Why Europe Could Have Run the 21st Century

|Mark Leonard

In 2006, political scientist Mark Leonard delivered a lecture on Europe as a revolutionary model for the future. In the wake of Brexit, it is poignant, crucial reading.

Winston Churchill famously once said that “To build may have to be the slow and laborious task of years. To destroy can be the thoughtless act of a single day.” With Britain’s membership of the EU, it turned out to be shorter than that: 16 hours of voting was all it took.

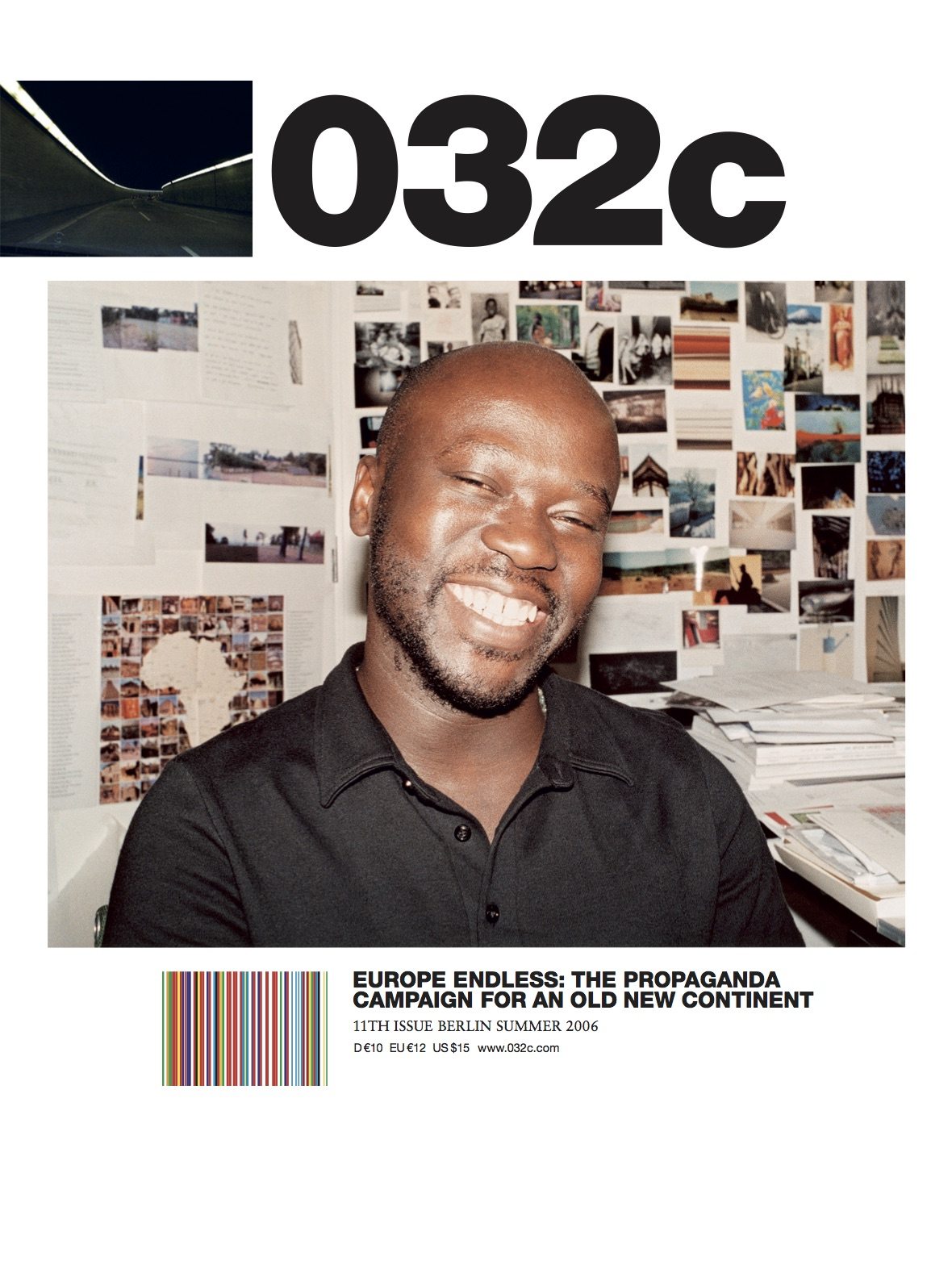

Ten years ago, 032c published issue #11, under the title “Europe Endless: The Propaganda Campaign for an Old New Continent.” At its center was a 58-page dossier of opinion pieces, interviews, and histories of the continent, and its governing body, the EU, with a set of multi-page fold-outs on the history of the European Union, made by Rem Koolhaas and AMO/OMA.

This morning, the first Monday post-Brexit, we are waking up to a new week, in a new world, and one piece from that issue bears more re-reading than any other: Mark Leonard’s “Why Europe Will Run the 21st Century,” originally delivered as a lecture in London. A decade later, with the far-right marching across the continent, the European Union’s bright, borderless, and bureaucratic form seems more utopian than ever.

I’m going to try and do two things this evening. First I’m going to explain why I can come here and talk about the future of Europe and still smile and look optimistic in spite of the sluggish growth in Eurozone economies, the problems that we’re currently experiencing over cartoons and the fact that Jacques Chirac is still President of France! Then I’m going to explain why – even a year after I wrote a book called Why Europe Will Run the 21st Century, a year which has seen “no” votes in France and Holland and the death of Valéry Giscard d’Estaing’s constitutional dream – I still believe that that’s right. I want to offer a few thoughts on how today’s generation of European Union leaders can adapt the European Project to a very different political landscape. So I’ll start with my optimism. In the current climate it’s certainly not an obvious proposition. If you type the words “Europe” and “Crisis” into the Internet search engine Google more than four million entries come up!

The media are so used to using these words together that one could be forgiven for thinking that they are completely interchangeable. Of course that’s because the European Union is most often written about by journalists but if you look at it through the eyes of an historian I think you’ll find a very different story: A story of hidden success behind this journalist’s superficial sense of failure. Historians will look at the European Union as a miracle. In just 50 years a continent has made war between its major powers unthinkable, has moved from having a GDP that was less than half the size of the US’s after the Second World War to one which is roughly the same size.

It has dragged successive waves of countries out of dictatorship and into democracy. It’s wrong to be complacent about the future and not to face up to many of the huge challenges that individual European countries have to grapple with, ranging from how we deal with diversity to reforming the economies and social systems of many of the core countries of the European Union, to how we look again at the institutions of the European Union and modernise dinosaur features like the Common Agricultural Policy. But I think this insistent focus on daily crises and failures has actually hidden a much deeper story of European success. And because it’s journalists rather than historians who report the news we have come to see European power and the power of this extraordinary political project, as weakness. For all the talk of American Empire I think that the last two years have been above all else a demonstration of the limits of American power. Whilst we’ve seen American power humbled on the streets in Fallujah, in many other parts of the world – the UN Security Council and with their traditional allies – we’ve seen the development of a different sort of power in the European Union: A power which works in the long-term and is about reshaping the world rather than winning short-term tussles.

That power can’t be measured in the traditional ways that we thought about power. you can’t capture it simply by looking at military budgets or smart missile technology. It can be captured in treaties, constitutions, laws, and when we stop looking at the world through American eyes we can see that many of the elements of European weakness are in fact facets of this extraordinary kind of power, which I call transformative power. I’m not going to bore you by going through all the different bits of evidence of it. I will focus on four features of that power now before looking at the future.

“If you look at the history of the last 15 years since the end of the Cold War, what you’ve seen is regime change on a scale never before seen in human history but without a single shot having been fired.”

The first feature of European power is that it is pretty easy to miss. It works like an invisible hand through the shell of national political structures. So the British House of Commons, the Spanish Parliament, our law courts, our civil servants are all still there and they look very much as they have done for hundreds of years. But what is extraordinary is the way that they have become agents of the European Union. The laws are often passed by national ministers and civil servants meeting together in Brussels. The Courts enforce these laws and the civil servants who work in different ministries ranging from the Home Office to the Department of Agriculture, are often implementing European policies and giving out European money. The fact that this happens in this subtle way is no accident. By creating common standards that are implemented through national institutions, the European Project has transformed entire countries without becoming a target for hostility – in the way that it would have done had European power been about creating a European state or a European nation.

The same is true for the European Union when it works on the global stage. If you look at European troops around the world they tend to operate under a United Nations or a NATO banner rather than under a European flag, which means that whilst every American company, embassy, and military base has become a terrorist target, a symbol of the American dream, of George Bush’s belief that there is a single, sustainable model of human progress to which all people must aspire and move towards, the European union has an understated perspective and presence on the global stage. And its relative invisibility allows it to spread its influence without the same degree of provocation.

That’s of course related to the fact that Europe does not have a single leader. It’s a network of many centers of power that are held together by common policies, common goals and a common legal framework. This allows the European Union to provide member states like Britain the benefit of being part of the largest single market in the world but without giving up our national identity, our independence, and the political institutions to which we pledge allegiance and which we believe and through which we want to exercise our voice.

But at the same time this structure has also allowed the European Union to play a very different role on the world stage, and to reverse one of the oldest principles of international relations: the balance of power. The rise of the European Union is the first time in history that a great power has arisen without provoking other countries to unite against it. What’s extraordinary about the EU (unlike the British Empire, the French and Spanish Empires, the Germans and Japanese in the 20th century – or even America today) is that the more powerful the European Union becomes the longer the list of countries that want to join it. It’s a magnetic force that people want to unite with rather than balance against.

“It’s a magnetic force that people want to unite with rather than balance against. The worst thing that the European Union can do to countries outside it, is absolutely nothing at all.”

The reason you see this paradox is very closely related to the second feature of European power: When the European Union wants to project power on the global stage (when it wants to assert itself), it doesn’t do it by threatening to invade other countries. In fact the worst thing that the European Union can do to countries outside it, is absolutely nothing at all. The worst thing it can do is close its market, cut off contact, tell them they’ll never be members of this extraordinary club which we’ve been building over the last 50 years. That’s what I call passive aggression.

The prize of European membership has been strong enough to transform a whole series of countries like Spain, Greece, Poland and the Czech Republic and we’re starting to have a similar affect on Turkey today. If you look at the history of the last 15 years since the end of the Cold War, what you’ve seen is regime change on a scale never before seen in human history but without a single shot having been red. The prize of membership is enough to unite the people and the regimes of those countries behind a project of economic, political and social transformation. The only thing worse than having a collection of bureaucrats from Brussels descend upon you if you’re in Turkey or the former Yugoslavia, is the threat of them not turning up and not telling you how to change your political system.

If we look at what’s happened within the European Union, there are already 450 million citizens who live in this union and there are another 1.5 billion people in 80 countries who are umbilically linked to the European Union because we’re their biggest source of trade, their biggest source of aid, their biggest source of credit, their biggest source of foreign investment. And many of these countries have even linked their currencies to the euro. We’ve started to institutionalise our relationships with these countries and to build in clauses about democracy and human rights and proliferation which govern our interactions with them and which make it clear that their access to our market is conditional on their political system. If this process continues through enlargement – through what’s being called the European Neighbourhood Initiative – we could see nearly a third of the world’s population being drawn into what I call The Euro Sphere (Europe’s zone of influence) which is gradually being transformed by the European Project.

To see how amazing this is, is to compare it to the American approach – to its neighbourhood. The European Union is deeply involved in Serbia’s reconstruction and it supports its desire to be rehabilitated as a European state. But if you compare it to the American approach (to Colombia for instance) there is no such hope of integration through multilateral institutions. There are no structural funds. There’s no hope of one day becoming a member of an America club. Instead there’s simply the temporary assistance of American military trading missions, Huey helicopters and aid in the war on drugs. The focus is entirely on the American national interest rather than the democratic transformation of the countries around it. The result in many of these countries is a story of persistent failure with troops being sucked into countries like Haiti and Colombia every ten years to deal with exactly the sorts of problems which they thought they had dealt with last time.

This brings me to the third feature of the European Union, it’s secret weapon: the law. Europe’s obsession with legal frameworks is often seen as the ultimate sign of weakness. one of the most powerful metaphors that came out of the Iraq (Debacle) was the idea of Europe as a modern day Prometheus that had bound itself so tightly in red tape and respect for institutions like the United Nations, that it was incapable of doing anything. But in many ways it’s the obsession with legal frameworks which gives the European Union so much power. It allows it to transform the countries it comes into contact with rather than just skimming the surface. Military power can allow you to change regimes in countries like Iraq and Afghanistan but its legal obsession which has allowed it to change all of Polish society from its economic policies to its property laws to its treatment of minorities, to the food that gets served on the nation’s table. Every country that joins the European Union has to absorb 80 thousand pages of laws in 31 volumes that govern everything from gay rights to food safety in order to be part of this club. Whilst the lonely superpower can bribe and bully and impose its will almost anywhere in the world, as soon as it turns its back its potency starts to wane. Whereas within the European Union strength is as deep as it is broad. Once people are sucked into this legal community, they’ve changed forever because it’s national parliament who vote through the laws that allow them to be part of the European club.

This brings me to the fourth point about Europe. It is starting to change the nature of the rules of the world beyond the European region. Today in every single corner of the world there are countries that are drawing inspiration from the European model and they’re nurturing their own neighbourhood club. If you go to East Asia (as I do every couple of months) you can see that the big debates are about the idea of an East Asian community modelled on the European Union with its own single market and one day even, potentially its own currency. In Latin America they’re talking about Menti-culture; in Africa they’ve created the African Union which is explicitly modelled on the European Union. In the Arab world they’re talking about ways of turning the Arab League into a regional community which could give its members access to the same benefits that European countries have drawn from being in the European Union.

Coupled with this is the fact that the EU has become one of the only powers on the global stage that is interested in building global institutions. After the chaos of World War II it was the United States that took the lead in creating the Bretton Woods Institutions which gave us so much stability and peace during the Cold War. But the United States is no longer playing that role under the Bush Administration. It’s the European Union which has been creating the next generation of institutions which reflect its obsession with law; its belief in multilateral institutions and its way of doing business. It was Europeans who initiated the World Trade Organisation and the indefatigable former European Commissioner Peter Sutherland. It was Europeans who pressed ahead with the creation of the International Criminal Court after the Bush Administration announced it was dead and refused to have anything to do with it. It was Europeans who have kept Kyoto alive and forced the Russians to ratify it long after Condi Rice said that it was dead. In that way Europeans are starting to develop rules for the world which reflect the basic principles which have worked so well in our own continent.

We’re beginning to see a ‘regional domino’ effect that is redefining what power means in the 21st century. As we look forward, we see that this century is neither going to be run by a unipolar United States, nor by a world government modelled on the United Nations but by a series of overlapping interdependent clubs that are committed to the rule of law, to mutual interference in each other’s internal affairs and to legal ways of dealing with dispute.

The European Project has been genuinely disruptive to world order. If you go back 500 years it was Europeans who invented the most effective form of political organisation in history. The nation state was so effective that it very quickly wiped out all other ways of organising politics at that time. And countries which were not nation states at that time were faced with a very stark choice, either to become a nation state themselves or to get taken over by one.

Fifty years ago the Europeans went back to the drawing board and reinvented this model, creating the European Union and the net result is that people in every other continent – people outside the EU – are having to choose either to join the European Union or to develop their own neighbourhood club based on the same principles. As this process continues we’ll see the emergence of what I call a new European century, not because Europe will run the world as an empire or because European economies will be the biggest in the world, but because the European way of doing things will have become the world’s.

Now of course I was making this argument before the French and Dutch referendums last year and many people have said to me (quite legitimately), “How can Europe hope to run a century if it can’t even agree on its own constitution?” It’s a fair question. The French and Dutch votes swept through Europe’s political class like a tsunami destroying political careers, emasculating the Constitutional Treaty and putting a full stop on a 20-year process of European Integration from above, which began when Jacques Delor started planning the single market. But I think the European Project itself is neither dead nor dying. It’s just changing.

I’d like to present a few untested ideas about how Europe’s political class can adapt to these new circumstances. For 50 years within the EU the main argument between politicians in Brussels was about what kind of body they were creating. Some people wanted to create a federal state modelled on a national level, but executed on a European continental scale. Other people wanted to create something that looked more like a ‘free trade’ area. The people involved in these arguments were very few. Ordinary citizens felt that as long as the European Union made them richer and safer, they trust governments to work out the details.

Progress during this period of time was measured in terms of the number of signed treaties, because Europe was in a construction phase. They were building a single market, a single currency, and a common foreign security policy from nothing.

Because the countries within the European Union were relatively similar, the assumption was that a ‘one size fits all’ model of the European Union would be the right one, with some countries taking a bit longer to catch up. There were two dominant models. One – as I said – was inspired by the Italian MEP Altiero Spinelli who wanted to create this constitutional structure for Europe. The other way forward was inspired by Jean Monnet, the founder of the European Union, who thought that you could build discreetly, issue by issue, without involving the public.

Today, since the ‘no votes’ we’ve seen the return of these two groups. The federalists led by the Luxembourg Prime Minister Jean- Claude Juncker, think that we can simply ignore the French and Dutch votes; we can carry on as if they never happened. 13 countries have already ratified the treaties. If another seven can do it they’ll have 80% of the countries behind it. They can then ask the French and Dutch to reconsider their opinions and maybe attach a social declaration explaining why the European Union isn’t going to destroy the French social model and hopefully the French and Dutch voters will come round and realise the error of their ways.

On the other hand there are a group of people led by the French who are echoing the Monnet method. They’re incrementalists. They think that we can save the most important bits of the treaty like the composition of the commission and the voting waits and the idea of European Foreign Minister, but make it look less constitutional and get national parliaments to ratify it so there aren’t any more popular votes.

The timetable is for 2008 / 2009, when Croatia joins the European Union. All national parliaments will have to ratify Croatia’s succession. They could add on an additional protocol with these new bits of the treaty which they will save from the body of the text. That way of thinking about Europe is fundamentally challenged by the changes that we’ve seen in the last few years. First of all when the European Union spreads all the way from the West Coast of Ireland to hopefully one day, Istanbul on the East, and when it goes from Arctic Circle down to the Strap of Spain, there’s so much diversity that this idea of a ‘one size fits all’ approach will forever be challenged in the long-term.

Secondly we’ve seen a major change in the political landscape of the European Union. Many countries have started holding referendums on new treaties. The EU is now facing a political situation where governments are not trusted, where people are not willing to contract out their decision to their leaders.

Thirdly I think there is a delivery deficit in the European Union. If you look at the polls, most European citizens share common concerns. Most European citizens want the European Union to deal with the issues that they don’t want their national governments to deal with on their own – whether it’s tackling climate change and pollution or helping guarantee security on the global stage, or getting the European economy back on track. At the same time the credibility of the European Project to make a difference has all but disappeared. And anxiety about enlargement, about economic reform and globalisation are all deep scenes which can be exploited by populace.

To get back on track, we need to develop a new way of thinking about European Integration, which is for a mature Europe: political, not technocratic, diverse, and about delivering for ordinary citizens rather than being built from scratch. In order to achieve that, three things must be done.

First of all, declare a moratorium on new treaties. The problem with the European Constitution is that it failed to meet the most basic test of European Integration in the past, which is finding practical ways of dealing with Europe-wide problems rather than being driven by an ideology of ever-closer union. I think European leaders should declare a five-year moratorium on any new treaties. But instead of presenting that as a Eurosceptic move they should use it to make Europe stronger and more effective by focusing on things we all know need to be done at a European level: foreign policy, migration, terrorism and completing the single market.

“The European Union is as convincing an answer in the 21st century to globalisation as it was to the problem of war in the 20th century.”

The second thing we need to do is to consider how we change Europe in the future. In the past we’ve had a series of intergovernmental conferences behind closed doors where they produced these treaties which govern everything from voting waits to the powers of the European Commission, things which bear no resemblance to the problems of peoples’ everyday lives. And when it comes to a vote as it did in France and Holland this time, these vast treaties simply become a receptacle for discontent. I think the European Union needs to move forward by developing much narrower packages of reform which deliver concrete objectives such as improving our ability to deal with globalisation, or giving Javier Solana, the European High Representative for Foreign Affairs, the power he needs to be able to deal with China, India and the US in an effective way.

The third response is we need to lose this idea of a single European Union and move towards an notion of many Europes, the Eurozone. In the future I think that European Integration is going to be driven by clubs of countries coming together behind specific goals, rather ‘one size fits all’ solutions. They may develop deeper integration around their tax basis, come together around a defense community, or the countries in the Schengen Agreement who’ve abolished border controls may develop new ways of handling security.

We’ll also have to develop a much more flexible offer that doesn’t offer Turkey or Georgia or Ukraine exactly the same thing, but comes up with a package of things which are attractive to them and relevant to their immediate needs. We need to inspire European citizens with a different sense of what the EU is about. Not simply presenting it to them as a tangle of bureaucracy, of treaties, of laws. Nor the idea of a European dream to one day look like the United States of America.

Instead we need to use the failure of the constitution in France and Holland to move forward to a different and more democratic and political European Union, because what we saw in the debates in France and Holland is that the old debate of Europe (right or wrong) is coming to an end and is being replaced by another debate between differing visions of the European Union; right or left rather than right or wrong. In a way that’s how political and economic unions mature.

For the pioneers of the European Coal and Steel Community in 1951 the memories of war were fresh and the European Project was fragile. It was like a bicycle that need constant pedaling. But 50 years on, a French or a Dutch ‘no’ does not wipe out half a century of European Integration. With these 80 thousand pages of law, a common market, a single currency and an increasingly common Defense Force that served in Bosnia, Macedonia, the democratic Republic of Congo, the European Union is here to stay, but it’s going to become a political battleground in which individuals from around the European Union come forward with different ideas. And these arguments will I think bring strength to Europe rather than destroy it. There is a battle line which has been drawn between those who oppose enlargement and reform and those who see Europe doing best by looking outwards, and reforming outdated institutions like the Common Agricultural Policy. My book is very much a contribution to that wider debate. It’s a manifesto for a self-confident, outward-looking European Union that is global in its interests and above all, in its sense of responsibility. When I call for a project for a new European century, I’m talking about an EU that’s capable of reforming its economies and social models for an age of globalisation; giving Europe a voice in the world with a foreign minister and a diplomatic service; opening Europe’s borders to manage migration; tackling environmental challenges beyond Kyoto; continuing to enlarge and developing policies to transform Europe’s new neighbours. And to do this in a way that has won the support of its citizens by declaring a five-year moratorium on treaty change, and increasing the role of national parliaments and national democracy. I’m convinced if we can do that, then the net result of the crises of the last year will be the foundation for a new era of European Integration in which the European Union is as convincing an answer in the 21st century to globalisation as it was to the problem of war in the 20th century.

QUESTIONS FROM THE AUDIENCE

CHARLES JENCKS: I think your metaphors are interesting about network and clubs and passive aggression. As metaphors of course, we choose them and then they choose us. It reminds me rather of the idea of The Hidden Hand because a lot of your metaphors for running, imply that running is power, or running is controlling but you’re not using the word ‘run’ in that sense; you’re using it in an economic sense, ‘hidden hand.’ If those are the metaphors then as Ruskin said, “When we look at civilisations in countries we can judge them by their architecture.” You can see where I’m going! And if we go to Berlaymont the centre of power in Brussels and we look at the building which took 20 years to refurbish at a cost of £130m and if we look at Strasbourg and all the other architecture of the European Union it really is the most bureaucratic, ugly, offensive, bad neighbourly club you’d ever not want to join, even if you were invited. What do you have to say about the cultural, architectural and expressive qualities of the EU, and are they not those of a coal union who wants to hide its head behind laws in a stealthy passive-aggressive way?

MARK LEONARD: Whenever people bring architectural metaphors into a discussion of the European Union I know that we’re in trouble because the central metaphor which has done so much damage to the European debate is this idea of the European Union as a federal house half built where the Eurosceptics want to pull it down and the federalists want to just put the roof on and get ourselves a directly elected president. And so many of the metaphors that have destroyed discussions about the European Union have been drawn from this idea of architecture and building. Then as you say, anyone who went to visit Brussels or Strasbourg and was given a guided tour of the European institutions would be even more depressed than those who’d taken part in these academic seminars about what the EU is going to be. I think in many ways – that brings me back to the heart of the arguments about Europe as a network, because if Europe is a network then the place to look is not Brussels. And the buildings to look at are not the Berlaymont and the European Parliament building. They’re the Eiffel Tower, the London Eye. They’re going to Bilbao and looking at Frank Gehry’s buildings that you’ve written about so elegantly. I took part in a very interesting project with a friend of mine, Rem Koolhaas. He was asked by Romano Prodi, who was then President at the European Commission, to think about the architecture of Brussels and what Brussels should look like as a Capital of Europe. I helped him think about what the EU is as a political system.

One of the most interesting things to come out of it was a way of thinking about the EU which wasn’t about the sort of monolithic blue of the European Flag and the soft megalomania of Brussels’ European Parliament building and Berlaymont. It was trying to come up with a way of representing what was best about Europe’s nations within Brussels, and almost razing it down. It was an effort at making the National Embassies visible, rather than the European Union; they are the ones making the decisions on the European Council. And he came up with a symbol for Europe, which was the idea of a barcode made up of all the European flags, so that when you look at a symbol for Europe you see yourself reflected in it. And you see the Technicolor glory of Europe’s cultural identity reflected back at you, rather than the sort of deadening blue of a at ‘one size fits all’ iconography. I think that that’s absolutely right. It shows the direction that we need to move in, and the real need to start developing different metaphors, different models, and a whole different vocabulary to describe the European Project, one which isn’t drawn from 18th century European nation-building exercises which were about flags and anthems and passports, but are in fact about proud countries working together in an era of globalization. There is a huge bank of cultural richness to draw on, rather than trying to force everything into a single blueprint.

“We hope vaguely; we dread precisely.”

Maybe the challenge is to try and find an architecture which reflects that. There’s a quote from Paul Valery which I think is the best description of European Integration over the last 50 years. He says in six words exactly what millions of people have tried to do when they’re writing about the European Project. He says, “We hope vaguely; we dread precisely.” In other words the Eu is not the product of a beautiful dream of the future. It draws its energy from the negative experiences of World Wars and failure that we’re trying to run away from.

But we have this vague hope of where we’re going, and maybe the challenge for European iconography is to nd some way of hoping vaguely, but representing very precisely what the different components of the Eu are. And those are national compo- nents rather than some kind of Esperanto European identity, whether it’s architectural or cultural.

NEIL O’BRIEN: You said that in the referendums in France and Holland the constitution had become a receptacle for anger. do you accept that that was a vote against integration or are you straying into the dangerous territory of saying that it was really just averse about discontent?

The second question is that what strikes me about your argument about running the 21st century is that it’s essentially backward-looking. The proof for it is Europe’s enlargement. But enlargement now seems to be stalled because voters in France will vote against Turkish entry. Another argument is the argument about a large economy and even the European Commission has published forecasts showing that its share of the world economy will shrink by almost half by mid-century. And that reduces Europe’s power, influence and clout around the world. And it seems to me, fundamentally that the rest of the world is not copying the European template.

Other areas in the world are forming ‘free trade’ areas; they’re not forming customs unions. China and India are not going to give up control of their trade policy, and it seems to me that the idea about transformative power only applies to countries that are going to join the European Union. We haven’t managed to transform Belarus. We certainly haven’t managed to transform Iran. So if only countries joining the European Union are transformed, and there isn’t going to be further enlargement to countries like Turkey, then how are we going to run the 21st century?

MARK SWANN: I’ve read the book; I’ve seen the talk; I haven’t won the T-shirt yet, but I have to say I’m totally sold on the idea of the replication of the European model. My question builds on the previous question. When we look to our eastern borders, Belarus, Ukraine, Russia, is it likely on the horizon of the 21st century time-wise that they’ll either join our club or they’ll form their own club?

RICKY HO: What do you think of the view that in the 21st century the real power is not within a country but is within transnational corporation? There’s a lot of talk about labour market reform and physical policy. Is it not another way of saying, “We are fixing the rule book so as to attract transnational corporation.” If say Goldman Sachs doesn’t like your tax regulation they can quite easily move their capital to another country and that is another form of what you call passive resistance.

MARK LEONARD: Three very big questions. The first was ‘Were the French and Dutch not voting against integration?’ Some of them were, but if you look at the opinion polls the detailed analyses which were done in Holland and France after the votes, they showed that there wasn’t a single reason why people voted ‘no,’ that there were many reasons why people voted ‘no.’ But actually most of the people who voted ‘no’ would categorise themselves as pro-Europeans. The polls showed that 90% of people (both in France and in Holland) wanted to stay in the European Union. So it wasn’t a vote against being in the European Union. Then when they asked people more complex questions you got a mix of reasons. The most common reason in France to vote ‘no’ was because people didn’t like Jacques Chirac and the Government. And then after that you had a whole series of other reasons. That was 40%. About 30% thought that they were voting ‘no’ because they thought that Europe was too neo-liberal and that it was going to undermine the French social model. About 20% didn’t like enlargement. About 13% were voting ‘no’ because of Turkey. You had a similar thing in Holland.

It’s quite a convincing answer to your second question, which is are all European Projects going to go wrong in the future; all the things that I said were good aren’t going to work. Enlargement is a brilliant way of transforming countries only we’re not going to do it anymore. The economy can’t grow if we don’t have enlargement and we’re not going to be able to influence countries that aren’t able to engage with the European Union.

But actually what was very striking about those polls was that people weren’t as hostile to enlargement as initially thought. What’s been quite striking is that everyone said enlargement was dead immediately afterwards, and then within a short period of time we’ve agreed to start talks with Turkey; we’ve con rmed that Romania and Bulgaria are actually going to join; we’ve put membership on the table for Macedonia, and people are starting to think very seriously about how the European Union can rehabilitate itself in the Western Balkans where the European dream was almost killed by the failure to deal with the break-up of Yugoslavia in the 1990s. It’s quite likely that all of these countries are going to be in the European Union.

So then it brings you to the question of what do we do with places like Belarus or Maldives or Ukraine or Georgia if these countries progressed to being labelled democracies that are capable of playing a part in the European club? There’s certainly no enthusiasm for any of these countries to join the EU now. There was no enthusiasm for enlargement after Spain and Portugal joined. People said that if it got any wider it couldn’t get any deeper. Its final borders had been reached. If you spoke to people in 1988 about the idea that the Czech Republic and Poland would be in the European Union they would have thought you were completely mad. I think it takes a while to digest what we’ve done. We’ve just done something quite extraordinary and completely changed our mental map of what Europe is. We’ve reunited a continent, and it’s going to take a while for us to adapt to that. It might take 10 or 15 years before people are ready for further enlargement, but during that process the countries that are around us will change.

The Turkey that gets into the European Union in 15 years’ time will be a very different Turkey from the Turkey that has started negotiating with us now. It will carry on this extraordinary process of reforms that it’s already done. We’ve seen eight packages of reform go through the Turkish Parliament just because they want to get into the European Union. They’ve abolished the death penalty; they’ve started giving minorities like Kurds their own language television and ability to learn in their own languages. And those things will continue.

“We’ve just done something quite extraordinary and completely changed our mental map of what Europe is. We’ve reunited a continent.”

So I actually think it’s a process that will go on in fits and starts. But the reason it will continue is because we realize that if we care about our safety and our security, we can’t simply erect a new Berlin Wall to try and shut out the rest of the world. We’re going to have to engage with our neighbours and we’ll do a lot better if they’re prosperous and they’re liberal democratic and they’re part of the club and we can sell them goods and services, than if they’re outside and unstable and ruled by dictatorships. That’s why I hope that we can actually do more to help countries like Georgia and Ukraine that went through extraordinary political changes in the last couple of years to fulfil the dreams of their citizens and to one day, be in the EU. But it’s going to be a very long-term process. And it’s something which is unprecedented in history. I mean what we’ve just done in Central and Eastern Europe has really never happened before. There have been empires built before. Countries have been invaded and brought into political spaces. But the democratic transformation of 10 countries with 100 million people without a single shot being red in less than 15 years is pretty extraordinary and it will take some time to digest.

That brings me to the third question about transnational capital and whether real power in the 20th century will be wielded by states, or by companies, or I suppose you could say by other non-state actors like Al Qaeda and Osama bin Ladin.

You are right that we are increasingly facing up to the fact that many of the biggest threats of the 21st century are not those that we faced in the 20th century. It does tend to come from non-State actors. Whether it’s climate change being brought about as a result of the behaviour of companies; whether it’s terrorism; whether it’s the consequences of genocide as groups of people go wild, not necessarily sanctioned by national governments, but create chaos that flows beyond its borders. What we’re trying to do is to work out how one can bring a degree of order and regulation to a world where destruction has been privatised, and individuals can wreak chaos from their bedrooms by hacking into computer systems; where NGOs and terrorist organisations and companies can organize things on a global scale, thanks to new technologies.

In that world, again I think we’re going to find that the best way is through bodies like the European Union which are able to get states to club together and to work against, both to make the most out of the opportunities of globalisation but also to deal with the dark side of it.

The only way of having any control over transnational capital is for countries to come together and create a market that’s so big and so attractive that exit is not an option. There are many reasons why Goldman Sachs isn’t going to up sticks and move its offices out of the City of London. It will want to be in the European Union, which is the biggest single market in the world.

Credits

- Text: Mark Leonard