How Nightclub Design Cured Modernism’s Hangover

|Philip Maughan

Nightclubs are improvised zones of creative excess, inseparable from the styles and technologies that define them. Since emerging as an offshoot of the multifunctional leisure complexes of the 1960s, when the French words for “disc” and “library” combined to give us discothèque, signaling a shift away from live toward recorded music, clubs have been laboratories for design practices of every kind: clothing, visual marketing, make-up, furniture, and light. Nightclubs encourage experimentation precisely because they are experiments themselves. As a totality, they form a cultural counter-history, an architecture that reveals nothing to those who are not invited. Their story belongs exclusively to the night.

“Time stops here and space takes over,” Andy Warhol said about Studio 54, a phrase that could serve as the mantra for Night Fever: Designing Club Culture 1960–Today. The exhibition at Vitra Design Museum takes an encyclopedic look at the disco-as-design engine, and its accompanying catalogue reads like a list of 032c pet fascinations, sprawling across Italy’s Radical Design Nightclubs (Issue 30), Ettore Sottsass (Issue 27), Cedric Price (Issue 2 and 32), Area (Issue 26), Bunker (Issue 24), and beyond.

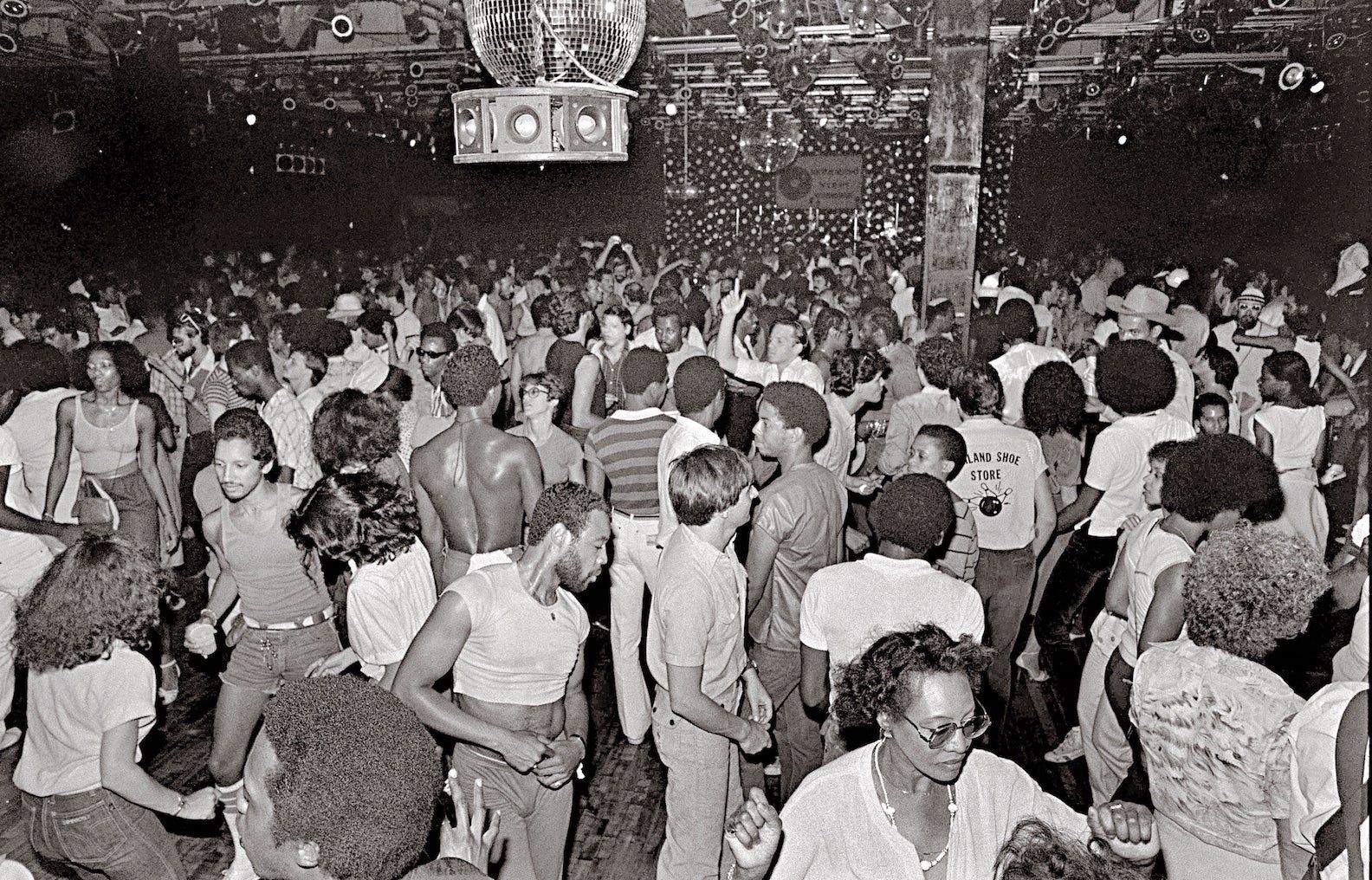

The spaces featured here are architectural fever dreams whose constituent parts are indexed for the purposes of both study and historical FOMO: dancefloor blueprints, furniture brochures, magazine spreads, membership cards, and long-demolished wall art. New York’s Area produced invitations to fit its repertory of themed parties: a “natural history” invite on the inside of an egg shell, or a “suburbia” invite stamped on a slice of Velveeta cheese. The combination of art deco ziggurats, exposed TV studio equipment, and a nose-candy-proffering Man in the Moon at Studio 54 “was the lynchpin of the club’s success,” says cofounder Ian Schrager. “Design played a big role, because the club wasn’t just painted black and wasn’t so dark you didn’t notice anything; there was some style and sophistication to it.”

There are multiple instances of overlap between club culture and the catwalk, a symbiotic relationship that is singularly difficult to trace through time, dealing as it does with the bratty and forgetful spheres of underground music and fashion. At Belgian hotspots like Boccaccio and Mirano Continental, a young Raf Simons and the Antwerp Six spent frenzied nights jamming to a slowed EBM groove known as New Beat. After a long period of dormition, the profusion of new clubs inspired revelers to don blouses, Doc Martens, and blazers patched with religious prints and safety pins. The record label Antler-Subway produced a number of New Beat-themed apparel collections, advertised on its record sleeves, while the Continental’s artistic director, Etienne Russo, would later create runway shows for Dries van Noten.

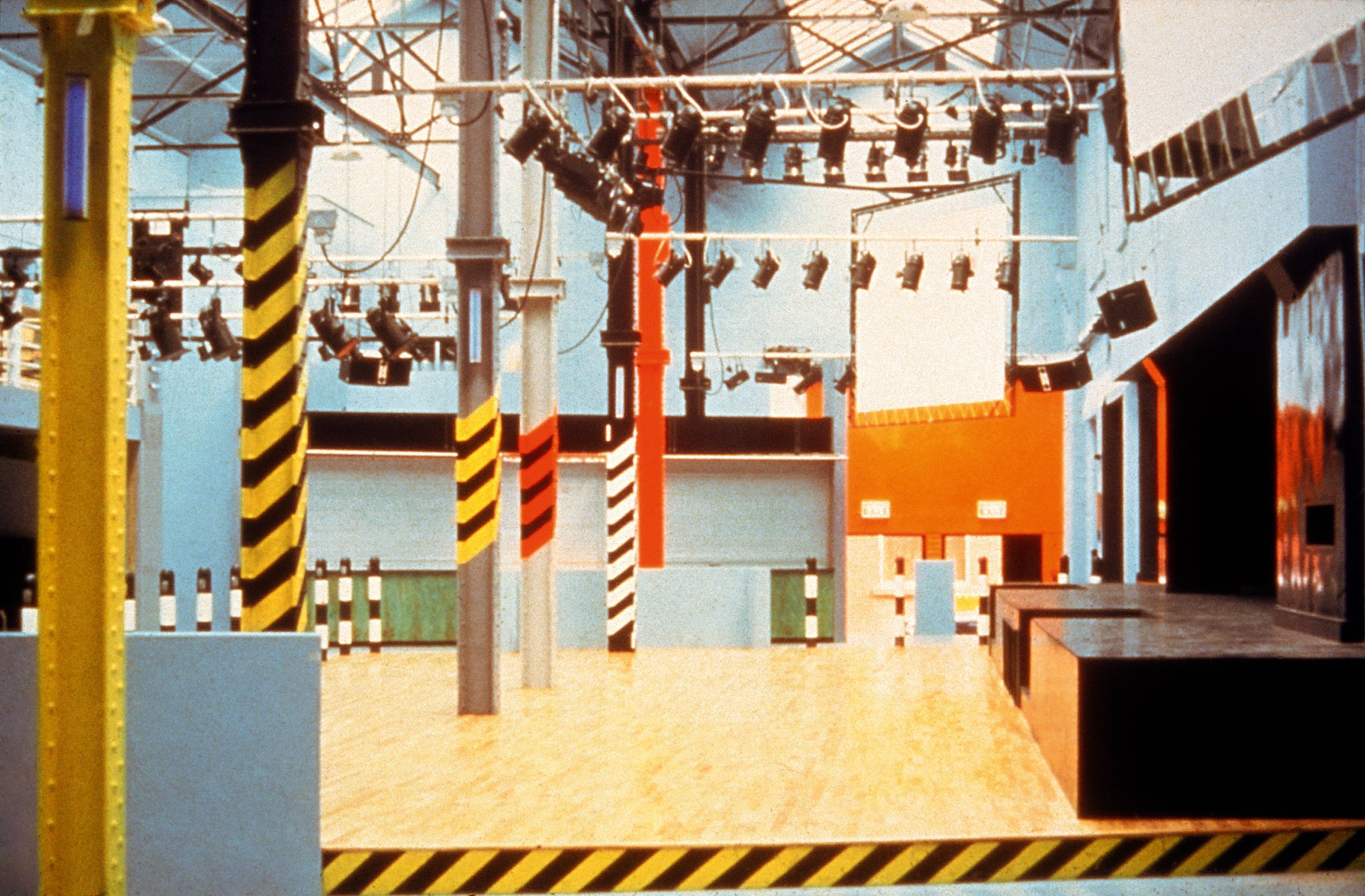

In the earliest days of the discotheque, clubs were a tabula rasa for the PVC expressionists of Italy’s radical design movement. Committed to ephemerality, they unraveled the stern maxims of late Modernism. First was The Piper, opened in Rome in 1965 after a modest commission from a globe-trotting lawyer who dreamed of owning “a giant pinball machine for youngsters.” Architect Francesco Capolei used “wood and bricks all painted white, rubber cladding, and Perspex with lights inside” in an attempt to build cheaply. Throughout their history, club owners have striven to build alternate realities with limited means. The visual language that enveloped Manchester’s Haçienda – a collection of roadside bollards, red-and-black-striped warning tape, and cat’s eyes set in concrete – initially emerged for practical reasons. The dance floor in the former yacht salesroom was littered with physical hazards. The concept, imagined by interior designer Ben Kelly, would later become another sort of warning. In 2004, it was transferred to the British fitness chain Gymbox, whose corporate identity Kelly also designed. As healthy living, sobriety, and digitally-induced idleness lure the young away, nightclubs struggle to define their role. Then there is the ubiquitous problem of escalating rent. As an advert for the luxury apartments that eventually replaced the Haçienda put it: “Now the party’s over … you can go home.”

Night Fever: Designing Club Culture 1960–Today is published by Vitra Design Museum (Weil am Rhein, 2018).

Credits

- Text: Philip Maughan