METAHAVEN: Somewhere Near You, Soon

|ROBERT WIESENBERGER

METAHAVEN is a graphic design studio based in Amsterdam. Run jointly by Daniel van der Velden and Vinca Kruk, it produces graphic identities and installations alongside books, essays, lectures, and films. Metahaven’s visual research explores networks, geopolitics, and transparency. Commenting on its work in a post-Snowden era, and in anticipation of their forthcoming book, Metahaven discusses the stakes for design and life at a moment when reality reads increasingly as science fiction.

Marshall McLuhan’s four-page essay “The Invisible Environment: The Future of an Erosion” appeared in the 1967 issue of Perspecta, Yale’s graduate journal of architecture. Every age is defined by its media, he wrote, which create an environment so total and saturating that it’s invisible to its contemporaries and only becomes recognizable as it draws to a close. The dawning “electric age,” McLuhan believed, was doubly invisible for also being decentralized and immaterial. Yet art could visualize the present through what he termed “counter-environments.” He hastened to add: “If the environment or process of change gets going at a clip consistent with electronic information movement, it becomes very easy to perceive social patterns for the first time in human history.”

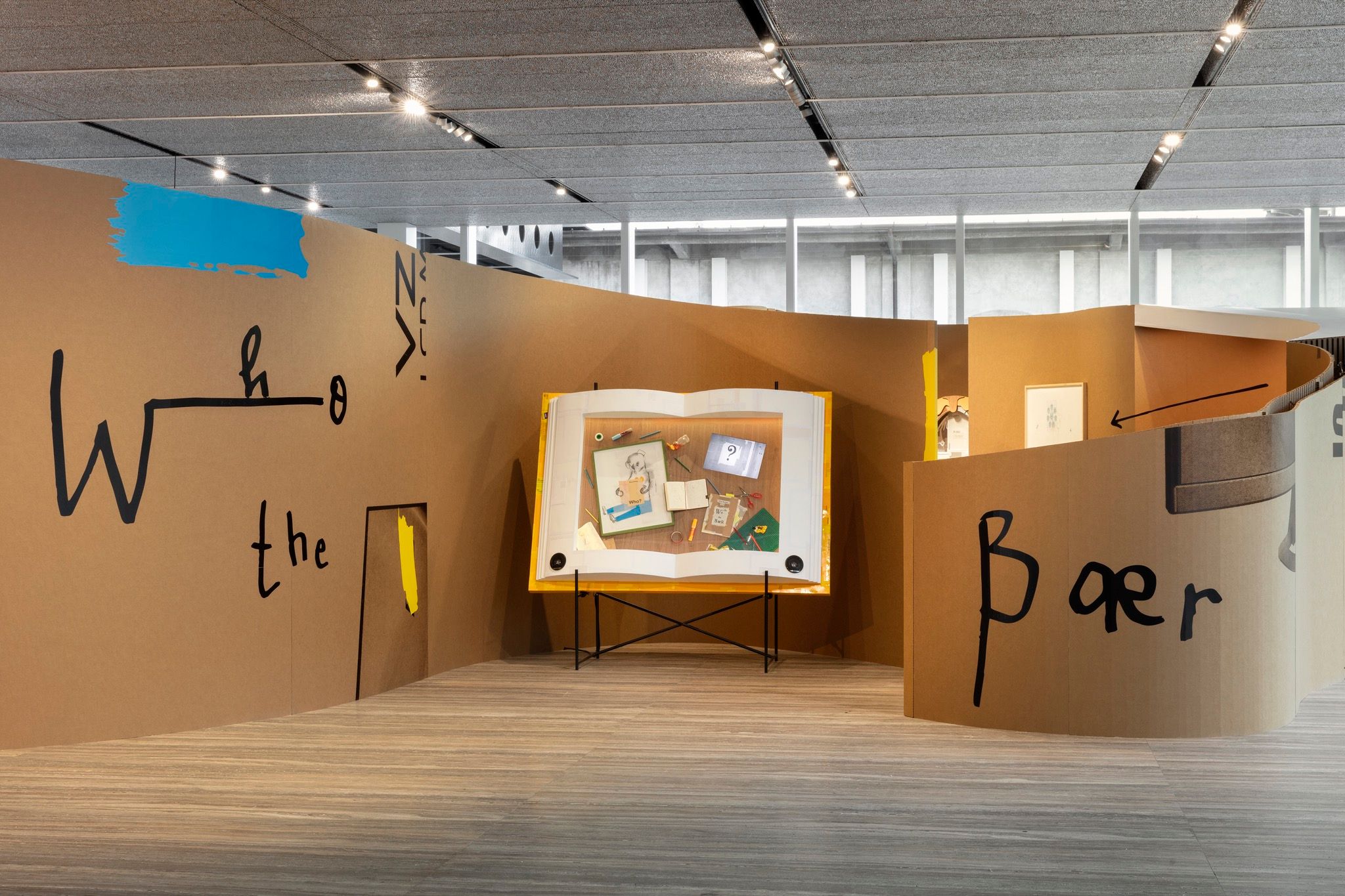

Metahaven is in the business of making counter-environments. Its research subjects have included Google and the Principality of Sealand, and it has partnered with organizations like WikiLeaks and Independent Diplomat. In a speculative role, it has created entities like Facestate® and Stadtstaat – chimerical bodies politic-corporate that look less and less fanciful in a time of simultaneous deregulation, privatization, and pandemic “network fever.” The studio’s more traditional clients include arts organizations, NGOs, and publishers.

If McLuhan anticipated the decentralization of the digital age (packet switching, an Internet precursor, arrived in 1969, and the personal computing revolution was yet to come), then Metahaven’s work may signal its end. The anarchic utopianism of the Internet, which we assume to be its essence, may have been just a brief phase in its development, if it ever truly existed at all. Metahaven grounds the cloud, pinpointing where its physical infrastructure touches down on a map defined less by state borders than by a few supranational jurisdictions.

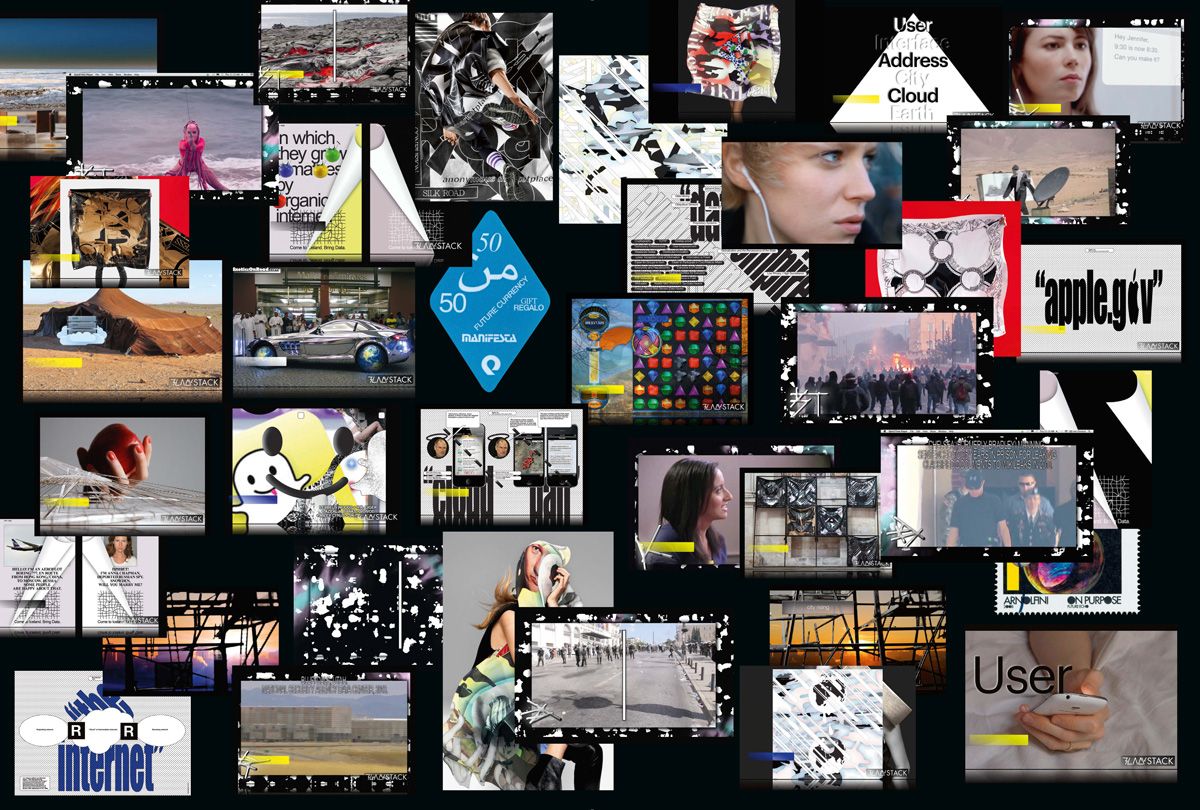

A tic-tac-toe board reading “L.O.L” down and “S.O.S” across maps the present, absurd moment and the coordinates of Metahaven’s practice; in Slavoj Žižek’s words, quoted by the studio in a recent installation, “The situation is catastrophic but not serious.” Metahaven’s work tends to run along both these axes at the same time. And its practice in various media slides on a durational scale from pithy Tweets and captioned, viral-ready JPGs to exhibitions, slide presentations, e-books, videograms, serial policy research papers, and a 600-page book.

Daniel van der Velden teaches at the Sandberg Institute in Amsterdam and at Yale University in New Haven. Vinca Kruk teaches at ArtEZ Institute of the Arts in Arnhem. They joined in 2004 to create a visual identity for the Principality of Sealand, a World War II-era anti-aircraft tower in the North Sea turned mini-state turned data haven turned ruin. Their first book, Uncorporate Identity (Lars Müller 2010), combines this with other speculative projects, commissioned essays on design and geopolitics, and web-based visual research in a dense and multi-layered volume. It is, as one review noted, “a design monograph that one is actually meant to read.”

Also in 2010, Metahaven partnered with WikiLeaks to reconsider its visual identity and give them a face that was not Julian Assange’s. It soon became clear, after Visa, MasterCard, and PayPal stopped processing WikiLeaks’s payments, that what Assange’s organization really needed was revenue.

As if creating merch for a band, and with all proceeds going to WikiLeaks, Metahaven made t-shirts and mugs commemorating major disclosures, which were then listed like tour dates, e.g., “Collateral Murder: July 12, 2007 / Released April 5, 2010.” Further examining notions of concealment and revelation, they also produced a series of silk scarves called Transparent Camouflage.

“Captives of the Cloud,” an ongoing series of essays written for e-flux journal, combines the format of an amplyfootnoted policy paper with cartoonish, infographic-style illustrations diagramming the architecture of the Internet and its geopolitical lines of force. The first installment, published in September 2012, addressed America’s super-jurisdiction by way of laws like the Patriot Act, which can be enforced in other countries thanks to U.S. ownership of the major social media cloud companies and the far-flung locations of their servers and network connections. Irrespective of its “hard power” (military might) or “soft power” (likeability and influence), American “network power” (control of the products, services, protocols, and infrastructure of the Internet) is considerable.

Nine months after the first essay, Edward Snowden’s leaks appeared, revealing the NSA’s front-door access to the cloud through its PRISM program and, four months after that, its back-door access via the so-called MUSCULAR program. A leaked NSA PowerPoint slide showed two cartoon clouds representing Google and the public Internet, with an arrow drawn to their Achillean server connection. The giddy legend reads, “SSL added and removed here!” Below, the anonymous author has scrawled a smiley face. The picture could just as well have been pulled from one of Metahaven’s essays.

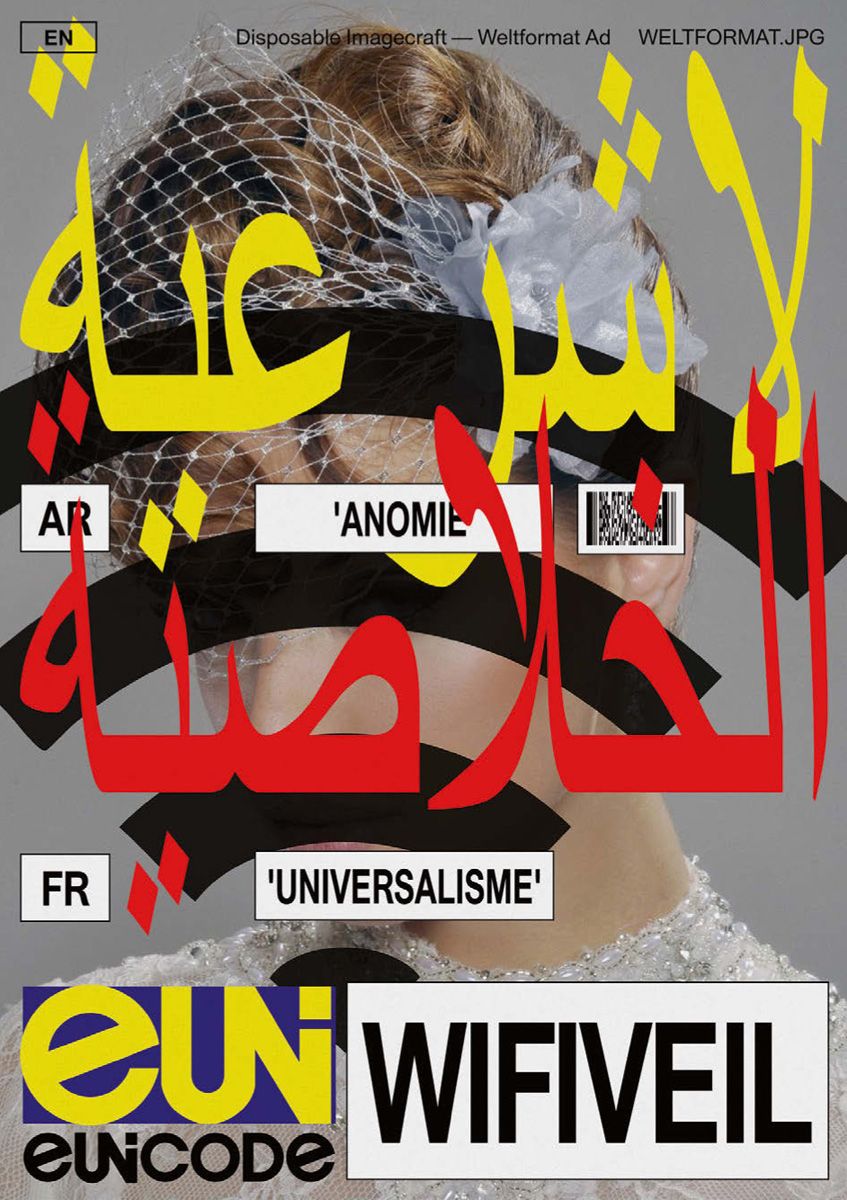

The subversive force of images, and the new ease of making and circulating them, is the subject of Metahaven’s recent e-book, Can Jokes Bring Down Governments? (Strelka Press 2013). While the studio is conversant in the language of policy research, it also dabbles in the dadaistic, promoting the meme as an effective anti-discourse against power. As they argue, viral polemics constitute a new action for graphic design analogous to the political posters of the 1960s, enabled by social media on one hand and a collapsing labor market on the other.

Conditions of visibility – of opaque governments and transparent private lives – animate Metahaven’s most recent work. From the cloud down to people, these projects deal with the national security state, the consequences of austerity in Europe, and the variously alienating and emancipatory effects of our hypermediated moment. Two of its most recent projects are films: a 14-minute videogram called Black Transparency and a forthcoming one called City Rising. Just as currency or postage stamps were prestige assignments for graphic designers of yore (and Metahaven has designed speculative coinage and postage stamps for Sealand and others), these two films suggest new, immaterial currencies that thwart the laws of economic scarcity by being inexhaustible and fill the vacuum left by collapsed public services. In Black Transparency, the currency is secrets; in City Rising, it is generosity, reciprocity, and love.

Black Transparency: The Right to Know in the Age of Mass Surveillance (Sternberg 2014) is the title of Metahaven’s most recent book, a compact collection of design and research addressed to the anti-regime of involuntary transparency inaugurated by WikiLeaks and its ilk. We discussed the studio’s recent work, a combination of critique and advocacy that both visualizes the present alongside organizations that might not otherwise seek out graphic designers and creates new pockets of reality – or havens – within it.

What is “black transparency”?

“Black transparency” is a disclosure of secrets that is itself secretive. Retrieving secrets from behind whatever firewall or server, a process that is in the service of openness and the public, is secret. That’s a paradox inherent to the term black transparency. And it acquires other overtones – black metal, black markets, black knight. When we started to look at WikiLeaks and work with them it was very enigmatic what they were doing, but it was in the service of something very open. We were looking for a term that would describe that.

What’s new about black transparency?

Black transparency mobilizes people inside organizations to cross the boundaries of these organizations. That’s something that WikiLeaks pioneered. WikiLeaks is often seen as a straight continuation of Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers tradition. And in its political spirit, it may be so, but in the way it operates, it’s very different. Ellsberg was a seasoned RAND Corporation guy, and what he did was substantial in regard to the organization he worked for for many years. Yet someone like Chelsea Manning had not worked for the military for that long before she began leaking secret files. The same goes for Edward Snowden even more so. He was a temporary contractor for the NSA, which tells you about the kind of flexible, immaterial, temporary labor reshuffling in that world. It also means that loyalty and belonging to an organization – and, hence, the walls around an organization – are changing, and black transparency is running on that.

What valences does transparency have for the design of geopolitics?

Colin Rowe and Robert Slutsky wrote their famous essay in which they talked about literal and metaphorical transparency. Metaphorical transparency is difficult to attain, and their example was Le Corbusier’s plan for the Palace of the League of Nations in Geneva. It’s interesting that they talked about this in relation to an institution, and of course the League of Nations was a product of thinking about diplomacy as a transparent procedure. It was an invention of Woodrow Wilson, who believed that all procedures of public relevance should become transparent.

Julian Assange became obsessed with his own secrecy, and with that of his organization, while calling for transparency all around him. If black transparency is the present state, do you see it as transitional to a viable norm of transparency-transparency?

There are a lot of books that promise this great future that we’re entering, when everything will be transparent, and there will be no more secrets. That’s really not true. We’re not going to have a world where there are no secrets. So the fact that black transparency doesn’t predict the end point where we’re going but talks a little about where we are now – and how that’s come about – is actually the modesty of the proposition.

The WikiLeaks dropbox used to be its most well-protected, holiest of holy – the inner sanctum, where the leaker anonymously dropped the file. Then [former WikiLeaks spokesperson Daniel] Domscheit-Berg and “The Architect” left WikiLeaks, disabled the dropbox, and started their own, OpenLeaks, and nothing came out of that.

Now, the Freedom of the Press Foundation, which is also a funding organization for whistle blowing platforms, has released an open-source dropbox that anyone can use. What used to be proprietary to a singular brand is now something everyone can use. So that’s a more democratic use of the means of production of transparency. Rather than saying that we’re going to a model where transparency will be arranged for, it will probably become more democratic, and perhaps more accepted.

How will Black Transparency: The Right to Know in the Age of Mass Surveillance (2014) differ from your last major book, Uncorporate Identity (2010)?

In many ways. It will be a lot smaller – it won’t be 600 pages printed in five colors. It will be a pocket-book, something you could read on the train. The book will consist only of text by us. So it’s not a reader. Uncorporate Identity took the idea of making a compilation of the most interesting writings on design and geopolitics at that moment as we could imagine it, in part commissioning them. This is much more a book of our own writing, where quotes are included.

Metahaven’s work ranges in duration from captioned JPGs to serial essays. You’ve also written (in Can Jokes Bring Down Governments?) about the economy of attention in which memes compete. How do you think about attention in your practice?

Since we’re on social media, we are more keen about the combination of what we do and how it’s viewed. One of our first projects was to release a poster for WikiLeaks on behalf of a country every day for 196 days. That was a series of actions that used social media as a context. The idea that there’s someone else who’s reacting to what you do has become more important to us. We have made a few memes, but we don’t aim to be some kind of meme studio. We assume that you can produce long texts, post on Twitter, and at the same time work on research that often takes months or years to develop. Those things co-existing is really important in our practice.

Black Transparency is also the title of a film you have just released. You identify as graphic designers, though two of your most recent projects are films. Why film?

Black Transparency was originally planned to be a documentary – a lot of the material we had found in researching WikiLeaks was video, and we somehow couldn’t give it a place in any of the other work. Making a documentary seemed like a logical next step, but in the end, the film became something else. Moving from print to film is a big step, but it’s also quite natural in the sense that our work is so layered, and so charged with different narratives, with different references, that film is a really great way to explore our visual language.

In terms of format, what do you call these films?

We call them different things. We called them videograms to start with – graphic design with moving pixels. Black Transparency was a videogram. I think it is still more graphic design than film. There is also an overlap between graphic design and video that is really relevant, in that graphic design is being liberated from the print object, from the static.

The film Black Transparency begins with a blinking cursor and the narrator saying (over the theme from The Matrix), “We have nothing left but our vision.”

That sentence, “We have nothing left but our vision,” is about those in the EU, in formerly wealthy and, especially, formerly democratic countries, who are now struggling to live. It’s basically asking: what is transparency to someone who has nothing else but seeing the world? So transparency is a state where nothing matters but the visual, if you take it literally.

What does that premium on visuality mean for a graphic designer?

The properties that defined graphic design’s role and function, the “terms of service” of design, are changing. We are no longer always working for the same clients for our entire lives – we cannot be sure that we even have clients. People often think with Metahaven that we’re presenting this lofty idea of graphic design – you should just do your own projects and not care about clients. Actually, it’s the other way around: we are extremely aware of the realities of the contemporary design workplace.

Our views are slightly political, slightly dystopian. Our attempt has always been to create work with people and for people who wouldn’t normally reach out to graphic designers. Historically, graphic design has never been so much about itself. At its better moments, it has tried to create a better relationship with the world. That is something that can no longer be presupposed. You can no longer presuppose that, let’s say, Paul Rand or Steve Jobs will come to you and say, “Hey, can you do a logo for my new computer company?” The circumstances that defined iconic design as an act of mediation, organization, and identity are still important, but they aren’t so much what people are dealing with anymore.

You’ve been addressing issues of mass surveillance for some time, and those who follow such things closely were less surprised by the nature of Edward Snowden’s revelations than their extent. Did those leaks change your practice?

“The faster technology seems to progress, the more difficult it becomes to be critical.”

Very pragmatically, it has made it easier to talk about what we do to a variety of people. Ever since the Snowden revelations there have been all kinds of issues about the political aspects of technology, surveillance, and about the Internet as architecture. Basically, the Internet as something other than a very convenient space has become something that a lot more people started thinking about. Whether it’s really influenced our own practice, it’s hard to say.

Snowden, in a sense, became the new figurehead of black transparency, and that has forced WikiLeaks to take a different position. It has forced WikiLeaks into this role as the kind of godfather of transparency rather than the protagonist, and that might ultimately be a good thing. The fact that a brilliant public speaker like Sarah Harrison has come forward representing Wikileaks is very productive. There’s a number of ways that Snowden works into the larger PR story, but he has brought to light the scale of what’s going on, the way certain programs are named, and has revealed this lexicon of bizarreness.

The first “Captives of the Cloud,” our three-part essay for e-flux journal, was written in September 2012, and the only proof of anything like the Snowden revelations at the time was that someone in 2002 had seen a dedicated NSA ops room in an AT&T data center in San Francisco and had testified to that. There had been two U.S. senators who had been talking about a secret interpretation of the Patriot Act that was used by the administration to allow for large-scale surveillance. Those were the only two factual observations that there were about the NSA’s activities. Then, of course, everyone could see that the NSA was building these enormous data centers and wondered what are these facilities were for. Which brings us back to the physical form of data and networks. When you see those phenomena, and you only see glimpses, it remains mysterious. Now you could say that this whole black world is still bad, but it’s no longer mysterious, because it’s been revealed.

Your continuing “Captives of the Cloud” series in e-flux journal seems to resonate, at least in name, with Rem Koolhaas’s 1972 photomontage thesis project, Exodus, or the Voluntary Prisoners of Architecture. I assume your cloud-captives are also voluntary, wooed by the charms of belonging to the Internet, or “network power,” as you have described it?

Yes. But the type of city that Koolhaas talks about with the Voluntary Prisoners of Architecture is a very different type of city than the one that Pier Vittorio Aureli indicates with the “walled city” or “the project of autonomy.” There’s a difference between the city as a productive machine, or even a sexualized machine, and as the core political unit, a unit of sovereignty. We see both types of thinking. We’ve seen the city as a machine, or productive assemblage, everywhere cities are growing. We see the same where social networks are growing.

Inevitably, the question arises: who is governing? Who is actually in charge? Are we in charge ourselves? Are people capable of making decisions about their own lives? When governance becomes a complete abstraction, how do you regain or reconfigure access to the ways that it is shaped?

This condition is another byproduct of the age of black transparency, that it’s not just about critiquing those in power, but it’s also about how to do it differently. How to create decision-making structures that are better and more finegrained than the every-four-or-five year voting procedure by which we now choose the people who govern us. The Pirate Parties in Europe have some pretty interesting ideas on this. They propose something called “liquid democracy.” There’s a number of issues on which decisions need to be made. You can either vote yourself or you can delegate your vote to someone else. It can become an umbrella for large groups of voters. So it’s like a representative model, but it’s also a direct democracy model, because you can also choose not to delegate. Those decision-making structures are not worked out yet for, say, running countries, but they are working on smaller scales.

Your forthcoming film, City Rising, is shot with a model for New Babylon (by the Dutch artist-architect Constant) in the foreground. How does this megastructure project connect with your work?

“Talking about the present is talking about something that is so strange that you’re already implying the future.”

We always wanted to do something with Constant’s New Babylon, this future city of play, which Mark Wigley called the “hyper-architecture of desire.” So through the Cobra Museum we got the opportunity to work with the original models of New Babylon. Constant worked on this project for about 20 years, and it consists of architectural maquettes, of photographs, of all kinds of visual material. The maquettes are of different “sectors” that would not be located in one place on earth but would be a way of connecting different cities and places together. We filmed the models very close and in front of a green screen, and they end up working as a kind of frame for the film running in the background. We thought: why not create a video where we talk about how New Babylon has been unwittingly realized, not through physical architecture so much, but through the infrastructure of smart phones, social media, etc., and about the way that that works with a transformation of the role of labor, effective labor, immaterial labor, and intimacy? The first part of the video deals with the intimacy aspect of that story and is an edited version of our friend Brian Kuan Wood’s essay on love, which was just published in e-flux, and the second part, which we’re still working on, is dealing a little bit more with the Internet aspect of it, or the networking aspect of it. Basically it’s a way of readdressing New Babylon.

The terms “speculative design” and “critical design” are often used to describe your work. Do you identify with either, and is there a meaningful distinction between the two?

“Speculative design” is a term we are comfortable with using. “Critical design” we are using less. What “critical” means is a discussion in itself. The latest Dunne and Raby book is called Speculative Everything. They are the people who previously also defined critical design, so to some extent, it’s two terms coming out of the same faucet. Both terms try to distinguish a modality of practice that is questioning, or that is different from, let’s say, the “normal” way of practicing, which is compliant – that presupposes design as being something pretty functional and straightforward. So to distinguish other design from that you need words like “critical” and “speculative.” If we take this whole transformation of design as a productive sphere, into immaterial labor, etc. – if we take that transformation seriously, then to some extent, why isn’t everyday design critical design? Why isn’t something on Tumblr speculative design? So in a way those labels lose a little bit of their ability to distinguish one type of practice from another, once the whole practice is under complete transformation.

Dunne and Raby are an admirable studio and incredibly smart. They also emerged out of the Great Britain of the 1990s. That is the time of Blair and Anthony Giddens’s “third way,” when there was a lot of theorizing about how politicians are filters and managers of proposals that come out of the scientific world, out of technology, and there will be a civic debate around how we are going to determine what we want as a people. The purpose of critical design was to make these propositions that would lead to civic debate about our future. It’s analogous to the “third way,” presenting options for rational debate over alternatives. But there are ways for these alternatives to shape and become implemented without that sense of civic debate and without the people being able to do something about it. This potential of critical design has been bypassed, as was the notion of publicness that it hopes to facilitate.

What does the haven represent for you?

Basically, it comes from identifying ourselves with data havens. A haven is of course an island, a sanctuary, a safehouse, a little oasis, a space of exception. The idea is that we’ve run out of them, to some extent, in the current geopolitical and social climate, and that we’re always on the lookout for them. Redefining what an exception is is key to any political project. Thinking from Hakim Bey’s “temporary autonomous zone” to Hardt and Negri’s “Empire” or something like WikiLeaks – it’s always about the same things.

Less and less are we imagining social totalities, utopias as complete futures. Less and less are we able to envision things on that scale. Increasingly, we imagine aspects of reality changing, or we imagine particular pockets in space or time where things are temporarily different. Maybe “haven” is a way of acknowledging the smaller scale of change.

Naming ourselves Metahaven was a way of engaging with topics we came across when working on the Principality of Sealand. Whether it’s about a state or space of exception or other obscure examples that combine anarchy and monarchy, or different forms of state power, the Internet, and the network society – in all these there are questions of design present, and it’s a thread running through our practice.

John Perry Barlow, a founding member of the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), among other things, has called for Iceland to become the “Switzerland of bits.” As Switzerland is less and less the Switzerland of anything, given stricter financial regulations, can havens exist? We know what happened to the Silk Road, and to Sealand –

Poor Sealand! If we want to avoid networks being centrally controlled, then using different softwares, and a variety of tools and networks, or havens, would help avoid it. The haven as a physical location that coincides with its own regime is not going to work, because a network is by definition transnational. Something we’ve seen, and Keller Easterling is the a narrator of this, is the power of standardization over the last decade. With the NSA and GCHQ, and with Snowden, we see the outer limits of standardization. Can you standardize not just the cables, the software that runs on the cables, the routers that people arrive at, and the computers people use, but also the regime that looks into those people?

It’s a question of the possibility of people doing things differently, or the possibility of certain pockets in the network treating things differently, that becomes really critical. The faster technology seems to progress, the more difficult it becomes to be the transgressive or critical node. It’s not as if there was a mass exodus from Facebook after the NSA revelations. We need those social media in order to talk about these things. We need Twitter to talk about monitoring.

Are there any other interesting havens on the geopolitical map?

Well, there’re also “freeports.” Luxembourg is growing immensely as a freeport, which is a place for goods in transit. So you’ve got these massive art warehouses, and the art is in transit, so it’s not taxable. A piece of property in transit is nowhere, literally. Those are havens, too. Those same warehouses also have data storage. There is an idea that if whatever is stored is of extreme value, then you automatically have a haven. But if there’s no value assigned to the thing that’s stored, then you don’t have a haven.

You live and work between Europe and the U.S., and also very much online. Do you think your engagement with the turmoil of EU austerity is taken as prophetic in other settings? How does your address, or reception, change from one audience to another?

Black transparency is probably viewed in the U.S. as a sort of Coming Insurrection-type thing! The fact is, a lot of our inspiration comes from the U.S. In the U.S. there’s a very developed discourse around civil rights, notions that are sometimes taken for granted or forgotten in Europe. There’s also an inherent misperception of design work from Europe in the U.S. Of course there’s a kind of myth-forming about Europe in the States. I feel like we’re breaking with that image of European design, but also perpetuating it because the work that we do is even weirder. I don’t know.

To ask a terribly reductive question: are you more interested in the present or the future?

In trying to describe the present, you already have to speculate – it’s already a form of science fiction. We’re dealing with a situation that is already so absurd that any attempt at talking about it in depth results in some form of speculative fiction. The people who are trying to control the future are in a way more conservative than the people who talk about the present. The failure of cypherpunk science fiction to function properly after WikiLeaks is stunning. People like Bruce Sterling have been almost infuriated over the Snowden and WikiLeaks revelations, and there’s a very pragmatic reason. The Snowden revelations go further than cypherpunk predictions, and Sterling even said the people in the NSA are his readers. In other words, cypherpunk fiction also needed to be believed by governments. Michael Froomkin makes this point. He talks about the fact that the utopian, anarchic Internet may never have even been realized, but the threat of it was believed by governments before it was realized. So talking about the present is talking about something that is so strange that you’re already implying the future. We’re actually talking about the present.

Credits

- Text: ROBERT WIESENBERGER