained from what I was seeing. I had to make a change. Not only was I rolling with my camera, but I kept my books and my chessboard with me. I just needed to engage, and in a sense, develop leaders because I needed help too. There was work to be done. With my photography, I would document a lot of the social conditions like prostitution, homelessness, mental illness, and I would put all these images in my portfolio, and as I traveled around, I would show my work to the people I met in the streets so we could speak about them and become more aware of what’s going on around us, and what we need to do about it. That’s how my camera became a microphone … a voice with purpose.

Thus far, hearing you speak on your work, your interpretation of it embodying a missionary-like charge with the goal of unity and change poses a subtle contrast to the parts of your work—the fashion, the hip-hop, and the documentary—that have been more spotlighted in the recent years, which creates an idea that points to a disconnect between what you set out to convey and what is being absorbed by the larger society. On the other hand, it does greatly point to the apparent diversity of your audience. Would you say that is a fair observation?

It’s solely a matter of interpretation, and as I was listening to you speak, I have to admit I do look at my work as a visual ministry. It is truly a ministry and far beyond just making images. However, it all comes down to perception. What I’m trying to do now, through my social media feed, is give people a broader understanding of what it is I do by incorporating music into my images. Oftentimes I’m pigeonholed into this genre of hip-hop photography, even though I deeply appreciate it because of the good foundation it has built for me which has allowed me to travel into the hip-hop circles. Now I show people how I can incorporate a song with an image, presenting you with a deeper understanding. For example with Sights in the City by Guru, there’s a message within every image that goes along with that song.

The music allows me and the viewers to tap into a different sense, and at the same time, it allows me to draw all kinds of people in, from the fashion lovers to the documentarians, from the photographers to music fans, and it’s all good. I want to be able to inspire them. So for me, if you can look at my fashion work, and say I want to be a fashion photographer because of that image, then I have achieved an objective. Some people aren’t ready for my social-like work, so if you can appreciate the fashion photography first, that’s a good stepping stone. As you get deeper into studying my work, then your curiosity takes over, and from that, the evolution within that person begins in the same way I had to evolve in myself and work. I embrace what people feel about my work but I also value clarity which is why conversations are necessary.

You’ve stated that your father taught you the value of themes and applying them when you go out to shoot. On the nature of your approach to shooting, was every day carefully detailed in planning or did you rather shoot in a free-form, go-with-the-flow path, letting the themes and your heart guide you?

It’s a combination of things but there was always a strategy. Before I would go out, being a military man, I would look at it as my mission for the day. I’d do exercises, research on the weather, look at different locations, look at the equipment I had, and much more. That said, my number one objective was to connect with young people. That’s number one. So, I needed to place myself in situations where they were at. Another objective was that I needed to document the reality that existed: the struggle, the pain, the suffering. Then, another aspect I always looked for was joy. Those key things defined most of my days when stepping out to shoot, and it was always in my mind, also acknowledging that there were things that would obviously happen spontaneously. My eyes were always looking but the themes were already there as I looked around. My camera was always out, never in my bag, and I was never without an idea to shoot.

“One thing beautiful about photography is that it’s a global language bringing light into the world.”

Given the nature of your work, and the connection you’ve nurtured with the communities you’ve chosen to capture, there’s a layer of intimacy and personal relationships with your subjects and objects that goes beyond the traditional realm of photographic work, resulting in a pleasantly inexplicable connective thread of lived experiences, thought, and semi-metaphysical bonds. Would you say that has developed a unique iconography over time in both its visual and narrative aspects?

It’s hard to say, I feel as though the people that know my work understand it. As I mentioned, for me, it’s a visual diary of my journey. I want it to be seen as a manifestation of the things I’ve come across and experienced. It’s all with intention, and I’m living within the quotas of my assignment in life. These are the things that I see every day that I’ve been tasked to freeze in time for future generations. This is not no fun thing for me. Yes, I have fun with it, but I look at it really as a divine purpose and a divine gift of vision placed upon me. I feel I have a responsibility as a conscious artist to use my position to document life with the idea of preservation of history and culture. It’s become much bigger than I am now, and so, I’ve become that filling in the gap through my work.

And speaking on the divine purpose you mentioned, beyond the act of preservation and documentation, would you say that defined the crucial role of photography throughout your life, or did it take on different faces through different phases of your life?

This has been a mission I’ve been on for almost 40 years, but that’s just for me. For my students, I want them to understand what my work does and how they can do the same, and how everyone around them can benefit from it too. It was about photographing, engaging, and defining who they wanted to be as people. In addition to the things I had previously mentioned, photography served as a compass that guided me throughout my life to meet different people that I needed to meet. I might not have understood it when we first met, but then 30 years down the line, by resharing images, I’m reconnecting with some of those people and then the purpose of our encounter is made clear. So for me, I tell people don’t take that picture and keep it moving, take time to connect with that person or help that person if they need it. One thing beautiful about photography is that it’s a global language bringing light into the world.

Prior to our conversation, I was viewing an exhibition, “Young, Gifted and Black,” curated by Antwaun Sargent and Matt Wycoff which addresses a plethora of perspectives on Blackness across various mediums, exploring contemporary reimaginations of what we constitute as portraiture, and intricately displaying a new form of surveying racial identity, culture, and reclaiming the color black itself. You being a Black artist and more, having captured both the culture and community for the time in which you have, how does the representation of Blackness in your work reshape and recontextualize existing notions on how it should be conveyed or captured?

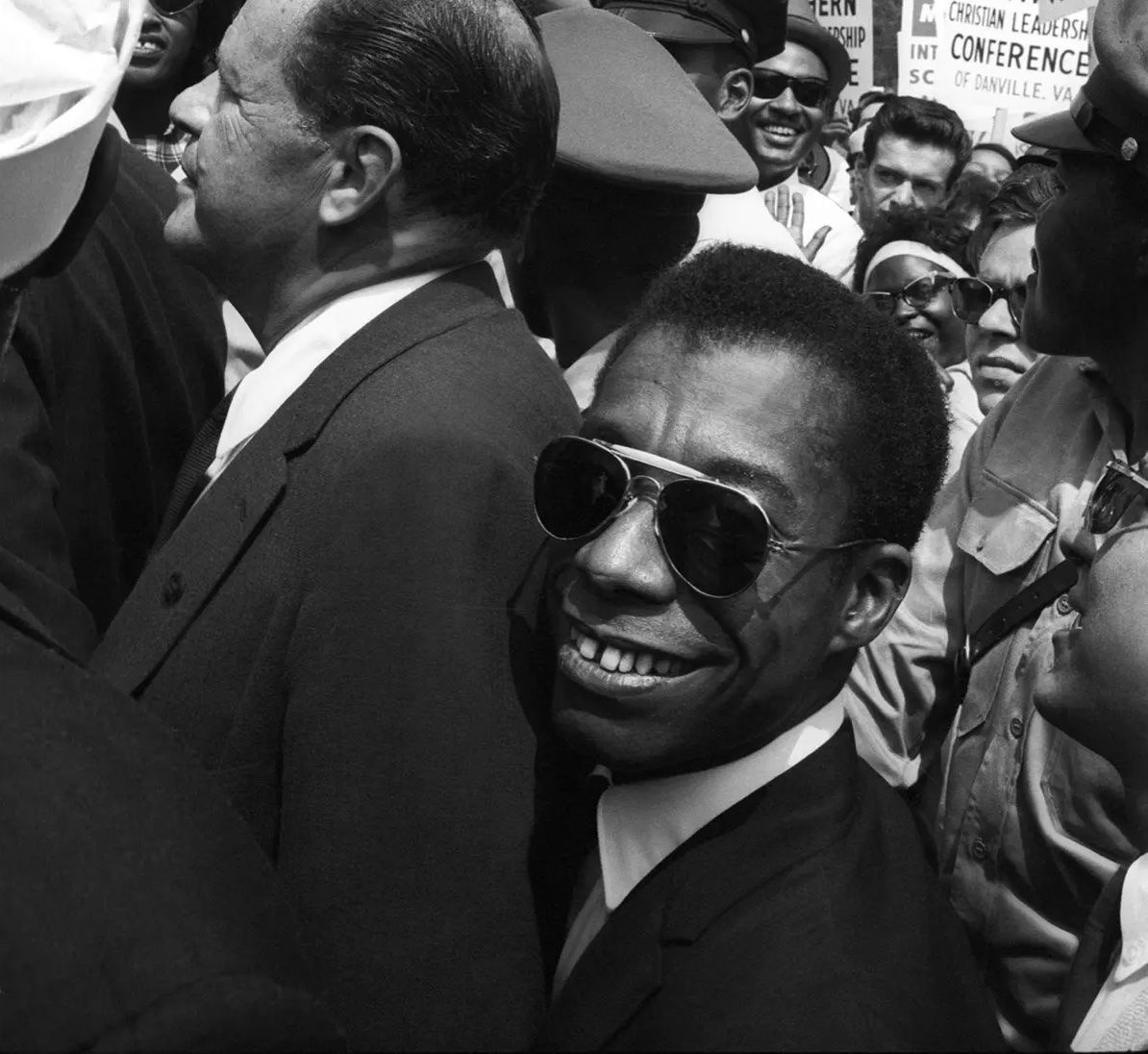

That’s an interesting question because I was just thinking about some of the inspiration behind my work, and it came from W. E. B. Du Bois, as I was studying his Paris exhibition, The Exhibit of American Negroes. The whole idea behind the gathering of those images, during that time, was to help counter the narrative of negative images we were seeing of Black people back then, and looking at that idea I realized that’s something which was important through my work, and even more right now. I look at my work as a continuation of that idea and the impact it could have by breaking down a whole lot of negative stereotypes, so I put a lot of thought into making my images. Right now, we’re being fed with a lot of negative and poisonous images, and I am troubled by that because people’s minds are easily molded and shaped with the things they see day-to-day. So, answering that, I work with great zeal to counter any of those narratives through my life and work. All my shows are very reflective of that idea when it comes to offering evocative and profound images that capture the reality that people don’t really see.

Following that same thought, and on the ability to expand your work beyond what a Black photographer would “normally” shoot, or what mediums a Black artist would usually undertake in their work that align with the western system of thought, do you think your work and that of creatives-alike, can be viewed through a lens not entrenched in identity politics?

I can only speak for myself, and I think that it’s far beyond just Black, which is very important to me too because it’s another genre I’ve been pigeon-holed into—a Black photographer who only shoots the Black community. I’ve yet to show the larger body of my work that contests that idea. One of the things I learned from Malcolm X, because he talked about traveling the world and how that enhanced his understanding, is the need to diversify the body of my work everywhere I travel because that truly showcases humanity. Yes, I want to document my community because it’s where I come from, but also it’s important for me to broaden the scope of what I capture. In the beginning, when I was shooting for companies like Adidas and Puma, they wanted the old-school type of feeling, but I needed to change that. It’s important for me to shoot poverty within a white neighborhood, or anti-war protests and more, and not just protests focused on police brutality towards Black people. During the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, I was out there shooting, and looking at the images you might have thought it was a white man because that wasn’t the type of photography you’d expect from Black photographers at the time. You’d be more accustomed to us photographing stuff that affected the Black community, but I wanted to go against the grain … traveling the road less traveled and really operate outside the box we as Black photographers are put into.

“I’ve put a lot of thought into that process of exhibiting what images need to be seen in order to stimulate one’s thoughts, to captivate them, and to inspire that person to be empathetic.”

On that note, I want to talk about your upcoming exhibition, because no one really knows what to expect, given the vast portfolio you’ve created over the years. Speaking on "Eyes on the Street," what role does the exhibition serve and how would it differ from your past shows?

Firstly, every exhibition is very important to me, and I’ve got like five more exhibitions I’m working on right now. This year has been a really good year for me, and all of the exhibitions, like this one, are designed to serve as visual medicine. I’ve put a lot of thought into that process of exhibiting what images need to be seen in order to stimulate one’s thoughts, to captivate them, and to inspire that person to be empathetic. "Eyes on the Street" gives me an opportunity to showcase new work that I’ve found as I went through my archives during Covid. I’ve found countless images I have absolutely no memory of capturing, and that’s a joy because a lot of it is really under my father’s teaching which at the time I didn’t agree with much. I wanted to photograph more people, but he wanted me to photograph more objects, and that caused my work to evolve. It’s phenomenal because it brings my work to an even more personal level. I’m going to the Bronx too, so I made sure my show would have a great proportion of Latino representation, which is important to me because it allows me to show that I see everyone as much as I see my people too. I want people to look at it and say “wow, I can feel this,” especially during this time. I try to make each show unique, and with this one, given I have more money and resources now, each image is of the highest quality in both printing and meaning.

What are the exhibition's underpinnings most expressed in both its conceptual and visual presentation?

It’s a very vast combination of things, in my opinion. I made it a point to stay away from what people are more accustomed to seeing from me which is more of documentary-style photography. It’s a lot of horizontal references and images, a lot of black and white, and a lot of unposed images that people are going to see. The counter-normative, if anything. It’s hard to explain but it’s just different. The show is also about community and bringing together people around me.

You also curate an accompanying playlist for each of your exhibitions, and as you’ve stated every song you attach to an image must have some sense of searing consciousness and meaning. What does the sonic landscape of this exhibition convey and what might it sound like?

From this point on every show has to have a playlist because that allows me to put everyone on my same frequency when they step into that space, offering stimulation to both the visual and sonic senses of everyone in that room, and with every song, there will be a message to it. It gives a good balance, and I always feel music is that tool that can really touch on a soul and make a person feel good. The music is reflective of the love and the times that we live in right now, meaning you’ll find Marvin Gaye or Earth, Wind & Fire, or simply songs that speak about unity. It’s gonna be a lot of the songs I was listening to back in the day when I had my Walkman on while shooting. Marvin Gaye was reflective of the first few moments I experienced when I returned from the war. Photography is one thing, but the music … the music does something very special.

Reading past articles on your work, the word “nostalgia” is often used when classifying the existence of your work, though I’m opposed to it, given the context. Nostalgia allows us to momentarily relive and experience a moment. However, your work allows us to solidify the existence of a moment in our mind and soul, it’s a timeless sentiment. So, as you continue to photograph, curate—both sight and sound—and explore your divine self-purpose, are there any things from your past embedded in the rediscovery of work?

It’s a lot of pain, I must say. Always pain. Especially at this time when I’ve lost a great number of some of my closest friends. When I’m going through my negatives, I’m looking at people who are no longer here, and it’s very touching in a bittersweet way. It’s bitter that they’re not here, but it’s sweet because I could share that negative with their family, and now it gives them another life of their own, and I feel good knowing I could help with that. That’s why I refer to my work as freezing moments in time because when I then scan the negative and post it to my social media feed, it’s thawed out and given a new life of its own to the people within that photo. It informs a lot of my practices. Sometimes I put up negatives from so long ago, and a lot of the time the people following me have hit me up, and it turns out they are the person in the photo or know the person in the photo. So when I go through my negatives, I go through with great intention to find work that would touch, mend, or move within people’s hearts. I think that’s the joy in rediscovering a lot of my work from the past. That’s why I tell people, when I photograph them, it might not make sense now, but it will make sense later. Every picture I’ve taken has had relevance regardless of how I feel or felt about it.

In addition to implementing your father’s teachings into developing your work, who or what else has offered you inspiration through your life?

Gordon Parks was one of the people who really influenced my work, more now than ever before. Earlier on, I would see his images but never his words. Though, as time progressed, and I would pick up his books, I realized this was a man who went through a lot of hardship, a lot of racism, and a lot of obstacles. Fortunately, he found his way to the camera, and through that, it became his God compass, allowing him to let go of any grudge or malice from the past. He used his work as a way of helping people, uplifting them, and enacting a sense of guidance which really enhanced my desire to continue to do that with my work. Despite the fame, he never forgot where he came from.

I also admired the war photographers and their works, and it made me aware of a lot of the things happening both inside and outside my immediate surroundings. Socially conscious music has also been very instrumental to me during my life because it helped to keep my spirit strong. I appreciate the music of Mos Def, Guru, Gang Starr, Marvin Gaye, and really any artist that produced music that represented the times and consciousness. I also have a great appreciation of Denzel Washington and the type of man he is, and also Mahershala Ali who I find as a very dignified individual in all rights.

There is a seraphic level of awareness and mindfulness to yourself and work, and as a question I want to ask you, directed towards your audience, young kids, and simply people searching for a sense of purpose in life, are there any guiding philosophies you subscribe to in your daily life that you’d like to share?

Confucius made a profound statement that says, “everything has its beauty, but not everyone sees it,” and that is one of the guiding principles of my life right now. Many years ago, sitting on a bus, I met these three young men, and for whatever reason, something compelled me to question them. I asked them what they’d wanted to be in life, and they all said, at the same time that they wanted to be Messengers of God. It did something to me knowing such young men had aspirations above the regular. It became a jewel to me, and this day in my life, I want to serve God and do this visual ministry to make a difference in this world.

Credits

- Interview: Olisa Tasie-Amadi Jr.