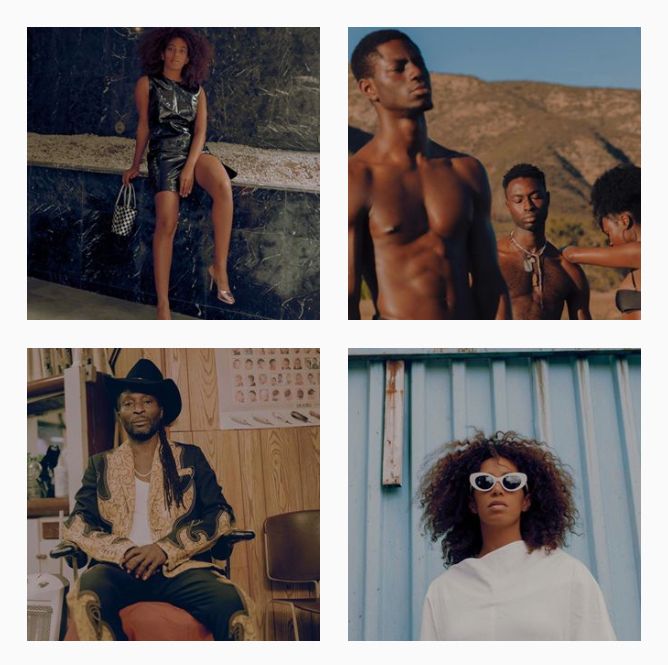

Man in the Mirror: MICAIAH CARTER for RALPH LAUREN

|OMB

Micaiah Carter has photographed everyone. Since last summer alone, his photographs have graced the covers of GQ, Marie Claire, and Wonderland, and count Megan Thee Stallion, Pharrell Williams, Tilda Swinton, and Tiraji P. Henson, among many more, as their subjects. This year marks half a century since the first Christopher Street Liberation Day March – the blueprint for today’s LGBTQIA+ Pride celebrations – took place on the first anniversary of the Stonewall uprisings in New York. In homage, Ralph Lauren launches We Stand Together, a global campaign that aims to “send a message of solidarity to the world.” While marches in Berlin and around Europe continues into July, America’s Pride month, June, was reduced to more intimate revelries by the still-raging pandemic. Starring alongside Pose heartthrob, Indya Moore and HOLLYWOOD darling, Jeremy Pope, is 25-year-old Carter, who produced a series of quarantined self-portraits from his Brooklyn rooftop for the RL collaboration.

I read elsewhere that your father’s photo albums were early sources of inspiration for you. Did the styles in those albums make an impression on you growing up? Have you always been interested in fashion?

Those images, a lot of them were taken in the late 1970s when my dad was in his twenties. There’s a plethora of different styles and different types of people that he photographed. I loved it a lot because each person has their own character, their own style and their own individuality, which I really respected. It’s been an off-and-on thing for me, personally. I’m always interested in fashion for my work, but this is probably the first time where I felt really connected to the pieces. Because they’re simple, but they also meant a lot for the meaning behind the clothing.

Speaking of, how did this collaboration with Ralph Lauren come about?

They reached out to me, actually, about the new Pride campaign.

What was the experience like, being in front of the camera rather than behind it? Did your surroundings dictate the setting and composition, or were there additional factors that influenced the images you took?

It was an interesting exploration for me. Being at my apartment was a challenge. During COVID, we weren’t able to have sets like we used to, so it was nice to get a chance to turn the camera on myself for once. This was probably my first time being really direct with myself in front of the camera, but I definitely want to do more.

In your experience, how is the practice of photography linked to LGBTQIA+ liberation?

I feel like it’s about visibility, making sure there’s inclusion in an honest and straightforward way that’s not deceptive or just checking a box. Really being precise and intimate about how people are captured, showing their true selves in relation to the world.

What are your thoughts on the role of photography as it relates to resistance more broadly? There has been a lot of discourse in the last weeks about images, both as something that we rely on as a record of supposed fact, and also, rightfully, a source of skepticism. Especially around the recent protests, discussion of the politics of blurring protesters' faces has come to the fore, which I think gets into a whole conversation around people, rights, ownership, autonomy and validity. What is your perspective on these conversations?

I think it’s important to document what’s going on, not as a tool to regulate and to divide, but just as a truth teller. I think photography is able to do that and not erase Black history. Especially now with so much change going on with democracy, trans rights – in general, I think it’s so important to have these photographs and photograph these people, not only in this documentary setting, but also in the portraits that Black photographers are taking for Time and New York Time magazine. It is so important for this time.

Do you shoot primarily on film or digitally, and what’s your relationship to each? What does one afford your practice that the other doesn’t?

I like shooting film more. I used to shoot a lot of digital, but film helps me slow down, and I really enjoy how it’s not digital. You can do analog things that you can’t replicate digitally. I think being able to see the images, being able to preview them, see what’s going on, what you can fix. I think it’s necessary when you’re with clients, so everyone’s on the same page about what you’re doing. Another advantage is probably just that it’s quicker than film, because film takes a whole process.

I was first introduced to your work through the internet, so I’ve most often seen it mediated through a screen. How has social media impacted the way that we understand or relate to images? Was defining a photographic style and developing your practice was more, or less difficult in the age of Instagram?

It gives a chance for visibility, more than anything. And this gives a chance for people to share on their own platforms, versus needing a platform in order to share. While I was developing my practice, Instagram was not what it was today. It was just iPhone pictures. Tumblr was still a big influx of photographers posting their work there, so I got a mixture of being on Tumblr first, and then going to Instagram. Before Instagram, you had to really show your portfolio to certain people but with Instagram, you’re able to show your portfolio to the world, and have discussions with your work out there.

Throughout your body of work, the colors feel really restrained. It almost feels as though they’ve been sepia-toned, but in a more muted hue. One of the things that I’ve thought about a lot is how early film emulsions were never designed to really capture darker skin. So the technique of yours is a really subtle way of inverting that history, or of making images of Black people that are considered, and seek to not just stick them into a campaign, but rather to make the image conform to the individual. How did this practice develop?

Exactly. That developed in my toning and coloring when I was shooting a lot of digital, because I wanted that film look, and then I just kept it when I moved on to shooting film. I tend to desaturate everything, but then bring up the colors, which… it’s a weird process. But by doing that, I think it flattens the image a little bit to make it feel like a painting, but then also using those sepia tones really brings out the color in the skin and makes that the highlight, while still retaining all the color to make it all feel like it’s one image.

Credits

- All Photography: Micaiah Carter

- Text: OMB