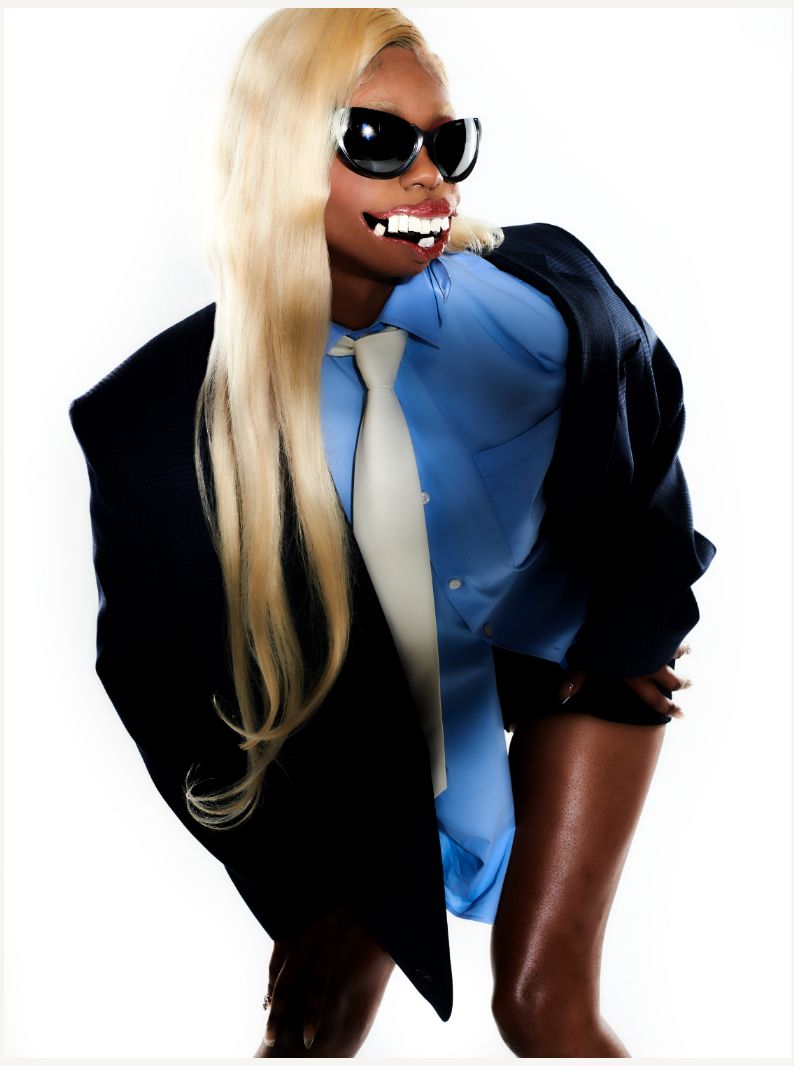

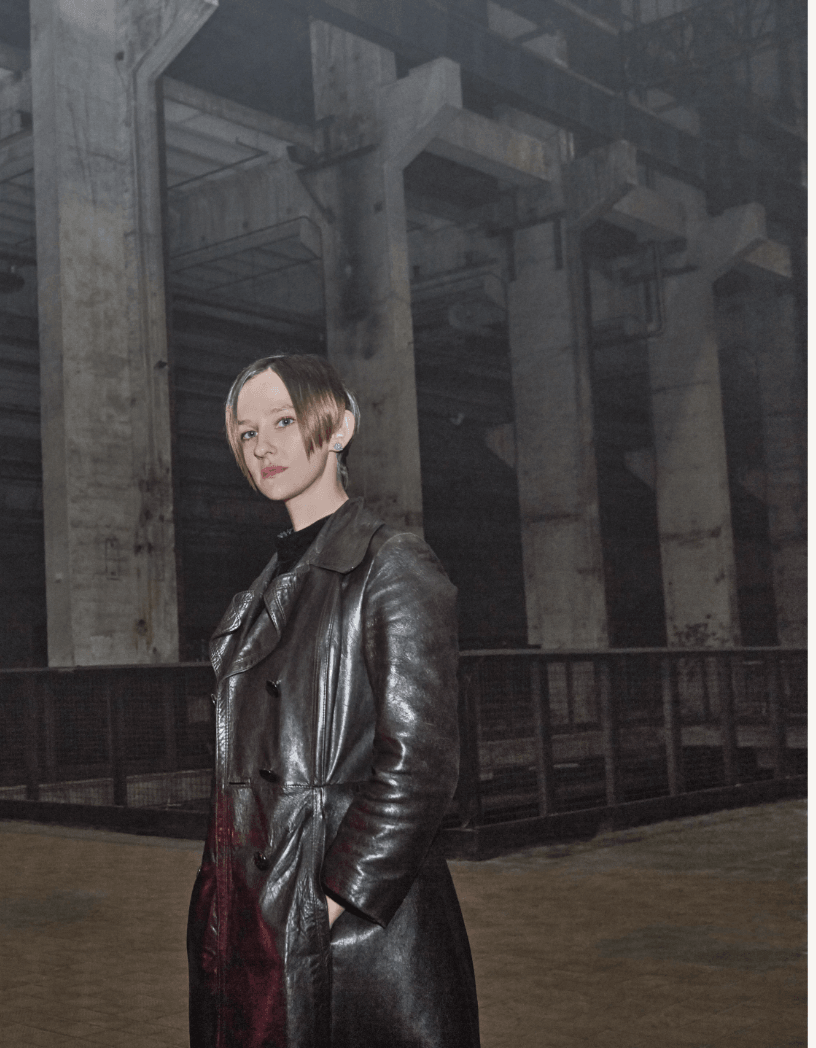

NADIA LEE COHEN’s Conveyor Belts and Stylized Realities

|ALMA LEANDRA

Two muscular women with three breasts and leathery tans appear frozen, as though their blood has been substituted with wax. Elsewhere, a set of twins with beehive hairdos, are holding beach gear—towel, tanning lotions, and a popsicle—in their four hands. Whether their identical faces are filled with boredom, disapproval, or confusion remains ambiguous.

For her photos, British artist, photographer, filmmaker, and model Nadia Lee Cohen creates characters of her subjects before making portraits of them. This is done through an arduous study of the people she encounters, whom she then fictionalizes.

Her book Women was conceived in secret over the course of six years—while Cohen was shooting and directing for the likes of Balenciaga, Gucci. Saint Laurent ans A$AP Rocky and modeling for Schiaparelli—and it depicts over 100 women in highly stylized settings. Then, in her famed book of self-portraits, HELLO, My Name Is, she herself morphs into 33 different personas of varying genders, size, and age, and explores the complexities of American stereotypes. In 2022, photos from both books alongside plastic human-sized sculptures and a dry cleaner’s garment conveyor were shown at Jeffrey Deitch, Los Angeles, marking her first major solo exhibition in the United States.

ALMA LEANDRA: There are no images of you holding a camera on the internet. Why?

NADIA LEE COHEN: Are there really none? Me holding a camera is probably not the sort of photo I would orchestrate. There might be one of me on the Daily Mail shooting Kim (Kardashian). I think it’s quite low-res. I have no clue who took it.

AL: What often goes unnoticed in this industry are things such as the weight of a camera. As a woman with a lower muscle percentage, it can be demanding to handle the bulk of a heavy camera.

NLC: This is so true. I think about it when I get home and feel really achy but never really speak about it. My camera’s very weighty, and I can feel it all over my body after a shoot. Maybe this means I can start expensing massages? I can’t really complain about this though, because I don’t take photos all that often. I’m more of a sporadic shooter. Who we should really feel sorry for are steadicam operators. They have to strap on 100 pounds of gear and glide like a ballerina through a room. That’s something to complain about, especially if they’re filming in the desert or something.

AL: How do the two realms of being behind and in front a camera coincide?

NLC: I think I feel empathetic towards whoever is in front of the camera, and way more sensitive to what they might be feeling.

AL: Your self-portraits still emulate authenticity although they’re set in a very staged manner. Are the characters inspired by people you know?

NLC: The way they look is based on real people, but not just one person, if that makes sense. It’s like a hybrid of people I’ve encountered in daily life, in a film or even a family member. They absorb a little fraction of each of those people which then makes them their own unique person. That’s sort of how we construct our identities anyway. Our personality and the way we choose to look is fragments of everything we’ve ever encountered, read, or watched. We’re all like Frankensteins.

AL: Is this authenticity something that you focus on?

NLC: It’s not really something I'm conscious of, but I can say that I’m not really drawn to anything “fantastical” in the art I appreciate. My visual inspirations are usually documentary, but it’s normally staged documentary. People like Martin Parr or Larry Sultan, where everything appears as a heightened reality.

AL: The characters you depict often embody stereotypes associated with specific personality types.

NLC: I’m drawn to a pretty consistent type of person, I'm not sure why that is. But, for instance, I’d probably never shoot a steampunk.

AL: Cindy Sherman’s self-portraits were the result of desiring self-transformation; is it the same for you?

NLC: It’s more about character study, similarly to how you might think up a character for a film. Collecting their belongings was actually the most enjoyable aspect of that project. I spent months looking out for things that I felt could directly relate to that person, and the more objects I gathered the more sense it made who they belonged to and the more real that character became.

AL: Did you feel like you were in the body of someone else?

NLC: Well, yes because I was. But not in a pretentious method acting way. Just in a physical, playing dress up kind of way.

AL: What has been the most enjoyable character to dress up as?

NLC: I dressed up as the late Lolo Ferrari last Halloween. She is a French actress who shot to fame for her F-sized breasts. I had a pair in my garage left over from a project and my prosthetics artist told me they were going to go rotten if we didn’t use them, so I put them on, went out, and had one of the best nights of my life. I really didn’t want to take them off.

AL: Do you still put them on secretly?

NLC: You can’t! You can only use them once. They’re glued on and a nightmare to remove. I was up until the early hours in knickers and a wig cap, trying to get them off. That’s the problem with prosthetics on Halloween. You can’t just pop them on and off.

AL: You spent your formative years in Essex. What was your upbringing like?

NLC: I grew up on a farm in the countryside. I spent most of my childhood in muddy wellies with unbrushed hair. I hardly remember looking at my reflection. When I started at secondary school, I was wearing a long- pleated skirt, clumpy shoes, and two Princess Leia buns. As soon as I got to the school gate, I realized it was the wrong dress code as a gaggle of bleached, tanned, designer mums and daughters stepped out of Audi A3s and BMW convertibles in their early 2000s mules. I’d never seen anyone that looked like that before and I was fascinated. I think those women were my first character studies.

AL: What aspects of the Essex are you now seeking in America?

NLC: It’s impossible to emulate anything British in LA. The closest I can get is tuning in digitally to Radio 4 and eating the crumpets that I've smuggled back into the country. Oh wait, you're talking about characters! Ok then, the Essex women I described earlier are definitely at the heart of a lot of my character inspirations, but not all, it’s just one of the many looks I’m drawn towards.

AL: How do you find your characters?

NLC: Los Angeles is the best place for character casting. There’s a hunger to work, and the people there seem more open to trying things as opposed to casting in Paris or London where the people seem more suspicious and reluctant towards projects.

AL: You play a lot with childhood themes and bright colors—almost like trauma therapy.

NLC: I wonder if I am traumatized. I watched a lot of cartoons as a kid. Ren and Stimpy is pretty traumatic. The art and film I’m interested in usually has a really considered color palette. And I probably learned subconsciously from looking at that stuff about what colors go together. But in trauma therapy, color can make you untraumatized, right?

AL: It can act as a catalyst to uncover the fundamental origins of traumas. Referencing the music video you did for A$AP Rocky—you embed these cartoon characters, and theoretically it all looks upbeat and child-friendly but if you look closely, there is something eerie about it. It’s this juxtaposition or at least stark contrast between the two.

NLC: I’ve thought about this contrast. Where I grew up a primary color palette didn’t exist. Being raised amongst tranquil beauty and a color palette dominated by greens and browns made anything opposite feel new, exciting, and inspiring. LA is a dichotomy in itself. It’s ugly, it’s boring, it’s beautiful, it’s fun, lonely, social, rich, and poor, etc. And I’m in this constant state of confusion about whether it was the correct decision to call my home. So, I leave all the time. To be able to experience those opposites day to day is confusing, and it’s unsettling, but I think that is the theme. I think that I feel more anxious when I’m in normalcy and comfort, so I travel a lot to escape that. But something always draws me back to that discomfort.

AL: Your fascination with striking lifestyle contrasts, evident in both your artistic expression and personal experiences—shifting from a rural farm existence to the refined urban life of LA—suggests that you are drawn to extreme opposites.

NLC: Someone asked me this the other day. I’m drawn to violent cinema yet I'm extremely squeamish. I love chaos but also organization. There’s a ton of those sort of contradictions within me —It would take me ages to think of them all!

AL: Your art deals heavily with the USA and stereotypes. Why does this fascinate you?

NLC: I was on a plane the other day and the man sitting next to me was watching normal US telly and I was watching UK telly. The US telly was all shouting, adverts, bright colors, buy, buy, buy, lots of text, it was manic. The UK one was quiet and still and slow. I thought to myself, this is the difference right here. I’m watching his telly, even though I should be watching mine.

AL: There’s also a sense of social criticism in your work. The way people are portrayed seems almost like criticism of the viewer—that they would classify this person immediately. For example, classification of white trash.

NLC: Right. It involves a judgment we’re not supposed to make, but we naturally do. We’re captivated by narratives like this, especially within the media. There’s a recent case in the UK where Lucy Letby, a plain Jane, a sweet looking nurse had been injecting air into the blood and stomachs of newborns, overfeeding them with milk and poisoning them with insulin. This is even more awful and newsworthy because she doesn’t look like a monster.

AL: Humans compartmentalize. It’s the fastest way for us to understand something. What I find interesting is how your approach questions that tendency. Going back to the A$AP Rocky music video—how much of this element of mockery did you want to involve? I’m referring to the pig cops.

NLC: It depends on what the project is. That’s not always the intention, but in that case it was. I don’t think you’d believe me if I told you it was an accident.

Credits

- Text: ALMA LEANDRA

Related Content

“Stay Commercial”: BETSY JOHNSON’s PRODUCTS

Coastal Convictions Are Fallible

A Martine Rose Slip: JORDAN/MARTIN HELL

Reality TV as a Sociological Analysis: JAMES BANTONE

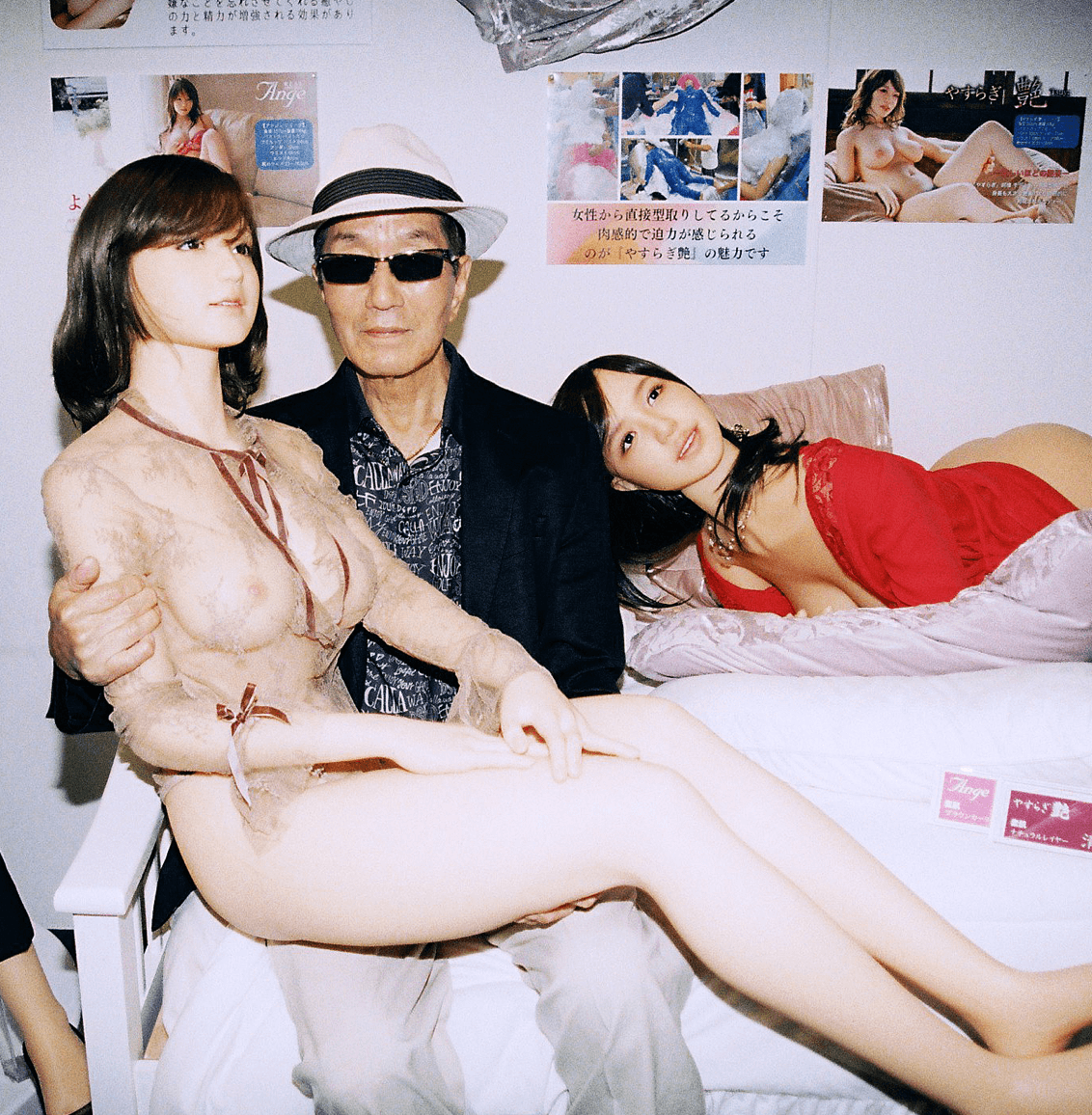

Fetish Nights in Tokyo: JOSHUA GORDON

What’s Your Religion? Dior Tears

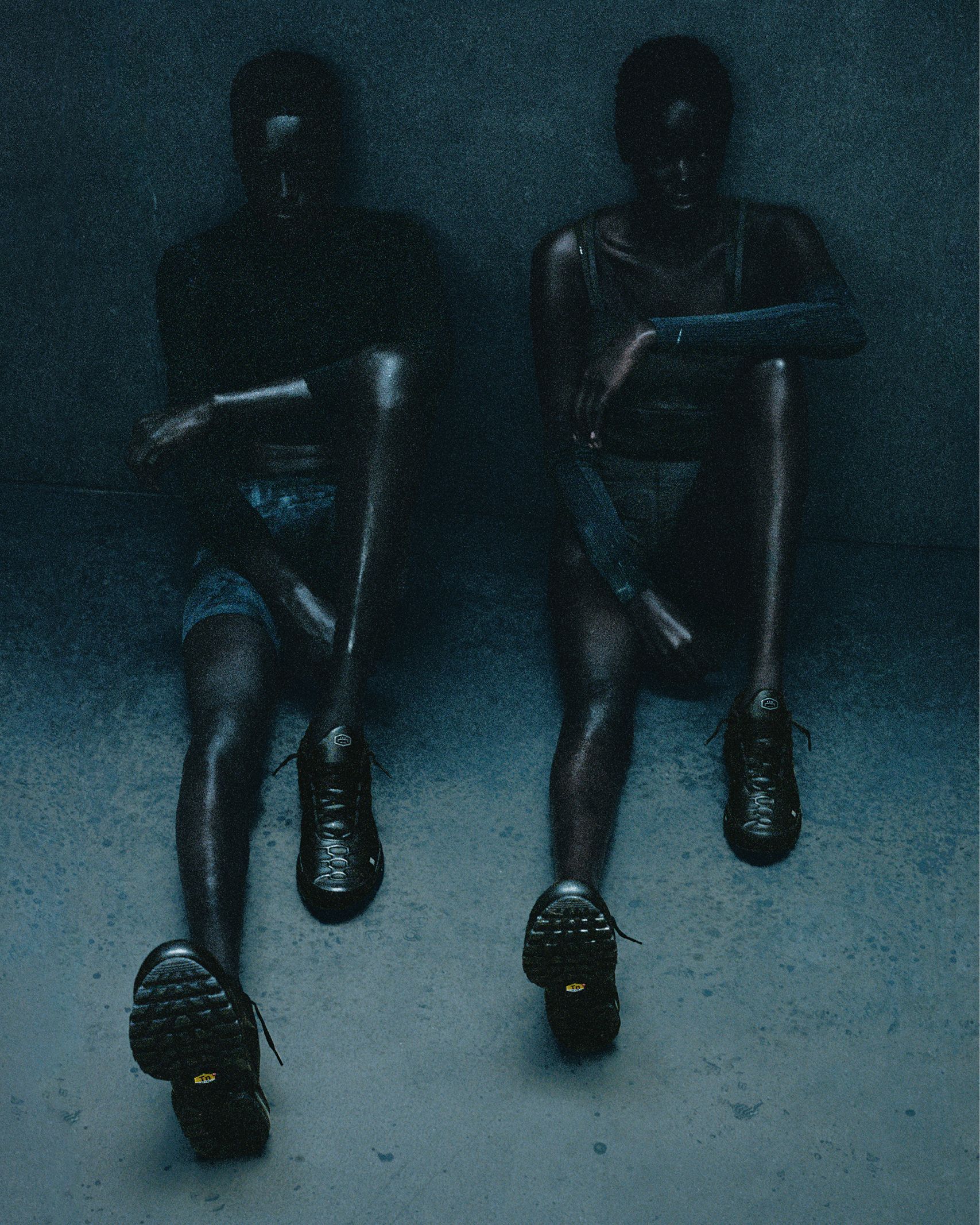

Never Growing Up: GABRIEL MOSES and SAMUEL ROSS’ ACW_NIKE TN98

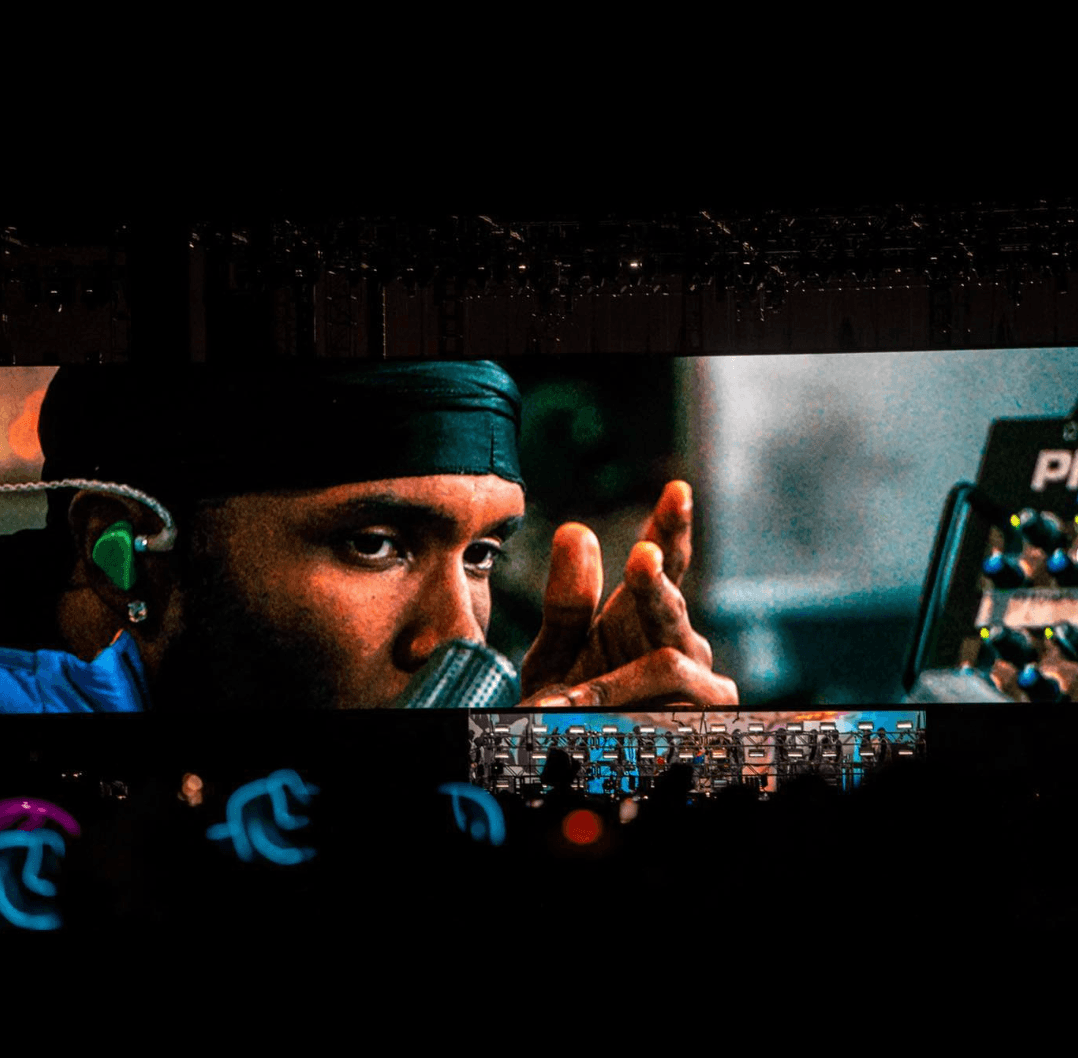

FRANK OCEAN: the Mysterious Artist

CATERINA BARBIERI’s Landscape Listens