In the Philippines Content Moderators Cleanse the Sins of the Digital World

|Sven Fortmann

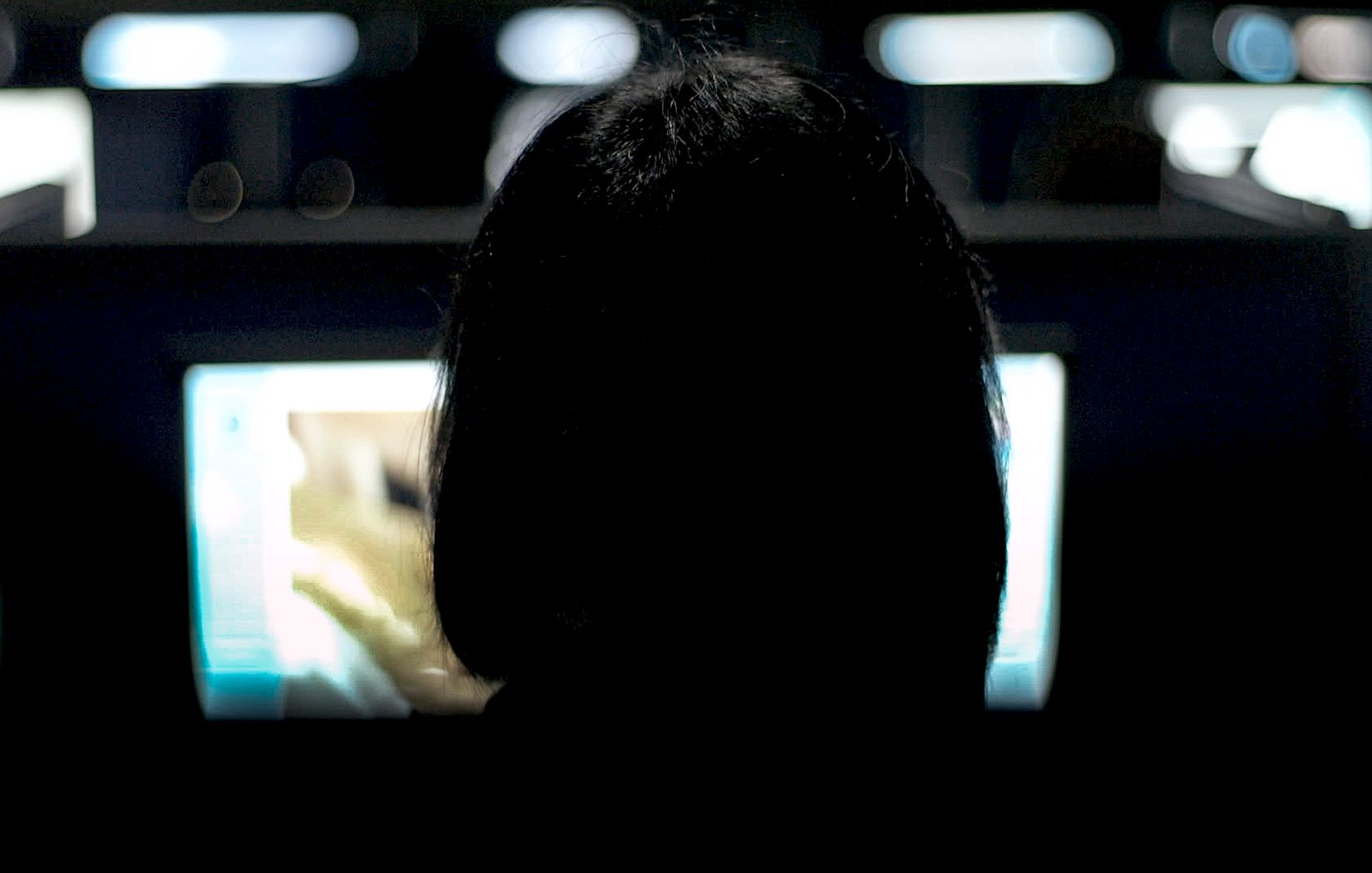

In The Cleaners (2018), German filmmakers Hans Block and Moritz Riesewieck reveal a shadow industry of content moderators – individuals paid to sift through the billions of gigabytes of content uploaded to social media each year. The work requires extreme psychological defenses, and is regularly outsourced by contractors to countries outside the US where employees are selected for a worldview that reflects a unique blend of Catholic and capitalist fervor. The interview below is excerpted from Lemonade, a summer special from the team behind Berlin’s Lodown magazine. Here, Sven Fortmann talks to Block and Riesewieck about the American decision-makers who regulate what content must be censored, the “parallel truths” of Facebook, and the conditions in the digital sweatshops of Manila.

I was surprised that The Cleaners saw its world premiere at the Sundance Film Festival earlier this year and not within the context of the Berlinale . . . what triggered that decision?

Hans Block: Well, both festivals belong to an exclusive circle of so-called A-festivals . . . and it’s rather rare that a film makes it into both festivals because they follow each other very closely and there’s a lot of politics happening backstage. The Cleaners is an international co-production, and it became rather evident that a few parties involved would love to see the world premiere at Sundance.

Moritz Riesewieck: For us, as German directors, it was rather absorbing to premiere the film in the US because in the film we predominantly deal with American companies and their parturition. The resulting discussions were really exciting ones, particularly since freedom of speech is handled as something very implicit over there. There’s this part where we portray this alt-right street activist – over here we’d probably would use the term “agitator” – and for the audience at the premiere it was rather natural to make his voice heard even though it was evident that this person would go on a rant against minorities in an instant. We immediately realized that the idea of a global network where each and every person is able to get their ideas across – which almost feels a bit naive as soon as Zuckerberg issues statements like that – meets very different problems of comprehension in Germany than it does in the States. I guess, mainly because of our pop cultural upbringing, you just cannot help but feel somehow connected to the US, but in reality there is a major gap between our countries in terms of morals and a general value system.

This drill starts during their elementary school days, don’t you think? There’s speech and debate clubs, talent shows, spelling bees. For most Americans it’s a matter of course to speak their mind in public . . . that’s something which still feels kinda alien to the majority of Germans.

HB: Right. Obviously there’s a different and rather significant historical context . . . in terms of violence, agitation and hate speech, Germans are extremely sensitized. We have a much more specific view of freedom of speech.

MR: It’s also highly interesting what is actually allowed to pass as “opinion” these days. I mean, these platforms, they try their very best for you to permanently speak up and be opinionated – that’s the very basic structure of how this site is built: what’s on your mind? Always express yourself, always speak up, regardless of how informed you actually are, regardless if you checked the facts or not . . . who gives a fuck, the only things that really matter are having an opinion and making it immediately known. In this way, the line between facts and information and reportage and opinion gets blurry, it becomes almost obsolete . . . and we believe that’s a pretty dangerous development. It’s not about the joy of being able to share anymore, it’s about having set up a platform where a statement or snippet can cause a major crisis.

HB: If particular snippets or “opinions” receive major attention through clicks and shares and likes, they become their very own truth . . . and this actually gets promoted through the architecture of the platform. The more extreme and shortened and sensation-seeking your post, the more clicks and likes you’ll most likely get, which then gets rewarded with advertising funds. This results in some weird parallel truths that are very far removed from reality, which makes it almost impossible these days to bring people with very different political backgrounds to the same table for an open discussion . . . because they most likely live in entirely different worlds with an entirely different set of rules.

Are you able to pin down at which point “clicks“ turned into a new kind of currency?

MR: I think as soon as Zuckerberg realized how to make some serious money with Facebook this turned into the dominant model for this platform. It’s all about monetization, and that’s why this particular model gets encouraged. Now, it’s embedded in its very own DNA once and for all, it’s designed to permanently sell and alienate. The like button turned into an omnipresent reward system.

But does this particular button still carry the same weight, now that each and everyone knows how to manipulate the numbers?

HB: Obviously the basic requirement – regardless of which platform you’re using – is that you’re taking the whole thing seriously. And if you agree to that the like button is very far from being obsolete. The actual followers are more important to platforms like Instagram but the reward system is the very same. The numbers need to be high because only then your appetite for popularity gets saturated.

How did you get started with The Cleaners? Was this topic something you’d been thinking about for years, or did the issue come to you, so to speak?

MR: In the beginning it was driven by curiosity and by the wish to fully understand how these platforms operate. I remember this case from 2013 where a video with explicit child abuse content found its way onto Facebook. Within a very short amount of time it was shared 16,000 times, and received 4,000 likes. I was very curious about how something like this could’ve happened . . . even more curious why things like this aren’t happening all the time. It became clear that the filtering of unwanted content wasn’t happening via fully automatic algorithms, and that you’d need an armada of employees to do the job, simply because the sheer amount of data that’s getting uploaded on a daily basis is such a surreally large one. That this kind of work is going to be outsourced by big companies for financial reasons is evident – but to where?

We got in contact with American media scientist Dr. Sarah T. Roberts, and she pointed us in the direction of the Philippines. It took us around a year to fully understand this network of outsourcing companies on-site in Manila. What these companies do is offer jobs as data analysts, but as soon as the actual training starts, it becomes very obvious how the land lies: there are codewords for Facebook and there are non-disclosure obligations that won’t even allow you to tell your family what you’re actually doing. It’s all pretty adventurous and connected to a great deal of time and effort just to make sure that the public doesn’t get a clear picture. And these companies use any legal action they can to make sure that this won’t change any time soon. The reasons for that are fairly simple: the user shouldn’t be aware of the fact that the company’s directives are pure interpretation, practiced by someone who got chosen by their mindset and personality, which basically equals qualification in this case.

But why Manila? Is it a matter of standing for ultra-Catholic and pretty conservative values which then will presumably work as a kind of stronghold against the loose morals of the Western world?

HB: That’s what we asked ourselves! The answer then got delivered in the shape of this one promotional video of one outsourcing company where the Philippines were pictured as a country with a similar value system as the West. This gets justified through a brief excursion into the history of the nation, since the Spaniards have been there as a colonial power for 300 years, followed by another hundred years under the American flag. A delivery of cultural values has taken place. These companies are now using the post-colonisation context as a premium location factor. As in: man, we know the sports you like, we know the food you prefer.

MR: And we know about your moral limits. And that’s the actual dilemma of it all because that’s simply not true.

HB: Exactly. It’s the very opposite, indeed. The very majority of the population were raised as devoted Catholics that live their daily lives by faith. You can find verses from the Bible on tees, the local Facebook pages are strongly marked with psalms, and during the Easter week a few deistic ones even get nailed on crosses after being whipped. It’s a very different understanding of religion, where terms such as “sacrifice” are at an all time high. It’s about suffering, it’s about being devoted and about sacrifice, with joy for the salvation of the world. That’s the narrative a lot of employees need to form for themselves, otherwise they wouldn’t be able to do the job. From beheadings to child abuse to torture to terror attacks: if you have to watch the unthinkable for eight to ten hours straight as a content moderator – observing the sins of the world, if you like – within a social-religious context like this, you probably cannot help but feel close to Jesus who died for our sins as well. Cleanliness is next to Godliness. On-site, the big companies find a weird mix of capitalism and religious fervor, which then gets transformed into a perfectly functioning sweatshop.

The menu these content moderators have to work from is partially authored by the US Department of Homeland Security, right?

MR: Yes. At least for everything connected to global terrorism. There’s a line of decision makers involved, actually. Nicole Wong, who was the vice president and deputy general counsel at Google, was giving us some profound insights. She and a handful of other people working on top of the digital food chain got immediately surrounded by NGOs and lobby groups that try their very best to influence certain decisions. We call these consultants of organized civil society, and it feels rather harmless at first when a particular Family Safety Institute tries its best to gain influence on social media platforms . . . it’s rather obvious that you want these platforms to represent a family-friendly environment. The million-dollar-question actually is: Why does it need to be family-friendly? There’s age restriction, so why does it need to be designed to be an unproblematic ride for a six-year-old? I seriously doubt that!

Here’s an example: there’s this London-based project called “Airwars,” which we portray in our film, and they try to archive every image and snippet of film connected to the war in Syria, especially the ones with reports of civilian casualties, before the material gets deleted. Monitoring the coalition air war against ISIS, that’s what they call it. Regular journalists hardly have any access to this material because it gets censored by different interest groups with the result that we only get served what the military wants us to see. The people on-site basically document every incident with their smart phones with the intention of showing a reality far away from what we’re allowed to see in the news. If this material then gets removed because it seems to be way more important to create a “healthy environment” in order to please the Family Safety Program, well, then things start to get really unpleasant because the progressive and democratic potential of these platforms gets infiltrated on purpose. And that’s what we – as members of civil society – need to discuss: What do we want to see ourselves confronted with? How controversial do we want these platforms to be? How comfortable do we want to feel?

But that’s a discussion that’s already happening to a certain degree: it’s a solution that’s missing. Is there still a chance to handle social media platforms differently? In other words: is something like expropriation possible?

HB: Well, that’s something that needs to be thought through at least. The situation we’re dealing with at this very moment is that a lot of the components of each and everyone’s social, analog life gets shifted into digital spheres, which means Facebook is no longer a neat platform where you post the occasional wacky snapshot, it’s the public sphere in the digital arena. It’s where supposedly political debates are happening. It’s the space with a permanent stream of information. The importance of this platform in our democracy is immense, and its impact and significance will probably still grow because people are embracing this fairly new way of cohabitation. The downside of it all is that there’s no inside view, so to speak. No one knows how this new public sphere gets shaped and developed because it is designed by a private company that’s looking after its own interests first and foremost.

You know, when I choose to live in a particular country, there’s a constitution and I know how to conduct myself as an emancipated citizen. There is no such thing in the digital world, there are no real guidelines telling me how to act, and if there are any I’m clueless about who authorized them. There’s no ethical moral codex, there are only lonely decisions made by private companies who even outsource decision-making with sometimes mysterious consequences. Why do we tend to accept that as digital citizens? Why isn’t there a revolution that reconquers the digital space in order to introduce a kind of state sector? Dispossession. Decentralization. That’s what needs to happen next in my humble opinion – and hopefully our film makes a contribution to that.

MR: I believe that dispossession could be the right concept but there are essential institutions missing at this point to make it a reality. Understandably, people are concerned when they hear terms such as “dispossession“ and “decentralization,” it all sounds too close to nationalization, and governmental action is no solution as we’re all very much aware how drastic the digital world can be changed within totalitarian systems. What we need is a civic institution that takes care of the digital arena. Right now, our democratic values are at stake, no doubt about it. If no one is giving in and offers proper alternatives anytime soon it’ll be too late and Facebook will easily strengthen its monopoly position.

The whole topic sure feels like one gigantic bottomless pit. Was it therefore hard for you to find the right rhythm for “The Cleaners“?

HB: There was no elaborate treatment, really, because we didn’t know beforehand which informal sources we’d be able to tap and what would be revealed. Who has the courage to speak in front of the camera and how rich will the generated material be? We spent quite some time in the cutting room in order to check what was missing in order to tell this story in all its facets. We obviously had a few desired candidates like Monika Bickert, but never received any response since the lack of transparency is top priority with Facebook in order to reduce any kind of public debate to the max.

MR: But we’re really proud of our film nevertheless. I particularly like its structure. On the one hand you have “Delete” – what are the consequences when content gets deleted – but over the course of the film things subtly shift towards “Ignore,” showing what happens if these platforms consciously ignore things just to make more money. It wasn’t our intention that the audience leave the theatre all heated up about corporate America, for us it’s much more important to establish a general feeling for this dilemma we’re all facing.

This interview was originally published in Lemonade, a summer special from the team at Lodown Magazine. To purchase a copy, visit the Lodown Shop.

Credits

- Interview: Sven Fortmann

- Images: Konrad Waldmann and Gebrueder Beetz Filmproduktion