Obituary: The Last Estate of BROOMBERG & CHANARIN

|Olivia Gideon-Thomson

This weekend the Contemporary Art Centre of Barcelona opened The Late Estate Broomberg and Chanarin, a posthumous retrospective of photographers ADAM BROOMBERG and OLIVER CHANARIN’s 23-year collaborative career. As part of their symbolic laying to rest of their life and work as a duo, the artists asked individuals who have marked and witnessed their creative partnership to write a series of obituaries, to be placed in a selection of art and culture publications on the occasion of the exhibition – not their final show together, but their first as an entity officially pronounced “dead.” Here, OLIVIA GIDEON-THOMSON, founder and director of We Folk agency and longtime friend and colleague of A&O, as she calls them below, reflects upon the vibrancy and vicissitudes of more than two decades of dialogue – and considers the meaning of an end.

As with most beginnings, things are a little hazy. How did we end up working together, being friends for so long? How did we survive it?

There are a few moments of clarity that have formed my version of the narrative. I am not sure if these are completely true, and I don’t think it matters much.

They were sitting on a step outside the Blue Note in Hoxton Square, London. Not on the steps leading up to the door, but on a step around the side of the building – the one by the door where men would probably go to take a leak.

There was a group of them, laughing and just hanging out. It was probably 1999. I don’t know why we stopped there, but I was with someone who usually drew attention and I remember just hanging around in the background, a bit annoyed and a bit bored. Suddenly an inquisitive, smiling face turned to me and said, “Who are you?” That was Adam. Someone who I have now known for more than 20 years. Someone I have always had a deep feeling of being seen by.

Olly was also there that day, but I didn’t meet him until later – the following week, or sometime after. They came to a meeting in the office of the agency where I worked at the time: Ziggi Golding’s famous Z Photographic, the temporary home of such luminaries such as Juergen Teller, Dana Lixenberg, Stefan Ruiz, and Katie Grand. Run in London by Katy Baggott, who was my boss until 2000 and my friend until her death in 2009, Z was my first job in the business. The boys didn’t cut much ice with Katy, but we managed to make it through a meeting. They arrived with a pile of prints in no order. I was probably asked to do the meeting so as not to be rude. I think Adam remembers what I said to them, but I don’t. I do remember being charmed – they were both incredibly funny. Handsome, yes, but also kind of different. What they had was an energy, dynamic and self-deprecating mixed with the chutzpah it takes to claim space. This has always been their greatest weapon, and the source of the strongest criticism against them – of the Who the f**k do they think they are? response.

At some point in the early 2000s, as the agency disintegrated and the relationships that had been formed there splintered, I suddenly found myself able to think about working with new artists, and on my own terms. I don’t remember this, but I must have worked with them freelance and then taken them into Bill Charles, an agency that had a big roster of color photographers from the US: Stephen Shore, Jeff Mermelstein, Joel Sternfeld, and, later, Larry Sultan. We were working on big campaigns with art directors and creatives who loved working with artists. A&O had been commissioned by Fallon for an out-of-home campaign for Sony, and this had put them on the ad map. Their portraiture was born and developed in the program of Fabrica (Toscani’s baby) and Colors magazine alongside people who mentored them and helped develop their eye, Stefan Ruiz for example. They became the editors of Colors, making the work that would become their first published book of note: GHETTO (Trolley Books, 2003). There was a boom, at the time, of photographers moving between serious journalistic and lighter commercial work, and they were at the epicenter of the cross-over. A little later we secured a solo show at the Photographers Gallery, then under Charlotte Cotton’s guiding hand. I remember the lunch where she asked me if they were to be trusted – if she could count on them, is what I think she meant. Everyone wanted a piece of them.

Eventually, at an art dinner, I overheard a curator ask someone, “Why do they need an agent?”

The moment I walked into The Day That Nobody Died, their 2008 show at Paradise Row in London, I thought, “Well, that’s me screwed.” In advertising, you can exist for a few years from one or two strong projects. That’s enough time for the brands and creatives you want to keep wanting you back. After a while, if you stop creating new ways for them to use you, things can taper off. This project was that moment, a pivot point. A Janus moment of looking back and looking forward.

For those of you who don’t know, TDTND was a project involved following a box of rolled up photographic paper on a journey from London to Afghanistan. The work presented was a series of exposures of that paper to the sun. Using the back of a Jeep as a camera, they exposed at the exact places where soldiers had been killed in Afghanistan’s Helmand Province in 2008. As artists embedded within the army, they were probably expected to produce heroic, or at least documentary images. Instead they made something abstract, untenable, somewhat controversial. The results were beautiful and elegant, but that wasn’t the point. Critics found them to be hostile to the process of truth, grief, and heroism. Yet as we learn about returning soldiers struggling with PTSD, we might imagine color fields as strangely truthful representations of the experience of war and returning from it – memories that lack the clarity and sharpness of a documentary lens. For me, TDTND symbolized an important move away from representation, and the commercial application of their work died.

We did continue to work together after that, always loyal and always talking big plans. But I knew their hearts were not in the commercial world. Eventually, at an art dinner, I overheard a curator ask someone, “Why do they need an agent?” At which point I realized – with a bit of relief – that I might be limiting their career by being so visibly part of it. I remember Olly very carefully agreeing with me that perhaps it was time to release each other and for them to fully expand elsewhere. We have remained friends since then, keeping in and out of touch in that way that is possible when the bonds formed are strong. Not always easy – in fact often directly challenging – their own friendship, between A&O, enabled them to make work that is variously politically charged and confrontational, but also sometimes just beautiful. It was behind the blood, sweat, and tears; the broken hearts; the mess of life and the making of art alongside it – behind the fun, the humor, and the irresistible feeling of coming home that inhabited what they created.

I hold in my heart the night of Adam and Sarah’s wedding on a small island off the coast of Cadaques. I had missed the last boat home and did not want to be stuck there all night as everyone descended into getting very high. (I had a small child.) Olly and a friend came to my rescue and rowed me across the dark water back to land. I was holding my son, my husband was blissfully drunk, and Larry, their great friend, asked something of me that made Olly say as though to himself: “This woman, what a woman.” I was so surprised that I had had any effect on Olly at all. But that is just like him, just like them: deeply private, for all their showmanship. To stop working together, to do something so clear, and to make this statement now, at a time of great confusion, is a testament to a kind of maturity, nourished through and above the drama, the parties, the stories, the love affairs. It is right to end this part of the story. And it is hard to let go of something that holds a lifetime of meaning. Most of us don’t manage it.

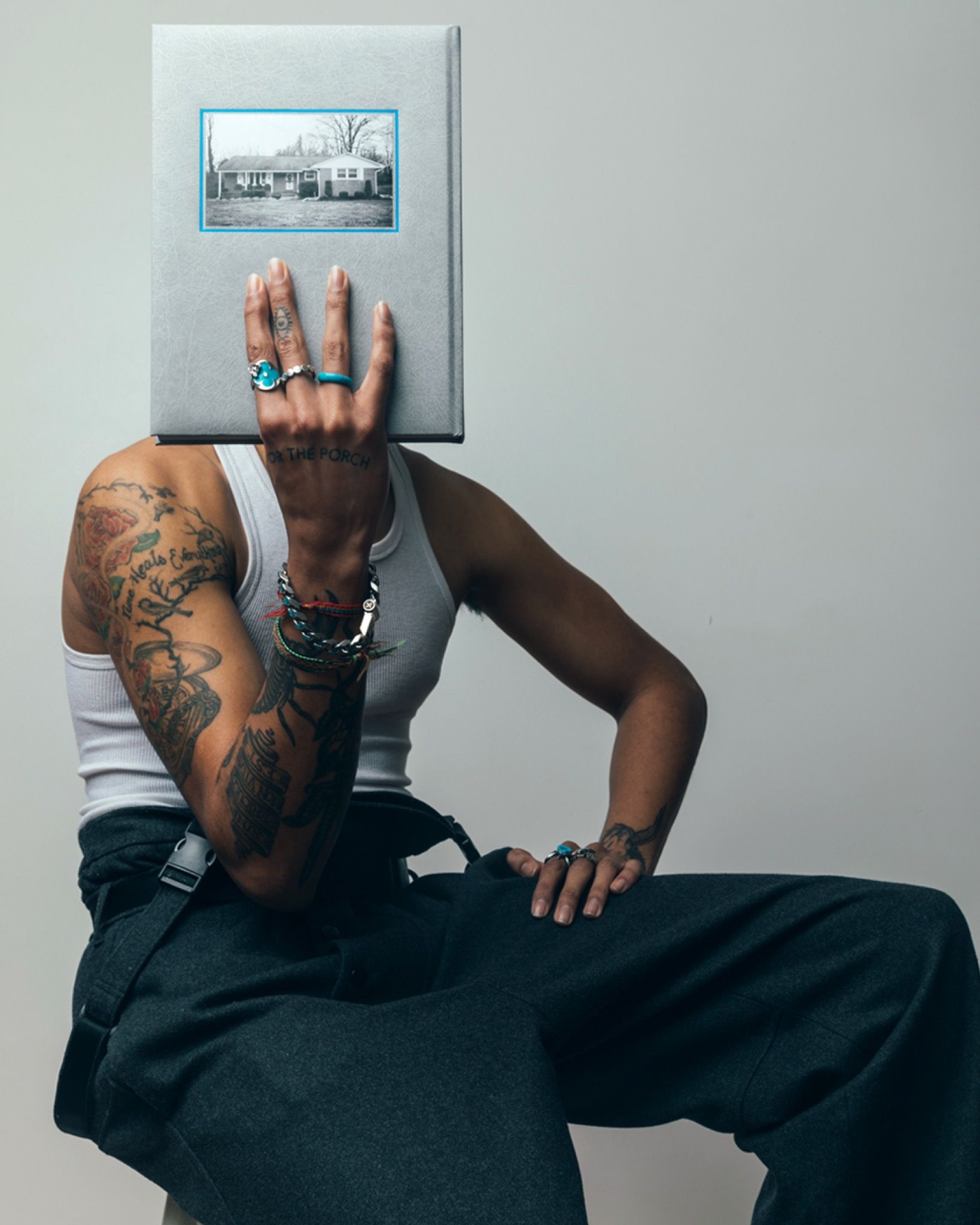

Adam Broomberg (Johannesburg, 1970) and Oliver Chanarin (London, 1971) have worked in a forensic and paranoid interrogation of the photographic medium, in search of everything cultural, emotional, political and economic that governs the currency of images. They have received numerous awards, including the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize (UK), the Infinity Award for Publication (USA), and the Arles Photo-text Book Award (France), and their work is included in private and public collections, including MoMA, Tate Modern and Centre Pompidou. Their first posthumous retrospective, The Late Estate Broomberg and Chanarin, is on view at the Contemporary Art Centre of Barcelona through May 23, 2021. Read more here.