Skinny Legend: Ozempic, Body Politics and Unwellness as Aspiration

|Cassidy George

Image created by an AI-image generator, which was prompted to read this essay and then "create an image of a GLP-1 injector for 032c magazine that reflects the tone of the text"

As injectable weight-loss drugs become ubiquitous, body fat is vanishing en masse—along with the body positivity of the 2010s. In a new essay, Cassidy George unpacks the return of the ultra-thin ideal and the enduring link between beauty and suffering.

I.

“If there hasn’t been an Ozempic allegation against you by 2025, are you even hot?” I joked with a friend over text a few months ago. I was teasing him about the rumors surrounding his recent weight loss, but he replied with a screenshot of a group chat from last year. In it, he and his friends had been discussing whether or not I was on Ozempic. “No one can look like this naturally, right?” someone wrote beneath a photo of me. “Ozempic queen!!!” another replied. I didn’t know whether I should feel flattered or offended.

Ozempic is one of the brand names for semaglutide, an injectable drug first approved by the FDA in 2017 for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. It is a member of the rapidly expanding GLP-1 class that now includes Wegovy, Trulicity, and Mounjaro. These medications stimulate the pancreas to secrete more insulin and the liver to produce less glucagon. In simpler terms: they slow digestion and suppress appetite, which can trigger rapid and dramatic weight loss. In 2024, Healthline estimated that 13 percent of American adults had already used injectable weight-loss drugs, a number that is expected to rise. At the time of writing, Novo Nordisk—the Danish pharmaceutical company that manufactures Ozempic and Wegovy—is the second most valuable company in Europe.

Over the past three years, the drug has become increasingly accessible to anyone with disposable income, regardless of health status or weight class, and in the process has evolved into a massive, mainstream cultural phenomenon. Since then, we have collectively witnessed a Great Disappearing Act: bodies have been shrinking drastically, en masse, and with significantly less effort than before. But we know exactly how this particular magic trick is done. By suppressing appetite, semaglutide makes it possible to shed pounds without hunger, deprivation, or the agony of aggressive exercise.

“Oh, oh, Ozempic,” goes the jingle in the medication’s ad campaign, set to the melody of 1975 hit “Magic.” Although Novo Nordisk’s advertisements made their way across major networks, they likely did far less to drive Ozempic’s popularity than media coverage of its use in Hollywood. “Hollywood’s Secret New Weight Loss Drug, Revealed,” Variety reported in 2022. It was just one of countless headlines at the time that linked Ozempic with the rich and famous, which increased its allure in the broader public imagination. This messaging, combined with a flood of homegrown #myozempicjourney content on Instagram and TikTok, helped fuel a massive rise in “off-label” users—that is, users who are not obese or diabetic. Their BMIs already fall within the normal range, and their primary motivations are aesthetic or emotional: they simply want to be thinner.

The spike in demand created a supply shortage, and in 2022, Vanity Fair reported that some celebrities were paying $1500 out of pocket for a month’s worth of doses. Given the correlation between poverty and obesity––and the abysmal state of health insurance in the US––lower-income communities whose health was compromised struggled to access drugs like Ozempic while Chelsea Handler and Scott Disick comfortably stored it in their fridge. The semaglutide shortage ended in early 2025, and costs now vary based on the individual’s location, drug of choice, insurance policy, or method of access.

The idea that getting thin on these drugs is “easy” is, in most cases, a massive misconception. While some people experience few or no side effects, others face debilitating physical––and sometimes social––consequences. Common side effects include nausea, vomiting, stomach cramping, and nearly every gastrointestinal issue under the sun (including, in some cases, fecal incontinence), as well as less severe symptoms such as “sulfur burps,” bad breath, and unwanted cosmetic outcomes such as “Ozempic face” (a hollowed, sunken appearance) and “Ozempic butt” (flat, deflated glutes). The most alarming side effect is arguably dependency. Most people who stop taking semaglutide regain some or all of the weight they lost—and have to stay on some form of GLP-1 indefinitely to maintain it.

The ubiquity of Ozempic has spawned a culture of suspicion and accusation, playing out both locally and globally. Publications like The Cut have treated celebrities’ responses to semaglutide allegations—or their candid admissions of use—like tabloid fodder, with each confession or denial earning its own headline. On Instagram and TikTok, before-and-after photos of everyone from Christina Aguilera to Ariana Grande flood FYPs (some websites even feature sliders so users can reveal the “before” and “after” with a mouse). This cultural compulsion to analyze, assume, and, more often than not, judge, sits in the same Venn diagram as body shaming and body checking.

I wasn’t on semaglutide when the aforementioned photo in the group chat was taken, and I never have been. However, at the time in question, I was profoundly unwell. It was the worst I had ever felt—and the best I had ever looked, at least according to those of us brainwashed by white, Western beauty ideals. There is a simple explanation for this: in periods of great emotional turmoil or stress, I find it difficult to eat or sleep. And yet, I was constantly showered with praise for my body during this traumatic chapter of my life. My size began to feel like the only consolation prize for what was happening behind the scenes. I resolved to enjoy the privilege and had never felt more physically confident or carefree. I knew I would eventually return to my natural base weight, but I found it quietly disturbing that I had never felt more seen or valued than I did at my unhealthiest. Our culture, it seemed, was even sicker than me.

The Great Disappearing Act of the 2020s is twofold. It refers to disappearing body mass, but also the disappearing values of the previous decade. One of the defining cultural concepts of the 2010s was “wellness.” Now, a growing segment of the population––particularly “off-label injectors” who feel ill in their pursuit of thinness and those who admire them––seems to aspire to unwellness instead.

Cover star Gabbriette photographed by Steven Klein for 032c Issue #47

II.

I remember watching Nicki Minaj’s “Anaconda” music video in 2014 and realizing that the tectonic plates of beauty culture were shifting beneath my feet. Minaj’s anthem was formally heralding the newfound supremacy of the “slim thick,” callipygian physique. Shifting body politics were just one node in a broader matrix of liberal cultural optimism unfolding in the era. This was a time when millennials thought putting avocado on toast constituted a culinary revolution, and girl bosses in millennial pink preached corporate feminism. Editors at historically exclusionary publications began using buzzwords like “diversity” and “inclusion.” In America, hip-hop became the most powerful genre in music—and as the notion of “wokeness” spread across media and pop culture, the supposed cultural supremacy of whiteness was increasingly questioned.

In large part due to their appropriation of Black beauty, the Kardashians began to dominate––and dictate––popular culture. A hoard of “aspirational” influencers molded in their image emerged, posting videos of their 12-step skin-care routines between their morning green juice and afternoon Pilates class. Once trendy buzzwords, “wellness” and “self-care” became fully fledged cultural obsessions, fuelling the rise of billion dollar industries. Magazine cover lines changed from “Lose Fat Fast” to “Get Your Glow.”

The fat positivity movement emerged in the late 1960s and early 1970s, as a new tangent under the broader civil rights umbrella. “We see our struggle as allied with the struggles of other oppressed groups against classism, racism, sexism, ageism, financial exploitation, imperialism and the like,” the 1970 Fat Liberation Manifesto states. In the 2010s, social media helped popularize its less radical and more Instagrammable descendent––#bodypostivity––which was diluted and co-opted in typical neoliberal fashion. Eager to cash in, brands jumped on the bandwagon, casting more diverse models and launching campaigns with slogans like “Love the skin you’re in.” Body positivity advocates helped popularize the idea that ideology and culture––not people’s bodies––were what needed to change. “It kind of felt like a renaissance,” model Tess Holliday told The Guardian in a recent article about the declining representation of plus size and curve models in fashion in the 2020s. “Like we were going into this beautiful period where we were at a new awakening.”

Yet, bodies did change in the 2010s—often surgically, or with the help of apps like Facetune. Lips were filled, tummies tucked, hips cinched, breasts and butts augmented and exaggerated. The “BBL [Brazilian Butt Lift] body” became a new status symbol, and the era’s defining sex symbols looked increasingly cartoonish.

Khloe and Kim Kardashian, photographed by Mert and Marcus for 032c Issue #31

Two years after the FDA approved Ozempic, COVID-19 was unleashed on the world, catalyzing countless shifts in discourse, ideology, and aesthetics. Social isolation and incessant screen time gave algorithms more power than ever before. Shaped by a new strain of apocalyptic nihilism that was as contagious as the virus itself, culture became more extreme, more reactive, and, in many cases, more reactionary. When lockdowns ended, Gen Z had come of age and into power, and the collective mood had turned: in general, people of all ages were either angry, unhinged, or giving far less of a fuck than before.

As a consequence, #alt aesthetics started gaining more traction on social media, and rock music began trickling into the pop charts. The spirit of Y2K Hot Topic and mall goth was revived by trendy new fast fashion labels, such as Jaded London and Minga London. While subcultural tropes were co-opted by high luxury, indie looks from the late 2000s were rebranded as “indie sleaze.” Fashion critics linked the style to recklessness and hedonism, an overtly anti-green juice, “messy girl” attitude epitomized by all things “brat.” Club culture exploded and “feral” became chic. Words like “rotting” and “crashed out” entered the lexicon, and a drug-induced (pharmaceutical or otherwise) strain of thinness became glamorous.

Along with it, a new vanguard of it-girls rose to power, including 032c cover star Gabbriette. Dazed Beauty reported on the rise of “ghoul girls” and coined the term “succubus chic.” Eyebrows were thinned, bleached, or removed entirely. Lips got darker. Skin turned matte. TikTokers posted tutorials on how to create dark circles and under-eye bags using makeup. Celebrities like Miley Cyrus and Chrissy Teigen removed their buccal fat to achieve a more “structured” (some would say “skeletal”) look. The bastions of the BBL body and body positivity began to shrink. Kim Kardashian appeared on the cover of Interview’s 2022 September issue with bleached blonde hair and eyebrows, standing in front of an American flag—looking thinner and whiter than ever before.

That same year, I was watching another music video when I realized the tectonic plates of beauty culture were shifting once again. In Snow Stripper’s “It’s a Dream,” the group’s hypnotic front woman Tatiana Schwaninger dances with guns—in front of yet another big American flag—looking effortlessly cool and astonishingly thin. It suddenly hit me: the waif was the new baddie. Girls in the 2000s had to trawl pro-anorexia blogs for tips on how to look like Paris Hilton, Mischa Barton, or the Olsen twins. The vast majority of them suffered tremendously and never reached their goals. Girls in the 2020s actually can look more like Schwaninger––all they need are drugs, needles and the right resources.

Still of Snow Stripper's Tatiana Schwaninger in "It's a Dream" (2022)

III.

Earlier this month, The New York Times ran the op-ed “Why Are We Doomed to Keep Reliving the ’90s?” The word choice felt pointed—particularly in the context of the Ozempic era’s obvious aesthetic predecessor: heroin chic. “You do not need to glamorize addiction to sell clothes,” President Bill Clinton said in a filmed speech, after the death of teenage photographer Davide Sorrenti. Though heroin chic was publicly denounced by the late ’90s, the images, music, collections, and designs associated with the gaunt, grungy look have been admired and recirculated online since the early days of the Tumblr era—particularly among communities that have an affinity for indie or alternative aesthetics.

But the aestheticization of illness in the ’90s has a much longer lineage. In the Victorian era, people dying of tuberculosis were believed to be among the population’s most beautiful. Writers and painters depicted the frail, sickly bodies of the fatally ill as aesthetic ideals. Women aspired to resemble those afflicted: they washed their skin with ammonia to appear pale, applied blush to mimic fever, and put belladonna on their eyelids to dilate their pupils and give their eyes a glassy look. Belladonna was a cosmetic made from the poisonous plant, atropa belladonna––the side effects of its usage ranged from blurred vision to permanent blindness. The link between the pursuit of beauty and the willingness to suffer has been present across almost all cultures and throughout time—be it in centuries of foot binding, corsetry, scarification, or lip plating.

For anyone with chronic illness, or anyone who is taking a GLP-1 out of medical urgency, the growing population of off-label injectors—who endure side effects completely voluntarily to reach a particular aesthetic or emotional goal—may be confounding. But is it really so different from longer-held invasive beauty practices that have become commonplace? There are now more places to get injectables (Botox, filler), laser treatments, and chemical peels near the 032c office on Kurfürstendamm than there are places to get a decent sandwich. Trendy treatments like microneedling also cause harm to the body in order to “fix it.” In the grand scheme of things, what each of us yearns to “fix” and the avenues we take to do so are far less important than identifying the larger forces at play that make us feel we need to be fixed.

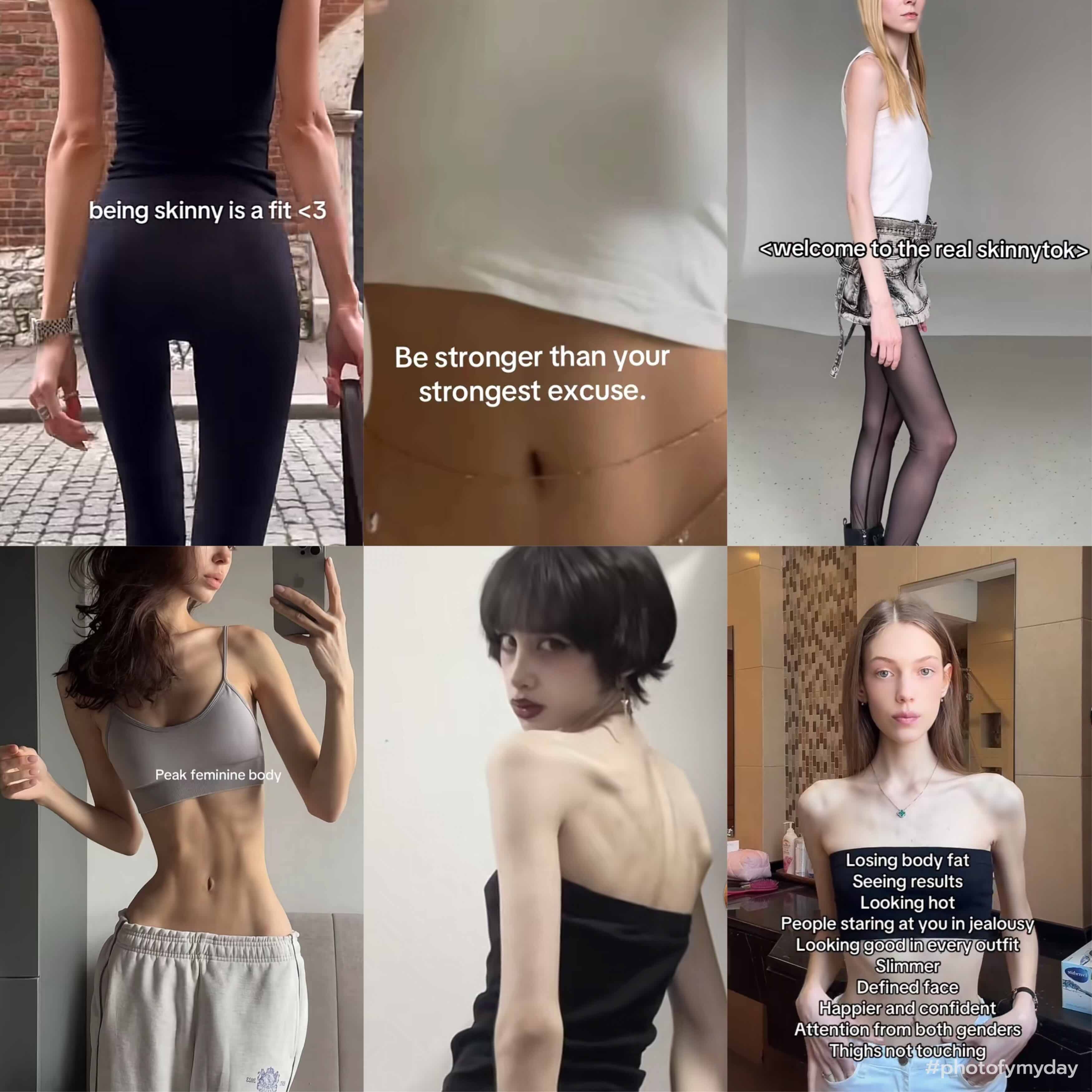

“You’re not alone,” TikTok now tells you when you search #Skinnytok. “If you or someone you know has questions about body image, food, or exercise—it’s important to know that help is out there,” it continues above a link to various aid “resources.” Although the hashtag was banned this year, similar content is still easy to find under near-identical tags. “Control yourself,” one audio track screams over a demonic beat. Girls match it with footage of themselves in larger bodies, followed by montages of raw vegetables, gym mirror selfies, and loose-fitting clothes. “You said change, so I did,” reads the caption in another video made by a teenage girl who proudly documents her weight loss.

Screenshots of #Skinni content on TikTok

The return of the thin imperative is just one of many political triumphs among those who propagate this doctrine. “How I Stay Silent, Skinny and Unbothered,” Liv Schmidt wrote in a post on The Skinni Société, her private Instagram group, which users can only access with an approved application and paid subscription. The thin, blonde influencer is the biggest name associated with the now-banned hashtag #SkinnyTok, where she once posted tips on how to be thin and lose weight. “Eat whatever you want, just eat as little as possible,” one caption read. Schmidt was deplatformed by TikTok for promoting disordered eating, but the ensuing media frenzy only increased her fame—and subscriptions to her community. She has since been embraced by far-right online spaces and praised by publications like Evie (the alt-right’s Elle) for being “honest.” If you consume Schmidt’s content or anything else “skinny”-related, algorithms will soon start feeding you other conservative-adjacent content, such as videos of #Tradwife Nara Smith cooking elaborate meals for her husband while narrating her domestic activities in her signature whisper.

In extreme right-wing ideologies—which position themselves in direct opposition to the values of body positivity—thinness is not just aspirational. It becomes a moral mandate, much like heterosexuality. This logic has roots in fascism, which upheld traditional gender roles and family structures in the name of purity, uniformity, and state reproduction. In his 2002 book Body Fascism: Salvation in the Technology of Physical Fitness, Brian Pronger coined a more specific term for this phenomenon in the internet age. He defines “body fascism” as a digitally driven, nihilistic belief system that rejects the “weak” and posits the idea of physical perfection as a means of transcendence. Oxford’s Dictionary of Gender Studies similarly defines “body fascism” as weight-or-appearance-based discrimination—mostly targeted at women—that aims to keep them slim, obedient, and “attractive” within the prevailing heteronormative confines.

Whether it’s manifesting as mewing, mogging, or #looksmaxxing in the manosphere, or as Schmidt’s infamous “three-bite rule” in her corner of the internet, right-wing beauty discourse is contingent on the re-establishment of hierarchies and the idea that looking a certain way makes one superior to others. This same logic has been used to uphold fatphobia and transphobia, but also racism and white supremacy. The idea here is simple: men should amass privileges and power by building muscle and attaining a certain physique, while women should take up as little space as possible—by shrinking themselves, eating less, and (quite literally) keeping their mouths shut.

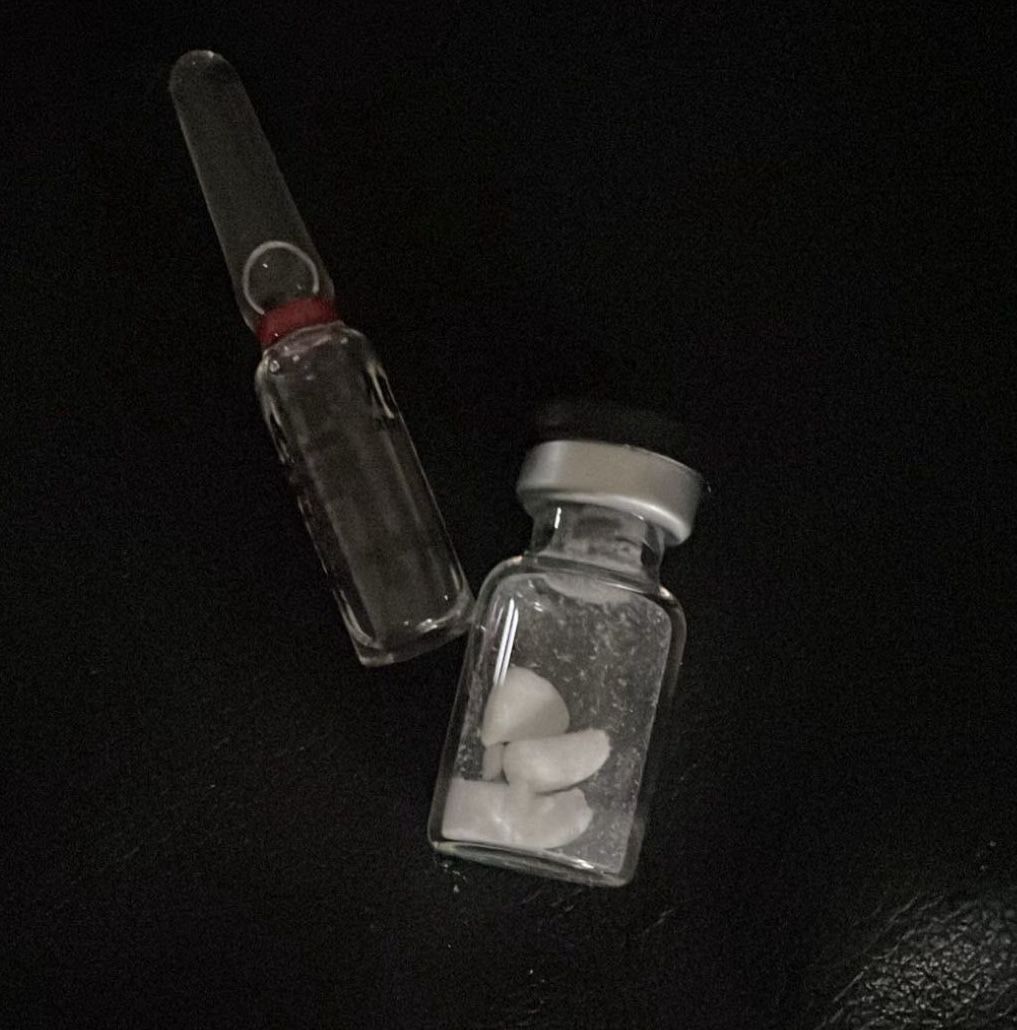

Semaglutide that was purchased from China via a Telegram group

IV.

Last month, I received an invitation to a social event where more women on the guest list were taking semaglutide than not. “Everyone is on it,” one of them told me. “It’s just that nobody is talking about it.” Eager to hear more perspectives––ideally also from people I don’t know––I put out an open call on Instagram. Under the condition of anonymity, numerous people shared their stories.

Anonymous 1

The process [of getting a GLP-1] was scarily easy in the US. All you have to do is use a random telehealth website and complete a five-minute survey. I lied and said my BMI was 10 points higher to qualify.

Every once in a while, I get painful trapped gas or a sudden fit of vomiting. When I feel sick, I think: “Cool, I’m doing this to myself. And for what?” But then I think, “A few days of feeling sick versus the discomfort of daily dieting, calorie counting, and hunger?”

With Ozempic, it’s more or less accessible to be skinny now—it’s sort of like a calling card. I once read a theory that said the BBL body—once aspirational—became too affordable. Now it’s associated with more street-level culture, which makes it less desirable to celebs [and everyone else as a consequence].

It’s crazy to realize I’m willing to inject myself and take extreme measures. It forces me to face how much I value appearance. Right now, I’m crying in a hotel room eating plain rice. It’s very pathetic.

I do wonder how differently people would think about Ozempic if you had to inject it into a vein.

Anonymous 2

Honestly? I love it. I really love it. I eat way healthier now, mostly because I don’t have any cravings anymore. My confidence is at an all-time high. I also go to the doctor regularly for checkups, especially because I know it can be risky. But I make sure to eat enough. I’ve been really lucky—I haven’t had any side effects at all, except that hangovers last a bit longer. Other than that, I feel amazing.

I’ve only told my closest friends—maybe four people know. I get the sense that people don’t talk about it because it feels uncomfortable, or because it seems “too easy.” But honestly, it’s not that easy—you still have to work out and eat properly. Otherwise, you just end up looking skinny-fat. I do feel like things are heading back in a less healthy direction, but I don’t think anyone should feel pressured to follow a trend. That said, if there’s a way to feel better in your own body, I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that.

But I would never recommend Ozempic to anyone because I think taking drugs is a personal decision. Speed is a good comparison. If I was in a club and someone was super tired but wanted to stay awake, I would never recommend that they take speed—or any other drug.

Anonymous 3

This medication is only available by prescription for people with a BMI of 30 or higher, and my starting weight was 110 kg. My doctor recommended and prescribed the medication, and it’s now effectively helping me reach my goal weight.

Going out to eat with friends is no longer fun because you’re always being watched, and people comment on how much you’re eating. The feeling of fullness sets in after just a few bites, and you end up sitting at the table with a full plate while everyone else shovels their normal portions in. The consequence is social withdrawal—you start avoiding meals out or parties because you don’t want the scrutiny.

I’ve noticed a lot of public bashing of women who’ve lost weight lately online, and in most cases, it’s assumed they only achieved it with the help of Ozempic. Then I think: “How dare you criticize the tools that help me?” I never wanted to discuss it because of all the stigma and shaming I was seeing online. Everyone’s story is different, and no one knows what others go through. But if you’re “cheating” with Ozempic, then apparently, you don’t deserve applause.

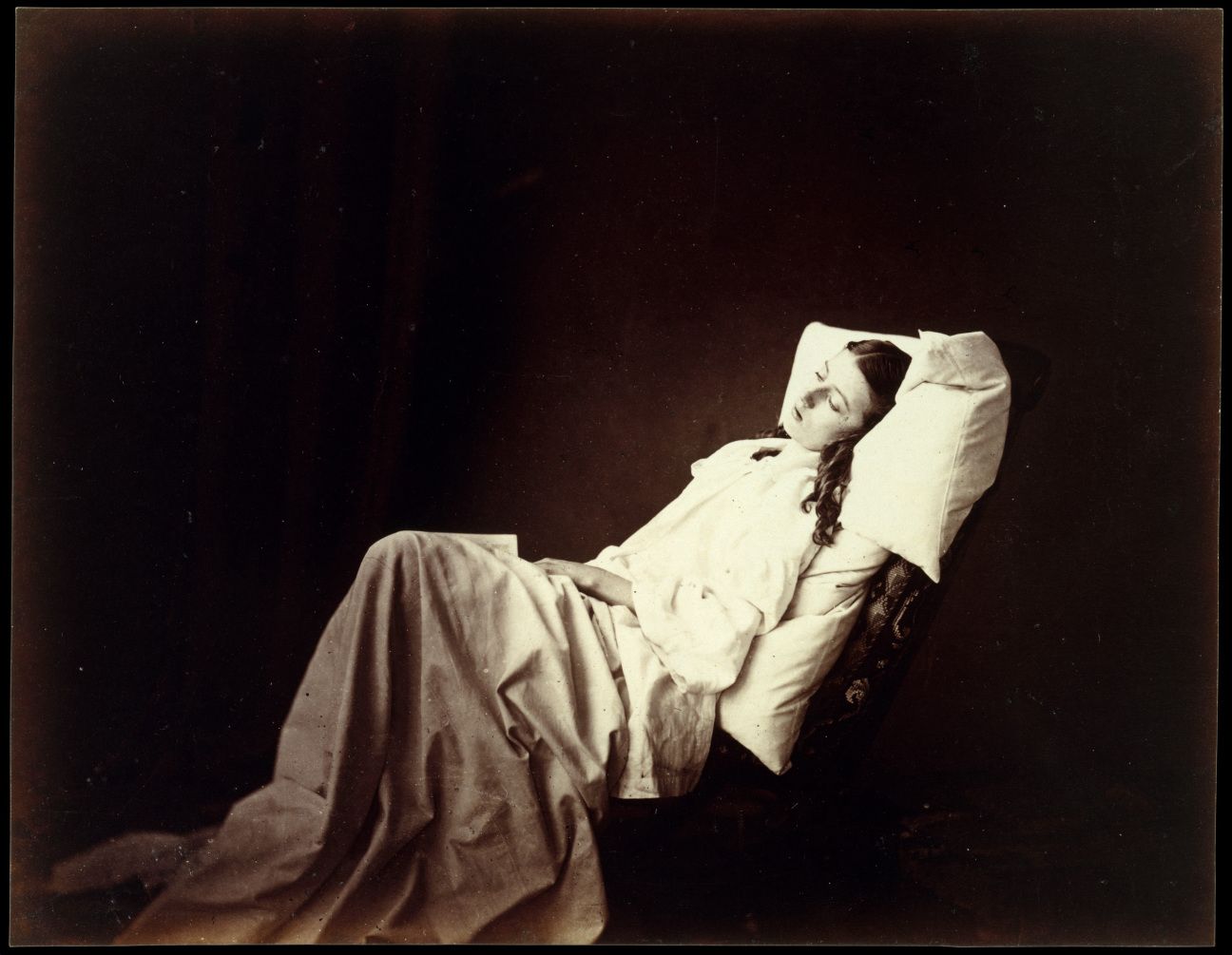

Henry Peach Robinson, She Never Told Her Love, 1857

Anonymous 4

I went on Mounjaro in August 2022 and never stopped. I love it. I got all my friends on it too! Lol. I started because I would diet and never lose weight. My doctor prescribed it when it first came out, but I also support using it for vanity or aesthetics.

It makes me not hungry and not obsessed with food. I can fast easily. The side effects are constipation and fatigue, but I don’t think it’s as extreme as some people think. I know a lot of models who take it regularly. It’s just a tool. You can abuse any drug. Just because some people abuse it doesn’t mean it can’t be used safely.

My personal beauty standard is specific, but I don’t project it onto others. I like being very thin now, but I also think it was cute when I was fat. I feel like transition/detransition, blonde/brunette, fat/thin are all just choices. I like being everything.

Anonymous 5

I’ve tried Ozempic, Wegovy, and Trulicity. Then I started buying semaglutide itself, and it was the easiest of all. It’s honestly been life-changing. I lost 25 kg in 10 months and had a glow-up—physically and mentally. My skin got better, my eating habits improved, and my body feels fitter. For me, losing weight wasn’t just about aesthetics. I had liver issues, and now my test results are much better.

I first got it for €60 a pen, but now I buy it online from China through a Telegram group. You can get it from the same guys who sell Viagra or testosterone. I only pay €30 a month.

So many people who promoted body positivity when they were bigger jumped on the Ozempic train the second they could. Me included! Skinny was always attractive—it’s just easier to reach now. Society treats fat people like they’re weak and lazy. But as soon as people hear you had help getting to the version of yourself that society prefers, it suddenly doesn’t count.

Anonymous 6

I’m at a weight I’ve never reached before—and at a size I always wished to be. I could never achieve it through diet and exercise alone, and I’m so grateful. Other people deserve the same happiness. But of course, it’s two-sided.

Now I only take it to maintain my weight, because if I stop, I gain weight again immediately. I’ve also started getting more serious side effects. When I was on Ozempic, I had bad stomach pains and felt sick often, especially when I was moving a lot or drinking. Last week, I took a dose of Mounjaro after taking a break for a few weeks and had to spend three days in bed because I was so tired and nauseous. It felt like food poisoning. I realized it’s starting to negatively impact my life—not just personally, but professionally. I wasn’t able to work those days—I was just suffering.

I know so many people taking Ozempic, I feel like everyone is on it. All my friends who are taking it looked amazing even before—they weren’t overweight. Now they’re sooo skinny. When you see that in your environment, you feel like you have to be the same—even though you don’t. I haven’t even reached my goal yet, which is four kilos less, but I don’t even know how to get there.

Milla Jovich photographed by Davide Sorrenti, ArgueSKE 1994-1997 (2020)

V.

It only took me two hours and a few text messages to get in touch with someone selling Ozempic in Berlin without a prescription. When you message the owner of this small salon, you receive an automatic WhatsApp reply in German and Turkish:

Wir melden uns in Kürze bei Ihnen 🌸 Size nasıl yardımcı olabiliriz?

(“We’ll get back to you shortly 🌸 How can we help you?”)

A small bell rings when you enter. A beautiful, friendly woman greets you at the door, while customers get their eyebrows threaded in the background. For €250, you can purchase an Ozempic pen she keeps in a mini-fridge in the back, which contains four to six weeks of doses. If you choose to buy one, she will quickly explain how to dose Ozempic before sending you out the door with the pen in a plastic to-go bag, which is covered in red Christmas bows.

The black market for GLP-1s is thriving. Many off-label injectables are purchased from China, where pens are fifteen times cheaper than they are in America. People who can’t access GLP-1s are turning to “budget Ozempic”—a trendy term for laxative use, which has contributed to a Miralax shortage in the States.

The meteoric rise and off-label use of GLP-1s has disturbing parallels to the opioid crisis, and the new aesthetic ideal clearly echoes heroin chic. However, it’s far harder to assign blame to any particular entity than it was in the past. In the 2010s, discourse around body image revolved around the toxic influence of traditional media. But now, with the redistribution of power and influence on platforms like TikTok and Instagram, we are also the media. Anyone who posts a photo or video of themselves online becomes a node in the system. Before digital photography—and before every phone had a camera—only models, celebrities, and public figures were routinely photographed. On social media today, we constantly surveil ourselves. We can’t point fingers at Big Pharma or fashion any more than we can at each other.

With so much incentive to be seen—and so much awareness of how others appear—is it any wonder the pressure to conform has never felt more intense? And with so many tangible privileges to be gleaned, is it any wonder that people are willing to take extreme measures, or use whatever tools are available, to get there?

The supremacy of skinny is, of course, most dangerous for our most vulnerable, which includes young people and those with disordered eating. For the latter, the impact of the ubiquity of GLP-1s is so far inconclusive. They have been described as “helpful tools” for those battling binge eating or bulimia due to their ability to reduce “food noise” and obsessive thinking. Other doctors have reported an alarming rise in drug-induced anorexia and called GLP-1s “rocket fuel” for those with eating disorders.

Radiofrequency microneedling aftercare

The cruelty of contemporary body politics is not only visible in fatphobia and body shaming, but also in the judging and shaming of those who choose to take GLP-1s. The notion that taking Ozempic or similar drugs is a “cheat code” reinforces the idea that people who do not or cannot conform to certain ideals without them are simply lazy or incompetent. With Roe v. Wade overturned in the U.S., it’s already clear that the slogan “my body, my choice” no longer holds weight in the current zeitgeist. But in an age of viral influence, oversharing, and diminishing capacity for individual thought, what people choose to do with their bodies—and the methods they use—has consequences for others, particularly if they are vocal about it. Herd mentality is human nature, and when thinness brings with it the reward of beauty and belonging, the temptation to chase it becomes harder to resist.

If you haven’t at some point in the past few years considered—or at least felt curious about—drugs like Ozempic, congratulations: you’re one of the lucky ones. As pressure mounts to shrink, “improve,” or “get in line,” the choice to love, accept, or nurture the body in its natural state feels increasingly radical—and increasingly necessary. Although it is playing out in public theater, this battle with “beauty” should be an individual one. How far will you go, how much will you spend, and what are you willing to sacrifice in order to look how you want?

What we know is that—among the increasingly large population for whom taking GLP-1s is optional rather than mandatory—the emotional burden of the weight they seek to lose is so great that they are willing to make a substantial financial commitment and become physically dependent on drugs, potentially for the rest of their lives. This reality says less about the psyche of these individuals than it does about the state of the world.

When I attended the Ozempic-majority social event, I felt grateful that I was able to eat more than a few stalks of asparagus without feeling ill, like some of the other guests. But a few weeks later, I found myself staring at the ceiling of a practitioner of “aesthetic medicine,” basking in my own hypocrisy. I was there for a radiofrequency microneedling session with a controversial machine, which has needles that penetrate deep enough to melt fat in the dermis. “This will hurt,” the doctor warned me, before she began attacking my cheeks with the handheld device, which is shaped like a gun. As my face started to bleed and my eyes began to water, I could only muster back two words: “I know.”

Credits

- Text: Cassidy George