RED ROSES FOR AYSCHE: Twilight in Kreuzberg with Artist MATTHIAS STEINKRAUS

|Eva Kelley

It’s a warm evening in Berlin and the sky has just dipped itself into a dusty pink. I’m in the rooftop cafeteria of the Karstadt Center, a heritage department store that was one of the largest department stores in the world when this branch opened in 1929, and which now occupies a large gray mass of a building archetypical of post-war 1950s rebuilds. Behind me, the cafeteria is serving potato croquettes and raw herring salad; before me, beyond a sea of flimsy aluminum tables and chairs, is a panorama of Kreuzberg and Neukoelln – two of Berlin’s neighborhoods that typify the more recent phenomenon of displacement, notably of the area’s historically immigrant and working class communities.

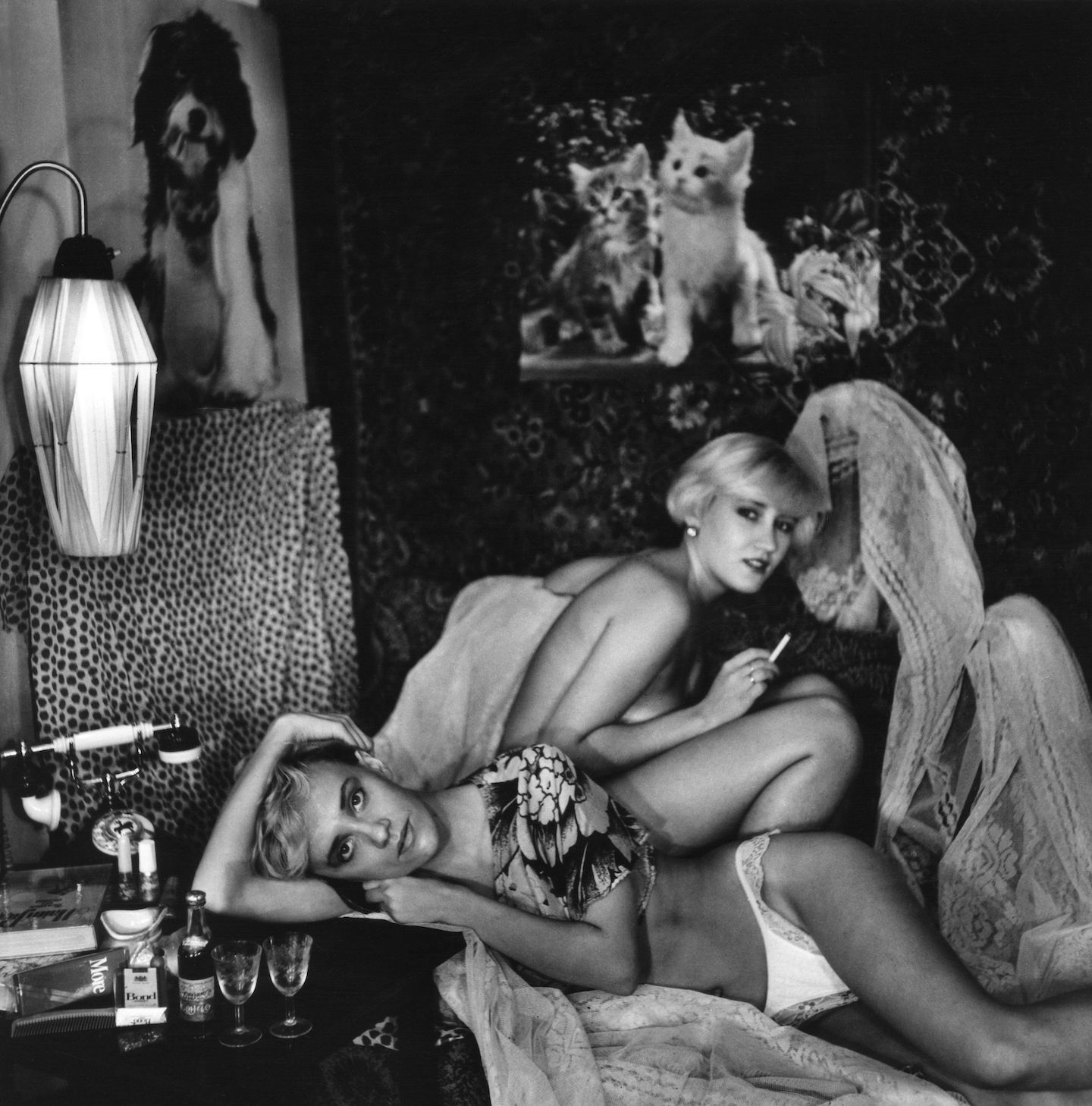

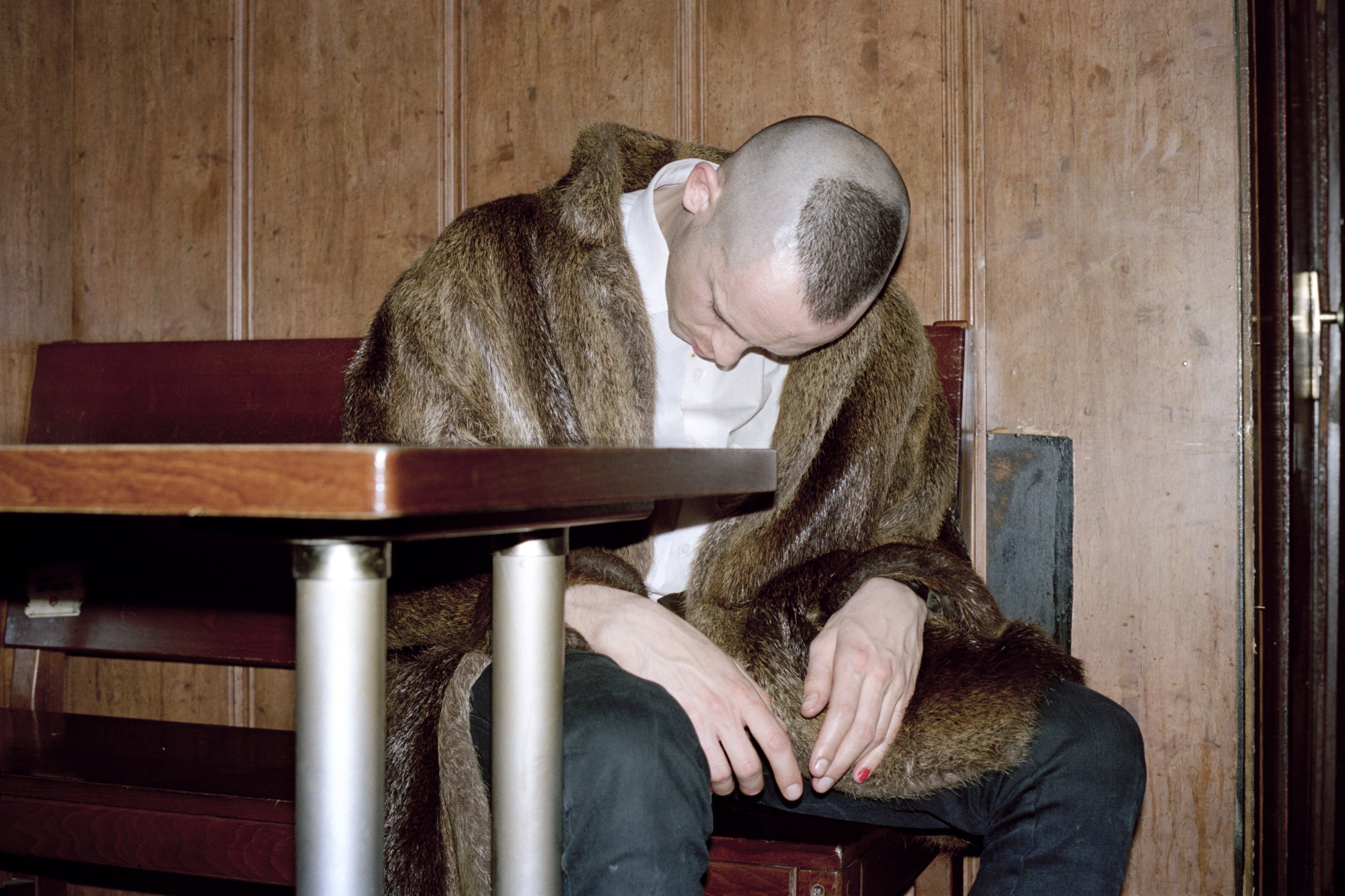

I am waiting for Matthias Steinkraus, the 30-something German artist whose debut photo book, Rote Rose (Hatje Cantz, 2018), chronicles the regular visitors and everyday goings-on at the infamous 24-hour pub on Adalbertstraße for which the publication is named. Steinkraus’s lens is drawn to life in the margins of a post-reunification cultural center: to the dive bar, the back alley, and the kiosk, and to the social housing built when Kreuzberg was one of the poorest and most isolated areas of West Berlin, before the hype.

I have no idea what Steinkraus looks like – I have only been able to find one, purposefully blurry portrait online. When I ask him later if I can take a picture, he calmly responds: “You can take one for your private use, in memory of this evening.” As I would shortly discover, Steinkraus leaves very little to chance or to impulse: after the artist found himself becoming a Rote Rose regular, he began to consider every detail of its architecture, its clientele, its surroundings, and the contexts and realities that brought these elements together. It took him six years to finish Rote Rose.

But now, when I hear the soothing whoosh of the sliding glass doors open up to the terrace behind me, I turn in eager anticipation to prove the likeness that has formed of him in my mind. “Eva?” he asks.

Eva Kelley: You are nowhere to be found online.

Matthias Steinkraus: I want to disappear behind my work.

You don’t even have an Instagram account.

I have a spy account.

How did you end up spending so much time in the bar Rote Rose [“Red Rose”]?

When I finished my fine art studies, I noticed quite quickly that I wasn’t moving forward with painting. I had nothing to add to it. That was difficult, to try at something and fail at it. And then I had a crisis. To get over this trauma, I went out a lot and stumbled into this culture of Berliner old corner pubs: the classic “Bierstube.” I felt at home immediately. The alcohol helped of course, but the clientele is just incredibly nice and open. You’re immediately involved in a conversation.

I can see that. When you’re in a crisis, it’s calming to be in an environment in which people aren’t so consumed with impressing each other.

Your status doesn’t mean anything there. It’s sad as well, because there are broken existences behind it. In an inebriated state, it’s a safe space where you can practice escapism: the nice side of life. It represented a new world to me, something unfamiliar. My dream of being an artist in Berlin had been shattered. I came to terms with it in that bar.

Were you alone or with friends when you went to Rote Rose at night?

I was there alone often. I did a lot of Kotti-controls; checking up on the Kottbusser Tor area.

Picture someone far away who has never been to Rote Rose in Berlin. If you would transport yourself into the bar, could you describe who you see, what it smells like, and what kind of music you hear?

You would hear rock classics. They have a jukebox, ten songs for two Euros. It’s a very good music selection, actually: Pink Floyd, Tupac, Madonna, Rammstein, The Who. The first time I was there, Depeche Mode’s “Everything Counts” was played ten times in one evening, at least. It’s very smoky. The toilets smell really horrible. Everything else is so beautiful though that you kind of forget about the smell. People talk about the past. And sometimes about pets. There is one guy who works at Deutsche Bahn. There is this old intellectual guy with glasses. Then there is a drug dealer who is always there. Aysche is there. There are groups of young people who are there because it’s become a cult bar.

What do the people in the photographs think of the book?

It’s always difficult with portraits. In that context – at night, with alcohol – a portrait easily becomes a sensationalist image boasting with proof of a certain milieu.

Do they know the book exists?

Two people that I know of do. The images were all taken with the consent of the subjects. I proposed doing the launch in the bar itself, but I decided against it because I think it would have been disturbing for the patrons. It’s very important to me that nothing hurts the people in the pictures. I was a part of that place for a while, and I think that Berlin would lose a part of itself if these people disappeared. You can live in bars. These people practice a different identity search. It’s not just a safe space for the old Berlin milieu but also for an alternative lifestyle. They are a part of the life quality in Berlin.

You were a part of that bar scene, but at the same time, you’re also very clearly an outside observer. Now you’ve extracted yourself from this milieu and are profiting from the experience. Is this difficult for you, emotionally?

It honestly feels like I pressed “pause.” Once I realized that I needed a certain kind of professionalism to realize the work, I understood that I could only achieve this by implementing a theoretical approach and taking the political and societal aspects into account. It became less about how to make the photos and more about how to handle them. I was still going out, but less and less. When you do it right, it takes up a lot of time and energy. And alcohol. It’s fun as well of course.

How did the series come into being?

The first year or so, I took pictures in the moment. I didn’t plan to make a series out of it. I just always had a camera on hand for the memories. At a certain point I noticed that there was actually good material in there. After that, I went to the bar with intent. I started teaching myself about the history of photography and the technical aspects. I also always felt like it was a time/space capsule, a place where the old Kreuzberg is still visible. These wood-paneled bars have survived times that are long gone, just like the people in them.

How does your training as a painter inform your work as a photographer?

I never found photography very exciting because the discourse is more focused on the motif of the photograph rather than the material. Painting is the opposite: it’s not about what you see, but about how it’s made. While I was learning about photography, I realized that I was participating in social documentary. The classical social documentary style doesn’t work for me, because the genre-typical motifs are so over-used – everything has a homogenous look. The genre easily creates caricatures. It usually gives the viewer exactly what they expect. I wanted to show the displacement that I was documenting visually on a material content level as well. I started using all different kinds of cameras. I used these tiny phone cameras as well as hi def cameras. The essential characteristic of the book is also the formal structure, actually. I set a certain height and width for the images, and because they come from different cameras that produce different resolutions, they jump around in quality. This mirrors my perception of truth. In one hundred years it won’t be possible to work like this, and thirty years ago, it wasn’t either. So it’s kind of like a social and technological echo chamber.

How does the architecture around the bar come into play?

The situations in the bar are quite beautiful, but there is a roughness that accompanies that beauty, which is visible in the architecture around the bar. I realized that when you photograph these people, the milieu is automatically tied to them. It immediately has a socio-political context – you can’t free one from the other. There is a gentrification, standardization, and development happening that has lead to a displacement of the neighborhood.

Like the New Kreuzberg Center (NKZ) – the late 1960s social housing project that is portrayed a lot in the book.

The NKZ represents a city utopia gone wrong. It was built to increase the life quality of the residents and build a community. At the time, Oranienstraße in Kreuzberg was supposed to be demolished to make way for a highway, and in preparation for that, they sound-proofed the NKZ. There was so much resistance that in the end, the highway wasn’t built. The soundproofing wasn’t even necessary. The building was a utopia all by itself by the time it was completed. It’s strange that the area around Kottbusser Tor has become more uncomfortable with its quirkiness, more anxious and tense against the backdrop of the gentrifying developments around it in Kreuzberg.

Will you be going back to the bar?

I don’t think I will be taking more pictures in the bar. The Rote Rose itself shouldn’t be given too much importance. It’s a typical example of a Berliner corner pub – I just liked this one the best. The NKZ as well is exemplary of something that also exists in other countries. I situated it in Berlin, but it’s also about displacement in inner cities everywhere. This is a state that occurred in Paris and Rome years ago; it’s happening now in Manchester, Liverpool, and Lisbon. So, the work is about Berlin, but it also surpasses its boundaries. If you only see the gentrification theme in the book, then you’ve missed out on an essential part: The marker of the book is the form and the way it is made and created, how it has been put together.

It’s interesting that you felt so at home in this specific bar, at this specific site of tension, though. The emotions and the atmosphere inside are so severe. It has always given me this chilling feeling that no one there has anything left to lose.

I think it finds its equivalent in architecture in the NKZ. It’s a graphic building: very hard, with angular edges. This mood is mirrored in the building. I’ve absolutely experienced what you’re saying. Because I was there so often, I probably saw the entire spectrum. The consensus with my friends has always been, you know, “Rose – you have to be in the right mood for that.” It can be too much. I wanted the viewer to be transported to a certain place, to a night in that Kreuzberg, where a new story is created every night.

It’s also always the same story.

The same. Same, but different.

Rote Rose by Matthias Steinkraus is published by Hatje Cantz (Berlin, 2018). All images: courtesy Matthias Steinkraus

Credits

- Interview: Eva Kelley

- Photography: Matthias Steinkraus