Prada Undone: Inside Artist CHRISTOPHE CHEMIN’s Revolutionary Reference System

Writer, filmmaker and visual artist Christophe Chemin’s prints for Miuccia Prada’s new collection were the talk of the town at Milan fashion week. For a new show at 032c Workshop, the Berlin-based renaissance Frenchman explores the books, films and images that went into his work.

Even by the standards of onetime Communist Party card-carrier Miuccia, Prada’s FW 2016 collection was unusually politically charged. Taking as its source texts “immigration, famine, assassination, pessimism”, at the centre is a series of prints by one of Berlin’s most fascinating and multifaceted ex-pat artists: Christophe Chemin, a man known for his enfant terrible experimental novels, photobooks on the wretched beauty of the Virgin Mary, underground art films and exhibitions of exquisitely disturbing drawings.

For the FW 2016 collection, the self-taught artist drew a series of mythic images from classical sources and the 20th century, depicting Jeanne d’Arc, Che Guevara, Nina Simone, Hercules and more locked in embraces, half ballet and half brawl. In one, white mice feast on a 17th-century banquet table straight out of a Louvre still-life. In another, Cleopatra is locked in a kiss with James Dean. It’s a modern fever dream, the sort Freud (pictured below, wielding a cudgel) would have had a field day with.

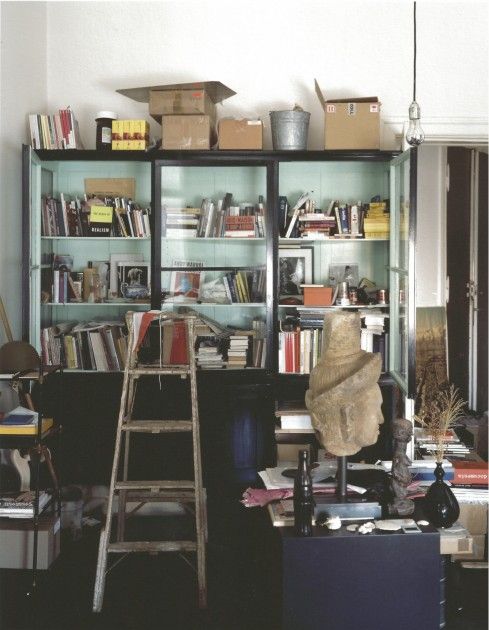

For his show at 032c’s Worksop exhibition space, Chemin has turned the St Agnes vitrine into an exploded diagram of his creative landscape, unpicking and displaying the materials that made up the work. Taking in Baudelaire, an “Elvis” brand soap from the DDR, white denim jackets, the French Revolutionary calendar, Pasolini and Czech liquid modernist texts, it’s a mappa mundi of the objects, images and ideas that made the collaboration such a capital-M moment in the evolving conversation between fashion and fine art.

Swing by the space if and when you’re in Berlin: it’s on show now until 25 April, and if you’re swift, you can buy a limited-edition exhibition poster by clicking here. Otherwise, read on to find out more about this incredible artist, and why he believes it significant that art is an anagram of “rat”.

Could you tell me about the exhibition title “keep your daisies for the cold days”? Where does it come from and how does it relate to the works?Christophe Chemin: First of all, as a writer, I like the way it sounds. There is a clear confrontation of sweetness and irony in that sentence, a real tension – and I am someone who likes tension. Tensed, as in ready and alert. You can read the oxymoron of the title in many different ways or levels. The front door is wide. It doesn’t have one source, but part of it is a subtle reference to Pier Paolo Pasolini. At the end of Salò, there is this incredibly violent scene, the film’s last shot. Two young soldiers, who witnessed and collaborated in all the atrocities perpetuated during the film, are dancing a simple waltz together, in the middle of a room full of Bauhaus elements and cubist paintings. One boy asks, “What’s your girlfriend’s name?” The other one answers: “Marguerita.” It sounds banal, but the last word pronounced in Salò is the name of a very simple flower: a daisy. Keeping your innocent little flowers for the cold hard times suggests, “Be prepared… Everything is not what it used to be, or what it seemed to be.” And as the croupier announces in the Roulette game: Rien ne va plus! – a French sentence I love. This bittersweet daisy chain investigation is the thread of the work exhibited. A certain type of romanticism undermined by social criticism. Things are happening in between the lines, defying categories or judgments of tastes and aesthetics. There is, in the work being shown, a preoccupation with the actual situation we are in, but the approach is not direct – it would be too vulgar. An image can hide—or nest in—another image, like Russian dolls. You will not only find images in the exhibition, but texts, words and numbers – like codes and landmarks. Lots of flowers from all kinds tied one to another, because flowers are always misleading people. And on a lighter note, the title can be red as a sartorial reference: If you have flowery clothes, wear them when it’s freezing. Or, as a precious and personal warning addressed to a child.

The labels displayed are details from the works, but how do other, smaller details on display in the vitrine relate? Which role do they play?

The many labels pinned on the wall next to each artwork are the actuals ones we designed for the clothes at Prada. Each artwork has its own collection of labels: a jacquard detail of the work, its title, and a series of little tags with years. These precise years work as key elements, and what they refer to is not a mystery: It is displayed into the vitrine in a sort of archeological style. If you really take the time to look into the elements, you will suddenly start to see what connects them all. It is like digging into the earth. An Elvis soap from the DDR, an old key, pens and knifes, human and animal bones, match boxes and postcards. They are relatively “useless” objects. Nowadays, we don’t really use keys anymore, we use combinations of numbers that we know by heart. Those are the new keys. Personal identification numbers and passwords, WhatsApp, and emails. The artwork on the walls is attached by pins or by nails, and at each extremity of the vitrine you will find two opened books. The whole vitrine and the way it is installed could be an interval in time, from one book to another. The book on the left side is Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal, the one on the right side, closing the vitrine, is Patrik Ouředník‘s Europeana: A Brief History of the Twentieth Century. And there is one clothing element, a shearling white denim jacket I did for the show, hanging in the vitrine. It is not a self-portrait, but a way of re-appropriating for myself the notion of things to wear and connecting it to the concepts of safety and protection—a recurring concern in my work.

Can you describe your concept for the arrangement of the works in the vitrine? How did your collaboration with Prada affect that?

I absolutely love the vitrine in itself, the glass, the sliding doors. It is a beautiful object that offered me many possibilities to display the work that was already done. I find the proportions really unusual. It gives this feeling to the viewer of standing, like in supermarkets, in front of an elongated box, almost like one deep, oversized frame. The concept is very straightforward: I consider the different elements closed inside being one piece of work made in situ, and its title is keep your daisies for the cold days. There is a sort of Prada infection happening inside this box, consisting of pins, labels, needles pressed in the walls as well as invitations to the fashion shows. But as it is not a Prada exhibition in any way, I replaced their usual labels with some little ones made to my own name – a sort of contamination game I took a lot of pleasure to play with. I love this idea of things contaminating each other. You know, “art” is an anagram of “rat.” There are originals I did for the brand next to revisited versions, totally new work, and even reproductions of old artwork of mine that originated some of the images I ended up proposing to Mrs. Prada, like the window collages. Finally, there are six new text pieces, visual narrations, or evocations of images to come. They reveal our creative process. I call them Prada undone, which is ironic. But I think they complement very well the rest, as they are a very good example of new individual work generated by some of the collaboration left overs. It is a good way to confuse people, in my opinion.

How does 1980s imagery of Berlin relate to this world and the collection? Are you a fan of Christiane F.?

You are referring to a collage called Nivôse I did for the womenswear. Nivôse, in the French revolutionary calendar, is the month of December, and I got this idea of doing a metaphor of the city as a woman. The city at night, lying under a white coat, shining in her colorful neon lights and trees made out of pearls, full of candles. The metropolis herself, where anything is possible: a world of unknown mysteries and pleasures glowing in the dark. The infamous subculture of Berlin’s nightlife from the 1920s and from the 80s, with its cinemas, radios, experimental music, and underground clubs being the main reference—Zoo, SOUND, Vox, Babylon, Nico. A dangerous urban labyrinth of freedom that still exists. What I like about Christiane F. is this plastic bag she is constantly carrying on herself everywhere she goes. I am a big fan of Werner Herzog’s Stroszek, and that film is the reason why I first moved to Berlin.

Do you feel there were certain aspects of the work you could highlight through the exhibition that might not have been as apparent, or more in the background, in the collaboration with Prada?

I’m happy the exhibition happened so quickly after the two Milan shows – and here in Berlin. It is showing quite clearly, and in a very coherent way, the original material—but not in a fashion context, which in my opinion was important. Some parts you could not easily see on the clothes, for technical reasons. Some parts also were cut out, etc. It is a new invitation to look from close at what has been done and used. You can see that some of the work, especially the collages, is three-dimensional. You can see what is printed or not. The vitrine is also a place where people have more time and quiet to question what exactly they are looking at, I hope. Some of the visuals have so many details, it is hard to read them on clothes. You just get the aesthetic part of them, the outer shell. For example, the background of Impossible true love is the replica of a wonderful miniature I have been obsessed with for years, Morte del Sole, della Luna, e caduta della Stelle painted in 1476 by Critoforo de Predis, who was born deaf and dumb. It depicts the end of the world. The delicate color pencil drawing is in fact close to a collage. Which brings us back to the daisy chain system I mentioned when we spoke about the sentence keep your daisies for the cold days. The work exhibited that way, with the vitrine creating a unity, can start to reveal itself as an articulated ensemble. And I hope people will be curious enough to come see the work in person.

Christophe Chemin for Prada: keep your daisies for the cold days is on show at 032c Workshop, St Agnes, Alexandrinenstr. 118-121 until 25 April.