New Prototypes

|CLAIRE KORON ELAT

A prototype is an early sample, model, or release of a product built to test a concept or process. Prototypes is also the Zurich-based brand, founded by Laura Beham and Callum Pidgeon, that did not choose this name serendipitously.

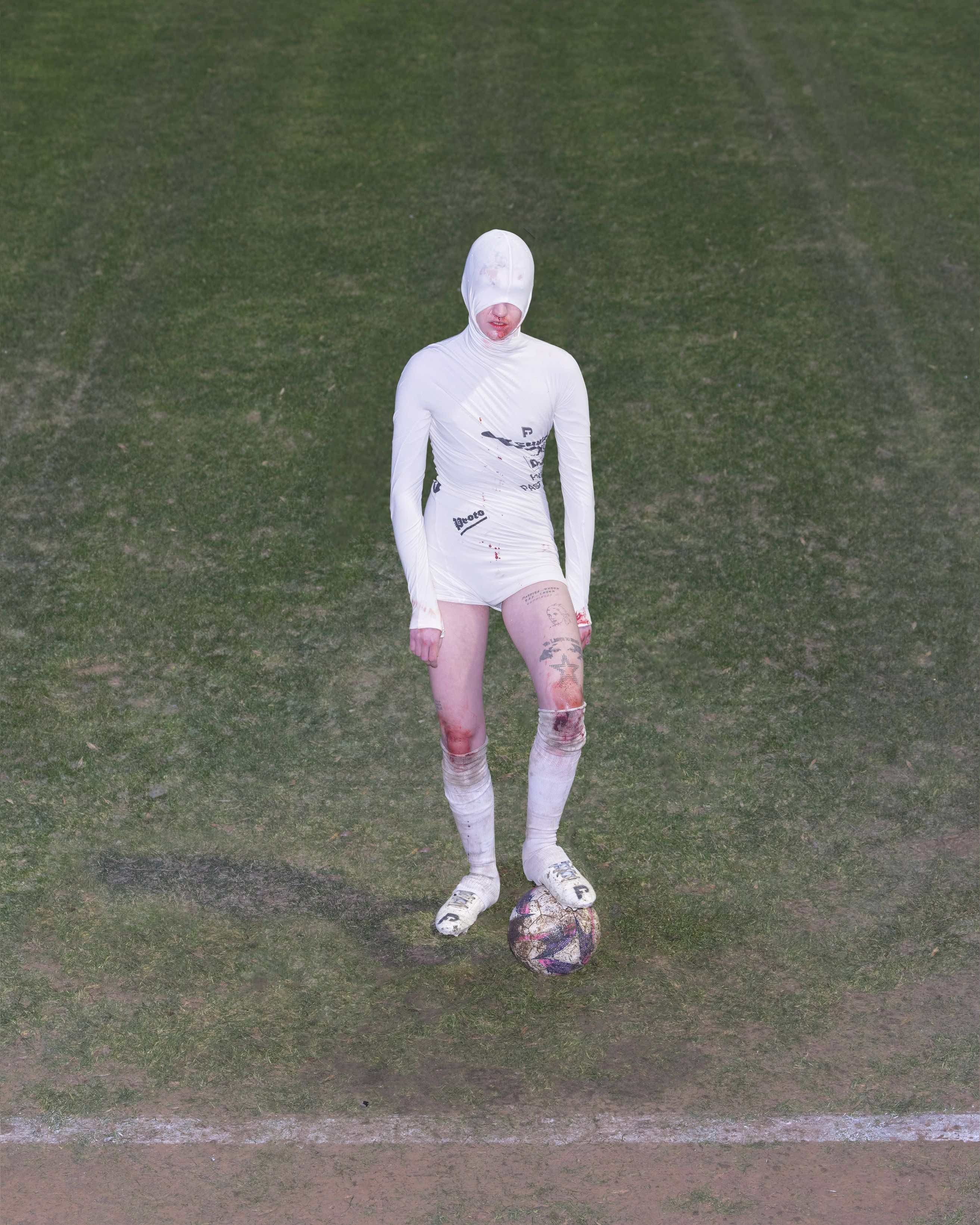

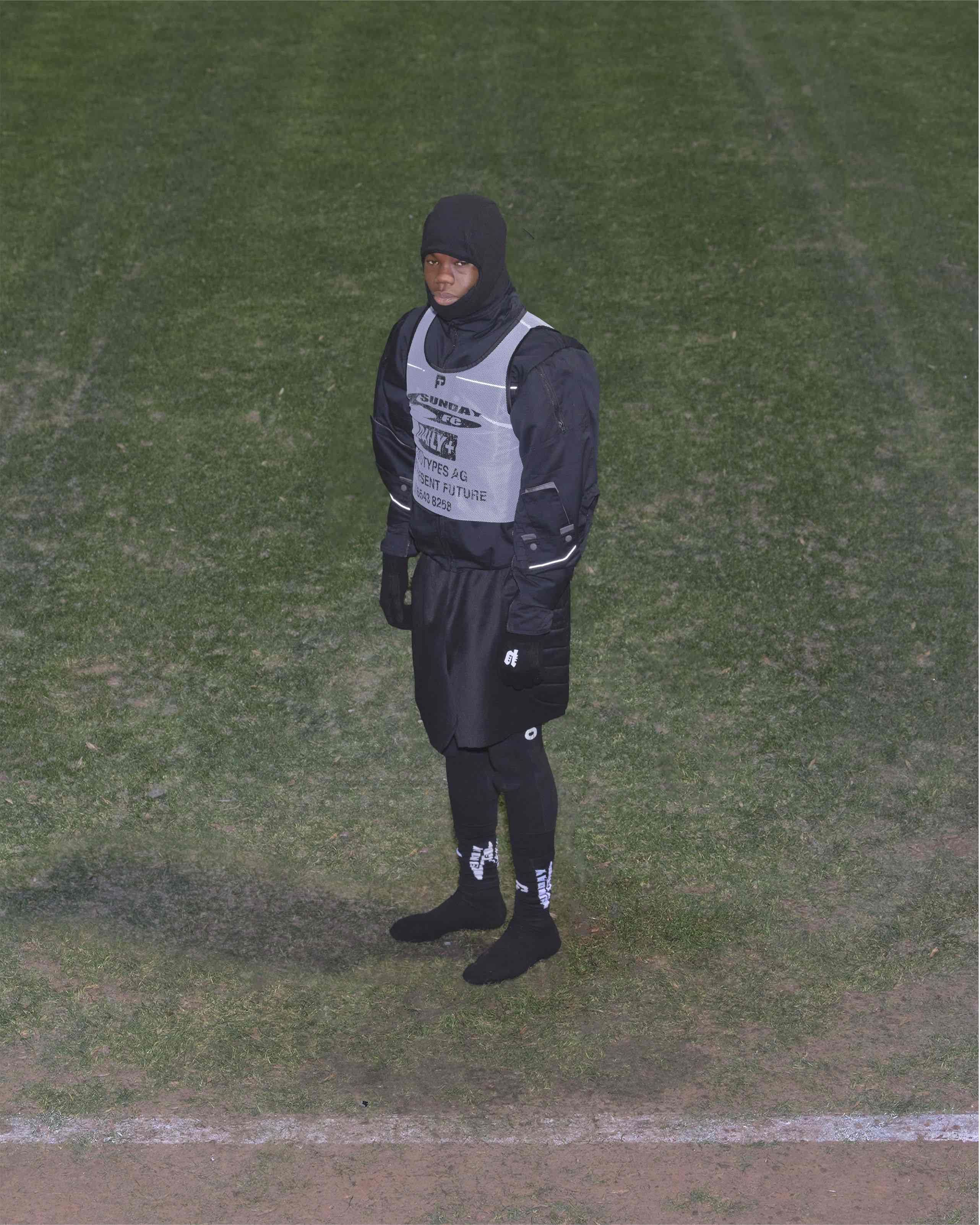

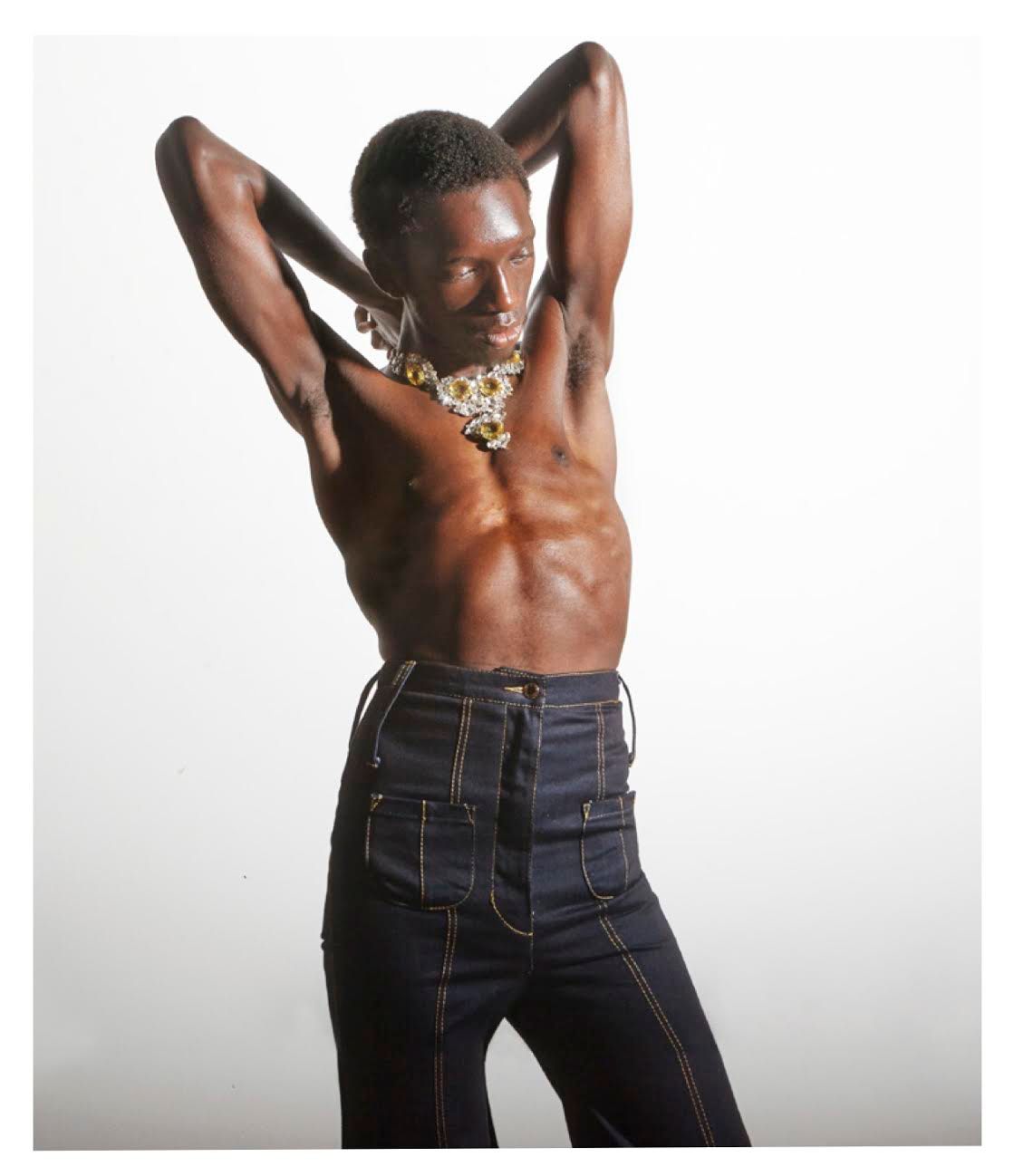

On their website, (future) customers can download Proto Prints that can be ironed onto any clothing piece and Proto Packs, a manual and sewing pattern that allows you to produce your own “Prototypes piece.” Beham and Pidgeon’s attempt to make the luxury fashion market democratic and accessible is being further continued by taking repurposing and up-cycling as their guiding design principles. Their new AW-24 collection Series 06 is an ode to football as a tool of unification, consisting of mostly upcycled sportswear. In conversation with Claire Koron Elat, the two talk about the right forms of appropriation, supposedly gentrifying a working-class aesthetic and the scam of vegan leather.

CLAIRE KORON ELAT: For the production of your garments, you use deadstock fabrics and old clothing. I read a description of your brand that included the sentence “out with the new and in with the old,” which reminded me of one of our past dossiers where the argument is that it’s basically impossible to produce new things in our current cultural state. What’s new is actually old, so we’re returning to tradition.

LAURA BEHAM: “Out with the new” is referring to the general mindset/trend of cherishing the past for its history, traditions, and values. For the past decades, the fashion industry created an image of consume, “The more the better!” This has created endless waste. In my opinion, the role of a designer has changed and working with decommissioned material doesn’t mean you can’t make something original. What can you make out of a pair of pants? It doesn’t have to be pants again. For us the question is: Can we value what we are already have and turn it into something fun and potentially original? The possibilities are not endless but there are plenty.

CKE: It’s obviously difficult to reinvent pants, and I’d say that no one will accuse anyone of stealing or appropriating if you design another “new” pair of pants. Yet stealing and appropriating is a big topic in fashion, especially on social media, with accounts such as Diet Prada.

LB: In a positive light, appropriation—acknowledging to be inspired by something or someone—is the highest form of a compliment, paying homage to something that already exists. Like a Duchamp readymade. When we up-cycle, we leave reminder marks that this used to be something else. It’s not about stealing but about being inspired by others. Actual stealing or copying is just a bad form of appropriation, you’re not even making the effort to try to make it your own. For example, if I love a picture, and I want to have exactly that picture, I force myself to look at it really precisely and ask myself, “What would I change? What do I not like about it?” Eliminating and exchanging elements that don’t feel like you are evolution.

Everyone’s brain is triggered by different things. Hiding that or pretending that nobody inspired you is silly. Our brand name refers to a prototype—which is an early sample, model, or release of a product built to test a concept or process. A prototype is generally used to evaluate a new design to enhance precision. There’s nothing final. It’s an idea. We share our patterns and design instructions online, and you can make it your own. Are the people that make a hoodie with our instructions stealing? No! They’re appropriating, of course, but they’re also owning it. We’re building a community by getting rid of ownership.

CKE: Your brand name refers to something that’s unfinished, but when do you decide that a collection is finished? Is it according to the industry’s schedule?

LB: Yes, it’s based on dates. You have the industry that tells you when to show, when to produce, when to deliver. There’s not much of a freedom. As a creative, you can work on a thing forever. You can always improve it, always evolve, make it more efficient and better. But it’s also just clothing, right? At the end of the day, we’re just making clothes. We’re not saving lives; we’re not operating on an open heart.

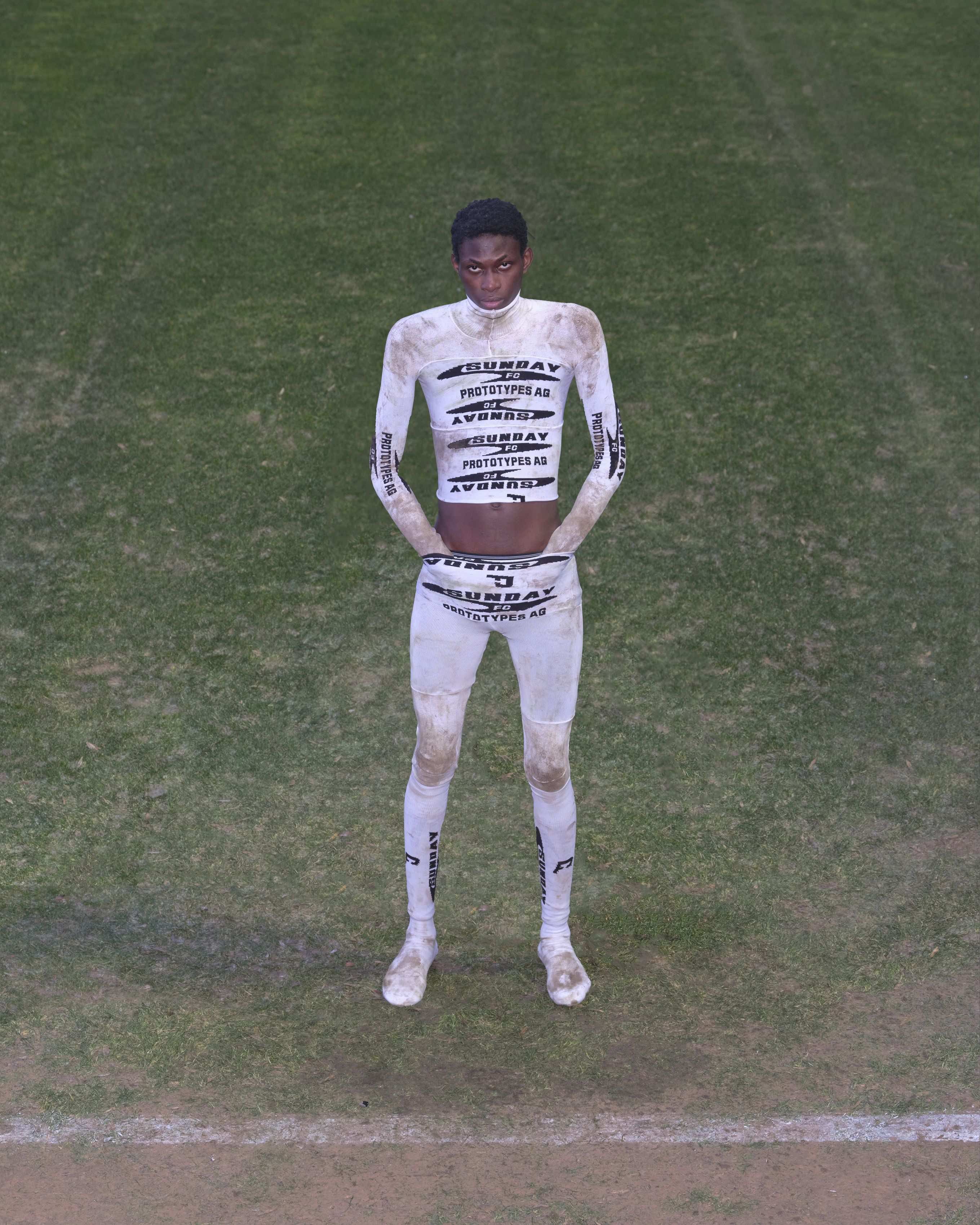

CKE: Your current collection is an ode to football, a historically unifying sport for the working class in Britain, which is now being gentrified. Why is this interesting for you?

CALLUM PIDGEON: That mainly comes from me, growing up in a small town in England, where football has this whole community built around it. And it just felt right to interpret it in our own way. Football has always been in our repertoire of research. Last year, we were traveling a lot, and it felt right to go back home.

LB: It’s a love letter you wrote to football and to the society around it.

CP: I actually shot it at my local football club where I used to play as a kid, which was super sweet. The staff at the club let us have the pitch, the changing rooms, and the bar. It was chill.

LB: And, as a thank you from our side, we sponsored a new kit for the women’s football team. So, they’re going to play in Prototypes. Football is such a uniting sport because you don’t need much money for it. You just need a ball, and that’s it. Prototypes has always been inspired by codes of society, such as uniforms. And football clothing is a uniform, in the same way as military garments or workwear.

CKE: Given that this is something you actually grew up with, Callum, it’s certainly not a form of appropriation. But given that you’re now part of a different context, would you accept critique from someone who claims that you’re appropriating a working class “aesthetic”?

CP: I’m glad that question was in there, actually. I know I shouldn’t read Instagram comments, but sometimes I do, and I get a bit wound up by people thinking that we’re appropriating working class culture, which is what I grew up with. It’s important to make it personal, that’s my background. It doesn’t have anything to do with gentrifying. It’s honest and paying homage.

Fashion is surely an exclusive industry, but I think you can open it up. That’s what we’re doing with the free downloads of patterns and guides on our site. The stencil that we put on Instagram turned into loads of people just stenciling in the graphics themselves, that’s progressive in my opinion.

LB: Of course, you can buy this hoodie produced by us or produced by the industry for us. But you can also just download the design and make it yourself. It’s important to offer alternatives that are accessible for everyone. Therefore, we offer prototype designs and prints to download for free.

In terms of price point and accessibility, it’s super important to highlight that there is an issue within the industry and with how it’s producing. For us, making a freshly produced pair of denim would be a third of our making costs in comparison to asking people to upcycle.

CP: A lot of factories love the traditional way of doing things, which is cutting a pattern from a roll of fabric. So, we have to find a factory and people to work with that enjoy the process of cutting things up and putting them back together. It’s more time consuming. The labor that goes into these pieces comes with the price. Unfortunately, we’re not currently in a position to bring the price down for everyone. But I think it will happen when up cycling becomes more normalized in the industry.

LB: There needs to be more awareness, like we have for food now. I think that people in general have a better understanding or awareness around food and meat. This knowledge hasn’t really been applied to the fashion industry yet. A lot of people will say about vegan leather, “Ah, it’s amazing.” Well, no, it’s actually an absolute fraud. It’s coated cotton. It will literally never leave the earth. Is that really the future? No.

CKE: You’re now based in Switzerland. According to the 2023 Global Wealth Report, Switzerland is the top country when it comes to the mean average wealth per adult, which is at almost 700,000 dollars. This is not distributed equally of course, and I feel like conversations about Switzerland often forget that there also exists a working class.

LB: First of all, neither of us is from Switzerland [laughs].

CP: I’m from the UK and Laura is from Germany. But we came to Switzerland when Vetements changed their office from Paris to Zurich.

LB: We had just left Vetements, and the pandemic started. We were in Switzerland and not working as a lawyer or doctor, but working in a creative industry, which is not really present here. So, it’s a fair question you’re asking. The working class in Germany, for example, looks very different.

It’s difficult to build a clothing brand here, but it’s possible. It’s quiet, it allows us to get on with things without too many distractions.

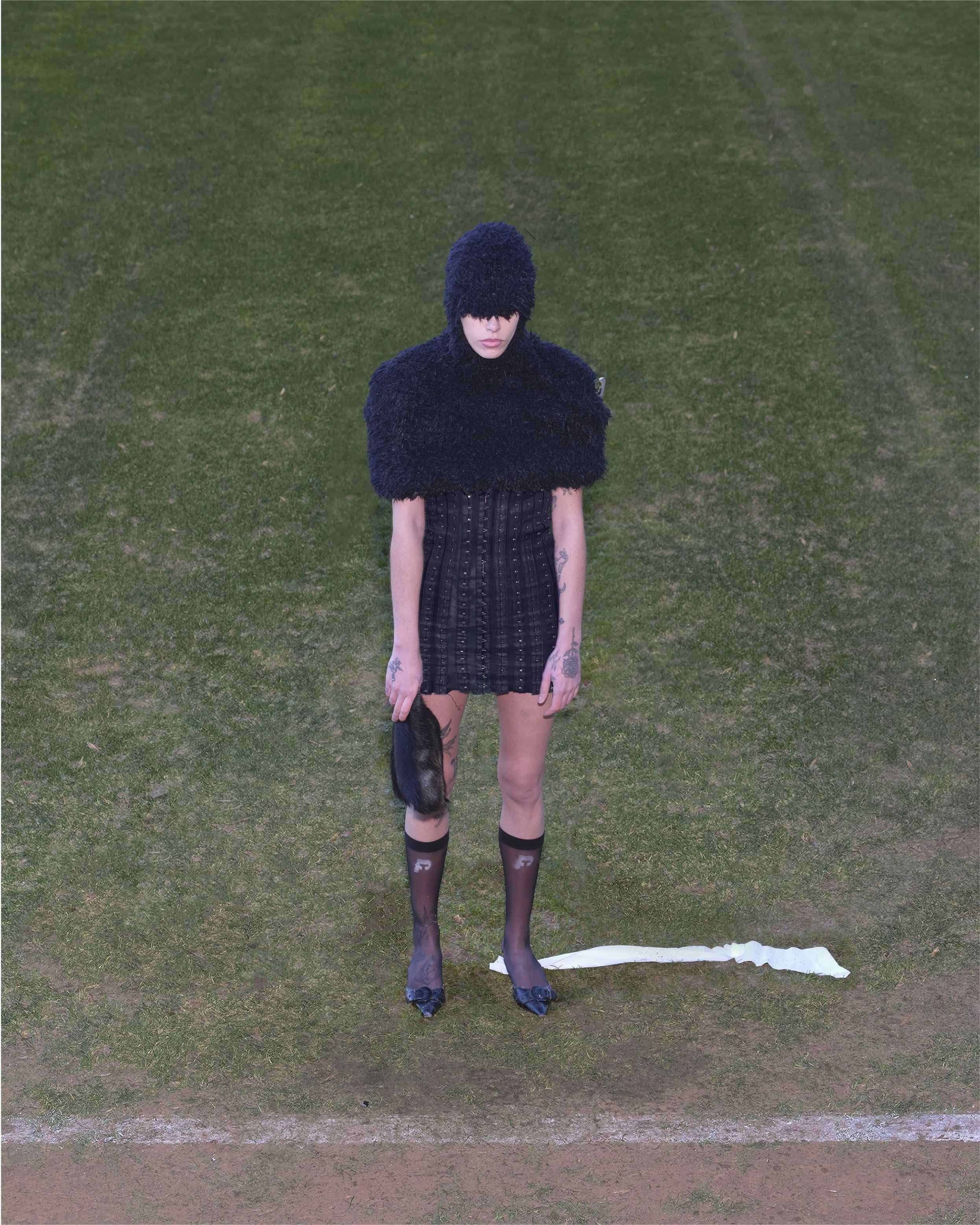

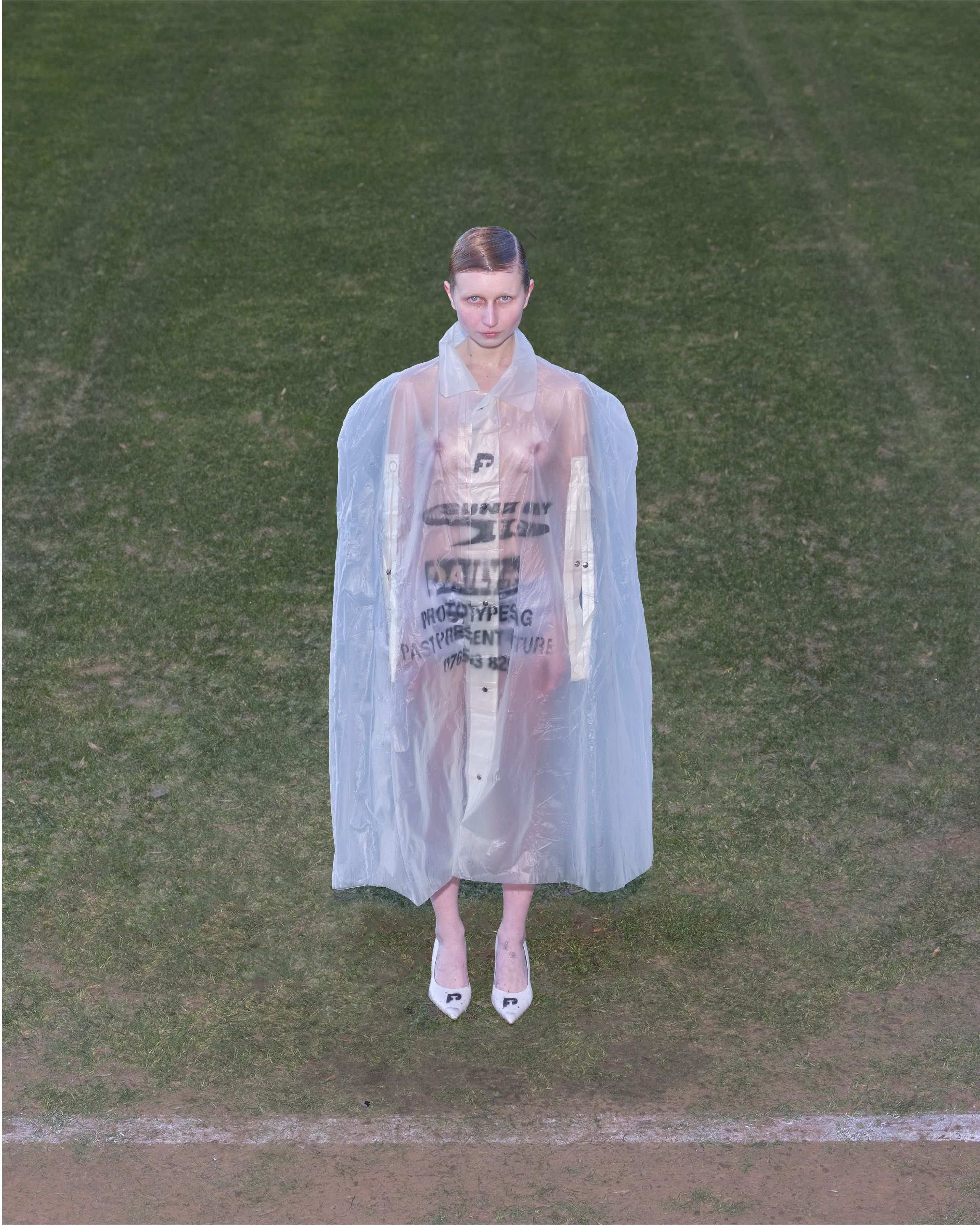

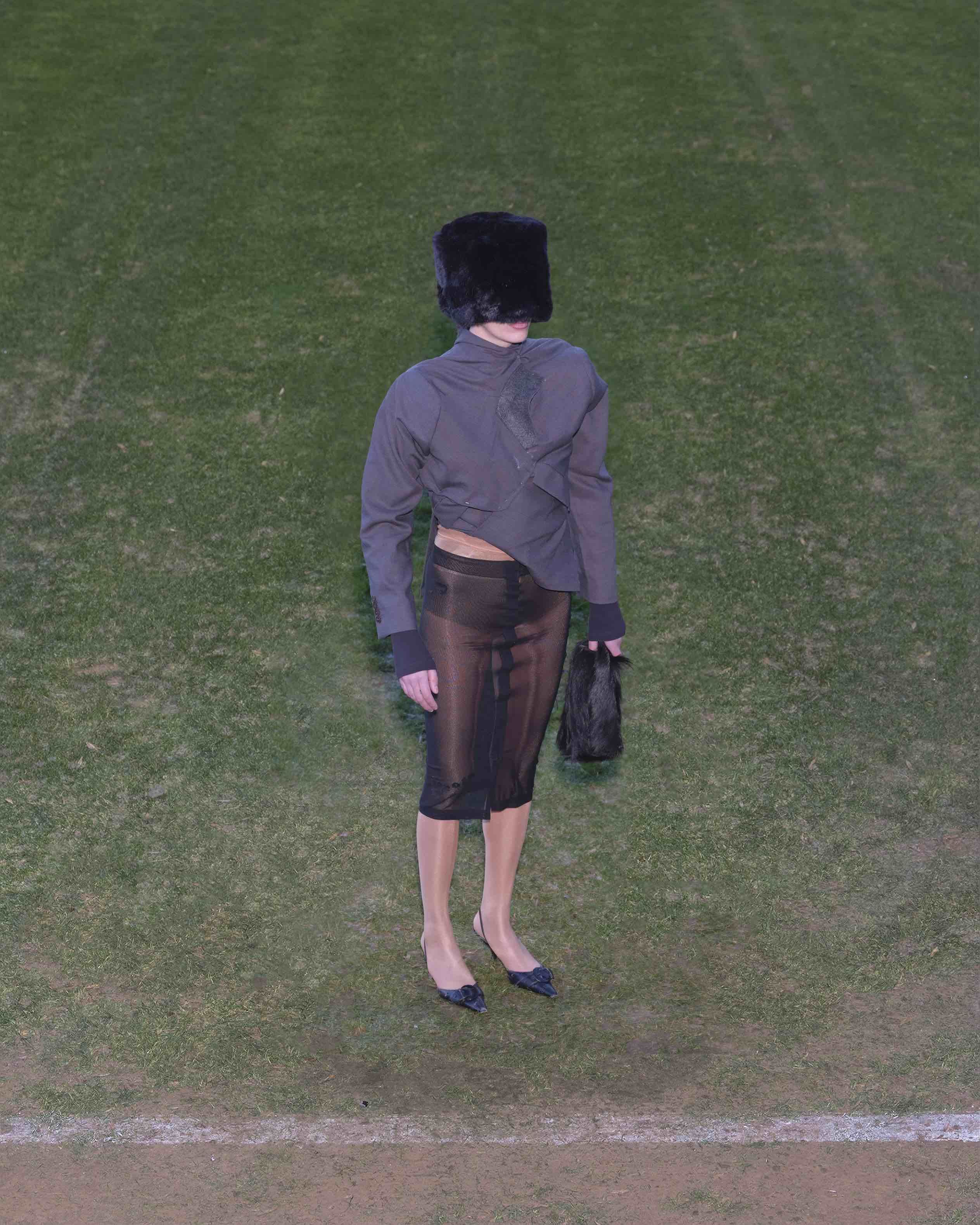

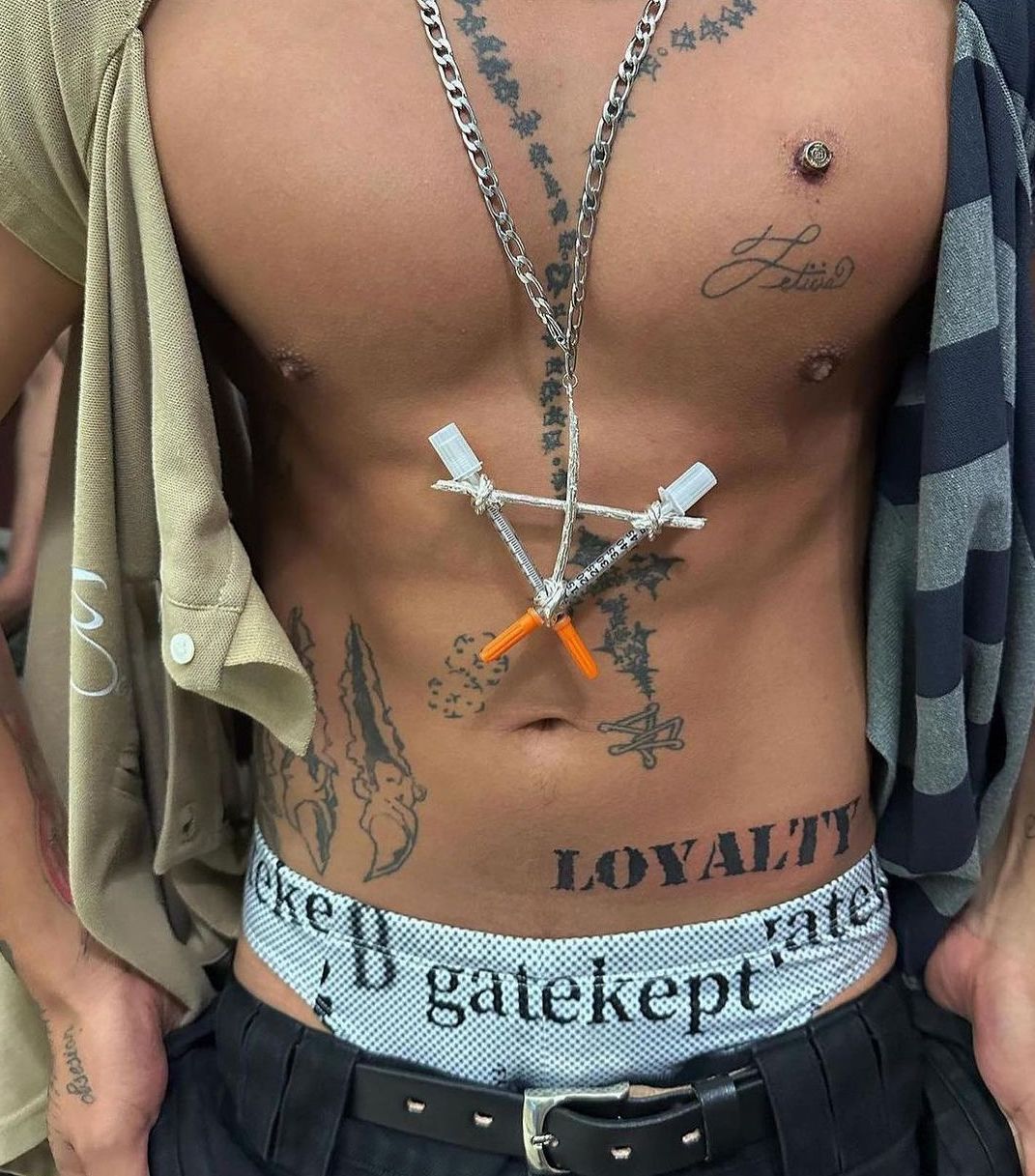

Lookbook

Credits

- Text: CLAIRE KORON ELAT

- Design & Creative Direction: LAURA BEHAM

- Design & Creative Direction: CALLUM PIDGEON

- Photography: RAPHAEL BLISS

- Fashion: BETSY JOHNSON

- Hair: CHARLIE MINDU

- Makeup: STEPHANIE KUNZ

- Casting: CONAN LAURENDOT

- Producer: NATHANIEL SOUSSANA

- Producer: BEBE PIDGEON

- Design Assistant: RENATO DE SIMONE

- Design Assistant: ELIAH MAAG

- Fashion Assistant: MORGAN VAN GOETHEM

- Hair First Assistant: NIRINA METZ

- Hair Assistant: ALASTAIR JUBBS

- Hair Assistant: JAMIE KEEGAN

- Makeup Assistant: LIZZIE CHECKLEY

- Casting Assistant: ISSA ROMAY

- Production Assistant: BLANCHE ROLLET

Related Content

“Stay Commercial”: BETSY JOHNSON’s PRODUCTS

Blackhaine: Harsh Realities

MARTINE ROSE in Three Acts

DEMNA GVASALIA on Vetements, Balenciaga, and THE SYSTEM

Menswear Metaphysics: GRACE WALES BONNER’s Bejeweled Visions

Barragán for Dummies

Vetements Stylist LOTTA VOLKOVA: “WE NEED THE SYSTEM”

Do We Want Anarchy Or Guerilla Warfare? Julian Klincewicz & RASSVET